Milnrow

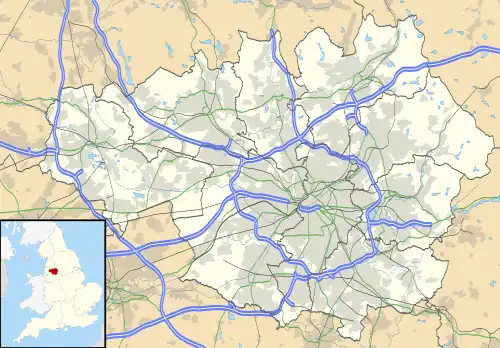

Milnrow is a town within the Metropolitan Borough of Rochdale, in Greater Manchester, England.[1][2][3] It lies on the River Beal at the foothills of the South Pennines, and forms a continuous urban area with Rochdale. It is 2 miles (3.2 km) east of Rochdale town centre, 10 miles (16.1 km) north-northeast of Manchester, and spans from Windy Hill in the east to the Rochdale Canal in the west. Milnrow is adjacent to junction 21 of the M62 motorway, and includes the village of Newhey, and hamlets at Tunshill and Ogden.

| Milnrow | |

|---|---|

Milnrow and the M62 motorway | |

Milnrow Location within Greater Manchester | |

| Population | 13,061 (2011 Census) |

| OS grid reference | SD926126 |

| • London | 168 mi (270 km) SSE |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | ROCHDALE |

| Postcode district | OL16 |

| Dialling code | 01706 |

| Police | Greater Manchester |

| Fire | Greater Manchester |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Historically in Lancashire, Milnrow during the Middle Ages was one of several hamlets in the township of Butterworth and parish of Rochdale. The settlement was named by the Anglo-Saxons, but the Norman conquest of England resulted in its ownership by minor Norman families, such as the Schofields and Cleggs. In the 15th century, their descendants successfully agitated for a chapel of ease by the banks of the River Beal, triggering its development as the main settlement in Butterworth. Milnrow was primarily used for marginal hill farming during the Middle Ages, and its population did not increase much until the dawn of the woollen trade in the 17th century.

With the development of packhorse routes to emerging woollen markets in Yorkshire, the inhabitants of Milnrow adopted the domestic system, supplementing their income by fellmongering and producing flannel in their weavers' cottages. Coal mining and metalworking also flourished in the Early Modern period, and the farmers, colliers and weavers formed a "close-knit population of independent-minded workers".[4] The hamlets of Butterworth coalesced around the commercial and ecclesiastical centre in Milnrow as demand for the area's flannel grew. In the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution supplanted domestic woollen industries and converted the area into a mill town, with cotton spinning as the principal industry. Mass-produced textile goods from Milnrow's cotton mills were exported globally with the arrival of the railway in 1863. The Milnrow Urban District was established in 1894 and was governed by the district council until its abolition in 1974.

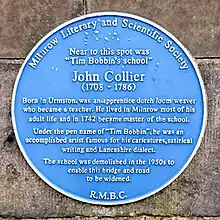

Deindustrialisation and suburbanisation occurred throughout the 20th century resulting in the loss of coal mining and cotton spinning. Milnrow was merged in to the Metropolitan Borough of Rochdale in 1974, and has since become suburban to Rochdale.[2] However, the area has retained "a distinct and separate character",[4] and has been described as "the centre of the south Lancashire dialect".[5] John Collier (who wrote under the pseudonym of Tim Bobbin) is acclaimed as an 18th-century caricaturist and satirical poet who produced Lancashire-dialect works during his time as Milnrow's schoolmaster. Rochdale-born poet Edwin Waugh was influenced by Collier's work, and wrote an extensive account of Milnrow during the mid-19th century in a tribute to him.[6] Milnrow has continued to grow in the 21st century, spurred by its connectivity to road, rail and motorway networks. Surviving weavers' cottages are among Milnrow's listed buildings, while the Ellenroad Steam Museum operates as an industrial heritage centre.

