Requiem (Verdi)

The Messa da Requiem (at one time referred to as the Manzoni Requiem[1]) is a musical setting of the Catholic funeral mass (Requiem) for four soloists, double choir and orchestra by Giuseppe Verdi. It was composed in memory of Alessandro Manzoni, whom Verdi admired. The first performance, at the San Marco church in Milan on 22 May 1874, marked the first anniversary of Manzoni's death.

| Messa da Requiem | |

|---|---|

| Requiem by Giuseppe Verdi | |

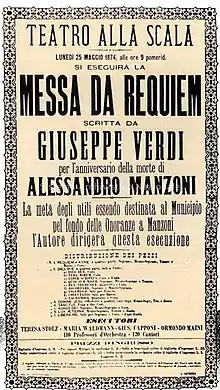

_Titelblatt_(1874).jpg.webp) First edition title page, Ricordi, 1874 | |

| Related | Messa per Rossini |

| Occasion | In memory of Alessandro Manzoni |

| Text | Requiem |

| Language | Latin |

| Performed | 22 May 1874 |

| Scoring |

|

Considered too operatic to be performed in a liturgical setting, it is usually given in concert form of around 90 minutes in length. Musicologist David Rosen calls it "probably the most frequently performed major choral work composed since the compilation of Mozart's Requiem".[2]

Composition history

After Gioachino Rossini's death in 1868, Verdi suggested that a number of Italian composers collaborate on a Requiem in Rossini's honor. He began the effort by submitting the concluding movement, the "Libera me". During the next year a Messa per Rossini was compiled by Verdi and twelve other famous Italian composers of the time. The premiere was scheduled for 13 November 1869, the first anniversary of Rossini's death.

However, on 4 November, nine days before the premiere, the organising committee abandoned it. Verdi blamed this on the scheduled conductor, Angelo Mariani. He pointed to Mariani's lack of enthusiasm for the project, although in fact the conductor had not been a part of the organising committee and did his best to support Verdi,[3] this episode marked the beginning of the end of their friendship. The composition remained unperformed until 1988, when Helmuth Rilling premiered the complete Messa per Rossini in Stuttgart, Germany.

In the meantime, Verdi kept toying with his "Libera me", frustrated that the combined commemoration of Rossini's life would not be performed in his lifetime.

On 22 May 1873, the Italian writer and humanist Alessandro Manzoni, whom Verdi had admired all his adult life and met in 1868, died. Upon hearing of his death, Verdi resolved to complete a Requiem—this time entirely of his own writing—for Manzoni. Verdi traveled to Paris in June, where he commenced work on the Requiem, giving it the form we know today. It included a revised version of the "Libera me" originally composed for Rossini.

Performance history

19th century

The Requiem was first performed in the church of San Marco in Milan on 22 May 1874, the first anniversary of Manzoni's death. Verdi himself conducted, and the four soloists were Teresa Stolz (soprano), Maria Waldmann (mezzo-soprano), Giuseppe Capponi (tenor) and Ormondo Maini (bass).[4]

As Aida, Amneris and Ramfis respectively, Stolz, Waldmann, and Maini had all sung in the European premiere of Aida in 1872, and Capponi was also intended to sing the role of Radames at that premiere but was replaced due to illness. Teresa Stolz went on to a brilliant career, Waldmann retired very young in 1875, but the male singers appear to have faded into obscurity. Also, Teresa Stolz was engaged to Angelo Mariani in 1869, but she later left him.

The Requiem was repeated at La Scala three days later on 25 May with the same soloists and Verdi again conducting.[5] It won immediate contemporary success, although not everywhere. It received seven performances at the Opéra-Comique in Paris, but the new Royal Albert Hall in London could not be filled for such a Catholic occasion. In Venice, impressive Byzantine ecclesiastical decor was designed for the occasion of the performance.

