Rubella vaccine

Rubella vaccine is a vaccine used to prevent rubella.[1][2] Effectiveness begins about two weeks after a single dose and around 95% of people become immune. Countries with high rates of immunization no longer see cases of rubella or congenital rubella syndrome. When there is a low level of childhood immunization in a population it is possible for rates of congenital rubella to increase as more women make it to child-bearing age without either vaccination or exposure to the disease. Therefore, it is important for more than 80% of people to be vaccinated.[1] By introducing rubella containing vaccines, rubella has been eradicated in 81 nations, as of mid-2020.[3]

MMR vaccine contains rubella vaccine | |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target | Rubella |

| Vaccine type | Attenuated |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Meruvax, other |

| MedlinePlus | a601176 |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| | |

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that the rubella vaccine be included in routine vaccinations. If not all people are immunized then at least women of childbearing age should be immunized. It should not be given to those who are pregnant or those with very poor immune function. While one dose is often all that is required for lifelong protection, often two doses are given.[1]

Side effects are generally mild. They may include fever, rash, and pain and redness at the site of injection. Joint pain may be reported at between one and three weeks following vaccination in women. Severe allergies are rare. The rubella vaccine is a live attenuated vaccine. It is available either by itself or in combination with other vaccines. Combinations include with measles (MR vaccine), measles and mumps vaccine (MMR vaccine) and measles, mumps and varicella vaccine (MMRV vaccine).[1]

A rubella vaccine was first licensed in 1969.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[5][6] As of 2019, more than 173 countries included it in their routine vaccinations.[1]

Medical uses

Rubella vaccine is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[5][6]

Schedule

There are two main ways to deliver the rubella vaccine. The first is initially efforts to immunize all people less than forty years old followed by providing a first dose of vaccine between 9 and 12 months of age. Otherwise simply women of childbearing age can be vaccinated.[1]

While only one dose is necessary two doses are often given as it usually comes mixed with the measles vaccine.[1]

Pregnancy

Women who are planning to become pregnant are recommended to have rubella immunity beforehand, as the virus has a potential to cause miscarriage or serious birth defects.[7] Immunity may be verified by pre-pregnancy blood test, and it is recommended that those with negative results should refrain from getting pregnant for at least a month after receiving the vaccine.[7]

The vaccine theoretically should not be given during pregnancy. However, more than a thousand women have been given the vaccine when they did not realize that they were pregnant and no negative outcomes occurred. Testing for pregnancy before giving the vaccine is not needed.[1]

If a low titre is found during pregnancy, the vaccine should be given after delivery. It is also advisable to avoid becoming pregnant for the four weeks following the administration of the vaccine.[8]

History

Since the rubella epidemics that swept Europe in 1962-1963 and the US in 1964–1965, several efforts were made to develop effective vaccines using attenuated viral strains, both in US and abroad.[9]

HPV-77

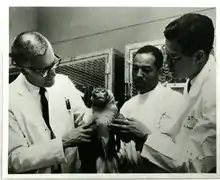

The first successful strain to be used was the HPV-77, prepared by passing the virus through the cells of an African green monkey kidney 77 times. The efforts to develop the vaccine were conducted by a team of researchers at the National Institutes of Health's Division of Biologics Standards. Lead by Harry M. Meyer and Paul J. Parkman, the team included Hope E. Hopps,[10] Ruth L. Kirschstein, and Rudyard Wallace among others, the team began serious work on the vaccine with the arrival of a major rubella epidemic in the United States in 1964. Prior to arriving at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Parkman had been working on isolating the rubella virus for the Army. He joined the laboratory of Harry Meyer.[11]

Parkman, Meyer, and the team from the NIH tested the vaccine at the Children's Colony in Conway, Arkansas in 1965 while a rubella epidemic still raged across the United States.[12] This residential home provided care for children with cognitive disabilities and children who were ill. The ability to isolate children in their cabins and control access to the children made it an ideal location for testing a vaccine without starting an epidemic of rubella. Each of the children's parents provided consent for the participation in the trial.[11]

In June 1969, the NIH issued the first license for commercial production of the rubella vaccine to the pharmaceutical company Merck Sharp & Dohme.[13] This vaccine made use of the HPV77 rubella strain and was produced in duck embryo cells. This version of the rubella vaccine was in use for only a few years before the introduction of the combined measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine in 1971.[14]

RA 27/3

Most of the modern Rubella vaccines (including the combination vaccine MMR) contain the RA 27/3 strain,[15] which was developed by Stanley Plotkin and Leonard Hayflick at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia. The vaccine was attenuated and prepared in the WI-38 normal human diploid cell strain which was developed by Hayflick[16][17] and gifted to Plotkin by him.

