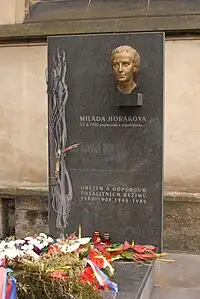

Milada Horáková

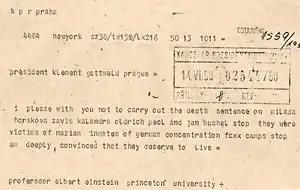

Milada Horáková (née Králová, 25 December 1901 – 27 June 1950) was a Czech politician and a member of the underground resistance movement during World War II. She was a victim of judicial murder, convicted and executed by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia on fabricated charges of conspiracy and treason.[2] Many prominent figures in the West, including Albert Einstein, Vincent Auriol, Eleanor Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, petitioned for her life.

Milada Horáková | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Milada Králová 25 December 1901 Prague, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 27 June 1950 (aged 48) Prague, Czechoslovak Socialist Republic |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Cause of death | Hanging |

| Political party | ČSNS |

| Children | Jana Kanská[1] |

| Alma mater | Charles University |

| Occupation | lawyer, politician |

| Awards | Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk Order of the White Double Cross |

She was executed at Prague's Pankrác Prison using a primitive variant of execution by hanging. She died after being strangled for more than 13 minutes.[3][4] Her remains were never found.[4]

Her conviction was annulled in 1968. She was fully rehabilitated in the 1990s and posthumously received the Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1st Class) and Order of the White Double Cross (1st Class).[5][6]

Early life

Dr Horáková was born Milada Králová in Prague. At the age of 17, in the last year of the First World War, she was expelled from school for participating in an anti-war demonstration. She completed her secondary education in the newly formed Czechoslovakia and studied law at Charles University, graduating in 1926. Her early political life was influenced by senator Františka Plamínková, the Women's National Council founder.

Horáková married her husband Bohuslav Horák in 1927. Their daughter, Jana, was born in 1933.

From 1927 to 1940, she was employed in the social welfare department of the Prague city authority. In addition to focusing on social justice issues, Horáková became a prominent campaigner for the equal status of women. She was also active in the Czechoslovak Red Cross.[7] In 1929 she joined the Czechoslovak National Social Party[8] which, despite the similarity in names, was a strong opponent of German National Socialism.

Wartime resistance

After the German occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1939, Horáková became active in the underground resistance movement. Together with her husband, she was arrested and interrogated by the Gestapo in 1940, in her case because of her pre-war political activity. She was sent to the ghetto at Terezín and then to various prisons in Germany.

In the summer of 1944, Horáková appeared before a court in Dresden. Although the prosecution demanded the death penalty, she was sentenced to 8 years imprisonment. She was released from detention in Bavaria in April 1945 by advancing United States forces in the closing stages of the Second World War.[9]

Political activity

Following the liberation of Czechoslovakia in 1945, Horáková returned to Prague and joined the leadership of the re-constituted Czechoslovak National Social Party. She became a member of the Provisional National Assembly. In 1946, she won a seat in the elected National Assembly representing the region of České Budějovice in southern Bohemia.

Her political activities again focused on enhancing the role of women in society and preserving Czechoslovakia's democratic institutions. Shortly after the Communist coup in February 1948, she resigned from the parliament in protest. Unlike many of her political associates, Horáková chose not to leave Czechoslovakia for the West, and continued to be politically active in Prague. On 27 September 1949, she was arrested and accused of being the leader of an alleged plot to overthrow the Communist regime.[3][8]

Trial and execution

Before facing trial, Horáková and her co-defendants were subjected to intensive interrogation by the StB, the Czechoslovak state security organ, using both physical and psychological torture. She was accused of leading a conspiracy to commit treason and espionage at the behest of the United States, Great Britain, France and Yugoslavia. Evidence of the alleged conspiracy included Horáková's presence at a meeting of political figures from the National Social, Social Democratic, and People's parties, in September 1948, held to discuss their response to the new political situation in Czechoslovakia. She was also accused of maintaining contacts with Czechoslovak political figures in exile in the West.[3]

