Microneedle drug delivery

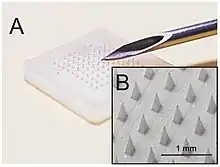

Microneedles or Microneedle patches or Microarray patches are micron-scaled medical devices used to administer vaccines, drugs, and other therapeutic agents.[2] While microneedles were initially explored for transdermal drug delivery applications, their use has been extended for the intraocular, vaginal, transungual, cardiac, vascular, gastrointestinal, and intracochlear delivery of drugs.[3][4][5] Microneedles are constructed through various methods, usually involving photolithographic processes or micromolding.[6] These methods involve etching microscopic structure into resin or silicon in order to cast microneedles. Microneedles are made from a variety of material ranging from silicon, titanium, stainless steel, and polymers.[7][1] Some microneedles are made of a drug to be delivered to the body but are shaped into a needle so they will penetrate the skin. The microneedles range in size, shape, and function but are all used as an alternative to other delivery methods like the conventional hypodermic needle or other injection apparatus.

Microneedles are usually applied through even single needle or small arrays. The arrays used are a collection of microneedles, ranging from only a few microneedles to several hundred, attached to an applicator, sometimes a patch or other solid stamping device. The arrays are applied to the skin of patients and are given time to allow for the effective administration of drugs. Microneedles are an easier method for physicians as they require less training to apply and because they are not as hazardous as other needles, making the administration of drugs to patients safer and less painful while also avoiding some of the drawbacks of using other forms of drug delivery, such as risk of infection, production of hazardous waste, or cost.

Background

Microneedles were first mentioned in a 1998 paper by the research group headed by Mark Prausnitz at the Georgia Institute of Technology that demonstrated that microneedles could penetrate the uppermost layer (stratum corneum) of the human skin and were therefore suitable for the transdermal delivery of therapeutic agents.[8] Subsequent research into microneedle drug delivery has explored the medical and cosmetic applications of this technology through its design. This early paper sought to explore the possibility of using microneedles in the future for vaccination. Since then researchers have studied microneedle delivery of insulin, vaccines, anti-inflammatories, and other pharmaceuticals. In dermatology, microneedles are used for scarring treatment with skin rollers.

The major goal of any microneedle design is to penetrate the skin's outermost layer, the stratum corneum (10-15μm).[9] Microneedles are long enough to cross the stratum corneum but not so long that they stimulate nerves which are located deeper in the tissues and therefore cause little to no pain.[8]

Research has shown that there is a limit on the type of drugs that can be delivered through intact skin. Only compounds with a relatively low molecular weight, like the common allergen nickel (130 Da),[10] can penetrate the skin. Compounds that weigh more than 500 Da cannot penetrate the skin.[9]

Types of microneedles

Since their conceptualization in 1998, several advances have been made in terms of the variety of types of microneedles that can be fabricated. The 5 main types of microneedles are solid, hollow, coated, dissolvable/dissolving, and hydrogel-forming.[2]

Solid

This type of array is designed as a two part system; the microneedle array is first applied to the skin to create microscopic wells just deep enough to penetrate the outermost layer of skin, and then the drug is applied via transdermal patch. Solid microneedles are already used by dermatologists in collagen induction therapy, a method which uses repeated puncturing of the skin with microneedles to induce the expression and deposition of the proteins collagen and elastin in the skin.[11]

Hollow

Hollow microneedles are similar to solid microneedles in material. They contain reservoirs that deliver the drug directly into the site. Since the delivery of the drug is dependent on the flow rate of the microneedle, there is a possibility that this type of array could become clogged by excessive swelling or flawed design.[9] This design also increases the likelihood of buckling under the pressure and therefore failing to deliver any drugs.

Coated

Just like solid microneedles, coated microneedles are usually designed from polymers or metals. In this method the drug is applied directly to the microneedle array instead of being applied through other patches or applicators. Coated microneedles are often covered in other surfactants or thickening agents to assure that the drug is delivered properly.[9] Some of the chemicals used on coated microneedles are known irritants. While there is risk of local inflammation to the area where the array was, the array can be removed immediately with no harm to the patient.

Dissolvable

In a more recent adaptation of the microneedle design, dissolvable microneedles encapsulate the drug in a nontoxic polymer which dissolves once inside the skin.[1] This polymer would allow the drug to be delivered into the skin and could be broken down once inside the body. Pharmaceutical companies and researchers have begun to study and implement polymers such as Fibroin, a silk-based protein that can be molded into structures like microneedles and dissolved once in the body.[12]

Hydrogel-forming

In hydrogel-forming microneedles, medications are enclosed in a polymer. The microneedles can penetrate the stratum corneum and draw up interstitial fluid leading to polymer swelling. Drugs enter the skin from the swollen matrix.

Advantages

There are many advantages to the use of microneedles, the most prominent being the improved comfort of patients. Needle phobia can affect both adults and children, and sometimes can lead to fainting. The benefit of microneedle arrays is that they reduce anxiety that patients have when confronted with a hypodermic needle. In addition to improving psychological and emotional comfort, microneedles have been shown to be substantially less painful than conventional injections.[9] Some studies recorded children's views on blood sampling with microneedles and found patients were more willing when prompted with a less painful procedure than traditional sampling with needles. Microneedles are beneficial to physicians as well, since they produce less hazardous waste than needles and are generally easier to use. Microneedles are also less expensive than needles as they require less material and the material used is cheaper than the materials in hypodermic needles.

