Military sexual trauma

As defined by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, military sexual trauma (MST) are experiences of sexual assault, or repeated threatening sexual harassment that occurred while a person was in the United States Armed Forces.

Use and definition

Military sexual trauma is used by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and defined in federal law[2] as "psychological trauma, which in the judgment of a VA mental health professional, resulted from a physical assault of a sexual nature, battery of a sexual nature, or sexual harassment which occurred while the Veteran was serving on active duty, active duty for training, or inactive duty training".[3] MST also includes military sexual assault (MSA) and military sexual harassment (MSH).[4] MST is not a clinical diagnosis. It is an identifier that labels the particular circumstances a survivor incurred during their sexual assault or sexual harassment.

Sexual harassment "... means repeated, unsolicited verbal or physical contact of a sexual nature which is threatening in character".[5][3] The behavior may include physical force, threats of negative consequences, implied promotion, promises of favored treatment, or intoxication of either the perpetrator or the victim or both.

Sexual assault

Military Sexual Assault (MSA) is a subset of MST that does not include sexual harassment.[6] MSA adversely affects thousands of service members during active military duty.[7] Gross et al. (2018) defines MSA as "[i]ntentional sexual contact characterized by the use of force, threats, intimidation, or abuse of authority or when the victim does not or cannot consent that has occurred at any point during active-duty military."[8]

MSA frequently causes survivors—both men and women—to develop mental disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders, and depressive disorders.[8][9] PTSD is a mental health diagnosis that can occur after a traumatic event including combat. Factors related to higher risk of MSA are; "younger age, enlisted rank, being nonmarried, and low educational achievement".[10] 15–49% of women and 1.5–22.5% of men experience sexual trauma prior to military service which has been shown to increase one's risk of sexual assault later on. MSA occurs more often in sexual and gender minorities.[6] MSA occurs within an institution which may perpetuate trauma symptoms.

Institutional betrayal

Survivors of MSA often work alongside their perpetrators which accounts for the institutional betrayal that survivors experience in the military.[9][10] Institutional betrayal is defined as "an organization's action (or inactions) are complicit in a person's trauma, especially when the traumatized person depends on the institution".[9][10] Institutional betrayal can occur to anyone who trusts or depends on an organization. Distrust among service members can increase when finding out about another person's MSA.[9] Research suggests that female veterans are less likely to trust their institution after MSA than male veterans.[9] MSA has been shown to occur more in the Navy and Marines than in other branches of the military.[9]

For survivors of MSA, the experience of institutional betrayal was found to negatively affect willingness to utilize Veterans Health Administration (VHA) medical and mental health care.[11] Institutional betrayal was additionally found to impact the type of health care sought by survivors of MSA.[11] Despite the availability of free health care through VHA, non-VHA mental health care was found to be more preferable.[11][12]

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression

Research has shown that sexual assault can contribute to PTSD, substance use, and depression.[7] Experiencing MSA has been connected to developing PTSD and depression at a higher rate than if an individual does not experience MSA.[9] However, MSA is connected to PTSD in female and male veterans while depression just among female veterans.[13] MSA, in combinations with other military stressors, can cause mental health problems.[10] MSA in transgender veterans resulted in PTSD, depression, and personality disorders.[6]

Substance use disorder (SUD)

Female veterans who experience MST are at an increased risk for SUD.[14] The prevalence of AUD doubled in female veterans suffering from MST (10.2% positive for MST vs. 4.7% negative for MST).[14] Additionally, SUD commonly occurs alongside Posttraumatic Stress (PTS) and PTSD.[10] In female veterans, research shows that MSA survivors with high PTS symptomatology are more likely to report SUD. The increases in SUD diagnosis and MST calls for trauma-informed treatment.[14]

Male veterans

Sexual assault happens to men within the military as well: 3–12% of men have experienced MSA.[15] Men who experience sexual assault may have issues with reporting based on stigma.[7] Male veterans who experienced sexual assault were twice as likely to attempt suicide than male veterans who had not been sexually assaulted.[16] Research has shown that Iraqi/Afghanistan-era male veterans reporting MSA displayed higher negative functional and psychiatric outcomes.[16] Studies have also shown that MSA in male veterans did not result in significant problems with controlling violent behavior, incarceration, or lower social support.[16]