The trial of Horáková and twelve of her colleagues began on 31 May 1950. It was intended to be a show trial, like those in the Soviet Great Purges of the 1930s. It was supervised by Soviet advisors and accompanied by a public campaign, organised by the Communist authorities, demanding the death penalty for the accused. The State's prosecutors were led by Dr. Josef Urválek and included Ludmila Brožová-Polednová.[10][11] The trial proceedings were carefully orchestrated with confessions of guilt secured from the accused.

A recording of the event, discovered in 2005, revealed Horáková's courageous defence of her political ideals. Invoking the values of Czechoslovakia's democratic presidents, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and Edvard Beneš, she declared that "no-one in this country should be put to death or be imprisoned for their beliefs."[12]

Milada Horáková was sentenced to death on 8 June 1950, along with three co-defendants (Jan Buchal, Oldřich Pecl, and Záviš Kalandra). Many prominent figures in the West, notably scientist Albert Einstein, former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, French President Vincent Auriol and former US First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, petitioned for her life, but the sentences were confirmed. Horáková was hanged in Prague's Pankrác Prison on 27 June 1950 at the age of 48.[3] Her reported last words were (in translation): "I have lost this fight but I leave with honour. I love this country, I love this nation, strive for their wellbeing. I depart without rancour towards you. I wish you, I wish you..."[13]

Following the execution, Horáková's body was cremated at Strašnice Crematorium, but her ashes were not returned to her family. Their whereabouts are unknown.

Other defendants

- Jan Buchal (1913–1950), State Security officer (executed)

- Vojtěch Dundr (1879–1957), former Secretary of the Czech Social Democratic Party (15 years)

- Dr. Jiří Hejda (1895–1985), former factory owner (life imprisonment)

- Dr. Bedřich Hostička (1914–1996), Secretary of the Czechoslovak People's Party (28 years)

- Záviš Kalandra (1902–1950), Marxist journalist (executed)

- Antonie Kleinerová (1901–1996), former member of Parliament for the Czechoslovak National Social Party (life imprisonment)

- Dr. Jiří Křížek (1895–1970), lawyer (22 years)

- Dr. Josef Nestával (1900–1976), administrator (life imprisonment)

- Dr. Oldřich Pecl (1903–1950), former mine owner (executed)

- Professor Dr. Zdeněk Peška (1900–1970), university professor (25 years)

- František Přeučil (1907–1996), publisher (life imprisonment)

- Fráňa Zemínová (1882–1962), editor and former member of Parliament for the Czechoslovak National Social Party (20 years)

Rehabilitations and honours

The trial verdict was annulled in June 1968 during the Prague Spring. The Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia that followed, and suppression of resistance, disrupted the process of her rehabilitation. Her rehabilitation was not completed until after the Velvet Revolution of 1989.

In 1990 a major thoroughfare in Prague 7, Letná, was renamed in her honour. In 1991 she was posthumously awarded the Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1st Class).[14] 27 June, the day of her execution, was declared "Commemoration Day for the Victims of the Communist Regime" in the Czech Republic.[9]

On 11 September 2008, aged 86, Ludmila Brožová-Polednová, the sole surviving member of the prosecution in the Horáková trial, was sentenced to six years in prison for assisting in the judicial murder of Milada Horáková. Brožová-Polednová was released from detention in December 2010, due to her age and health, and died on 15 January 2015.[11][15]

In January 2020 she was posthumously awarded the Order of the White Double Cross (1st Class) by Slovak president Zuzana Čaputová. Award was accepted by Erika Mačáková, member of Milada Horáková's Club. [16]

Family

Milada Horáková's husband, Bohuslav Horák, avoided arrest in 1949, escaping to West Germany and later settling in the United States. Their daughter, Jana, aged 16 at the time of her mother's execution, and subsequently raised by her aunt, was not able to join her father in the US until 1968, where she proceeded to have a family with three grandchildren.[1]