Its debut performance in the United States was in Boston in 1878, by the still thriving, Handel and Haydn Society.[6]

It later disappeared from the standard choral repertoire, but made a reappearance in the 1930s and is now regularly performed and a staple of many choral societies.[7]

20th century and beyond

The Requiem was reportedly performed approximately 16 times between 1943 and 1944 by prisoners in the concentration camp of Theresienstadt (also known as Terezín) under the direction of Rafael Schächter. The performances were presented under the auspices of the Freizeitgestaltung, a cultural organization in the Ghetto.[8]

Since the 1990s, commemorations in the US and Europe have included memorial performances of the Requiem in honor of the Terezín performances. On the heels of previous performances held at the Terezín Memorial, Murry Sidlin performed the Requiem in Terezin in 2006 and rehearsed the choir in the same basement where the original inmates reportedly rehearsed. Part of the Prague Spring Festival, two children of survivors sang in the choir with their parents sitting in the audience.[9][10][11]

The Requiem has been staged in a variety of ways several times in recent years. Achim Freyer created a production for the Deutsche Oper Berlin in 2006 that was revived in 2007, 2011 and 2013.[12] In Freyer's staging, the four sung roles, "Der Weiße Engel" (The White Angel), "Der Tod-ist-die-Frau" (Death is the Woman), "Einsam" (Solitude), and "Der Beladene" (The Load Bearer) are complemented by choreographed allegorical characters.[13]

In 2011, Oper Köln premiered a full staging by Clemens Bechtel where the four main characters were shown in different life and death situations: the Fukushima nuclear disaster, a Turkish writer in prison, a young woman with bulimia, and an aid worker in Africa.[14][15]

In 2021, the New York Metropolitan Opera performed the Requiem for the 20th anniversary of the September 11 attacks.[16]

Versions and arrangements

For a Paris performance, Verdi revised the "Liber scriptus" to allow Maria Waldmann a further solo for future performances.[7] Previously, the movement had been set for a choral fugue in a classical Baroque style. With its premiere at the Royal Albert Hall performance in May 1875, this revision became the definitive edition that has been most performed since, although the original version is included in critical editions of the work published by Bärenreiter and University of Chicago Press.

Versions accompanied by four pianos or brass band were also performed.

Franz Liszt transcribed the Agnus Dei for solo piano (S. 437). It has been recorded by Leslie Howard.

Sections

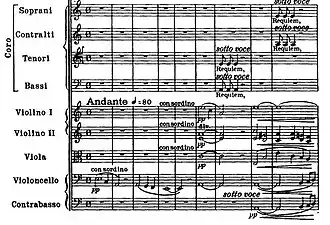

- 1. Requiem

- Introit (chorus)

- Kyrie (soloists, chorus)

- 2. Dies irae

- Dies irae (chorus)

- Tuba mirum (chorus)

- Mors stupebit (bass)

- Liber scriptus (mezzo-soprano, chorus – chorus only in original version)

- Quid sum miser (soprano, mezzo-soprano, tenor)

- Rex tremendae (soloists, chorus)

- Recordare (soprano, mezzo-soprano)

- Ingemisco (tenor)

- Confutatis maledictis (bass, chorus)

- Lacrymosa (soloists, chorus)

- 3. Offertory

- Domine Jesu Christe (soloists)

- Hostias (soloists)

- 4. Sanctus (double chorus)

- 5. Agnus Dei (soprano, mezzo-soprano, chorus)

- 6. Lux aeterna (mezzo-soprano, tenor, bass)

- 7. Libera me (soprano, chorus)

- Libera me

- Dies irae

- Requiem aeternam

- Libera me

Music

Throughout the work, Verdi uses vigorous rhythms, sublime melodies, and dramatic contrasts—much as he did in his operas—to express the powerful emotions engendered by the text. The terrifying (and instantly recognizable) "Dies irae" that introduces the traditional sequence of the Latin funeral rite is repeated throughout. Trumpets surround the stage to produce a call to judgement in the "Tuba mirum", and the almost oppressive atmosphere of the "Rex tremendae" creates a sense of unworthiness before the King of Tremendous Majesty. Yet the well-known tenor solo "Ingemisco" radiates hope for the sinner who asks for the Lord's mercy.

The "Sanctus" (a complicated eight-part fugue scored for double chorus) begins with a brassy fanfare to announce him "who comes in the name of the Lord". Finally the "Libera me", the oldest music by Verdi in the Requiem, interrupts. Here the soprano cries out, begging, "Deliver me, Lord, from eternal death ... when you will come to judge the world by fire."

