Electronvolt

In physics, an electronvolt (symbol eV, also written electron-volt and electron volt) is the measure of an amount of kinetic energy gained by a single electron accelerating from rest through an electric potential difference of one volt in vacuum. When used as a unit of energy, the numerical value of 1 eV in joules (symbol J) is equivalent to the numerical value of the charge of an electron in coulombs (symbol C). Under the 2019 redefinition of the SI base units, this sets 1 eV equal to the exact value 1.602176634×10−19 J.[1]

Historically, the electronvolt was devised as a standard unit of measure through its usefulness in electrostatic particle accelerator sciences, because a particle with electric charge q gains an energy E = qV after passing through a voltage of V. Since q must be an integer multiple of the elementary charge e for any isolated particle, the gained energy in units of electronvolts conveniently equals that integer times the voltage.

It is a common unit of energy within physics, widely used in solid state, atomic, nuclear, and particle physics, and high-energy astrophysics. It is commonly used with SI prefixes milli-, kilo-, mega-, giga-, tera-, peta- or exa- (meV, keV, MeV, GeV, TeV, PeV and EeV respectively). In some older documents, and in the name Bevatron, the symbol BeV is used, which stands for billion (109) electronvolts; it is equivalent to the GeV.

Definition

An electronvolt is the amount of kinetic energy gained or lost by a single electron accelerating from rest through an electric potential difference of one volt in vacuum. Hence, it has a value of one volt, 1 J/C, multiplied by the elementary charge e = 1.602176634×10−19 C.[2] Therefore, one electronvolt is equal to 1.602176634×10−19 J.[1]

The electronvolt (eV) is a unit of energy, but is not an SI unit. The SI unit of energy is the joule (J).

Relation to other physical properties and units

| Measurement | Unit | SI value of unit |

|---|---|---|

| Energy | eV | 1.602176634×10−19 J |

| Mass | eV/c2 | 1.78266192×10−36 kg |

| Momentum | eV/c | 5.34428599×10−28 kg·m/s |

| Temperature | eV/kB | 1.160451812×104 K |

| Time | ħ/eV | 6.582119×10−16 s |

| Distance | ħc/eV | 1.97327×10−7 m |

Mass

By mass–energy equivalence, the electronvolt corresponds to a unit of mass. It is common in particle physics, where units of mass and energy are often interchanged, to express mass in units of eV/c2, where c is the speed of light in vacuum (from E = mc2). It is common to informally express mass in terms of eV as a unit of mass, effectively using a system of natural units with c set to 1.[3] The kilogram equivalent of 1 eV/c2 is:

For example, an electron and a positron, each with a mass of 0.511 MeV/c2, can annihilate to yield 1.022 MeV of energy. A proton has a mass of 0.938 GeV/c2. In general, the masses of all hadrons are of the order of 1 GeV/c2, which makes the GeV/c2 a convenient unit of mass for particle physics:[4]

The atomic mass constant (mu), one twelfth of the mass a carbon-12 atom, is close to the mass of a proton. To convert to electronvolt mass-equivalent, use the formula:

Momentum

By dividing a particle's kinetic energy in electronvolts by the fundamental constant c (the speed of light), one can describe the particle's momentum in units of eV/c.[5] In natural units in which the fundamental velocity constant c is numerically 1, the c may informally be omitted to express momentum as electronvolts.

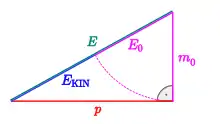

in natural units (with )

is a Pythagorean equation. When a relatively high energy is applied to a particle with relatively low rest mass, it can be approximated as in high-energy physics such that an applied energy in units of eV conveniently results in an approximately equivalent change of momentum in units of eV/c.

The dimensions of momentum units are T−1LM. The dimensions of energy units are T−2L2M. Dividing the units of energy (such as eV) by a fundamental constant (such as the speed of light) that has units of velocity (T−1L) facilitates the required conversion for using energy units to describe momentum.