History

The earliest evidence of human activity comes from the Mesolithic peoples, who left thousands of flint tools on the moorland surrounding Milnrow.[7][8] A hunter-gatherer site was excavated by the Piethorne Brook in 1982, revealing a Mesolithic camp from which deer were hunted.[8] Neolithic activity is evidenced with a flint axe found at Newhey and a black stone axe found by Hollingworth Lake.[note 1][9][10] Excavations at Piethorne Reservoir in the mid-19th century combined with surveys during the 1990s revealed a spear-head (with a 5-inch (130 mm) blade) and ceramics respectively dated to Bronze Age Britain.[11][12] A Bronze-Age tumulus, funerary urn, and stone hammer or battle axe were discovered at Low Hill in 1879.[13][10] They imply the presence of Celtic Britons.[11][12] During the British Iron Age, this part of Britain was occupied by the Brigantes, but, despite ancient kilns used for dry ironstone smelting found at Tunshill,[14] it is unlikely that the tribe was attracted to the natural resources and landscape of the Milnrow area on a lasting basis.[15] Remains of a silver statue of the Roman goddess Victoria and Roman coins were discovered at Tunshill Farm in 1793,[16][17] and it is surmised that Romans traversed this area in communication with the Castleshaw Roman Fort.[15] Construction in the Victorian era is likely to have destroyed any other artifacts from the Stone Age, Bronze Age or Roman Britain.[18]

.jpg.webp)

The land was delineated during the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain.[19][20] It is theorised that this portion of the Manor of Rochdale was a seasonal enclosure for livestock farming and butter production, giving rise to the name Butterworth.[19] The Old English name is interpreted as meaning an "enclosed pastureland that provides good butter", using the suffix -worth typically applied to upland pastures in the South Pennines.[21] Butterworth was applied to a broad area, within which was Milnrow, which also has English toponymy implying Anglo-Saxon habitation.[22][1][23] The meaning of the name Milnrow may mean a "mill with a row of houses", combining the Old English elements myne and raw,[1] or myln and rāw,[23] or it may be a corruption of an old pronunciation of "Millner Howe", a water-driven corn mill at a place called Mill Hill on the River Beal that was mentioned in deeds dating from 1568.[24][25][26] Another explanation is that it is derived from a family with the name Milne, who owned a row of houses; a map from 1292 shows "Milnehouses" at Milnrow, other spellings have included "Mylnerowe" (1545) and "Milneraw" (1577).[25][26] Physical evidence of Anglo-Saxons or Norsemen comes from monastic inscribed stones—one of which has Latin text—discovered in 1986 at Lowhouse Farm.[22] The stones were dated to the Viking Age in the 9th-century.[22]

Seasonal farming practiced in Butterworth during the Early Middle Ages gave way to permanent settlements after the Norman conquest of England in 1066;[19] the Norman families of "de Butterworths", "de Turnaghs", "de Schofields", "de Birchinleghs", "de Wylds" and "Cleggs" were the new keepers of Butterworth,[25][27] in the hamlets of Belfield, Bleaked-gate-cum-Roughbank, Butterworth Hall, Clegg, Haughs, Lowhouse, Milnrow, Newhey, Ogden, Tunshill, and Wildhouse.[28] Records relating to these hamlets in the High Middle Ages are vague or incomplete, but show land was owned variously by the families, the Elland family, the Holland family, the Byron family, or the Knights Hospitaller.[29][30] The Byron family were endowed land in Milnrow during Norman times,[31] and their descendants include the Barons Byron in the peerage of England. In 1253, King Henry III granted rights to the Knights Hospitaller to conduct the trials of suspected thieves, regulate the production and sale of food using the Assize of Bread and Ale, and erect a gallows for public executions.[10][32] Butterworth had no church, it was part of the parish of Rochdale with ties to St Chad's Church in Rochdale.[33] The scattered community in and around Butterworth was primarily agricultural,[24][14] and centered on hill farming.[34] An oratory was licensed by the Bishop of Lichfield in 1400 for use as a chantry by the Byron family,[35] and a chapel of ease for the wider community followed in 1496.[10][35][36][37] A document dated 20 March 1496 from the reign of Henry VII, proclaims that open land by the River Beal at Milnrow would be the site of the new chapel, distinguishing it as a chapelry,[37] and prompting its development as the principal settlement.[25][27] Milnrow Chapel struggled to be viable, and depended on donations.[38] Interference from donors led to accusations of corruption and its confiscation by the Crown at the Dissolution of the Monasteries.[39][30]