Microneedles present a new opportunity for home and community-based healthcare. One of the biggest drawbacks of traditional needles is the hazardous waste that they produce, making disposal a serious concern for doctors and hospitals. For patients who require regular administration of medication at home, disposal can become an environmental concern is needles are placed in the trash. Dissolvable or swelling microneedles would provide those who are limited in their ability to seek hospital care with the ability to safely administer drugs in the comfort of their homes, although disposal of solid or hollow microneedles could still pose a needle-stick or blood borne pathogen infection risk.[1]

Another benefit of microneedles is their lower rates of microbial invasion into delivery sites.[1][9] Traditional injection methods can leave puncture wounds for up to 48 hours post-treatment. This leaves a large window of opportunity for harmful bacteria to enter into the skin. Microneedles only damage the skin to a depth of 10-15μm, making it difficult for bacteria to enter the bloodstream and giving the body a smaller wound to repair.[6] Further research is required to determine the types of bacteria able to breach the shallow puncture site of microneedles.

Disadvantages

There are some concerns about how physicians can be sure that all of the drug or vaccine has entered the skin when microneedles are applied. Hollow and coated microneedles both possess the risk that the drug will not properly enter the skin and will not be effective. Both of these types of microneedles can leak[13][9] onto a person's skin either by damage of the microneedle or incorrect application by the physician. This is why it is essential that physicians are trained how to properly apply the arrays.

Another concern is that incorrectly applied arrays could leave foreign material in the body. Although there is a lower risk of infection associated with microneedles, the arrays are more fragile than a typical hypodermic needle due to their small size and thus have a chance of breaking off and remaining in the skin. Some of the material used to construct the microneedles, such as titanium, cannot be absorbed by the body and any fragments of the needles would cause irritation.

There is a limited amount of literature available on the subject of microneedle drug delivery, as current research is still exploring how to make effective needles.

References

- McConville A, Hegarty C, Davis J (June 2018). "Mini-Review: Assessing the Potential Impact of Microneedle Technologies on Home Healthcare Applications". Medicines. 5 (2): 50. doi:10.3390/medicines5020050. PMC 6023334. PMID 29890643.

- Dharadhar S, Majumdar A, Dhoble S, Patravale V (February 2019). "Microneedles for transdermal drug delivery: a systematic review". Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy. 45 (2): 188–201. doi:10.1080/03639045.2018.1539497. PMID 30348022. S2CID 53039251.

- Panda A, Matadh VA, Suresh S, Shivakumar HN, Murthy SN (January 2022). "Non-dermal applications of microneedle drug delivery systems". Drug Delivery and Translational Research. 12 (1): 67–78. doi:10.1007/s13346-021-00922-9. PMID 33629222. S2CID 232047454.

- Thakur RR, Tekko IA, Al-Shammari F, Ali AA, McCarthy H, Donnelly RF (December 2016). "Rapidly dissolving polymeric microneedles for minimally invasive intraocular drug delivery". Drug Delivery and Translational Research. 6 (6): 800–815. doi:10.1007/s13346-016-0332-9. PMC 5097091. PMID 27709355.

- Peppi M, Marie A, Belline C, Borenstein JT (April 2018). "Intracochlear drug delivery systems: a novel approach whose time has come". Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 15 (4): 319–324. doi:10.1080/17425247.2018.1444026. PMID 29480039.

- Kim YC, Park JH, Prausnitz MR (November 2012). "Microneedles for drug and vaccine delivery". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 64 (14): 1547–1568. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2012.04.005. PMC 3419303. PMID 22575858.

- Park JH, Allen MG, Prausnitz MR (May 2005). "Biodegradable polymer microneedles: fabrication, mechanics and transdermal drug delivery". Journal of Controlled Release. 104 (1): 51–66. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.02.002. PMID 15866334.

- Henry S, McAllister DV, Allen MG, Prausnitz MR (August 1998). "Microfabricated microneedles: a novel approach to transdermal drug delivery". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 87 (8): 922–925. doi:10.1021/js980042+. PMID 9687334. S2CID 14917073.

- Jeong HR, Lee HS, Choi IJ, Park JH (January 2017). "Considerations in the use of microneedles: pain, convenience, anxiety and safety". Journal of Drug Targeting. 25 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1080/1061186x.2016.1200589. PMID 27282644. S2CID 44629532.

- Bos JD, Meinardi MM (June 2000). "The 500 Dalton rule for the skin penetration of chemical compounds and drugs". Experimental Dermatology. 9 (3): 165–169. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0625.2000.009003165.x. PMID 10839713.

- McCrudden MT, McAlister E, Courtenay AJ, González-Vázquez P, Singh TR, Donnelly RF (August 2015). "Microneedle applications in improving skin appearance". Experimental Dermatology. 24 (8): 561–566. doi:10.1111/exd.12723. PMID 25865925.

- Mottaghitalab F, Farokhi M, Shokrgozar MA, Atyabi F, Hosseinkhani H (May 2015). "Silk fibroin nanoparticle as a novel drug delivery system". Journal of Controlled Release. 206: 161–176. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.03.020. PMID 25797561.

- Rzhevskiy AS, Singh TR, Donnelly RF, Anissimov YG (January 2018). "Microneedles as the technique of drug delivery enhancement in diverse organs and tissues". Journal of Controlled Release. 270: 184–202. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.11.048. hdl:10072/376324. PMID 29203415. S2CID 205883540.

Further reading

- Ita K (2022). "Introduction". In Ita K (ed.). Microneedles. London: Academic Press. pp. 1–19. ISBN 978-0-323-97234-5.

External links

- Microneedles: a new way to deliver vaccines, Dawn Connelly, The Pharmaceutical Journal, 2021