For example, if the momentum p of an electron is said to be 1 GeV, then the conversion to MKS system of units can be achieved by:

Distance

In particle physics, a system of natural units in which the speed of light in vacuum c and the reduced Planck constant ħ are dimensionless and equal to unity is widely used: c = ħ = 1. In these units, both distances and times are expressed in inverse energy units (while energy and mass are expressed in the same units, see mass–energy equivalence). In particular, particle scattering lengths are often presented in units of inverse particle masses.

Outside this system of units, the conversion factors between electronvolt, second, and nanometer are the following:

The above relations also allow expressing the mean lifetime τ of an unstable particle (in seconds) in terms of its decay width Γ (in eV) via Γ = ħ/τ. For example, the

B0

meson has a lifetime of 1.530(9) picoseconds, mean decay length is cτ = 459.7 μm, or a decay width of (4.302±25)×10−4 eV.

Conversely, the tiny meson mass differences responsible for meson oscillations are often expressed in the more convenient inverse picoseconds.

Energy in electronvolts is sometimes expressed through the wavelength of light with photons of the same energy:

Temperature

In certain fields, such as plasma physics, it is convenient to use the electronvolt to express temperature. The electronvolt is divided by the Boltzmann constant to convert to the Kelvin scale:

where kB is the Boltzmann constant.

The kB is assumed when using the electronvolt to express temperature, for example, a typical magnetic confinement fusion plasma is 15 keV (kiloelectronvolt), which is equal to 174 MK (megakelvin).

As an approximation: kBT is about 0.025 eV (≈ 290 K/11604 K/eV) at a temperature of 20 °C.

Wavelength

The energy E, frequency v, and wavelength λ of a photon are related by

where h is the Planck constant, c is the speed of light. This reduces to[6]

A photon with a wavelength of 532 nm (green light) would have an energy of approximately 2.33 eV. Similarly, 1 eV would correspond to an infrared photon of wavelength 1240 nm or frequency 241.8 THz.

Scattering experiments

In a low-energy nuclear scattering experiment, it is conventional to refer to the nuclear recoil energy in units of eVr, keVr, etc. This distinguishes the nuclear recoil energy from the "electron equivalent" recoil energy (eVee, keVee, etc.) measured by scintillation light. For example, the yield of a phototube is measured in phe/keVee (photoelectrons per keV electron-equivalent energy). The relationship between eV, eVr, and eVee depends on the medium the scattering takes place in, and must be established empirically for each material.

Energy comparisons

| γ: Gamma rays | MIR: Mid infrared | HF: High freq. |

| HX: Hard X-rays | FIR: Far infrared | MF: Medium freq. |

| SX: Soft X-rays | Radio waves | LF: Low freq. |

| EUV: Extreme ultraviolet | EHF: Extremely high freq. | VLF: Very low freq. |

| NUV: Near ultraviolet | SHF: Super high freq. | VF/ULF: Voice freq. |

| Visible light | UHF: Ultra high freq. | SLF: Super low freq. |

| NIR: Near Infrared | VHF: Very high freq. | ELF: Extremely low freq. |

| Freq: Frequency |

| Energy | Source |

|---|---|

| 5.25×1032 eV | total energy released from a 20 kt nuclear fission device |

| 12.2 ReV (1.22×1028 eV) | the Planck energy |

| 10 YeV (1×1025 eV) | approximate grand unification energy |

| ~624 EeV (6.24×1020 eV) | energy consumed by a single 100-watt light bulb in one second (100 W = 100 J/s ≈ 6.24×1020 eV/s) |

| 300 EeV (3×1020 eV = ~50 J) | The first ultra-high-energy cosmic ray particle observed, the so-called Oh-My-God particle.[10] |

| 2 PeV | two petaelectronvolts, the highest-energy neutrino detected by the IceCube neutrino telescope in Antarctica[11] |

| 14 TeV | designed proton center-of-mass collision energy at the Large Hadron Collider (operated at 3.5 TeV since its start on 30 March 2010, reached 13 TeV in May 2015) |