Shallow coal mining was recorded at Milnrow in 1610,[10] while legal documents dated 1624 state that there were six cottages at Milnrow; with a further nine at Butterworth Hall, and three at Ogden.[40] Millstone Grit was the main building material of the time, used for dry stone farmhouses and field boundaries.[41] Milnrow stayed this way throughout the Late Middle Ages— its chapel appearing intermittently in records—[30] until woollen weaving was introduced.[42][43] Beginning as a subsidiary occupation, the carding, spinning, and handloom weaving of woollen cloth in the domestic system became the staple industry of Milnrow in the 17th century.[44][34] This was supported by the development of medieval trans-Pennine packhorse tracks, such as Rapes Highway routed from Milnrow to Marsden,[45][46] allowing access to woollen markets in Yorkshire and enabling commercial prosperity and expansion.[44] Fulling and textile bleaching was introduced,[10] and Milnrow became "especially known for fellmongering",[39] and "distinguished for its manufacture of flannels".[47] Demand for Milnrow flannel began to outstrip its supply of wool, resulting in imports from Ireland and the English Midlands.[42] An estimated 40,000–50,000 sheep hides were ordered every week,[48] and Milnrow's William Clegg Company established what was said to be the largest fellmongering yard in England.[39] Trade tokens were struck in Milnrow by local metalworkers to supplement a shortage of coins.[49] Sandstone was quarried in the late-17th century,[50] providing Milnrow with the material to extend the fully reinstated Milnrow Chapel in 1715,[39] as well as new three-storey "fine stone domestic workshops" or weavers' cottages during the 18th century.[42][51][52] These had dwelling quarters on the lower floors and loom-shops on the top floor.[42][51][52] Milnrow became a village of working class traders who used Rochdale as a central marketing and finishing hub;[42] the curate of Milnrow remarked that the gentry and yeomen classes had all left the area by 1800.[53] Road links to other markets were enhanced during the late-18th century,[54] culminating in an Act of Parliament passed in 1805 to create a turnpike from Newhey to Huddersfield.[55]

During surveys and excavations by Oxford Archaeology in the Kingsway Business Park, ten yeoman houses were identified dating to the seventeenth and early part of the eighteenth centuries. These included Moss Side Farm, Lower and Higher Moss Side Farms, Cherry Tree Farm, Lower Lane Farm, Pyche, Lane End and Castle Farm [56][57]

Middleton-born Radical writer Samuel Bamford wrote that at the beginning of the 19th century "such a thing as a cotton or woollen factory was not in existence" in Milnrow.[58] By 1815, three commercial manufacturers had established woollen mills in Milnrow.[34] while topographer James Butterworth wrote that Newhey consisted of "several ranges of cottages and two public houses" in 1828.[59] The Industrial Revolution introduced the factory system which was adopted by the local inhabitants; the River Beal was the main power source for new woollen weaving mills and technologies.[43] Construction of large mechanised cotton mills in nearby Oldham was admired by business owners in Milnrow, prompting them to build similar factories; the principal occupation remained as wool weaving, but cotton spinning and chainmaking was introduced.[43][60] Unusually for the period and region, women in particular were employed as chainmakers by Milnrow's blacksmiths during the 19th century.[34] Nationally, the factory system and the Corn Laws combined to reduce wages and increase food prices in the early-1840s, leading to protests and disorder at Milnrow in August 1842; the Riot Act was read and the 11th Hussars were deployed to restore order and protect burgeoning mills and their owners from harm.[61] The Corn Laws were repealed in 1846, and Ordnance Survey maps show Milnrow to have had three woollen mills, and one cotton mill by 1848.[39] The Oldham Corporation obtained compulsory purchase rights in 1858 to acquire and dam the Piethorne Brook, completing the Piethorne Reservoir in 1863.[62] The construction of rectangular multi-storey brick cotton mills followed,[63] and The British Trade Journal noted that cottages in Milnrow and Newhey were "in great demand".[64] Terraced houses with slate roofs and facades of stone or red brick were built in rows to house an influx of workers and families.[65] Streets and roads were cobbled, and transport was horse-drawn or by the Rochdale Canal.[66] The Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway opened the Oldham Loop railway line in 1863, with stations at Milnrow and Newhey—the latter gave rise to the "industrial village" of Newhey, with mills and housing built concentrically outwards from the railway line.[12] Butterworth Hall Colliery opened in 1865.[67] However, public street lighting was not widely available until after a dispute was heard by the House of Lords in April 1869.[68] Providers of gas lighting in the neighbouring Municipal Borough of Rochdale originally overlooked Milnrow because they had "not thought it worth their while extending their mains into a thinly populated district", but later conceded "there had been a great increase of population" and it was "thriving".[68] In the 1870s,[34] wool was supplanted by cotton "with success".[64] Ring spinning companies – some of the earliest in the UK – were formed by local influential businessmen, giving rise to Milnrow's reputation as a company town—the Heap business family exercised significant deferential and political influence upon the newly-formed Milnrow Local Board of Health from their Cliffe House home in Newhey.[69][70] Inspired by the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers, and using the Rochdale Principles, consumers' co-operative groups were established at Milnrow, Newhey, Ogden and Firgrove throughout the second half of the 19th century.[4] In 1885, municipal buildings were developed for the Milnrow Local Board, while an Act of Parliament empowered the Oldham Corporation to make further purchases in the Piethorne Valley so as to create additional reservoirs.[71] An elected urban district council was established for the "thriving town" of Milnrow and its hinterland in 1894,[3][39] followed by the introduction of new amenities: a golf course at Tunshill in 1901,[72] and a Carnegie library at Milnrow in 1907.[73] A steam-powered tram system connected to Rochdale was authorised for Milnrow in 1904, but was resisted—and later abandoned—by the district's "influential folk" who felt that "drawing the two communities closer" would result in "hastening the annexation" of Milnrow in to Rochdale.[39] Milnrow Council approved terms with Rochdale Corporation Tramways in 1909 for an electric-powered street-level passenger tramway running from Firgrove in the west to Newhey in the south.[74]

