Michel de Montaigne

Michel Eyquem, Seigneur de Montaigne (/mɒnˈteɪn/ mon-TAYN;[3] French: [miʃɛl ekɛm də mɔ̃tɛɲ]; 28 February 1533 – 13 September 1592[4]), commonly known as Michel de Montaigne, was one of the most significant philosophers of the French Renaissance. He is known for popularizing the essay as a literary genre. His work is noted for its merging of casual anecdotes[5] and autobiography with intellectual insight. Montaigne had a direct influence on numerous Western writers; his massive volume Essais contains some of the most influential essays ever written.

Michel de Montaigne | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Montaigne, 1570s | |

| Born | 28 February 1533 Château de Montaigne, Guyenne, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 13 September 1592 (aged 59) Château de Montaigne, Guyenne, Kingdom of France |

| Education | College of Guienne |

| Era | |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas |

|

| Signature | |

| |

During his lifetime, Montaigne was admired more as a statesman than as an author. The tendency in his essays to digress into anecdotes and personal ruminations was seen as detrimental to proper style rather than as an innovation, and his declaration that "I am myself the matter of my book" was viewed by his contemporaries as self-indulgent. In time, however, Montaigne came to be recognized as embodying, perhaps better than any other author of his time, the spirit of freely entertaining doubt that began to emerge at that time. He is most famously known for his skeptical remark, ''Que sçay-je?" ("What do I know?", in Middle French; now rendered as "Que sais-je?" in modern French).

Biography

Family, childhood and education

Montaigne was born in the Aquitaine region of France, on the family estate Château de Montaigne in a town now called Saint-Michel-de-Montaigne, close to Bordeaux. The family was very wealthy. His great-grandfather, Ramon Felipe Eyquem, had made a fortune as a herring merchant - and had bought the estate in 1477, thus becoming the Lord of Montaigne. His father, Pierre Eyquem, Seigneur of Montaigne, was a French Catholic soldier in Italy for a time, and had also been the mayor of Bordeaux.[4]

Although there were several families bearing the patronym "Eyquem" in Guyenne, his father's family is thought to have had some degree of Marrano (Spanish and Portuguese Jewish) origins,[6] while his mother, Antoinette López de Villanueva, was a convert to Protestantism.[7] His maternal grandfather, Pedro López,[8] from Zaragoza, was from a wealthy Marrano (Sephardic Jewish) family, that had converted to Catholicism.[9][10][11][12] His maternal grandmother, Honorette Dupuy, was from a Catholic family in Gascony, France.[13]

During a great part of Montaigne's life his mother lived near him, and even survived him; but she is mentioned only twice in his essays. Montaigne's relationship with his father however is frequently reflected upon and discussed in his essays.[14]

Montaigne's education began in early childhood, and followed a pedagogical plan, that his father had developed, refined by the advice of the latter's humanist friends. Soon after his birth Montaigne was brought to a small cottage, where he lived the first three years of life in the sole company of a peasant family, in order to, according to the elder Montaigne, "draw the boy close to the people, and to the life conditions of the people, who need our help".[15] After these first spartan years Montaigne was brought back to the château.

Another objective was for Latin to become his first language. The intellectual education of Montaigne was assigned to a German tutor (a doctor named Horstanus, who could not speak French). His father hired only servants who could speak Latin, and they also were given strict orders always to speak to the boy in Latin. The same rule applied to his mother, father, and servants, who were obliged to use only Latin words he employed; and thus they acquired a knowledge of the very language his tutor taught him. Montaigne's Latin education was accompanied by constant intellectual and spiritual stimulation. He was familiarized with Greek by a pedagogical method that employed games, conversation, and exercises of solitary meditation, rather than the more traditional books.[16]

The atmosphere of the boy's upbringing engendered in him a spirit of "liberty and delight" - that he would later describe as making him "relish...duty by an unforced will, and of my own voluntary motion...without any severity or constraint". His father had a musician wake him every morning, playing one instrument or another;[17] and an epinettier (with a zither) was the constant companion to Montaigne and his tutor, playing tunes to alleviate boredom and tiredness.