Female veterans

In females, harassment in the military is associated with higher rates of PTSD.[17] Research suggests that female veterans experience MSA more than male veterans,.[8] specifically that 9–41% of female veterans have experienced MSA.[15] For female veterans in Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom, MSA is a significant predictor of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). These female veterans all experienced combat and therefore MSA was not a significant predictor of PTSD whereas combat stress was.[17]

Gender and sexual minorities

Lesbian, gay, bisexual (LGB) veterans

LGB veterans are more likely to have PTSD symptoms than heterosexual individuals after being exposed to combat stress and other factors.[15] PTSD symptomatology, in LGB Veterans, is linked to depression and substance use.[10][15] LGB veterans report being victimized by discrimination and stigmatizing labels more often than non-LGB individuals.[18] Due to compounded identity-based stressors, LGB service members and veterans are also at higher risk for suicide attempts compared to civilians.[19] Having experienced MSA places LGB individuals in the military at an amplified risk for suicide, beyond civilians and those who have not experienced an MSA.[20] LGB veterans have a higher rate of lifetime sexual assault some of which can occur during military service. Research suggests that LGB veterans experience MSA at a higher rate than non-LGB veterans.[15] Gay and Bisexual male veterans are more likely to experience MSA than non-LGB male veterans.[15] There is a significantly higher rate of PTSD in LGB female veterans than non-LGB female veterans.

Regarding prevalence:

Transgender veterans

At this point, there is very little research done on MST and/or MSA with transgender veterans.[6] The Minority Stress Model has been used to explain the impact of MSA and other stressors on the mental health of transgender veterans. Minority stress refers to chronic stress experienced by individuals within a stigmatized group. Distal Minority Stressors have been defined as; "external events of prejudice and discrimination".[6] Whereas Proximal Minority Stressors have been defined as; "internal processes, such as feelings of stress, anxiety, and concern, regarding concealment of true gender identity".[6] Studies have found that MSA is associated with minority stress and should be processed with transgender veterans along with the trauma of MSA.[6]

Regarding prevalence:

Prevalence

Military sexual trauma is a serious issue faced by the United States armed forces. In 2012, 13,900 men and 12,100 women who were active duty service members reported unwanted sexual contact[21] while in 2016, 10,600 men and 9,600 women reported being sexually assaulted.[22] Further, there were 5,240 official reports of sexual assault involving service members as victims in 2016; however, it is estimated that 77% of service member sexual assaults go unreported.[22] More specifically, prevalence of MST among veterans returning from Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) in Iraq, was reported to be as high as 15.1% among females and 0.7% among males.[23] In a study conducted in 2014, 196 female veterans who had deployed to OIF and/or OEF were interviewed and 41% of them reported experiencing MST.[24] As a result of these and similar findings, 17 former service members filed a lawsuit in 2010 accusing the Department of Defense of allowing a military culture that fails to prevent rapes and sexual assaults.[21] According to the Department of Defense Task Force on Sexual Violence (2004)[23] perpetrators of sexual assault were often male, serving in the military, and knew the victim well.

Reporting

Currently, the U.S. military allows victims of MST to make either restricted or unrestricted reports of sexual assault. This two tier system includes restricted (anonymous) and unrestricted reporting. A restricted report, allows victims to receive access to counseling and medical resources without disclosing their assault to authorities or seeking litigation against the perpetrator(s). This is different from an unrestricted report which involves seeking criminal charges against the perpetrator, eliminating anonymity.[25] The restricted reporting option is meant to reduce negative social consequences suffered by MST survivors, increase MST reporting and in doing so improve the accuracy of information concerning MST prevalence.[23] According to the DOD Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military (2016)[22] in 2015, there were 4,584 Unrestricted Reports involving Service members as either victims or subjects and 1,900 Restricted Reports involving Service members as either victims or subjects. The Services do not investigate Restricted Reports and do not record the identities of alleged perpetrators.[22] Service members who experience MST are eligible for medical care, mental healthcare, legal services, and spiritual support related to MST through the VA.[25][22]

