Franz Mesmer

Franz Anton Mesmer (/ˈmɛzmər/;[1] German: [ˈmɛsmɐ]; 23 May 1734 – 5 March 1815) was a German physician with an interest in astronomy. He theorised the existence of a natural energy transference occurring between all animated and inanimate objects; this he called "animal magnetism", sometimes later referred to as mesmerism. Mesmer's theory attracted a wide following between about 1780 and 1850, and continued to have some influence until the end of the 19th century.[2] In 1843, the Scottish doctor James Braid proposed the term "hypnotism" for a technique derived from animal magnetism; today the word "mesmerism" generally functions as a synonym of "hypnosis". Mesmer also supported the arts, specifically music; he was on friendly terms with Haydn and Mozart.

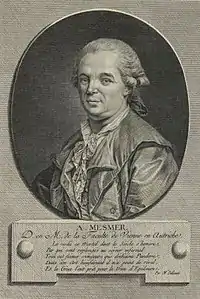

Franz Mesmer | |

|---|---|

Print of Franz Anton Mesmer (Musée de la Révolution française) | |

| Born | Franz Anton Mesmer 23 May 1734 Iznang, Bishopric of Constance |

| Died | 5 March 1815 (aged 80) |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Known for | Animal magnetism |

Early life

Mesmer was born in the village of Iznang (now part of the municipality of Moos), on the shore of Lake Constance in Swabia. He was a son of master forester Anton Mesmer (1701—after 1747) and his wife, Maria Ursula (née Michel; 1701–1770).[3] After studying at the Jesuit universities of Dillingen and Ingolstadt, he took up the study of medicine at the University of Vienna in 1759. In 1766 he published a doctoral dissertation with the Latin title De planetarum influxu in corpus humanum (On the Influence of the Planets on the Human Body), which discussed the influence of the moon and the planets on the human body and on disease. This was not medical astrology.

Building largely on Isaac Newton's theory of the tides, Mesmer expounded on certain tides in the human body that might be accounted for by the movements of the sun and moon.[4] Evidence assembled by Frank A. Pattie suggests that Mesmer plagiarized[5] most of his dissertation from other works,[6][7] including De imperio solis ac lunae in corpora humana et morbius inde oriundis (1704) by Richard Mead, an eminent English physician and Newton's friend. However, in Mesmer's day doctoral theses were not expected to be original.[8]

In January 1768, Mesmer married Anna Maria von Posch, a wealthy widow, and established himself as a doctor in Vienna. In the summers he lived on a splendid estate and became a patron of the arts. In 1768, when court intrigue prevented the performance of La finta semplice (K. 51), for which the twelve-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart had composed 500 pages of music, Mesmer is said to have arranged a performance in his garden of Mozart's Bastien und Bastienne (K. 50), a one-act opera,[9] though Mozart's biographer Nissen found no proof that this performance actually took place. Mozart later immortalized his former patron by including a comedic reference to Mesmer in his opera Così fan tutte.[10]

Animal magnetism

| Hypnosis |

|---|

In 1774, Mesmer produced an "artificial tide" in a patient, Francisca Österlin, who suffered from hysteria, by having her swallow a preparation containing iron and then attaching magnets to various parts of her body. She reported feeling streams of a mysterious fluid running through her body and was relieved of her symptoms for several hours. Mesmer did not believe that the magnets had achieved the cure on their own. He felt that he had contributed animal magnetism, which had accumulated in his work, to her. He soon stopped using magnets as a part of his treatment.

In the same year Mesmer collaborated with Maximilian Hell.

In 1775, Mesmer was invited to give his opinion before the Munich Academy of Sciences on the exorcisms carried out by Johann Joseph Gassner (Gaßner), a priest and healer who grew up in Vorarlberg, Austria. Mesmer said that while Gassner was sincere in his beliefs, his cures resulted because he possessed a high degree of animal magnetism. This confrontation between Mesmer's secular ideas and Gassner's religious beliefs marked the end of Gassner's career as well as, according to Henri Ellenberger, the emergence of dynamic psychiatry.