| 1 TeV | a trillion electronvolts, or 1.602×10−7 J, about the kinetic energy of a flying mosquito[12] |

| 172 GeV | rest energy of top quark, the heaviest measured elementary particle |

| 125.1±0.2 GeV | energy corresponding to the mass of the Higgs boson, as measured by two separate detectors at the LHC to a certainty better than 5 sigma[13] |

| 210 MeV | average energy released in fission of one Pu-239 atom |

| 200 MeV | approximate average energy released in nuclear fission fission fragments of one U-235 atom. |

| 105.7 MeV | rest energy of a muon |

| 17.6 MeV | average energy released in the nuclear fusion of deuterium and tritium to form He-4; this is 0.41 PJ per kilogram of product produced |

| 2 MeV | approximate average energy released in a nuclear fission neutron released from one U-235 atom. |

| 1.9 MeV | rest energy of up quark, the lowest mass quark. |

| 1 MeV (1.602×10−13 J) | about twice the rest energy of an electron |

| 1 to 10 keV | approximate thermal temperature, , in nuclear fusion systems, like the core of the sun, magnetically confined plasma, inertial confinement and nuclear weapons |

| 13.6 eV | the energy required to ionize atomic hydrogen; molecular bond energies are on the order of 1 eV to 10 eV per bond |

| 1.6 eV to 3.4 eV | the photon energy of visible light |

| 1.1 eV | energy required to break a covalent bond in silicon |

| 720 meV | energy required to break a covalent bond in germanium |

| < 120 meV | approximate rest energy of neutrinos (sum of 3 flavors)[14] |

| 25 meV | thermal energy, , at room temperature; one air molecule has an average kinetic energy 38 meV |

| 230 μeV | thermal energy, , of the cosmic microwave background |

Per mole

One mole of particles given 1 eV of energy each has approximately 96.5 kJ of energy – this corresponds to the Faraday constant (F ≈ 96485 C⋅mol−1), where the energy in joules of n moles of particles each with energy E eV is equal to E·F·n.

See also

References

- "2018 CODATA Value: electron volt". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. 20 May 2019. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- "2018 CODATA Value: elementary charge". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. 20 May 2019. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- Barrow, J. D. (1983). "Natural Units Before Planck". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 24: 24. Bibcode:1983QJRAS..24...24B.

- Gron Tudor Jones. "Energy and momentum units in particle physics" (PDF). Indico.cern.ch. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- "Units in particle physics". Associate Teacher Institute Toolkit. Fermilab. 22 March 2002. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- "CODATA Value: Planck constant in eV s". Archived from the original on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- What is Light? Archived December 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine – UC Davis lecture slides

- Elert, Glenn. "Electromagnetic Spectrum, The Physics Hypertextbook". hypertextbook.com. Archived from the original on 2016-07-29. Retrieved 2016-07-30.

- "Definition of frequency bands on". Vlf.it. Archived from the original on 2010-04-30. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- Open Questions in Physics. Archived 2014-08-08 at the Wayback Machine German Electron-Synchrotron. A Research Centre of the Helmholtz Association. Updated March 2006 by JCB. Original by John Baez.

- "A growing astrophysical neutrino signal in IceCube now features a 2-PeV neutrino". 21 May 2014. Archived from the original on 2015-03-19.

- Glossary Archived 2014-09-15 at the Wayback Machine - CMS Collaboration, CERN

- ATLAS; CMS (26 March 2015). "Combined Measurement of the Higgs Boson Mass in pp Collisions at √s=7 and 8 TeV with the ATLAS and CMS Experiments". Physical Review Letters. 114 (19): 191803. arXiv:1503.07589. Bibcode:2015PhRvL.114s1803A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.191803. PMID 26024162.

- Mertens, Susanne (2016). "Direct neutrino mass experiments". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 718 (2): 022013. arXiv:1605.01579. Bibcode:2016JPhCS.718b2013M. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/718/2/022013. S2CID 56355240.