U.S. military members appear to fear repercussions, retaliation, and the stigma associated with reporting MST. The reasons service members do not report military sexual assaults include concerns about confidentiality, wanting to "move on", not wanting to seem "weak", fear about career repercussions, fear of stigmatization, and worry about retaliation by superiors and fellow service members.[25][22][26] Additionally, survivors of MST may believe that nothing will be done if they report a sexual assault, they may blame themselves, and/or they may fear for their reputation.[22][26]

Effects of stigma on reporting rates

Stigma is a significant deterrent to reporting MST. Many military service members do not report sexual abuse due to fear about not being believed, worry about career impact, fear of retribution, or because their victimization will be minimized with comments such as "suck it up".[27] Additionally, perceived stigma associated with seeking mental health treatment after experiencing MST affects reporting.[26] Service members often do not disclose any type of trauma (sexual assault or battlefield trauma) until asked specifically by a mental health professional due to mental health stigma, worry about career difficulties, or because they wish to preserve their masculine image.[28][25]

Additionally, reporting MST sometimes results in an individual being diagnosed with a personality disorder, resulting in a discharge other than honorable, and reducing access to benefits from the VA or state.[29] A diagnosis of a personality disorder also discounts or minimizes the credibility of the victim and may result in stigmatization by the civilian community. Many survivors of MST report that they experience rejection from the military and feel incompetent after an Unrestricted Report.[30]

Consequences of reporting

In spite of increased access to medical and mental health resources there are also important drawbacks to unrestricted reports of MST. MST survivors often report a loss of professional and personal identity. They are also at increased risk of re-traumatization and retaliation through the process of getting help. Service members may experience re-traumatization through blame, misdiagnosis, and being questioned about the validity of their experience.[22][29] Retaliation from reporting a sexual complaint may have distressing consequences for the victim and weakens the respectful culture of the military. Retaliation can refer to reprisal, ostracism, maltreatment or abusive behavior by co-workers, exclusion by peers, or disruption of their career. The Department of Defense Task Force on Sexual Violence (2004)[23] reported that unkind gossip was the most common problem that members experienced at work in response to a MST report. In 2015, 68% of survivors reported at least one negative experience associated with their report of sexual assault.[22] The Department of Defense Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military (2016)[22] indicates that approximately 61% of retaliation reports involved a man or multiple men as alleged retaliators, while nearly 27% of reports included multiple men and women as retaliators. The majority (73%) of retaliators were not the alleged perpetrator of the associated sexual assault or sexual harassment. More than half (58%) of the alleged retaliators were in the chain of command of the reporter, followed by peers, co-workers, friends, or family members of the reporter, or a superior not in the reporters chain of command. Infrequently (7%), the alleged sexual perpetrator was also the alleged retaliator.[22]

Of the members of the military, 85% are active duty and male. Although more men than women in the military experience sexual assault, a larger proportion of female victims report their assault to military authorities.[22] In 2004, of service members who said they reported their experiences, 33% of women and 28% of men were satisfied with the complaint outcome, meaning approximately two thirds of women and men were dissatisfied. Service members who felt satisfied with the outcome of their report indicated that the situation was corrected, the outcome of the report was explained to them, and some action was taken against the offender. Service members who were dissatisfied with the outcome reported that nothing was done about their complaint.[23] Since changes in reporting standards were implemented in 2012, military sexual assault reporting has increased significantly.[22] Since this change, most service members report instances of MST to their direct supervisor, another person in their chain of command, or the offender's supervisor, rather than to a military special office or civilian authority.[23]

Individuals who make a report and deny mental health evaluations could be given a dishonorable discharge for making false allegations. Therefore, victims are sent the message to "keep quiet and deal with it" rather than reporting the assault and possibly losing their career and military benefits. In fact, 23% of women and 15% of men reported that action was taken against them because of their complaint.[23] Additionally, according to an investigation by the Human Rights Watch in 2016,[29] many survivors reported they received more disciplinary notices, were seen as "troublemakers", assigned undesirable shift assignments, were intimidated by drill sergeants, were threatened by peers with comments such as "you got what you deserved", and were socially isolated and further assaulted due to fear of more retaliation after an initial report.

