Military of ancient Nubia

Nubia (/ˈnuːbiə, ˈnjuː-/) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt)[1][2] as well as the confluence of the blue and white Niles (south of Khartoum in central Sudan)[2] or, more strictly, Al Dabbah.[1][3] Nubia was the seat of several civilizations of ancient Africa, including the Kerma culture, the kingdom of Kush, Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia.

.jpg.webp)

The Kingdom of Kerma was the first great power in Nubia. Military organization centred on archery as the infantry was mostly equipped with swords, axes, clubs and shields. Weapons during this period were made of bronze. The people of Kerma also served as mercenaries in Ancient Egypt. The Kingdom of Kush, successor to Kerma, improved military organization and logistics in Nubia. Iron technology was introduced in Kush by the Assyrians after their conquest of Egypt. This allowed the manufacture of iron weapons such as swords, spears and armor in Nubia.

The role of the Cavalry was extensive during the meroitic period due to innovation in chariotry, the use of war elephants and cavalry tactics. Siege warfare was vastly developed with the creation of siege engines by the 8th century BC. Kush was succeeded by a number of Christian kingdoms after its collapse in the 4th century AD. The organization of the armies and navies of these kingdoms was largely based on that of their predecessor.

Kerma

.jpg.webp)

The Kerma culture was the first Nubian kingdom to unify much of the region. The Classic Kerma Culture, named for its royal capital at Kerma, was one of the earliest urban centers in the Nile region[5] Kerma culture was militaristic. This is attested by the many bronze daggers or swords as well as archer burials found in their graves.[6] Despite assimilation, the Nubian elite remained rebellious during Ancient Egyptian occupation. Numerous rebellions and military conflict occurred almost under every Ancient Egyptian reign until the 20th dynasty.[7] At one point, Kerma came very close to conquering Egypt as the Egyptians suffered a serious defeat by the natives of Kerma.[8][9]

Ta-Seti which means; "land of the bow" was the name used to refer to Nubia itself by the ancient Egyptians for their skills in archery.[10][11][12][13] Nubian tribes such as the Medjay served as mercenaries in Ancient Egypt.They also were sometimes employed as soldiers (as we know from the stele of Res and Ptahwer). During the Second Intermediate Period, they were even used in Kamose's campaign against the Hyksos[14] and became instrumental in making the Egyptian state into a military power.[15]

Kingdom of Kush

The Kingdom of Kush began to emerge around 1000 BC, 500 years after the end of the Kingdom of Kerma. By 1200 BC, Egyptian involvement in the Dongola Reach was nonexistent. By the 8th century BC, the new Kushite kingdom emerged from the Napata region of the upper Dongola Reach. The first Napatan king, Alara, dedicated his sister to the cult of Amun at the rebuilt Kawa temple, while temples were also rebuilt at Barkal and Kerma. A Kashta stele at Elephantine, places the Kushites on the Egyptian frontier by the mid-eighteenth century. This first period of the kingdom's history, the 'Napatan', was succeeded by the 'Meroitic period', when the royal cemeteries relocated to Meroë around 300 BC.[17]

War against Assyria

Kushite Kings conquered Egypt and formed the 25th dynasty, reigning in part or all of Ancient Egypt from 744 to 656 BC.[7] Taharqa began cultivating alliances with elements in Phoenicia and Philistia who were prepared to take a more independent position against Assyria.[18] Taharqa's army undertook successful military campaigns, as attested by the "list of conquered Asiatic principalities" from the Mut temple at Karnak and "conquered peoples and countries (Libyans, Shasu nomads, Phoenicians?, Khor in Palestine)" from Sanam temple inscriptions.[7] Torok mentions the military success was due to Taharqa's efforts to strengthen the army through daily training in long-distance running, as well as Assyria's preoccupation with Babylon and Elam.[7] Taharqa also built military settlements at the Semna and Buhen forts and the fortified site of Qasr Ibrim.[7]