Around the year 1539 Montaigne was sent to study at a highly regarded boarding school in Bordeaux, the College of Guienne, then under the direction of the greatest Latin scholar of the era, George Buchanan, where he mastered the whole curriculum by his thirteenth year. He finished the first phase of his educational studies at the College of Guienne in 1546.[18] He then began his study of law (his alma mater remains unknown, since there are no certainties about his activity from 1546 to 1557)[19] and entered a career in the local legal system.

Career and marriage

Montaigne was a counselor of the Court des Aides of Périgueux, and in 1557 he was appointed counselor of the Parlement in Bordeaux, a high court. From 1561 to 1563 he was courtier at the court of Charles IX, and he was present with the king at the siege of Rouen (1562). He was awarded the highest honour of the French nobility, the collar of the Order of Saint Michael.[20]

While serving at the Bordeaux Parlement, he became a very close friend of the humanist poet Étienne de La Boétie, whose death in 1563 deeply affected Montaigne. It has been suggested by Donald M. Frame - in his introduction to The Complete Essays of Montaigne - that because of Montaigne's "imperious need to communicate", after losing Étienne, he began the Essais as a new "means of communication", and that "the reader takes the place of the dead friend".[21]

Montaigne married Françoise de la Cassaigne in 1565, probably in an arranged marriage. She was the daughter and niece of wealthy merchants of Toulouse and Bordeaux. They had six daughters, but only the second-born, Léonor, survived infancy.[22] He wrote very little about the relationship with his wife, and little is known about their marriage. Of his daughter Léonor he wrote: "All my children die at nurse; but Léonore, our only daughter, who has escaped this misfortune, has reached the age of six and more, without having been punished, the indulgence of her mother aiding, except in words, and those very gentle ones."[23] His daughter married François de la Tour and later Charles de Gamaches. She had a daughter by each.[24]

Writing

Following the petition of his father, Montaigne started to work on the first translation of the Catalan monk Raymond Sebond's Theologia naturalis, which he published a year after his father's death in 1568 (in 1595 Sebond's Prologue was put on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum because of its declaration that the Bible is not the only source of revealed truth). Montaigne also published a posthumous edition of the works of his friend, Boétie.[25]

In 1570 he moved back to the family estate, the Château de Montaigne, which he had inherited. He thus became the Lord of Montaigne. Around this time he was seriously injured in a riding accident on the grounds of the château when one of his mounted companions collided with him at speed, throwing Montaigne from his horse and briefly knocking him unconscious.[26] It took weeks or months for him to recover, and this close brush with death apparently affected him greatly, as he discussed it at length in his writings over the following years. Not long after the accident he relinquished his magistracy in Bordeaux, his first child was born (and died a few months later), and by 1571 he had retired from public life completely, to the tower of the château – his so-called "citadel" – where he almost totally isolated himself from every social and family affair. Locked up in his library, which contained a collection of some 1,500 volumes, he began work on the writings that would later be compiled into his Essais ("Essays"), first published in 1580. On the day of his 38th birthday, as he entered this almost ten-year period of self-imposed reclusion, he had the following inscription placed on the crown of the bookshelves of his working chamber:

In the year of Christ 1571, at the age of thirty-eight, on the last day of February, his birthday, Michael de Montaigne, long weary of the servitude of the court and of public employments, while still entire, retired to the bosom of the learned virgins, where in calm and freedom from all cares he will spend what little remains of his life, now more than half run out. If the fates permit, he will complete this abode, this sweet ancestral retreat; and he has consecrated it to his freedom, tranquility, and leisure.[27]

Château de Montaigne, a house built on the land once owned by Montaigne's family. His original family home no longer exists, although the tower in which he wrote still stands.

Château de Montaigne, a house built on the land once owned by Montaigne's family. His original family home no longer exists, although the tower in which he wrote still stands. The Tour de Montaigne (Montaigne's tower), where Montaigne's library was located, remains mostly unchanged since the sixteenth century.

The Tour de Montaigne (Montaigne's tower), where Montaigne's library was located, remains mostly unchanged since the sixteenth century.

Travels

During this time of the Wars of Religion in France, Montaigne, a Roman Catholic,[28] acted as a moderating force,[29] respected both by the Catholic King Henry III and the Protestant Henry of Navarre, who later converted to Catholicism.