Psychological/physiological difficulties

General

Service members who experiences MST may experience increased emotional and physical distress as well as feelings of shame, hopelessness, and betrayal. Some of the psychological experiences of both male and female survivors include: depression, symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), mood disorders, dissociative reactions, isolation from others, and self-harm. Medical symptoms survivors have experienced include sexual difficulties, chronic pain, weight gain, gastrointestinal problems and eating disorders.[30][31][27][32] In 2017, a study found that MST increases the chances a female survivor will become a victim of Intimate partner violence (IPV).[33]

Sexual minorities

According to research, reports of MST have been shown to be higher among veteran populations compared to current active duty personnel and DoD estimates.[34] Specifically within the lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) veteran community, who are significantly more likely to have experienced military sexual assault (MSA) (32.7% of combined female and male veterans) than non-LGB veterans (16.4%).[15][35]

Individuals identifying as a sexual minority are at a greater risk for MSA, than their heterosexual counterparts (32% vs. 16.4%).[15] Suffering from MSA causes psychological effects on veterans, often identified as PTSD, depression, anxiety, and substance abuse.[15] The disparity between heterosexual and non-heterosexual individuals’ exposure to MSA creates a divide in likelihood of psychological effects. LGB veterans reported more likely to have PTSD after leaving the military (41.2% vs. non-LGB 29.8%).[15] Veterans identifying with a sexual minority have reported to suffer from depression at a higher percentage than their heterosexual counterparts (49.7% vs. 36.0%).[15] After enduring MSA, many victims experience feelings of shame and disgrace, causing individuals of sexual minorities who suffered MSA to project hatred inwards because of the norms placed upon them by the heterosexual society.[36] The military has released LGB people from the branches of service based on their sexual orientation. The military has prohibited, openly LGB individuals from enlisting in the military through the use of,“Don’t Ask, Don’t tell”.[37] According to “American Psychologist”, the creation of a negative sexual stigma regarding homosexuality in the military has caused aggression against sexual minorities.[37] The increased risk of sexual assault that LGB service members are exposed to causes victims to be more likely exposed to the physical post-MSA side effects, which includes weight gain, weight loss, and HIV.[36]

Interpersonal difficulties

MST is a significant predictor of interpersonal difficulties post-deployment.[38] Holland and colleagues (2015)[39] found that survivors who perceived greater logistical barriers to obtaining mental health care reported more symptoms of depression and PTSD. Particularly for women veterans, PTSD and suicide are major concerns.[25] Males experiencing MST are associated with greater PTSD symptom severity, greater depression symptom severity, higher suicidality, and higher outpatient mental health treatment.[16] In general, male veterans who report experiencing MST are younger, less likely to be currently married, more likely to be diagnosed with a mood disorder, and more likely to have experienced non-MST sexual abuse either as children or adults than military members who have not been victimized.[25][38][31] However, the strongest predictor of any of these negative mental health outcomes, for either gender, includes anticipating public stigma (i.e., worrying about being blamed for the assault).[39]

Treatment services

In 2004 the Department of Defense (DOD) launched a task force that identified that service members who had faced sexual assault and harassment while deployed were in need of specialized medical treatments.[40] As a result of these findings, the DOD created the Sexual Assault Prevention Response (US military)[40] and ignited efforts to prevent, educate, provide adequate medical care for survivors and accountability for perpetrators.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) provides medical and mental health services free of charge to enrolled veterans who report MST and has implemented universal screening for MST among all veterans receiving VA health care.[41]

The Military Sexual Trauma Movement (MSTM) advocates for legislative and social reforms that would offer greater protections and resources to veterans who have experience MST, such as extending state veterans benefits to veterans who received "bad paper" discharges as a consequence of reporting MST.[42] The MSTM also allows servicemembers to report sexual harassment and abuse online.[43]

Disability benefits

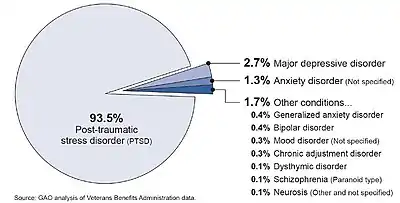

The Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA), a component of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), manages claims and the provision of disability benefits, including tax-free cash compensation, for veterans with service-connected injuries and disorders.[44][45]