Imperial ambitions of the Assyrian Empire as well as the growing influence of the 25th dynasty made war between them inevitable. In 701 BC, Taharqa and his army aided Judah and King Hezekiah in withstanding a siege by King Sennacherib of Assyria (2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9).[19] There are various theories (Taharqa's army,[20] disease, divine intervention, Hezekiah's surrender, Herodotus' mice theory) that try to explain as to why the Assyrians failed to take Jerusalem but withdrew to Assyria.[21] Many historians claim that Sennacherib was the overlord of Khor following the siege in 701 BC. Sennacherib's annals record Judah was forced into tribute after the siege.[22] However, this is contradicted by Khor's frequent utilization of an Egyptian system of weights for trade,[23] the 20 year cessation in Assyria's pattern (before 701 and after Sennacherib's death) of repeatedly invading Khor,[24] Khor paying tribute to Amun of Karnak in the first half of Taharqa's reign,[7] and Taharqa flouting Assyria's ban on Lebanese cedar exports to Egypt, while Taharqa was building his temple to amun at Kawa.[25]

In 679 BC, Sennacherib's successor, King Esarhaddon, campaigned into Khor and took a town loyal to Egypt. After destroying Sidon and forcing Tyre into tribute in 677-676 BC, Esarhaddon carried a fullscale invasion of Egypt in 674 BC. Taharqa and his army defeated the Assyrians outright in 674 BC, according to Babylonian records.[26] There are few Assyrian sources on the invasion. However, it ended in what some scholars have assumed was possibly one of Assyria's worst defeats.[27] In 672 BC, Taharqa brought reserve troops from Kush, as mentioned in rock inscriptions.[7] Taharqa's Egypt still held sway in Khor during this period as evidenced by Esarhaddon's 671 BC annal mentioning that Tyre's King Ba'lu had "put his trust upon his friend Taharqa", Ashkelon's alliance with Egypt, and Esarhaddon's inscription asking "if the Kushite-Egyptian forces 'plan and strive to wage war in any way' and if the Egyptian forces will defeat Esarhaddon at Ashkelon."[28] However, Taharqa was defeated in Egypt in 671 BC when Esarhaddon conquered Northern Egypt. He went on to capture Memphis, as well as impose tribute, before withrawing back to Assyria.[29] Although the Pharaoh Taharqa had escaped to the south, Esarhaddon captured the Pharaoh's family, including "Prince Nes-Anhuret" and the royal wives,"[7] which were sent to Assyria as hostages. Cuneiform tablets mention numerous horses and gold headdresses were taken back to Assyria.[7] In 669 BC, Taharqa reoccupied Memphis, as well as the Delta, and recommenced intrigues with the king of Tyre.[29] Taharqa intrigued in the affairs of Lower Egypt, and fanned numerous revolts.[30] Esarhaddon again led his army to Egypt and on his death in 668 BC, the command passed to Ashurbanipal. Ashurbanipal and the Assyrians again defeated Taharqa, advancing as far south as Thebes. However, direct Assyrian control was not established.[29] The rebellion was stopped and Ashurbanipal appointed as his vassal ruler in Egypt Necho I, who had been king of the city Sais. Necho's son, Psamtik I was educated at the Assyrian capital of Nineveh during Esarhaddon's reign.[31] As late as 665 BC, the vassal rulers of Sais, Mendes, and Pelusium were still making overtures to Taharqa in Kush.[7] The vassal's plot was uncovered by Ashurbanipal and all rebels but Necho of Sais were executed.[7]

War against Roman legions

Meroitic forces fought numerous battles against Rome, many successful. A peace treaty was eventually negotiuated between Augustus and Kushite diplomats, with Rome ceding a buffer strip along the southern border and exempting the Kushites from paying any tribute.