Horáková's last letters, including those to her husband and her daughter, have been published in English translation.[17]

Biographical film

Milada, a Czech-American feature film about the life of Milada Horáková, was released in November 2017. The role of Horáková is played by the Israeli-American actress Ayelet Zurer. The English-language production is directed by the Czech-born film-maker, David Mrnka, who also was one of the writers of the screenplay.[18]

See also

Notes

- Plavcová, Alena. "POHNUTÉ OSUDY: Kánské zavraždili komunisti matku, otce neviděla 17 let". Lidovky.cz. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- Lehovcová Suchá, Veronika (2 November 2007). "Eight years in prison for judicial murder from 1950". Aktuálně.cz.

- "Milada Horáková" Archived 27 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine Radio Praha (Accessed 14 November 2017)

- "Milada Horáková umírala čtvrt hodiny, zjistili historici". iDNES.cz. 29 June 2005. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Veľkým okamihom dnešnej ceremónie je rozhodnutie prezidentky vyznamenať Miladu Horákovú". DennikN. 2 January 2020.

- "Čaputová udelila štátne vyznamenania 20 osobnostiam. Pozrite si ich zoznam". hnonline.sk. 2 January 2020.

- "Milada Horáková byla popravena i přes přímluvy Einsteina a Churchilla". Reflex.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- "HORÁKOVÁ, Milada, roz. Králová (25. 1. 1901 Praha – 27. 6. 1950 Praha Pankrác) – Ústav pro studium totalitních režimů". www.ustrcr.cz. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- "JUDr. Milada Horáková". Valka.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- "Dr. Horáková Milada a spol. – Ústav pro studium totalitních režimů". www.ustrcr.cz. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- "Lubomír Boháč: Největší politický proces padesátých let před soudem | Listy". www.listy.cz. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- "Young director to bring story of Milada Horakova to silver screen". Radio Prague International. 6 April 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- Kaplan, Karel and Paleček, Pavel. Komunistický režim a politické procesy v Československu. Brno, 2001. p. 69

- Carey, Nick. "Milada Horakova" Radio Praha, 7 June 2000 (Accessed 18 November 2017)

- Lazarová, Daniela."Ludmila Brožová-Polednová, a former communist prosecutor who assisted in the notorious show trial against Milada Horáková has died at the age of 93." Radio Praha, 24 January 2015 (Accessed 23 November 2017)

- "Čaputová vyznamenala osobnosti, ktoré vzdorovali zlu, aj talenty vedy, umenia a športu" Denník Pravda, Bratislava, 18 January 2020

- "Women in World History, Primary Sources, Letters of Milada Horáková", George Mason University. (Accessed 20 November 2017) - Cited source: Iggers, Wilma A. Women of Prague: Ethnic Diversity and Social Change from the Eighteenth Century to the Present. Providence. 1995.

- Sladký, Pavel. Interview with David Mrnka, the director of Milada, Czech Film Center, 3 November 2017, published in Czech Film, Fall 2017 (Accessed 7 December 2017)

References

- Tazzer, Sergio (2008). Praga Tragica. Milada Horáková. 27 giugno 1950., Editrice Goriziana, Gorizia, 2008

- Margolius, Ivan (2006). Reflections of Prague: Journeys through the 20th century. Chichester: Wiley. ISBN 0-470-02219-1.

- Kaplan, Karel (1995). Nevětší politický proces M. Horáková a spol. Praha: Ústav pro soudobé dějiny AV ČR. ISBN 80-85270-48-X.

External links

- Milada Horáková – Czech in history, from archives of Czech Radio via radio.cz with RealAudio stream version.

- Martyr for freedom, washingtontimes.com

- I Shall Always Be With You - a letter by Milada Horáková to her daughter written on the eve of Horáková's execution Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, lettersofnote.com