In order to isolate the virus, instead of taking swab samples from the throats of infected patients, which could have been contaminated with other resident viruses, Plotkin decided to utilize aborted fetuses provided by the department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. At the time, abortion was illegal in most of the United States (including Pennsylvania), but doctors were allowed to perform "therapeutic abortions" when the life of the woman was in danger. Some started to perform them also on women infected with rubella.[18] Several dozens of aborted fetuses were collected and studied by Plotkin. The kidney tissue from fetus 27 produced the strain that was used to develop the attenuated rubella vaccine. The name RA 27/3 refers to "Rubella Abortus", 27th fetus, 3rd organ to be harvested (the kidney).[19]

The vaccine was first approved by the UK in 1970. The strain became the preferred vaccine used by pharmaceutical companies over the HPV-77, due to several considerations, including its higher immunogenicity; Merck made it its mainstay rubella vaccine in 1979.[9]

Types

Rubella is seldom given as an individual vaccine and is often given in combination with measles, mumps, or varicella (chickenpox) vaccines.[20][21] Below is the list of measles-containing vaccines:

- Rubella vaccine (standalone vaccine)

- Measles and rubella combined vaccine (MR vaccine)

- Measles, mumps and rubella combined vaccine (MMR vaccine)[22][23][24]

- Measles, mumps, rubella and varicella combined vaccine (MMRV vaccine).[25] The measles vaccine is equally effective for preventing measles in all formulations, but side effects vary depending with the combination.[20]

References

- World Health Organization (July 2020). "Rubella vaccines : WHO position paper". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 95 (27): 306–24. hdl:10665/332952.

- "Rubella vaccines: WHO position paper – July 2020 – Note de synthèse: position de l'OMS concernant les vaccins antirubéoleux". Weekly Epidemiological Record. World Health Organization. 95 (27): 306–324. 3 July 2020. hdl:10665/332952.

- Suryadevara M (2020). "27. Rubella". In Domachowske J, Suryadevara M (eds.). Vaccines: A Clinical Overview and Practical Guide. Switzerland: Springer. pp. 323–332. ISBN 978-3-030-58413-9.

- Lanzieri T, Haber P, Icenogle JP, Patel M (2021). "Rubella". In Wodi AP, Hamborsky J, Morelli V, Schillie S (eds.). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (14th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- "Pregnancy and Vaccination". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 21 August 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- Marin M, Güris D, Chaves SS, Schmid S, Seward JF, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (June 2007). "Prevention of varicella: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)" (PDF). MMWR Recomm Rep. 56 (RR-4): 1–40. PMID 17585291. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 February 2020.

- Parkman PD (June 1999). "Making vaccination policy: the experience with rubella". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 28 (Suppl 2): S140-6. doi:10.1086/515062. JSTOR 4481910. PMID 10447033.

- Bowen A (6 September 2018). "Finding Hope: A Woman's Place is in the Lab". Circulating Now from NLM. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- Parkman PD. "Dr. Paul Parkman Oral History" (PDF). Office of NIH History. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Milford L. "Arkansas Children's Colony aka: Conway Human Development Center". Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Wendt D (30 September 2015). "Combating infectious disease and slaying the rubella dragon, 1969-1972". O Say Can You See?. National Museum of American History. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- "Rubella". historyofvaccine.org. 7 February 2019. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- "Information Sheet Observed Rate of Vaccine Reactions Measles, Mumps and Rubella Vaccines" (PDF). WHO. May 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- Hayflick L, Moorhead PS (December 1961). "The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains". Experimental Cell Research. 25 (3): 585–621. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. PMID 13905658.

- Hayflick L (March 1965). "The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains". Experimental Cell Research. 37 (3): 614–636. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(65)90211-9. PMID 14315085.

- Little B (5 February 2016). "Way Before Zika, Rubella Changed Minds on Abortion". National Geographic.

- Wadman M (7 February 2017). The Vaccine Race: Science, Politics, and the Human Costs of Defeating Disease. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-698-17778-9.

- World Health Organization (April 2017). "Measles vaccines: WHO position paper – April 2017". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 92 (17): 205–27. hdl:10665/255377. PMID 28459148.

- "Summary of the WHO position on Measles Vaccine- April 2017" (PDF). who.int. 13 September 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2022.

- "M-M-R II- measles, mumps, and rubella virus vaccine live injection, powder, lyophilized, for suspension". DailyMed. 24 September 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- "M-M-RVaxPro EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- "Priorix - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 14 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- "ProQuad- measles, mumps, rubella and varicella virus vaccine live injection, powder, lyophilized, for suspension". DailyMed. 26 September 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

Further reading

- Hall E, Wodi AP, Hamborsky J, Morelli V, Schillie S, eds. (2021). "Chapter 20: Rubella". Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (14th ed.). Washington D.C.: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

External links

- Rubella virus vaccine on MedicineNet

- Rubella on vaccines.gov

- Rubella Vaccine at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)