The scandal that followed Mesmer's only partial success in curing the blindness of an 18-year-old musician, Maria Theresia Paradis, led him to leave Vienna in 1777. In February 1778 Mesmer moved to Paris, rented an apartment in a part of the city preferred by the wealthy and powerful, and established a medical practice. There he would reunite with Mozart who often visited him. Paris soon divided into those who thought he was a charlatan who had been forced to flee from Vienna and those who thought he had made a great discovery.

In his first years in Paris, Mesmer tried and failed to get either the Royal Academy of Sciences or the Royal Society of Medicine to provide official approval for his doctrines. He found only one physician of high professional and social standing, Charles d'Eslon, to become a disciple. In 1779, with d'Eslon's encouragement, Mesmer wrote an 88-page book, Mémoire sur la découverte du magnétisme animal, to which he appended his famous 27 Propositions. These propositions outlined his theory at that time. Some contemporary scholars equate Mesmer's animal magnetism with the Qi (chi) of Traditional Chinese Medicine and mesmerism with medical Qigong practices.[11][12]

According to d'Eslon, Mesmer understood health as the free flow of the process of life through thousands of channels in our bodies. Illness was caused by obstacles to this flow. Overcoming these obstacles and restoring flow produced crises, which restored health. When Nature failed to do this spontaneously, contact with a conductor of animal magnetism was a necessary and sufficient remedy. Mesmer aimed to aid or provoke the efforts of Nature. To cure an insane person, for example, involved causing a fit of madness. The advantage of magnetism involved accelerating such crises without danger.

Procedure

Mesmer treated patients both individually and in groups. With individuals he would sit in front of his patient with his knees touching the patient's knees, pressing the patient's thumbs in his hands, looking fixedly into the patient's eyes. Mesmer made "passes", moving his hands from patients' shoulders down along their arms. He then pressed his fingers on the patient's hypochondrium region (the area below the diaphragm), sometimes holding his hands there for hours. Many patients felt peculiar sensations or had convulsions that were regarded as crises and supposed to bring about the cure. Mesmer would often conclude his treatments by playing some music on a glass armonica.[13]

By 1780, Mesmer had more patients than he could treat individually and he established a collective treatment known as the "baquet." An English doctor who observed Mesmer described the treatment as follows:

In the middle of the room is placed a vessel of about a foot and a half high which is called here a "baquet". It is so large that twenty people can easily sit round it; near the edge of the lid which covers it, there are holes pierced corresponding to the number of persons who are to surround it; into these holes are introduced iron rods, bent at right angles outwards, and of different heights, so as to answer to the part of the body to which they are to be applied. Besides these rods, there is a rope which communicates between the baquet and one of the patients, and from him is carried to another, and so on the whole round. The most sensible effects are produced on the approach of Mesmer, who is said to convey the fluid by certain motions of his hands or eyes, without touching the person. I have talked with several who have witnessed these effects, who have convulsions occasioned and removed by a movement of the hand...[14]

Investigation

In 1784, without Mesmer requesting it, King Louis XVI appointed four members of the Faculty of Medicine as commissioners to investigate animal magnetism and Mesmerism. At the request of these commissioners, the king appointed Baron de Breteuil, minister of the Department of Paris, to establish investigative commissions. One was composed of individuals from the Royal Academy of Sciences, and the other of individuals the from Academy of Sciences and the Faculty of Medicine. The investigative teams included the chemist Antoine Lavoisier, the doctor Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, the astronomer Jean Sylvain Bailly, and the American ambassador Benjamin Franklin.[15][16]

The commission conducted a series of experiments aimed not just at determining whether Mesmer's treatment worked, but whether he had discovered a new physical fluid. The commission concluded that there was no evidence for such a fluid. Whatever benefit the treatment produced was attributed to "imagination". One of the commissioners, the botanist Antoine Laurent de Jussieu took exception to the official reports, authoring a dissenting opinion.[6]

The commission did not examine Mesmer specifically, but instead observed the practice of d'Eslon. They used blind trials, blindfolding the subjects, in their investigation, and the commission found that Mesmerism only seemed to work when the subject was aware of it. Their findings are considered the first observation of the placebo effect.[17] Even d'Eslon himself was convinced by the commission, stating that, "the imagination thus directed to the relief of suffering humanity would be a most valuable means in the hands of the medical profession."[15]