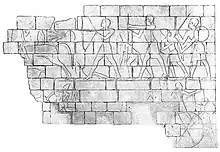

The Roman conquest of Egypt put it on a collision course with the Sudanic powers of the southern regions. In 25 BC, Kushites under their ruler Teriteqas, invaded Egypt with some 30,000 troops. Kushite forces were mostly infantry and their armament consisted of bows about 4 cubits long, shields of rawhide, clubs, hatchets, pikes and swords.[32]

The Kushites penetrated as far south as the Aswan area, defeating three Roman cohorts, conquering Syene, Elephantine and Philae, capturing thousands of Egyptians, and toppling bronze statutes of Augustus recently erected there. The head of one of these Augustian statutes was carried off to Meroe as a trophy, and buried under a temple threshold of the Kandake Amanirenas, to commemorate the Kushite victory, and symbolically tread on her enemies.[33][34][35] A year later, Rome dispatched troops under Gaius Petronius to confront the Kushites, with the Romans repulsing a poorly armed Meroitic force at Pselchis.[36] Strabo reports that Petronius continued to advance- taking Premnis and then the Kushite city of Napata.[37] Petronius deemed the roadless country unsuitable or too difficult for further operations. He pulled back to Premnis, strengthening its fortifications, and leaving a garrison in place.[38] These setbacks did not settle hostilities however, for a Kushite resurgence occurred just three years later under the queen or Kandake Amanirenas, with strong reinforcements of African troops from further south. Kushite pressure now once more advanced on Premnis. The Romans countered this initiative by sending more troops to reinforce the city.[39] Negotiations were held to end the conflict.[40]

The Meroitic diplomats were invited to confer with the Roman emperor Augustus himself on the Greek island of Samos where he was headquartered temporarily. The envoys of Meroe presented the Romans with a bundle of golden arrows and reputedly said: "The Candace sends you these arrows. If you want peace, they are a token of her friendship and warmth. If you want war, you are going to need them."[33] An entente between the two parties was beneficial to both. The Kushites were a regional power in their own right and resented paying tribute. The Romans sought a quiet southern border for their absolutely essential Egyptian grain supplies, without constant war commitments, and welcomed a friendly buffer state in a border region beset with raiding nomads. The Kushites too appear to have found nomads like the Blemmyes to be a problem, allowed Rome monitoring and staging outposts against them, and even conducted joint military operations with the Romans in later years against such mauraders.[41] The conditions were ripe for a deal. During negotiations, Augustus granted the Kushite envoys all they asked for, and also cancelled the tribute earlier demanded by Rome.[42] Premmis (Qasr Ibrim), and areas north of Qasr Ibrim in the southern portion of the "Thirty-Mile Strip"] were ceded to the Kushites, the Dodekaschoinos was established as a buffer zone, and Roman forces were pulled back to the old Greek Ptolemaic border at Maharraqa.[43] Roman emperor Augustus signed the treaty with the Kushites on Samos. The settlement bought Rome peace and quiet on its Egyptian frontier, and increased the prestige of Roman Emperor Augustus, demonstrating his skill and ability to broker peace without constant warfare, and do business with the distant Kushites, who a short time earlier had been fighting his troops. The respect accorded the emperor by the Kushite envoys as the treaty was signed also created a favorable impression with other foreign ambassadors present on Samos, including envoys from India, and strengthened Augustus' hand in upcoming negotiations with the powerful Parthians.[44] The settlement ushered in a period of peace between the two empires for around three centuries. Inscriptions erected by Queen Amanirenas on an ancient temple at Hamadab, south of Meroe, record the war and the favorable outcome from the Kushite perspective.[45] Along with his signature on the official treaty, Roman emperor Augustus marked the agreement by directing his administrators to collaborate with regional priests in the erection of a temple at Dendur, and inscriptions depict the emperor himself celebrating local deities.[46]

Christian Nubia

.jpg.webp)

The Arabs, who had taken over Egypt and large parts of the Middle east sought to conquer the region of Sudan. For almost 600 years, the powerful bowmen of the region created a barrier for Muslim expansion into the northeast of the African continent, fighting off multiple invasions and assaults. David Ayalon likened Nubian resistance to that of a dam, holding back the Muslim tide for several centuries.[47] According to Ayalon:

- The absolutely unambiguous evidence and unanimous agreement of the early Muslim sources is that the Arabs abrupt stop was caused solely and exclusively by the superb military resistance of the Christian Nubians. .. the Nubian Dam. The array of those early sources includes the two most important chronicles of early Islam, al-Tabari (d. 926) and al-Yaqubi (d. 905); the two best extant books on the Muslim conquests, al-Baladhuri (d. 892) and Ibn al-A tham al-Kufi (d. 926); the most central encyclopedic work of al-Masudi (d.956); and the two best early sources dedicated specifically to Egypt, Ibn Abd al-Hakim (d. 871) and al-Kindi (961).. All of the above-cited sources attribute Nubian success to their superb archery.. To this central factor should be added the combination of the Nubians' military prowess and Christian zeal; their acquaintance of the terrain; the narrowness of the front line that they had to defend; and, quite possibly, the series of cataracts situated at their back, and other natural obstacles.. The Nubians fought the Muslims very fiercely. When they encountered them they showered them with arrows, until all of them were wounded and they withdrew with many wounds and gouged eyes. Therefore they were called "the marksmen of the eye." [47]

Another historian notes:

- The awe and respect that the Muslims had for their Nubian adversaries are reflected in the fact that even a rather late Umayyad caliph, Umar b Abd al- Aziz (Umar II 717-720), is said to have ratified the Nubian-Muslim treaty out of fear for the safety of the Muslims (he ratified the peace treaty out of consideration for the Muslims and out of [a desire] to spare their lives..[48]

The Nubians constituted an "African front" that barred Islam's spread, along with others in Central Asia, India and the Anatolian/Mediterranean zone. Whereas the Islamic military expansion began with swift conquests across Byzantium, Central Asia, the Maghreb and Spain, such quick triumphs foundered at the Sudanic barrier.[49] Internal divisions, along with infiltration by nomads were to weaken the "Nubian dam" however, and eventually it gave way to Muslim expansion from Egypt and elsewhere in the region.[47]

Weapons and organization

Projectiles

Bowmen were the most important components in Kushite military.[50] Ancient sources indicate that Kushite archers favored one-piece bows that were between six and seven feet long, with a draw strength so powerful that many of the archers used their feet to bend their bows. However, composite bows were also used in their arsenal.[50] Greek historian, Herodotus indicated that primary bow construction was of seasoned palm wood, with arrows made of cane.[50] Kushite arrows were often poisoned-tipped.[51] Kushite archers were noted for their archery prowess by the Ancient Egyptians.[12] Cambyses ventured into Kush after conquering Egypt but logistical difficulties in crossing desert terrain were compounded by the fierce response of the Kushite armies, particularly accurate volleys of archery that not only decimated Persian ranks, but sometimes targeted the faces and eyes of individual Persian warriors.[50] One historical source notes:

- "So from the battlements as though on the walls of a citadel, the archers kept up with a continual discharge of well aimed shafts, so dense that the Persians had the sensation of a cloud descending upon them, especially when the Kushites made their enemies’ eyes the targets…so unerring was their aim that those who they pierced with their shafts rushed about wildly in the throngs with the arrows projecting from their eyes like double flutes."[50]

Two crossbow darts have been discovered at Qasr Ibrim.[52] One simple wooden self bow is known from an early Nobadian burial in Qustul.[53] The Nobadians shot barbed and possibly poisoned arrows of around 50 cm length.[54] To store the arrows, they used quivers made of tanned leather from long-necked animals such as goats or gazelles. Additionally, they were enhanced with straps, flaps and elaborate decoration.[55] The quivers were possibly worn on the front rather than on the back.[56] On the hand holding the bow, the archers wore bracelets to protect the hand from injuries while drawing the bowstring. For the nobility, the bracelets could be made of silver, while poorer versions were made of rawhide.[57] Furthermore, the archers wore thumb rings, measuring between three and four cm.[58] Thus, Nubian archers would have employed a drawing technique very similar to the Persian and Chinese ones, both of which were also reliant on thumb rings.[59] Mounted archery was prevalent in both the Meroitic and post-Meroitic periods.[60] Excavations at El-Kurru and studies of horse skeletons indicate the finest horses used in Kushite and Assyrian warfare were bred in and exported from Nubia.[7]