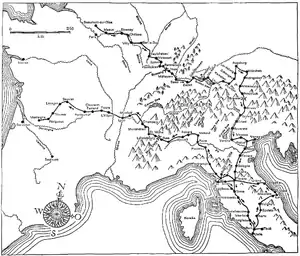

In 1578 Montaigne, whose health had always been excellent, started suffering from painful kidney stones, a tendency he inherited from his father's family. Throughout this illness he would have nothing to do with doctors or drugs.[4] From 1580 to 1581 Montaigne traveled in France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy, partly in search of a cure, establishing himself at Bagni di Lucca, where he took the waters. His journey was also a pilgrimage to the Holy House of Loreto, to which he presented a silver relief (depicting him, his wife, and their daughter, kneeling before the Madonna) considering himself fortunate that it should be hung on a wall within the shrine.[30] He kept a journal, recording regional differences and customs[31] - and a variety of personal episodes, including the dimensions of the stones he succeeded in expelling. This was published much later, in 1774, after its discovery in a trunk, that is displayed in his tower.[32]

During a visit to the Vatican that Montaigne described in his travel journal, the Essais were examined by Sisto Fabri, who served as Master of the Sacred Palace under Pope Gregory XIII. After Fabri examined Montaigne's Essais, the text was returned to him on 20 March 1581. Montaigne had apologized for references to the pagan notion of "fortuna", as well as for writing favorably of Julian the Apostate and of heretical poets, and was released to follow his own conscience in making emendations to the text.[33]

Later career

While in the city of Lucca in 1581 he learned that, like his father before him, he had been elected mayor of Bordeaux. He thus returned and served as mayor. He was re-elected in 1583 and served until 1585, again moderating between Catholics and Protestants. The plague broke out in Bordeaux toward the end of his second term in office, in 1585. In 1586 the plague and the French Wars of Religion prompted him to leave his château for two years.[4]

Montaigne continued to extend, revise, and oversee the publication of the Essais. In 1588 he wrote its third book - and also met Marie de Gournay, an author, who admired his work, and later edited and published it. Montaigne later referred to her as his adopted daughter.[4]

When King Henry III was assassinated in 1589, Montaigne, despite his aversion to the cause of The Reformation, was anxious to promote a compromise, that would end the bloodshed, and gave his support to Henry of Navarre, who would go on to become King Henry IV. Montaigne's position associated him with the politiques, the establishment movement that prioritised peace, national unity, and royal authority over religious allegiance.[34]

Death

Montaigne died of quinsy at the age of 59 in 1592 at the Château de Montaigne. In his case the disease "brought about paralysis of the tongue",[35] especially difficult for one who once said: "the most fruitful and natural play of the mind is conversation. I find it sweeter than any other action in life; and if I were forced to choose, I think I would rather lose my sight than my hearing and voice."[36] Remaining in possession of all his other faculties, he requested Mass, and died during the celebration of that Mass.[37]

He was buried nearby. Later his remains were moved to the church of Saint Antoine at Bordeaux. The church no longer exists. It became the Convent des Feuillants, which also has disappeared.[38]

Essais

His humanism finds expression in his Essais, a collection of a large number of short subjective essays on various topics published in 1580 that were inspired by his studies in the classics, especially by the works of Plutarch and Lucretius.[39] Montaigne's stated goal was to describe humans, and especially himself, with utter frankness.

Inspired by his consideration of the lives and ideals of the leading figures of his age, he finds the great variety and volatility of human nature to be its most basic features. He describes his own poor memory, his ability to solve problems and mediate conflicts without truly getting emotionally involved, his disdain for the human pursuit of lasting fame, and his attempts to detach himself from worldly things to prepare for his timely death. He writes about his disgust with the religious conflicts of his time. He believed that humans are not able to attain true certainty. The longest of his essays, Apology for Raymond Sebond, marking his adoption of Pyrrhonism,[40] contains his famous motto, "What do I know?"

Montaigne considered marriage necessary for the raising of children but disliked strong feelings of passionate love because he saw them as detrimental to freedom. In education, he favored concrete examples and experience over the teaching of abstract knowledge intended to be accepted uncritically. His essay "On the Education of Children" is dedicated to Diana of Foix.