Mesmer was driven into exile soon after the investigations on animal magnetism. However, his influential student, Amand-Marie-Jacques de Chastenet, Marquis of Puységur (1751–1825), continued to have many followers until his death.[18]

Mesmer continued to practice in Frauenfeld, Switzerland, for a number of years. He died in 1815 in Meersburg, Germany.[19]

Works

- De planetarum influxu in corpus humanum (Über den Einfluss der Gestirne auf den menschlichen Körper) [The Influence of the Planets on the Human Body] (1766) (in Latin).

- Mémoire sur la découverte du magnetisme animal, Didot, Genf und Paris (1779) (in French). View at Gallica, from the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF).

- Sendschreiben an einen auswärtigen Arzt über die Magnetkur [Circulatory letter to an external[?] physician about the magnetic cure] (1775) (in German).

- Mémoire sur la découverte du magnétisme animal (1779)

- Précis historique des faits relatifs au magnétisme animal (1781)

- Théorie du monde et des êtres organisés suivant les principes de M…., Paris, (1784) (in French). View at Gallica, BnF.

- Aphorismes de M. Mesmer (1785)

- Mémoire de F. A. Mesmer,...sur ses découvertes (1798–1799) (in French). View at Gallica, BnF.

- Mesmerismus oder System der Wechselwirkungen. Theorie und Anwendung des thierischen Magnetismus als die allgemeine Heilkunde zur Erhaltung des Menschen [Mesmerism or the system of inter-relations. Theory and applications of animal magnetism as general medicine for the preservation of man]. Edited by Karl Christian Wolfart. Nikolai, Berlin (1814) (in German). View at Munich Digitization Center, from the Bavarian State Library.

Dramatic Portrayals

- In Mozart's Così fan tutte (1790), he is dramatized as Despina, who poisons two characters using magnets.[10]

- In Gregory Ratoff's Black Magic (1949), he was portrayed by Charles Goldner.

- In Roger Spottiswoode's Mesmer (1994), he was portrayed by Alan Rickman.

- In Marie Antoinette Series One episode The Ostrich (2023).

Notes

- "Mesmer". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Crabtree, introduction

- Prinz

- Bloch, xiii

- Pattie, 13ff.

- University, © Stanford; Stanford; California 94305 (15 March 2017). "Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815)". The Super-Enlightenment - Spotlight at Stanford. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- De Imperio Solis ac Lunae in Corpora Humana et Morbis inde Oriundis (On the Influence of the Sun and Moon upon Human Bodies and the Diseases Arising Therefrom (1704). See Pattie, 16.

- Pattie, 13

- Pattie, 30

- Steptoe, Andrew (1986). "Mozart, Mesmer and 'Cosi Fan Tutte'". Music & Letters. 67 (3): 248–255. doi:10.1093/ml/67.3.248. JSTOR 735887.

- Fenton, 105ff.

- Mackett, J., British Journal of Experimental & Clinical Hypnosis

- Gielen & Raymond, 32ff.

- Morton, Lisa (10 October 2022). Calling the Spirits: A History of Seances. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78914-281-5.

- Sadie F. Dingfelder, "The first modern psychology study: Or how Benjamin Franklin unmasked a fraud and demonstrated the power of the mind", Monitor on Psychology, July/August 2010, Vol 41, No. 7, page 30.

- University, © Stanford; Stanford; California 94305 (15 March 2017). "Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815)". The Super-Enlightenment - Spotlight at Stanford. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- "The phony health craze that inspired hypnotism". Vox. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021 – via YouTube.

- Gielen & Raymond, 39–45.

- Mesmer's grave in the Meersburg cemetery, knerger.de (in German).