Siege weapons

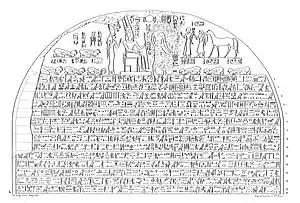

During the siege of Hermopolis in the 8th century BC, siege towers were built for the Kushite army led by Piye, in order to enhance the efficiency of Kushite archers.[61] After leaving Thebes, Piye's first objective was besieging Ashmunein. Following his army's lack of success he undertook the personal supervision of operations including the erection of a siege tower from which Kushite archers could fire down into the city.[62] Early shelters protecting sappers armed with poles trying to breach mud-brick ramparts gave way to Battering rams.[61] The use of the battering ram by Kushite forces against Egyptian cities are recorded on the stele of Piye;

Victory Stele of PiyeThen they fought against "The Peak, Chest of victories"...Then a battering ram was employed against it, so that its walls were demolished and a great slaughter made among them in incalculable numbers, including the son of the Chief of the Ma, Tefnakht....

— Victory Stele of Piye.[63]

Melee weapons

The Meroitic infantry attacking Rome consisted of shields of rawhide, clubs, hatchets, pikes and swords.[32]

A weapon characteristic of the Nobadians was a type of short sword.[64] It has a straight hollow-ground blade which was sharpened only on one edge and was therefore not designed to thrust, but to hack.[65] Apart from said swords, there were also lances, some of them with large blades, as well as halberds. The large-bladed lances and the halberds could have possibly been only ceremonial.[66]

Other war equipment

._Pyramidengruppe_A._Pyr._31._Pylon_(NYPL_b14291191-44197).jpg.webp)

The forces of Kerma wore no armor. However, Chariots as well as armory were manufactured in Kush during the Meroitic period.[67] Nobadian warriors and their leadership made use of shields and body armor, mostly manufactured from leather.[64][65] Fragments of thick hide have been found in the royal tombs of Qustul, suggesting that the principal interment was usually buried while wearing armor.[68] A well-preserved and richly decorated breastplate made of oxhide comes from Qasr Ibrim,[65] while a comparable, but more fragmentary piece was discovered at Gebel Adda. However, this breastplate was made of reptile hide, possibly from a crocodile.[69] Another fragment which possibly once constituted body armor comes from Qustul. It consists of several layers of tanned leather and was studded with lead rosettes.[64]

Elephants were occasionally used in warfare during the Meroitic period as seen in the war against Rome around 20 BC.[51] There is some debate about the purpose of the Great Enclosure at Musawwarat es-Sufra, with earlier suggestions including an elephant-training camp.[70] Taharqa built military settlements at the Semna and Buhen forts as well as the fortified site of Qasr Ibrim.[7] There is archaeological evidence for the Kushite fortification of Kalabsha, under the reign of Yesebokheamani presumably as a defence against the raiding Blemmyes.[71][72]

Navy

Not much is known about the naval forces of the various Nubian kingdoms. Most sources of Naval conflicts come from stelas and inscriptions. It is stated from the Piye stela that Piye led a naval fleet during an invasion of a harbor in Memphis, where he brought back with him to Kush as a spoil of war; several boats, ferry, pleasure boats and warships.[73] Also from the Stela, Piye defeated and captured many ships belonging to the Navy of lower Egypt in a sea battle.[74][75] According to archaeologist Pearce Paul Creasman, ships were essential in Piye's conquest of Egypt.[76]

Nastasen defeated an invasion of Kush from Upper Egypt. Nastasen's monument calls the leader of this invasion Kambasuten, a likely local variation of Khabbash. Khabbash was a local ruler of Upper Egypt who had campaigned against the Persians around 338 BC. His invasion of Kush was a failure, and Nastasen claimed to have taken many fine boats and other prizes of war during his victory.[77]

See also

References

- Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis (2005). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517055-9.

- Janice Kamrin; Adela Oppenheim. "The Land of Nubia". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-07-31.