The Essais exercised an important influence on both French and English literature, in thought and style.[41] Francis Bacon's Essays, published over a decade later, first in 1597, usually are presumed to be directly influenced by Montaigne's collection, and Montaigne is cited by Bacon alongside other classical sources in later essays.[42]

Montaigne's influence on psychology

Although not a scientist, Montaigne made observations on topics in psychology.[43] In his essays, he developed and explained his observations of these themes. His thoughts and ideas covered subjects such as thought, motivation, fear, happiness, child education, experience, and human action. Montaigne's ideas have influenced psychology and are a part of its rich history.

Child education

Child education was among the psychological topics that he wrote about.[43] His essays On the Education of Children, On Pedantry, and On Experience explain the views he had on child education.[44]: 61 : 62 : 70 Some of his views on child education are still relevant today.[45]

Montaigne's views on the education of children were opposed to the common educational practices of his day.[44]: 63 : 67 He found fault both with what was taught and how it was taught.[44]: 62 Much of education during Montaigne's time focused on reading the classics and learning through books.[44]: 67 Montaigne disagreed with learning strictly through books. He believed it was necessary to educate children in a variety of ways. He also disagreed with the way information was being presented to students. It was being presented in a way that encouraged students to take the information that was taught to them as absolute truth. Students were denied the chance to question the information; but Montaigne, in general, took the position that to learn truly, a student had to take the information and make it their own:

Let the tutor make his charge pass everything through a sieve and lodge nothing in his head on mere authority and trust: let not Aristotle's principles be principles to him any more than those of the Stoics or Epicureans. Let this variety of ideas be set before him; he will choose if he can; if not, he will remain in doubt. Only the fools are certain and assured. "For doubting pleases me no less than knowing." [Dante]. For if he embraces Xenophon's and Plato's opinions by his own reasoning, they will no longer be theirs, they will be his. He who follows another follows nothing. He finds nothing; indeed he seeks nothing. "We are not under a king; let each one claim his own freedom." [Seneca]. . . . He must imbibe their way of thinking, not learn their precepts. And let him boldly forget, if he wants, where he got them, but let him know how to make them his own. Truth and reason are common to everyone, and no more belong to the man who first spoke them than to the man who says them later. It is no more according to Plato than according to me, since he and I see it in the same way. The bees plunder the flowers here and there, but afterward they make of them honey, which is all theirs[.][46]

At the foundation, Montaigne believed that the selection of a good tutor was important for the student to become well educated.[44]: 66 Education by a tutor was to be conducted at the pace of the student.[44]: 67 He believed that a tutor should be in dialogue with the student, letting the student speak first. The tutor also should allow for discussions and debates to be had. Such a dialogue was intended to create an environment in which students would teach themselves. They would be able to realize their mistakes and make corrections to them as necessary.

Individualized learning was integral to his theory of child education. He argued that the student combines information already known with what is learned and forms a unique perspective on the newly learned information.[47]: 356 Montaigne also thought that tutors should encourage the natural curiosity of students and allow them to question things.[44]: 68 He postulated that successful students were those who were encouraged to question new information and study it for themselves, rather than simply accepting what they had heard from the authorities on any given topic. Montaigne believed that a child's curiosity could serve as an important teaching tool when the child is allowed to explore the things that the child is curious about.

Experience also was a key element to learning for Montaigne. Tutors needed to teach students through experience rather than through the mere memorization of information often practised in book learning.[44]: 62 : 67 He argued that students would become passive adults, blindly obeying and lacking the ability to think on their own.[47]: 354 Nothing of importance would be retained and no abilities would be learned.[44]: 62 He believed that learning through experience was superior to learning through the use of books.[45] For this reason he encouraged tutors to educate their students through practice, travel, and human interaction. In doing so, he argued that students would become active learners, who could claim knowledge for themselves.