References

- Bailly, J-S., "Secret Report on Mesmerism or Animal Magnetism", International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, Vol. 50, No. 4, (October 2002), pp. 364–68. doi=10.1080/00207140208410110

- Franklin, B., Majault, M. J., Le Roy, J. B., Sallin, C. L., Bailly, J-S., d'Arcet, J., de Bory, G., Guillotin, J-I., and Lavoisier, A., "Report of the Commissioners charged by the King with the Examination of Animal Magnetism", International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, Vol. 50, No. 4, (October 2002), pp. 332–63. doi=10.1080/00207140208410109

- "Classics: Memoir on the Discovery of Animal Magnetism (Franz A. Mesmer)" [Classics: Memoir on the Discovery of Animal Magnetism (Franz A. Mesmer)]. Actas Luso-españolas de Neurología, Psiquiatría y Ciencias Afines (in Spanish). 1 (5): 733–9. September 1973. ISSN 0300-5062. PMID 4593210.

- Akstein D (April 1967). "Mesmer, the Precursor of Spiritual Medicine (I)" [Mesmer, the Precursor of Spiritual Medicine (I)]. Revista Brasileira de Medicina (in Portuguese). 24 (4): 253–7. ISSN 0034-7264. PMID 4881184.

- Buranelli, V., The Wizard from Vienna: Franz Anton Mesmer, Coward, McCann & Geoghegan., (New York), 1975.

- Crabtree, Adam (1988). Animal Magnetism, Early Hypnotism, and Psychical Research, 1766–1925 – An Annotated Bibliography. White Plains, NY: Kraus International. ISBN 0-527-20006-9

- Darnton, Robert (1968). Mesmerism and the End of the Enlightenment in France. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-56951-5.

- Donaldson, I.M.L., "Mesmer's 1780 Proposal for a Controlled Trial to Test his Method of Treatment Using 'Animal Magnetism'", Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, Vol.98, No.12, (December 2005), pp. 572–575.

- Eckert H (1955). "An Unknown Portrait of Franz Anton Mesmer" [An Unknown Portrait of Franz Anton Mesmer]. Gesnerus (in German). 12 (1–2): 44–6. doi:10.1163/22977953-0120102004. ISSN 0016-9161. PMID 13305809.

- Ellenberger, Henri (1970). The Discovery of the Unconscious. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01672-3.

- Fenton, Peter Robert (1996). Shaolin Nei Jin Qi Gong: Ancient Healing in the Modern World. York Beach: Samuel Weiser. ISBN 978-0-87728-876-3.

- Forrest D (October 2002). "Mesmer". The International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 50 (4): 295–308. doi:10.1080/00207140208410106. ISSN 0020-7144. PMID 12362948. S2CID 214652295.

- Gallo DA, Finger S (November 2000). "The Power of a Musical Instrument: Franklin, the Mozarts, Mesmer, and the Glass Armonica". History of Psychology. 3 (4): 326–43. doi:10.1037/1093-4510.3.4.326. ISSN 1093-4510. PMID 11855437.

- Gielen, Uwe; Raymond, Jeannette (2015). "The curious birth of psychological healing in the Western World (1775-1825): From Gaβner to Mesmer to Puységur.". In Rich, Grant; Gielen, Uwe (eds.). Pathfinders in international psychology. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. pp. 25–51.

- Goldsmith, M., Franz Anton Mesmer: A History of Mesmerism, Doubleday, Doran & Co., (New York), 1934.

- Gould, Stephen (1991). Bully for Brontosaurus. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-30857-0.

- Gravitz MA (July 1994). "The First Use of Self-Hypnosis: Mesmer Mesmerizes Mesmer". The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 37 (1): 49–52. doi:10.1080/00029157.1994.10403109. ISSN 0002-9157. PMID 8085546.

- Harte, R., Hypnotism and the Doctors, Volume I: Animal Magnetism: Mesmer/De Puysegur, L.N. Fowler & Co., (London), 1902.

- Iannini R (1992). "Mesmer and mesmerism" [Mesmer and Mesmerism]. Medicina Nei Secoli (in Italian). 4 (3): 71–83. ISSN 0394-9001. PMID 11640137.

- Kihlstrom JF (October 2002). "Mesmer, the Franklin Commission, and Hypnosis: A Counterfactual Essay". The International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 50 (4): 407–19. doi:10.1080/00207140208410114. ISSN 0020-7144. PMID 12362956. S2CID 12252837.

- Lopez CA (July 1993). "Franklin and Mesmer: An Encounter". Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 66 (4): 325–31. ISSN 0044-0086. PMC 2588895. PMID 8209564.