Veterans who endured military sexual trauma are eligible for VA disability benefits if MST was "at least as likely as not" the cause of a mental disorder (or aggravated a pre-existing mental disorder).[46][47][48] A special provision in federal regulations lessens the burden of proof for veterans with MST-related posttraumatic stress disorder.[49]

A law that went into effect in January 2021[50] adds a new statute to the United States Code[51] that requires the Department of Veterans Affairs to "establish specialized teams to process claims for compensation for a covered mental health condition based on military sexual trauma", and specifically defines "a covered mental health condition" as "post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, or other mental health diagnosis described in the current version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders published by the American Psychiatric Association that the Secretary determines to be related to military sexual trauma."[52]

See also

References

- U.S. Gov't Accountability Off., GAO-14-477, Military Sexual Trauma: Improvements Made, but VA Can Do More to Track and Improve the Consistency of Disability Claim Decisions, p. 6, 2014.

- "Counseling and treatment for sexual trauma". 38 U.S.C. § 1720D(a)(1).

defining "sexual trauma"

. - Ritchie EC, Naclerio AL (2015). Women at war. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199344550.

- Lofgreen AM, Carroll KK, Dugan SA, Karnik NS (October 2017). "An Overview of Sexual Trauma in the U.S. Military". Focus. 15 (4): 411–419. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20170024. PMC 6519533. PMID 31975872.

- "38 U.S.C. § 1720D(f)".

- Beckman K, Shipherd J, Simpson T, Lehavot K (April 2018). "Military Sexual Assault in Transgender Veterans: Results From a Nationwide Survey". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 31 (2): 181–190. doi:10.1002/jts.22280. PMC 6709681. PMID 29603392.

- Castro CA, Kintzle S, Schuyler AC, Lucas CL, Warner CH (July 2015). "Sexual assault in the military". Current Psychiatry Reports. 17 (7): 54. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.640.2867. doi:10.1007/s11920-015-0596-7. PMID 25980511. S2CID 9264004.

- Gross GM, Cunningham KC, Moore DA, Naylor JC, Brancu M, Wagner HR, et al. (September 2018). "Does Deployment-Related Military Sexual Assault Interact with Combat Exposure to Predict Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Female Veterans?". Traumatology. May 2018: 66–71. doi:10.1037/trm0000165. PMC 6128291. PMID 30202245.

- Rabelo VC, Holland KJ, Cortina LM (2018-05-03). "From distrust to distress: Associations among military sexual assault, organizational trust, and occupational health". Psychology of Violence. 9: 78–87. doi:10.1037/vio0000166. ISSN 2152-081X. S2CID 149687371.

- Yalch MM, Hebenstreit CL, Maguen S (May 2018). "Influence of military sexual assault and other military stressors on substance use disorder and PTS symptomology in female military veterans". Addictive Behaviors. 80: 28–33. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.12.026. PMID 29310004.

- Monteith, Lindsey L.; Holliday, Ryan; Schneider, Alexandra L.; Miller, Christin N.; Bahraini, Nazanin H.; Forster, Jeri E. (2021-03-25). "Institutional betrayal and help-seeking among women survivors of military sexual trauma". Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 13 (7): 814–823. doi:10.1037/tra0001027. ISSN 1942-9681. PMID 33764096. S2CID 232354416.

- Holliday, Ryan; Monteith, Lindsey L. (2019-02-04). "Seeking help for the health sequelae of military sexual trauma: a theory-driven model of the role of institutional betrayal". Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 20 (3): 340–356. doi:10.1080/15299732.2019.1571888. ISSN 1529-9732. PMID 30714879. S2CID 73440956.

- Schuyler AC, Kintzle S, Lucas CL, Moore H, Castro CA (September 2017). "Military sexual assault (MSA) among veterans in Southern California: Associations with physical health, psychological health, and risk behaviors". Traumatology. 23 (3): 223–234. doi:10.1037/trm0000098. ISSN 1085-9373. S2CID 37251578.

- Goldberg SB, Livingston WS, Blais RK, Brignone E, Suo Y, Lehavot K, et al. (August 2019). "A positive screen for military sexual trauma is associated with greater risk for substance use disorders in women veterans". Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 33 (5): 477–483. doi:10.1037/adb0000486. PMC 6682420. PMID 31246067.