Montaigne's views on child education continue to have an influence in the present. Variations of Montaigne's ideas on education are incorporated into modern learning in some ways. He argued against the popular way of teaching in his day, encouraging individualized learning. He believed in the importance of experience, over book learning and memorization. Ultimately, Montaigne postulated that the point of education was to teach a student how to have a successful life by practising an active and socially interactive lifestyle.[47]: 355

Related writers and influence

Thinkers exploring ideas similar to Montaigne include Erasmus, Thomas More, John Fisher, and Guillaume Budé, who all worked about fifty years before Montaigne.[48] Many of Montaigne's Latin quotations are from Erasmus' Adagia, and most critically, all of his quotations from Socrates. Plutarch remains perhaps Montaigne's strongest influence, in terms of substance and style.[49] Montaigne's quotations from Plutarch in the Essays number more than 500.[50]

Ever since Edward Capell first made the suggestion in 1780, scholars have suggested Montaigne to be an influence on Shakespeare.[51] The latter would have had access to John Florio's translation of Montaigne's Essais, published in English in 1603, and a scene in The Tempest "follows the wording of Florio [translating Of Cannibals] so closely that his indebtedness is unmistakable".[52] Most parallels between the two may be explained, however, as commonplaces:[51] as similarities with writers in other nations to the works of Cervantes and Shakespeare could be due simply to their own study of Latin moral and philosophical writers such as Seneca the Younger, Horace, Ovid, and Virgil.

Much of Blaise Pascal's skepticism in his Pensées has been attributed traditionally to his reading Montaigne.[53]

The English essayist William Hazlitt expressed boundless admiration for Montaigne, exclaiming that "he was the first who had the courage to say as an author what he felt as a man. ... He was neither a pedant nor a bigot. ... In treating of men and manners, he spoke of them as he found them, not according to preconceived notions and abstract dogmas".[54] Beginning most overtly with the essays in the "familiar" style in his own Table-Talk, Hazlitt tried to follow Montaigne's example.[55]

Ralph Waldo Emerson chose "Montaigne; or, the Skeptic" as a subject of one of his series of lectures entitled, Representative Men, alongside other subjects such as Shakespeare and Plato. In "The Skeptic" Emerson writes of his experience reading Montaigne, "It seemed to me as if I had myself written the book, in some former life, so sincerely it spoke to my thought and experience." Friedrich Nietzsche judged of Montaigne: "That such a man wrote has truly augmented the joy of living on this Earth".[56] Sainte-Beuve advises us that "to restore lucidity and proportion to our judgments, let us read every evening a page of Montaigne."[57] Stefan Zweig drew inspiration from one of Montaigne's quotes to give the title to one of his autobiographical novels, "A Conscience Against Violence."[58]

| Part of a series on |

| Pyrrhonism |

|---|

|

|

|

The American philosopher Eric Hoffer employed Montaigne both stylistically and in thought. In Hoffer's memoir, Truth Imagined, he said of Montaigne, "He was writing about me. He knew my innermost thoughts." The British novelist John Cowper Powys expressed his admiration for Montaigne's philosophy in his books, Suspended Judgements (1916)[59] and The Pleasures of Literature (1938). Judith N. Shklar introduces her book Ordinary Vices (1984), "It is only if we step outside the divinely ruled moral universe that we can really put our minds to the common ills we inflict upon one another each day. That is what Montaigne did and that is why he is the hero of this book. In spirit he is on every one of its pages..."

Twentieth-century literary critic Erich Auerbach called Montaigne the first modern man. "Among all his contemporaries", writes Auerbach (Mimesis, Chapter 12), "he had the clearest conception of the problem of man's self-orientation; that is, the task of making oneself at home in existence without fixed points of support".[60]

Discovery of remains

The Musée d'Aquitaine announced on 20 November 2019 that the human remains, which had been found in the basement of the museum a year earlier, might belong to Montaigne.[61] Investigation of the remains, postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic, resumed in September 2020.[62]

Commemoration

The birthdate of Montaigne served as the basis to establish National Essay Day in the United States.

The humanities branch of the University of Bordeaux is named after him: Université Michel de Montaigne Bordeaux 3.[63]

References

- Foglia, Marc; Ferrari, Emiliano (18 August 2004). "Michel de Montaigne". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2019 ed.).

- Robert P. Amico, The Problem of the Criterion, Rowman & Littlefield, 1995, p. 42. Primary source: Montaigne, Essais, II, 12: "Pour juger des apparences que nous recevons des subjets, il nous faudroit un instrument judicatoire; pour verifier cet instrument, il nous y faut de la demonstration; pour verifier la demonstration, un instrument : nous voilà au rouet [To judge of the appearances that we receive of subjects, we had need have a judicatorie instrument: to verifie this instrument we should have demonstration; and to approve demonstration, an instrument; thus are we ever turning round]" (transl. by Charles Cotton).