- Mackett, J (June 1989). "Chinese Hypnosis". British Journal of Experimental & Clinical Hypnosis. 6 (2): 129–130. ISSN 0265-1033.

- Makari GJ (February 1994). "Franz Anton Mesmer and the Case of the Blind Pianist". Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 45 (2): 106–10. doi:10.1176/ps.45.2.106. ISSN 0022-1597. PMID 8168786.

- Mesmer, Franz (1980). Mesmerism. Los Altos: W. Kaufman. ISBN 978-0-913232-88-0.

- Miodoński L (2001). "Romantic Medicine in Germany as the Philosophical Explication for Understanding the World and Man – Mesmer and Mesmerism" [Romantic Medicine in Germany as the Philosophical Explication for Understanding the World and Man – Mesmer and Mesmerism]. Medycyna Nowozytna (in Polish). 8 (2): 5–32. ISSN 1231-1960. PMID 12568094.

- Parish D (February 1990). "Mesmer and His Critics". New Jersey Medicine: The Journal of the Medical Society of New Jersey. 87 (2): 108–10. ISSN 0885-842X. PMID 2407974.

- Pattie, F.A., "Mesmer's Medical Dissertation and Its Debt to Mead's De Imperio Solis ac Lunae", Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Vol.11, (July 1956), pp. 275–287.

- Pattie, Frank (1994). Mesmer and Animal Magnetism: A Chapter in the History of Medicine. Hamilton: Edmonston Pub. ISBN 978-0-9622393-5-9.

- Pattie FA (July 1979). "A Mesmer-Paradis Myth Dispelled". The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 22 (1): 29–31. doi:10.1080/00029157.1979.10403997. ISSN 0002-9157. PMID 386774.

- Prinz, Armin (1994). Mesmer, Franz Anton in: Neue Deutsche Biographie 17. http://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd118581309.html

- Schott H (1982). "Die Mitteilung des Lebensfeuers. Zum therapeutischen Konzept von Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815)". Medizinhistorisches Journal. 17 (3): 195–214. ISSN 0025-8431. PMID 11615917.

- Schott H (1984). "Mesmer, Braid and Bernheim: On the History of the Development of Hypnotism" [Mesmer, Braid and Bernheim: On the History of the Development of Hypnotism]. Gesnerus (in German). 41 (1–2): 33–48. doi:10.1163/22977953-0410102002. ISSN 0016-9161. PMID 6378725.

- Shultheisz E (July 1965). "Mesmer and Mesmerism" [Mesmer and Mesmerism]. Orvosi Hetilap (in Hungarian). 106: 1427–30. ISSN 0030-6002. PMID 14347842.

- Spiegel D (October 2002). "Mesmer Minus Magic: Hypnosis and Modern Medicine". The International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 50 (4): 397–406. doi:10.1080/00207140208410113. ISSN 0020-7144. PMID 12362955. S2CID 22014593.

- Stone MH (Spring 1974). "Mesmer and His Followers: The Beginnings of Sympathetic Treatment of Childhood Emotional Disorders" (Free full text). History of Childhood Quarterly. 1 (4): 659–79. ISSN 0091-4266. PMID 11614567.

- Voegele GE (April 1956). "The Relation of Mesmer to Mozart". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 112 (10): 848–9. doi:10.1176/ajp.112.10.848. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 13302494.

- Watkins D (May 1976). "Franz Anton Mesmer: Founder of Psychotherapy". Nursing Mirror and Midwives Journal. 142 (22): 66–7. ISSN 0143-2524. PMID 778805.

- Winter, A., Mesmerized: Powers of Mind in Victorian Britain, The University of Chicago Press, (Chicago), 1998.

- Wyckoff, J. [1975], Franz Anton Mesmer: Between God and Devil, Prentice-Hall, (Englewood Cliffs), 1975.

External links

- Mesmer's 27 Propositions at the Wayback Machine (archived 10 July 2004)

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- "Condorcet and mesmerism: a record in the history of scepticism", Condorcet manuscript (1784), online and analyzed on Bibnum [click 'à télécharger' for English version].