Miguel Antonio Otero (born 1859)

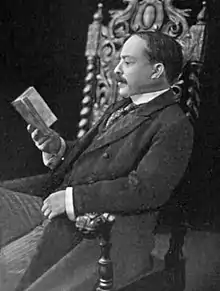

Miguel Antonio Otero II (October 17, 1859 – August 7, 1944) was an American politician, businessman, and author who served as the 16th Governor of New Mexico Territory from 1897 to 1906. He was the son of Miguel Antonio Otero, a prominent businessman and New Mexico politician.[1][2]

Miguel Antonio Otero | |

|---|---|

| |

| 15th Governor of New Mexico | |

| In office June 2, 1897 – January 10, 1906 | |

| Appointed by | William McKinley |

| Preceded by | William Taylor Thornton |

| Succeeded by | Herbert James Hagerman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 17, 1859 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | August 7, 1944 (aged 84) Santa Fe, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Education | Saint Louis University University of Notre Dame |

Early life

Miguel Antonio Otero had an adventurous boyhood as his father, a businessman and railroad baron, moved the family from town to town across Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico. The family established a permanent home in Las Vegas, New Mexico about 1879. He attended St. Louis University and the University of Notre Dame with his older brother Page, but preferred socializing to studying. He returned to Las Vegas in 1880 to work in his father's bank.

Career

Politics

While working as a banker, land broker, and livestock broke in Las Vegas, Otero began his career in politics. In a few years, he served as clerk for the City of Las Vegas, probate clerk of San Miguel County, county clerk, and recorder, and district court clerk for the Fourth Judicial District.[3] In 1892 he served as a delegate to the Republican National Convention and met Ohio Senator William McKinley. When McKinley was elected President in 1896, he appointed Otero governor of the Territory of New Mexico. Given Otero's youth (37 years), his meager statewide experience, and his lack of support from either political party, the appointment was somewhat of a surprise. The Otero name was well known in New Mexico, however, and initially he was supported by a wide range of constituencies.

As New Mexico moved towards statehood, Otero survived struggles against a variety of political factions in his own party. After McKinley's assassination, he survived a particularly brutal battle with Thomas B. Catron to earn reappointment by President Theodore Roosevelt. In 1899, he chartered the first secondary school in Santa Fe, Santa Fe High School. The infighting eventually took its toll, and in 1906, Roosevelt replaced Otero after more than eight years in the governor's mansion.

After leaving office, he returned to banking and mining before serving as state treasurer from 1909 to 1911. Otero attempted a comeback as governor in 1912, but failing to receive the Republican nomination and joined the Progressive Party. In later years he served on several commissions, including four years (1917 to 1921) as marshal of the Panama Canal.

Writing

In 1936, Otero published The Real Billy the Kid; With New Light on the Lincoln County War. After William Bonney was jailed in Las Vegas in 1880, Otero and his brother Page rode with the prisoner as he was transported by train from Las Vegas to Santa Fe. Remaining in Santa Fe for a while, the pair visited the Kid in jail many times, bringing him tobacco, gum, and sweets, and generally finding him a sympathetic, if misguided, figure. Written some fifty years after Pat Garrett's original account, Otero's was the first book to present Billy the Kid in a relatively positive light. The book was edited - some say ghost written - by Marshall Latham Bond whose father Hiram Bond was involved in trading with the Otero family out of Denver after 1872 and who owned a hundred square mile ranch in the area after the Lincoln County War.

Sandwiched around this book, Otero authored a three-part autobiography. The first installment, My Life on the Frontier, 1864–1882, was published in 1935 and covered the adventures of his youth through age 23, when his father died suddenly. My Life on the Frontier, 1882–1897 dealt with his early career in public service. My Nine Years as Governor of the Territory of New Mexico, 1897–1906 chronicles the turmoils of New Mexico on the verge of statehood.His writing is an early example of political autobiography, as his reflections are often a validation of his and his family's political choices. As a major proponent of New Mexico Statehood, Otero infuses the 3-volume autobiography with examples of how he helped "modernize" the territory and pave the way for statehood. [4]

The first book of the memoir is especially captivating, as Otero recalls several encounters with Western icons such as Kit Carson, Wild Bill Hickok, Gen. George Armstrong Custer, Doc Holliday, Bat Masterson, and Jesse James. Throughout these adventures, Otero casts himself as a civilizing force who learned from these wild westerners, but also brought more structured law, order, and economic advancement to the territory. [5]

Aids Earp posse

Otero is believed to have written a letter that described a portion of the Earp Vendetta Ride in 1882, when his father met the Earp posse in Albuquerque. Otero's presence in Albuquerque was corroborated by local newspapers.[6] According to the letter, Wyatt and Holliday were eating at The Retreat Restaurant in Albuquerque, owned by "Fat Charlie", "when Holliday said something about Earp becoming 'a damn Jew-boy.' Earp became angry and left…. [Henry] Jaffa told me later that Earp’s woman was a Jewess. Earp did mezuzah when entering the house." Wyatt was staying with a prominent businessman Henry N. Jaffa, who was also president of New Albuquerque’s Board of Trade. Jaffa was also Jewish, and based on the letter, Earp had while staying in Jaffa's home honored Jewish tradition by performing the mezuzah upon entering his home.[6]

According to Otero's letter, Jaffa told him that "Earp's woman was a Jewess." Earp's anger at Holliday's racial slur may indicate that the relationship between Josephine Marcus and Wyatt Earp was more serious at the time than is commonly known. The information in the letter is compelling because at the time it was written in the 1940s, the relationship between Wyatt Earp and Josephine Marcus while living in Tombstone was virtually unknown. The only way Otero could know these things was if he had a relationship with someone who had personal knowledge of the individuals involved.[6][7]

In popular culture

These locations were named after the Miguel Antonio Oteros.[8]

- Otero, New Mexico (ghost town in Colfax County), named in 1879.

- Otero County, Colorado, named in 1889.

- Otero County, New Mexico, named in 1899 while Miguel Antonio Otero (II) was territorial governor.

References

- "Biography of Governor Miguel Otero". History of New Mexico.

- Thompson, Mark. "Miguel Otero: Father, Son, and Grandson". History of New Mexico.

- Welsh, Cynthia (1992). "A "Star Will Be Added": Miguel Antonio Otero and the Struggle for Statehood". New Mexico Historical Review. 67 (1). Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- Murrah-Mandril, Erin (2020-04-01). In the Mean Time: Temporal Colonization and the Mexican American Literary Tradition. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 49–78. ISBN 978-1-4962-2173-5.

- Murrah, Erin (2008). "Miguel Antonio Otero: Destabilizing Identity in the West". Western American Literature. 43 (2): 129–147. doi:10.1353/wal.2008.0048. ISSN 1948-7142. S2CID 165623201.

- Hornung, Chuck; Gary L., Roberts (November 1, 2001). "The Split". TrueWestMagazine.com. True West. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- Singer, Saul Jay (September 24, 2015). "Wyatt Earp's Mezuzah". JewishPress.com. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- Otero, Miguel Antonio. My Life on the Frontier: 1864–1882 (Press of the Pioneers, 1935)

Bibliography

- Otero, Miguel Antonio. My Life on the Frontier, 1864–1882 (New York, 1935).

- Otero, Miguel Antonio. My Life on the Frontier, 1882–1897 (Albuquerque, 1939).

- Otero, Miguel Antonio. My Nine Years as Governor of New Mexico Territory (Albuquerque, 1940).

- Otero, Miguel Antonio. The Real Billy the Kid; With New Light on the Lincoln County War (1936).

}