- "Montaigne". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Reynolds, Francis J., ed. (1921). . Collier's New Encyclopedia. New York: P. F. Collier & Son Company.

- His anecdotes are 'casual' only in appearance; Montaigne writes: 'Neither my anecdotes nor my quotations are always employed simply as examples, for authority, or for ornament...They often carry, off the subject under discussion, the seed of a richer and more daring matter, and they resonate obliquely with a more delicate tone,' Michel de Montaigne, Essais, Pléiade, Paris (ed. A. Thibaudet) 1937, Bk. 1, ch. 40, p. 252 (tr. Charles Rosen)

- Sophie Jama, L’Histoire Juive de Montaigne [The Jewish History of Montaigne], Paris, Flammarion, 2001, p. 76.

- "His mother was a Jewish Protestant, his father a Catholic who achieved wide culture as well as a considerable fortune." Civilization, Kenneth Clark, (Harper & Row: 1969), p. 161.

- Winkler, Emil (1942). "Zeitschrift für Französische Sprache und Literatur".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Goitein, Denise R (2008). "Montaigne, Michel de". Encyclopaedia Judaica. The Gale Group. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- Introduction: Montaigne's Life and Times, in Apology for Raymond Sebond, By Michel de Montaigne (Roger Ariew), (Hackett: 2003), p. iv: "Michel de Montaigne was born in 1533 at the chateau de Montagine (about 30 miles east of Bordeaux), the son of Pierre Eyquem, Seigneur de Montaigne, and Antoinette de Louppes (or López), who came from a wealthy (originally Iberian) Jewish family".

- "...the family of Montaigne's mother, Antoinette de Louppes (López) of Toulouse, was of Spanish Jewish origin...." – The Complete Essays of Montaigne, translated by Donald M. Frame, "Introduction," p. vii ff., Stanford University Press, Stanford, 1989 ISBN 0804704864

- Popkin, Richard H (20 March 2003). The History of Scepticism: From Savonarola to Bayle. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0195107678.

- Green, Toby (17 March 2009). Inquisition: The Reign of Fear. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1429938532.

- Goitein, Denise R (2008). "Montaigne, Michel de". Encyclopaedia Judaica. The Gale Group. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- Montaigne. Essays, III, 13

- Bakewell, Sarah (2010). How to Live – or – A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer. London: Vintage. pp. 54–55. ISBN 9781446450901. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- Hutchins, Robert Maynard; Hazlitt, W. Carew, eds. (1952). The Essays of Michel Eyquem de Montaigne. Great Books of the Western World. Vol. twenty–five. Trans. Charles Cotton. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. v.

He had his son awakened each morning by 'the sound of a musical instrument'

- Philippe Desan (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Montaigne, Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 60.

- Bibliothèque d'humanisme et Renaissance: Travaux et documents, Volume 47, Librairie Droz, 1985, p. 406.

- Lowenthal, Marvin; de Montaigne, Michel (1999). The Autobiography of Michel de Montaigne. New Hampshire: Nonpareil Books. p. xxxii.

- Frame, Donald (translator). The Complete Essays of Montaigne. 1958. p. v.

- Kramer, Jane (31 August 2009). "Me, Myself, And I". The New Yorker. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- St. John, Bayle (16 March 2019). "Montaigne the essayist. A biography". London, Chapman and Hall. Retrieved 16 March 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- Bertr, Lauranne (27 February 2015). "Léonor de Montaigne – MONLOE : MONtaigne à L'Œuvre". Montaigne.univ-tours.fr. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Kurz, Harry (June 1950). "Montaigne and la Boétie in the Chapter on Friendship". PMLA. 65 (4): 483–530. doi:10.2307/459652. JSTOR 459652. S2CID 163176803. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- Bakewell, Sarah (2010). How to Live – or – A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer. London: Vintage. ISBN 9781446450901.