- Lucas CL, Goldbach JT, Mamey MR, Kintzle S, Castro CA (August 2018). "Military Sexual Assault as a Mediator of the Association Between Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Depression Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Veterans". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 31 (4): 613–619. doi:10.1002/jts.22308. PMID 30088291. S2CID 51935791.

- Schry AR, Hibberd R, Wagner HR, Turchik JA, Kimbrel NA, Wong M, et al. (Veterans Affairs Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center Workgroup) (November 2015). "Functional correlates of military sexual assault in male veterans". Psychological Services. 12 (4): 384–93. doi:10.1037/ser0000053. PMID 26524280. S2CID 7836320.

- Kearns JC, Gorman KR, Bovin MJ, Green JD, Rosen RC, Keane TM, Marx BP (December 2016). "The effect of military sexual assault, combat exposure, postbattle experiences, and general harassment on the development of PTSD and MDD in Female OEF/OIF veterans". Translational Issues in Psychological Science. 2 (4): 418–428. doi:10.1037/tps0000098. ISSN 2332-2179.

- Blosnich, J. R.; Gordon, A. J.; Fine, M. J. (2015). "Associations of sexual and gender minority status with health indicators, health risk factors, and social stressors in a national sample of young adults with military experience". Annals of Epidemiology. 25 (9): 661–667. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.06.001. PMID 26184439.

- Kimerling, R.; Makin-Byrd, K.; Louzon, S.; Ignacio, R. V.; McCarthy, J. F. (2016). "Military Sexual Trauma and Suicide Mortality". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 50 (6): 684–691. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.10.019. PMID 26699249.

- Kimerling, R.; Makin-Byrd, K.; Louzon, S.; Ignacio, R. V.; McCarthy, J. F. (2016). "Military Sexual Trauma and Suicide Mortality". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 50 (6): 684–691. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.10.019. PMID 26699249.

- "Active Duty Service Members Reporting Unwanted Sexual Contact" (PDF). Department of Defense. 2012.

- "Department of Defense Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military Fiscal Year 2015" (PDF). 2016.

- Department of Defense Task Force on Sexual Violence. (2004). "Sexual Harassment Survey of Reserve Component Members" (PDF).

- "Demographics. Profile of the Military Community" (PDF). Department of Defense. 2014.

- Conard PL, Young C, Hogan L, Armstrong ML (October 2014). "Encountering women veterans with military sexual trauma". Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 50 (4): 280–6. doi:10.1111/ppc.12055. PMID 24405124.

- Greene-Shortridge TM, Britt TW, Castro CA (February 2007). "The stigma of mental health problems in the military". Military Medicine. 172 (2): 157–61. doi:10.7205/milmed.172.2.157. PMID 17357770.

- Valente S, Wight C (March 2007). "Military sexual trauma: violence and sexual abuse". Military Medicine. 172 (3): 259–65. doi:10.7205/milmed.172.3.259. PMID 17436769.

- Brown NB, Bruce SE (May 2016). "Stigma, career worry, and mental illness symptomatology: Factors influencing treatment-seeking for Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom soldiers and veterans". Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy. 8 (3): 276–83. doi:10.1037/tra0000082. PMID 26390109.

- "Booted. Lack of Recourse for wrongfully discharged US military rape survivors" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. 2016.

- Northcut TB, Kienow A (September 2014). "The trauma trifecta of military sexual trauma: A case study illustrating the integration of mind and body in clinical work with survivors of MST". Clinical Social Work Journal. 42 (3): 247–59. doi:10.1007/s10615-014-0479-0. S2CID 144255750.

- "Military Sexual Trauma". U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for PTSD. 2015.

- Breland JY, Donalson R, Li Y, Hebenstreit CL, Goldstein LA, Maguen S (May 2018). "Military sexual trauma is associated with eating disorders, while combat exposure is not". Psychological Trauma. 10 (3): 276–281. doi:10.1037/tra0000276. PMC 6200455. PMID 28493727.