- Raue, Dietrich (2019-06-04). Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-042038-8.

- "Jebel Barkal guide" (PDF): 97–98.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hafsaas-Tsakos, Henriette (2009). "The Kingdom of Kush: An African Centre on the Periphery of the Bronze Age World System". Norwegian Archaeological Review. 42 (1): 50–70. doi:10.1080/00293650902978590. S2CID 154430884. Retrieved 2016-06-08.

- O'Connor, David (1993). Ancient Nubia: Egypt's Rival in Africa. University of Pennsylvania, USA: University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania. pp. 1–112. ISBN 09-24-17128-6.

- Török, László (1998). The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Leiden: Brill. pp. 132–133, 153–184. ISBN 90-04-10448-8.

- Tomb Reveals Ancient Egypt's Humiliating Secret The Times (London, 2003)

- "Elkab's hidden treasure". Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 2009-02-15.

- Ancient Nubia: A-Group 3800–3100 BC

- The Fitzwilliam Museum: Kemet

- Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York: Institute for the study of the ancient world. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-615-48102-9.

- Newton, Steven H. (1993). "An Updated Working Chronology of Predynastic and Archaic Kemet". Journal of Black Studies. 23 (3): 403–415. doi:10.1177/002193479302300308. JSTOR 2784576. S2CID 144479624.

- Shaw 2000, p. 190.

- Steindorff & Seele 1957, p. 28.

- Elshazly, Hesham. "Kerma and the royal cache".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Edwards, David (2004). The Nubian Past. Oxon: Routledge. pp. 2, 75, 112, 114–117, 120. ISBN 9780415369886.

- Coogan, Michael David; Coogan, Michael D. (2001). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-19-513937-2.

- Aubin 2002, pp. x, 141–144.

- Aubin 2002, pp. x, 127, 129–130, 139–152.

- Aubin 2002, pp. x, 119.

- Roux, Georges (1992). Ancient Iraq (Third ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-012523-X.

- Aubin 2002, pp. x, 155–156.

- Aubin 2002, pp. x, 152–153.

- Aubin 2002, pp. x, 155.

- Aubin 2002, pp. x, 158–161.

- Ephʿal 2005, p. 99.

- Aubin 2002, pp. x, 159–161.

- Welsby, Derek A. (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. p. 158. ISBN 071410986X.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (2014-07-17). Egyptian Literature (Routledge Revivals): Vol. II: Annals of Nubian Kings. Routledge. ISBN 9781135078133.

- Mark 2009.

- O'Grady, Selina (2012). And Man Created God: A History of the World at the time of Jesus. pp. 79–88. See also Strabo, Geographia, Book XVII, Chaps 1 -3. Translated from Greek by W. Falconer (1903)

- O'Grady 2012, pp. 79–88.

- MacGregor, Neil (2011). A History of the World in 100 Objects. New York: Viking. pp. 221–226. ISBN 9780670022700.

- Shillington, Kevin (2012). History of Africa. London: Palgrave. p. 54. ISBN 9780230308473.

- Strabo, Geographica

- Derek A. Welsby. 1998. The Kingdom of Kush: The Napatan and Meroitic Empires.

- Strabo, Geographia, Book XVII, Chaps 1 -3

- Robert B. Jackson. 2002. At Empire's Edge: Exploring Rome's Egyptian Frontier. p. 140-156

- Fluehr-Lobban, RHodes et al. (2004) Race and identity in the Nile Valley: ancient and modern perspectives. p 55

- Richard Lobban 2004. Historical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Nubia, 2004. p70-78

- Jackson, At Empire's Edge, p 149

- Jackson, At Empire's Edge p. 149

- Raoul McLaughlin, 2014. The ROman Empire and the Indian Ocean. p61-72

- McLaughlin, The Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean 61-72

- Robert Bianchi, 2004. Daily Life of the Nubians, p. 262

- David Ayalon (2000) The Spread of Islam and the Nubian Dam. pp. 17-28. in Hagai Erlikh, I. Gershoni. 2003. The Nile: Histories, Cultures, Myths. 2000.