- As cited by Richard L. Regosin, ‘Montaigne and His Readers', in Denis Hollier (ed.) A New History of French Literature, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London 1995, pp. 248–252 [249]. The Latin original runs: 'An. Christi 1571 aet. 38, pridie cal. mart., die suo natali, Mich. Montanus, servitii aulici et munerum publicorum jamdudum pertaesus, dum se integer in doctarum virginum recessit sinus, ubi quietus et omnium securus (quan)tillum in tandem superabit decursi multa jam plus parte spatii: si modo fata sinunt exigat istas sedes et dulces latebras, avitasque, libertati suae, tranquillitatique, et otio consecravit.' as cited in Helmut Pfeiffer, 'Das Ich als Haushalt: Montaignes ökonomische Politik’, in Rudolf Behrens, Roland Galle (eds.) Historische Anthropologie und Literatur: Romanistische Beträge zu einem neuen Paradigma der Literaturwissenschaft, Königshausen und Neumann, Würzburg, 1995 pp. 69–90 [75]

- Desan, Philippe (2016). The Oxford Handbook of Montaigne. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-021533-0.

- Ward, Adolphus; Hume, Martin (2016). The Wars of Religion in Europe. Perennial Press. ISBN 9781531263188. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- Edward Chaney, The Evolution of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations since the Renaissance, 2nd ed. (London, 2000), p. 89.

- Cazeaux, Guillaume (2015). Montaigne et la coutume [Montaigne and the custom]. Milan: Mimésis. ISBN 978-8869760044. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015.

- Montaigne's Travel Journal, translated with an introduction by Donald M. Frame and a foreword by Guy Davenport, San Francisco, 1983

- Treccani.it, L'encicolpedia Italiana, Dizionario Biografico. Retrieved 10 August 2013

- Desan, Philippe (2016). The Oxford Handbook of Montaigne. p. 233.

- Montaigne, Michel de, Essays of Michel de Montaigne, tr. Charles Cotton, ed. William Carew Hazlitt, 1877, "The Life of Montaigne" in v. 1. n.p., Kindle edition.

- "The Autobiography of Michel De Montaigne", translated, introduced, and edited by Marvin Lowenthal, David R. Godine Publishing, p. 165

- "Biographical Note", Encyclopædia Britannica "Great Books of the Western World", Vol. 25, p. vi "Montaigne"

- Bakewell, Sarah. How to Live – or – A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer (2010), pp. 325–326, 365 n. 325.

- "Titi Lucretii Cari De rerum natura libri sex (Montaigne.1.4.4)". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- Bruce Silver (2002). "Montainge, Apology for Raymond Sebond: Happiness and the Poverty of Reason" (PDF). Midwest Studies in Philosophy XXVI. pp. 95–110.

- Bloom, Harold (1995). The Western Canon. Riverhead Books. ISBN 978-1573225144.

- Bakewell, Sarah (2010). How to Live – or – A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer. London: Vintage. p. 280. ISBN 978-0099485155.

- King, Brett; Viney, Wayne; Woody, William.A History of Psychology: Ideas and Context, 4th ed., Pearson Education, Inc. 2009, p. 112.

- Hall, Michael L. Montaigne's Uses of Classical Learning. "Journal of Education" 1997, Vol. 179 Issue 1, p. 61

- Ediger, Marlow. Influence of ten leading educators on American education.Education Vol. 118, Issue 2, p. 270

- Montaigne, Michel de (1966). Of the education of children. pp. 31–32.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Worley, Virginia. Painting With Impasto: Metaphors, Mirrors, and Reflective Regression in Montagne's 'Of the Education of Children.' Educational Theory, June 2012, Vol. 62 Issue 3, pp. 343–370.

- Friedrich, Hugo; Desan, Philippe (1991). Montaigne. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520072534.

- Friedrich & Desan 1991, p. 71.

- Billault, Alain (2002). "Plutarch's Lives". In Gerald N. Sandy (ed.). The Classical Heritage in France. BRILL. p. 226. ISBN 978-9004119161.

- Olivier, T. (1980). "Shakespeare and Montaigne: A Tendency of Thought". Theoria. 54: 43–59.

- Harmon, Alice (1942). "How Great Was Shakespeare's Debt to Montaigne?". PMLA. 57 (4): 988–1008. doi:10.2307/458873. JSTOR 458873. S2CID 164184860.