When the Requiem was composed, female singers were not permitted to perform in Catholic Church rituals (such as a requiem mass).[17] However, from the beginning Verdi intended to use female singers in the work. In his open letter proposing the Requiem project (when it was still conceived as a multi-author Requiem for Rossini), Verdi wrote: "If I were in the good graces of the Holy Father—Pope Pius IX—I would beg him to permit—if only for this one time—that women take part in the performance of this music; but since I am not, it will fall to someone else better suited to obtain this decree."[18] In the event, when Verdi composed the Requiem alone, two of the four soloists were sopranos, and the chorus included female voices. This may have slowed the work's acceptance in Italy.[17]

At the time of its premiere, the Requiem was criticized by some as being too operatic in style for the religious subject matter.[17] According to Gundula Kreuzer, "Most critics did perceive a schism between the religious text (with all its musical implications) and Verdi's setting." Some viewed it negatively as "an opera in ecclesiastical robes", or alternatively, as a religious work, but one in "dubious musical costume". While the majority of critics agreed that the music was "dramatic", some felt that such treatment of the text was appropriate, or at least permissible.[17] As to the quality of the music, the critical consensus agreed that the work displayed "fluent invention, beautiful sound effects and charming vocal writing". Critics were divided between praise and condemnation with respect to Verdi's willingness to break standard compositional rules for musical effect, such as his use of consecutive fifths.[17]

Instrumentation

The work is scored for the following orchestra:

- woodwind: 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 4 bassoons

- brass: 4 horns, 8 trumpets (4 offstage), 3 trombones, ophicleide[instr 1]

- percussion: timpani, bass drum

- strings: violins I, II, violas, violoncellos, double basses.

Recordings

References

Notes

- Summer 2007, p. .

- Rosen 1995, p. vii.

- Frank Walker. The man Verdi. — New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1962. — P. 350—361.

- Messa da Requiem Archived 2013-12-31 at the Wayback Machine, on giuseppeverdi.it. Retrieved 29 December 2013

- Resigno 2001, p. 14.

- "H+H's Baroque and Classical Music History".

- CD liner notes (Verdi: Requiem / Quattro pezzi sacri). Naxos Records. 1997. 8.550944-45.

- "Requiem | Okanagan Symphony Orchestra". Retrieved 2019-01-12.

- Jeremy Eichler, "Honoring the conductor who gave Terezin its Requiem", The Boston Globe, April 5, 2013

- "Defiant Requiem: Verdi at Terezin" on pbs.org. Retrieved 29 December 2013: See Theresienstadt concentration camp for "Terezin"

- "Rafael Schächter" on holocaustmusic.ort.org. Retrieved 29 December 2013

- "Giuseppe Verdi: Messa da Requiem": Trailer for Deutsche Oper's dramatic staging of the work on youtube.com

- Jean-Luc Vannier, "Messa da Requiem de Verdi d’une sombre beauté au Deutsche Oper de Berlin" (in French)

- Oper Köln website details of the staging by Clemens Bechtel. (In German) Archived 2013-12-30 at the Wayback Machine on operkoeln.com

- Review: Cologne Opera staging of the Bechtel version Archived 2013-12-30 at the Wayback Machine (in German) on der-neue-merker. (in German)

- "Verdi's Requiem: The Met Remembers 9/11". Metropolitan Opera. September 11, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- Kreuzer 2010, pp. 60–61

- Gazzetta Piemontese (in Italian). 22 November 1868. p. 3.

Se io fossi nelle buone grazie del Santo Padre, lo pregherei a voler permettere, almeno per questa sola volta, che le donne prendessero parte all'esecuzione di questa musica, ma non essendolo, converrá trovar persona piu di me idonea ad ottenere l'intento

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Sources

- Holroyd, Michael (1997). Bernard Shaw: A Biography. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 07011-6279-1.

- Kreuzer, Gundula (2010). Verdi and the Germans: From Unification to the Third Reich. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51919-9.

- Resigno, Eduardo (2001). Dizionario Verdiano. Biblioteca Universale Rizzoli. ISBN 88-17-86628-8.

- Rosen, David (1995). Verdi: Requiem. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39448-1.

- Summer, Robert J. (2007). Choral Masterworks from Bach to Britten: Reflections of a Conductor. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5903-6.

Further reading

- Kennedy, Michael (2006), The Oxford Dictionary of Music. ISBN 0-19-861459-4

- Verdi, Giuseppe; (Ed., Marco Uvietta, 2014) Messa da requiem. Critical edition. Kassel: Bärenreiter.

External links

- Digitised copy of Verdi's Messa Da Requiem published by Ricordi in Milan 1874, from National Library of Scotland.

- Live Recording of Liber Scriptus portion of Requiem (Mary Gayle Greene, mezzo-soprano)

- Requiem (Verdi): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Free scores of Requiem (Verdi) in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)