- "Views from Arab scholars and Merchants" Jay Spaulding and Nehemia Levtzion, IN Medieval West Africa: Views From Arab Scholars and Merchants, 2003.

- Ayalon, The Nubian Dam.

- Jim Hamm. 2000. The Traditional Bowyer's Bible, Volume 3, pp. 138-152

- David Nicolle, Angus McBride. 1991. Rome's Enemies 5: The Desert Frontier. p. 11-15

- Adams 2013, p. 138.

- Williams 1991, p. 84.

- Williams 1991, p. 77.

- Williams 1991, p. 78.

- Zielinski 2015, p. 801.

- Zielinski 2015, p. 795.

- Zielinski 2015, p. 798.

- Zielinski 2015, p. 798-899.

- Zielinski 2015, p. 794.

- "Siege warfare in ancient Egypt". Tour Egypt. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Dodson, Aidan (1996). Monarchs of the nile. Vol. 1. American Univ in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-97-74-24600-5.

- The Literature Of Ancient Egypt (in Arabic). pp. 374ff.

- Williams 1991, p. 87.

- Welsby 2002, p. 80.

- Welsby 2002, p. 79.

- Robert Morkot. Historical dictionary of ancient Egyptian warfare. Rowman & Littlefield, 2003, p. 26, xlvi

- Welsby 2002, p. 80-81.

- Hubert & Edwards 2010, p. 87.

- UNESCO Nomination document p.43.

- Plumley 1966.

- Török, László (1998). "276. Yesebokheamani; 277. Meroitic Dedication of Yesebokheamani". In Tormod Eide; Tomas Hägg; Richard Holton Pierce; László Török (eds.). Fontes Historiae Nubiorum. Textual Sources for the History of the Middle Nile Region between the Eighth Century BC and the Sixth Century AD. Vol III: From the First to the Sixth Century AD. Bergen: Institutt for klassisk filologi. pp. 1049–1051.

- The Literature Of Ancient Egypt (in Arabic). pp. 380ff.

- The Literature Of Ancient Egypt (in Arabic). pp. 372ff.

- Dodson, Aidan (1996). Monarchs of the nile. Vol. 1. American Univ in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-97-74-24600-5.

- Paul Creasman, Pearce (2017). Pharaoh's Land and Beyond: Ancient Egypt and Its Neighbors. Oxford University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-01-90-22907-8.

- Fage & Oliver 1975, p. 225.

Bibliography

- Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York: Soho Press. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- Shaw, Ian (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280293-3.

- Steindorff, George; Seele, Keith C. (1957). When Egypt Ruled the East. University of Chicago Press.

- Ephʿal, Israel (2005). "Esarhaddon, Egypt, and Shubria: Politics and Propaganda". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. University of Chicago Press. 57 (1): 99–111. doi:10.1086/JCS40025994. S2CID 156663868.

- Mark, Joshua J. (2009). "Ashurbanipal". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Adams, William Y. (2013). Qasr Ibrim: The Ballana Phase. Egypt Exploration Society. ISBN 978-0856982163.

- Williams, Bruce Beyer (1991). Noubadian X-Group Remains from Royal Complexes in Cemeteries Q and 219 and from Private Cemeteries Q, R, V, W, B, J and M at Qustul and Ballana. The University of Chicago.

- Zielinski, Lukasz (2015). "New insights into Nubian archery". Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean. 24 (1): 791–801.

- Welsby, Derek (2002). The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia. Pagans, Christians and Muslims along the Middle Nile. The British Museum. ISBN 0714119474.

- Hubert, Reinhard; Edwards, David N. (2010). "Gebel Abba Cemetery One, 1963. Post-medieval reuse of X-Group tumuli". Sudan&Nubia. 14: 83–90.

- Plumley, J. M. (1966). "Qasr Ibrim 1966". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 52: 9–12. doi:10.2307/3855813. JSTOR 3855813.

- Fage, J.D.; Oliver, Roland (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa Volume 2: From C.500 BC to AD1050. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-21592-7.