- Eliot, Thomas Stearns (1958). Introduction to Pascal's Essays. New York: E. P. Dutton and Co. p. viii.

- Quoted from Hazlitt's "On the Periodical Essayists" in Park, Roy, Hazlitt and the Spirit of the Age, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1971, pp. 172–173.

- Kinnaird, John, William Hazlitt: Critic of Power, Columbia University Press, 1978, p. 274.

- Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations, Chapter 3, "Schopenhauer as Educator", Cambridge University Press, 1988, p. 135

- Sainte-Beuve, "Montaigne", "Literary and Philosophical Essays", Ed. Charles W. Eliot, New York: P. F. Collier & Son, 1938.

- Dove, Richard, ed. (1992). German writers and politics 1918 - 1939. Warwick studies in the European humanities (1. publ ed.). Houndmills: MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-333-53262-1.

- Powys, John Cowper (1916). Suspended Judgments. New York: G.A. Shaw. pp. 17.

- Auerbach, Erich, Mimesis: Representations of Reality in Western Literature, Princeton UP, 1974, p. 311

- "French museum has 'probably' found remains of philosopher Michel de Montaigne". Japan Times. 21 November 2019.

- "'Mystery' endures in France over Montaigne tomb: archaeologist". France 24. 18 September 2020.

- brigoulet#utilisateurs (27 February 2019). "Bordeaux's humanist university". Université Bordeaux Montaigne. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

Further reading

- Sarah Bakewell (2010). How to Live — or — A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer. New York: Other Press.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1903). "Montaigne". Critical and Miscellaneous Essays: Volume V. The Works of Thomas Carlyle in Thirty Volumes. Vol. XXX. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons (published 1904). pp. 65–69.

- Donald M. Frame (1984) [1965]. Montaigne: A Biography. San Francisco: North Point Press. ISBN 0-86547-143-6

- Kuznicki, Jason (2008). "Montaigne, Michel de (1533–1592)". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). Montaigne, Michel (1533–1592). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 339–341. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n208. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Jean Lacouture. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade (2007). Album Montaigne (in French). Gallimard. ISBN 978-2070118298. OCLC 470899664..

- Marvin Lowenthal (1935). The Autobiography of Michel de Montaigne: Comprising the Life of the Wisest Man of his Times: his Childhood, Youth, and Prime; his Adventures in Love and Marriage, at Court, and in Office, War, Revolution, and Plague; his Travels at Home and Abroad; his Habits, Tastes, Whims, and Opinions. Composed, Prefaced, and Translated from the Essays, Letters, Travel Diary, Family Journal, etc., withholding no signal or curious detail. Houghton Mifflin. ASIN B000REYXQG.

- Michel de Montaigne; Charles Henry Conrad Wright (1914). Selections from Montaigne, ed. with notes, by C.H. Conrad Wright. Heath's modern language series. D.C. Heath & Co.

- Saintsbury, George (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). pp. 748–750.

- M. A. Screech (1991) [1983]. Montaigne and Melancholy: The Wisdom of the Essays. Penguin Books.

- Charlotte C. S. Thomas (2014). No greater monster nor miracle than myself. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0881464856.

- Stefan Zweig (2015) [1942] Montaigne. Translated by Will Stone. Pushkin Press. ISBN 978-1782271031

External links

- Works by Michel de Montaigne at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Michel de Montaigne at Internet Archive

- Works by Michel de Montaigne at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Essays, lightly edited for easier reading

- Facsimile and HTML versions of the 10 Volume Essays of Montaigne at the Online Library of Liberty

- Essays by Montaigne at Quotidiana.org

- The Charles Cotton translation of some of Montaigne's Essays:

- plain text version by Project Gutenberg

- Essays English audio by Librivox

- The complete, searchable text of the Villey-Saulnier edition from the ARFTL project at the University of Chicago (in French)

- Montaigne Studies at the University of Chicago

- Titi Lucretii Cari De rerum natura libri sex, published in Paris 1563, later owned and annotated by Montaigne, fully digitised in Cambridge Digital Library

- The Montaigne Library of Gilbert de Botton, digitised in Cambridge Digital Library

- The Essays of Michel de Montaigne Archived 2 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine eBook at The University of Adelaide, translator: Charles Cotton, editor: William Carew Hazlitt