- Portnoy GA, Relyea MR, Street AE, Haskell SG, Iverson KM (May 2020). "A Longitudinal Analysis of Women Veterans' Partner Violence Perpetration: the Roles of Interpersonal Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms". Journal of Family Violence. 35 (4): 361–372. doi:10.1007/s10896-019-00061-3. ISSN 0885-7482. S2CID 163164420.

- Suris A, Lind L (October 2008). "Military sexual trauma: a review of prevalence and associated health consequences in veterans". Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 9 (4): 250–69. doi:10.1177/1524838008324419. PMID 18936282. S2CID 31772000.

- Wang J (2017). "Mental health and military service by sexual orientation among young Swiss men". European Journal of Public Health. 27 (suppl_3). doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckx187.047. ISSN 1101-1262.

- Bell ME, Turchik JA, Karpenko JA (February 2014). "Impact of gender on reactions to military sexual assault and harassment". Health & Social Work. 39 (1): 25–33. doi:10.1093/hsw/hlu004. PMID 24693601. S2CID 15158083.

- Burks DJ (October 2011). "Lesbian, gay, and bisexual victimization in the military: an unintended consequence of "Don't Ask, Don't Tell"?". The American Psychologist. 66 (7): 604–13. doi:10.1037/a0024609. PMID 21842972.

- Mondragon SA, Wang D, Pritchett L, Graham DP, Plasencia ML, Teng EJ (November 2015). "The influence of military sexual trauma on returning OEF/OIF male veterans". Psychological Services. 12 (4): 402–11. doi:10.1037/ser0000050. PMID 26524282.

- Holland KJ, Rabelo VC, Cortina LM (April 2016). "Collateral damage: Military sexual trauma and help-seeking barriers". Psychology of Violence. 6 (2): 253–261. doi:10.1037/a0039467.

- "CRS Reports". Congressional Research Service (CRS). Retrieved 2021-03-22.

- Veterans Health Admin., Dep't Veterans Aff., Top 10 Things All Healthcare & Service Professionals Should Know About VA Services for Survivors of Military Sexual Trauma.

- "Sexually harassed and labeled a 'liar,' now this Navy veteran is trying to heal". Connecting Vets. 2019-10-02. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- "Marine disciplined for urging people who opposed tanks at Trump's July 4th event to kill themselves". Task & Purpose. 2019-08-29. Archived from the original on 2019-12-24. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- "About VBA - Veterans Benefits Administration". va.gov. Retrieved 2020-01-29.

- Principles relating to service connection, 38 C.F.R. § 3.303 ("Service connection connotes many factors but basically it means that the facts, shown by evidence, establish that a particular injury or disease resulting in disability was incurred coincident with service in the Armed Forces, or if preexisting such service, was aggravated therein.")

- Benefit of the Doubt, 38 U.S.C. § 5107(b) ("... When there is an approximate balance of positive and negative evidence regarding any issue material to the determination of a matter, the Secretary shall give the benefit of the doubt to the claimant.").

- Gilbert v. Derwinski, 1 Vet. App. 49, 54 (1990) ("... when a veteran seeks benefits and the evidence is in relative equipoise, the law dictates that the veteran prevails.").

- Veterans Benefits Admin., Dep't Veterans Aff., M21-1 Adjudication Procedures Manual, pt. III, subpt. iv, chap. 5, sec. A, no. 1, subchap. j., Reasonable Doubt Rule ("The reasonable doubt rule means that the evidence provided by the claimant/beneficiary [or obtained on his/her behalf] must only persuade the decision maker that each factual matter is at least as likely as not...").

- Posttraumatic stress disorder, 38 C.F.R. § 3.304(f)(5).

- Johnny Isakson and David P. Roe, M.D. Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 2020, Pub. L. No. 116-315, 134 Stat. 4932.

- 38 U.S.C. 1166.

- Evaluation of Service-connection of Mental Health Conditions Relating to Military Sexual Trauma, Johnny Isakson and David P. Roe, M.D. Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 2020, Pub. L. No. 116-315, § 5501(a) (Jan. 5, 2021).

External links

- Military Sexual Trauma

- Uniform Betrayal: Rape in the Military Documentary produced by HealthyState.org (Health News from Florida Public Media)

- Stop military rape (site under construction)