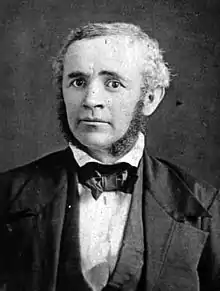

Michael Tuomey

Michael Tuomey (September 29, 1805 – March 30, 1857) was the State Geologist of South Carolina from 1844 to 1847, and the first State Geologist of Alabama, appointed in 1848 and serving until his death. His early descriptions and maps of the Birmingham District's unique coincidence of mineral resources for the making of steel opened the way for the early industrial development of the state.[1][2]

Biography

Michael was the son of Thomas and Nora (Foley) Tuomey of Cork, Ireland and was largely home-schooled in his youth. His natural talents as an observer combined with an interest in natural science led him to study biology.[1] He taught schools in England before emigrating to Somerset County, Maryland in the early 1830s. He farmed and served as a private tutor for a while, then entered the Rensselaer Institute at Troy, New York in 1835. There he discovered the emerging scientific field of geology and, though he graduated from the institute that same year, made it his life's study.[3]

Tuomey worked briefly as a field engineer for the railroads in North Carolina, then married the former Sarah E. Handy of Maryland in 1837 and returned to teaching, opening his own school in Petersburg, Virginia. On the recommendation of Sir Charles Lyell, he was appointed to succeed Edmund Ruffin as state geologist for South Carolina in 1844. After three years of work on that state's survey, he had become frustrated by the legislature's restrictions on his work. Lyell then recommended him to the state of Alabama where his interest in mineralogy rather than soils might be better rewarded. He still, however, emphasized the value of geological surveys to agriculture when making his reports.

Tuomey came to Tuscaloosa, Alabama in 1847, appointed a professor of geology, mineralogy and agricultural chemistry at the University of Alabama. He began his official surveys of the state's mineral resources, beginning with Red Mountain and Jones Valley in central Alabama, the next summer. His Geological Map of Alabama was printed in 1849 and his First Biennial Report of the Geology of Alabama was published by M. D. J. Slade in 1850.[3]

His report stated that:

It would be difficult to find a more striking illustration of the adaptation of the earth's surface to man's wants, produced by the simplest possible means. Had the underlying rocks remained in their original horizontal positions, the whole country between the Coosa and Tombigby would have been one monotonous sandstone plain. The coal would have been completely hidden, and no one could have even conjectured the existence of the inexhaustible beds of iron ore below the surface. But the simple pushing up of the Silurian rocks has revealed all these, in the most effectual and interesting manner, at the same time that it has intersected the coal measure with valleys of great fertility.[4]

In addition to his official maps and reports, Tuomey contributed numerous articles to the scientific literature and provided reports on his discoveries to the press. He also collected mineral and fossil specimens to the Alabama Museum of Natural History, many of which were lost when the campus was burned by Wilson's Raiders at the conclusion of the American Civil War.[5]

In 1854 Tuomey resigned his professorship to devote his full-time to the survey. He resumed teaching after his legislative appropriation expired in 1856.[3] He was a member of the Boston Society of Natural History and of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.[6] He was listed as one of the subscribers to the 1853 book Types of Mankind.[7]

His health failed in the Spring of 1857, and Mobile physician Josiah C. Nott diagnosed him with heart disease and pneumonia. He died on March 30, survived by his wife and two daughters, Margaret and Manora. His Second Biennial Report on the Geology of Alabama, edited by John Mallett, was published posthumously in 1858. He is buried in Tuscaloosa.[3] The University of Alabama's Tuomey Hall, built in 1888, was named in his honor.[8]

Publications

- Tuomey, Michael (1844) Geological and Agricultural Survey of South Carolina (Columbia)

- Tuomey, Michael (1848) Geology of South Carolina

- Tuomey, Michael (1849) Geological Map of Alabama

- Tuomey, Michael (1850) First Biennial Report on the Geology of Alabama (Tuscaloosa)

- Tuomey, Michael and Francis S. Holmes (1855-1857) Pleiocene Fossils of South Carolina (10 parts, Charleston)

- Tuomey, Michael (1858) Second Biennial Report on the Geology of Alabama, edited by John Mallett (Montgomery)

References

- Smith, Eugene Allen (October 1897) "Sketch of the Life of Michael Tuomey". American Geologist. Vol. 20, p. 207

- Kidd, Jessica Fordham (November 9, 2009) "Michael Tuomey". Encyclopedia of Alabama - accessed November 17, 2010

- Johnson, Rossiter, editor (1904) The Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans. Boston, Massachusetts: The Biographical Society

- Quoted in Fazio, Michael W. (2010) Landscape of Transformations: Architecture and Birmingham, Alabama. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press ISBN 978-1-57233-687-2

- Dean, Lewis S. (2001) The Papers of Michael Tuomey. Spartanburg, South Carolina: Reprint Company ISBN 0-87152-527-5

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1889). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- Types of Mankind (Philadelphia, 1853).

- "Tuomey Hall Renovation at UA Reveals 'Peep-Hole' Bookcase of Legendary Professor". University of Alabama News. April 22, 2002. Retrieved October 16, 2021.