Cotton spinning was the principal industry in Milnrow in the 1910s—Newhey alone had ten cotton mills employing over 2,000 people at 1911,[39] while Butterworth Hall Colliery was the largest colliery in the Rochdale region, employing around 300 men in 1912.[75] These workers were able to travel Milnrow's completed tramway from 1912, which passed by Dale Street, Milnrow's central thoroughfare lined with banks, butchers, confectioners, chemists and drapers.[39] Ten years after it was first proposed, in 1913, a new Anglican parish church of St Ann was consecrated at Belfield at its boundary with Firgrove so as to serve the swell in population across the Rochdale-Milnrow boundary and ease pressure at Milnrow's Anglican parish church.[34] An outbreak of smallpox occurred in 1914; an investigation by the Royal Society of Medicine to link the infection with imported cotton bales from Brazil, Mexico, Peru or the United States was inconclusive.[76] The "most disastrous fire on record" in the Milnrow area resulted in the "spectacular" destruction of Newhey's Ellenroad Mill in 1916, at a cost of £150,000 (£10,820,000 in 2023),[77] but with no loss of life.[78] Tank Week, a national touring campaign to help fund the British heavy tanks of World War I, came to Milnrow resulting in a collective donation of £180,578 (£9,358,000 in 2023)[77] from the people of the district.[79] Upon conclusion of the war, the National Savings Movement praised the people of Milnrow for their donation, and in May 1919 presented the district with a 23-ton female Mark IV tank for permanent public display in Milnrow.[79] Butterworth Hall Colliery closed in 1928,[67] and poor maintenance forebode the closure of Milnrow's tramway in 1932.[39] In 1934, Milnrow Council agreed that its publicly displayed World War I tank had become "an eyesore" and "a potential source of danger to children", and consequently sold and removed it for scrap.[80][79] In the same year, Milnrow Council was gifted land in Firgrove to be used as a public sports pitch.[81] Social housing estates of semi-detached properties with gardens were constructed in both Milnrow and Newhey during the 1930s,[65] while roads in Newhey were laid by German prisoners of war during World War II.[66] Over 500 municipal homes were built between 1930 and 1950, which Chris Davies MP described in Parliament as "good, solid, middle-of-the-road housing [...] typical examples of some of the best council housing built in Britain".[82] Cliffe House at Newhey, formerly occupied by the prominent Heap manufacturing family, was demolished and in 1952 its grounds were opened as the recreational and publicly owned Milnrow Memorial Park.[70][83][84] Following the Great Depression, the region's textile sector experienced a decline until its eventual demise in the mid-20th century. Milnrow's last standing cotton mill was Butterworth Hall Mill, demolished in the late 1990s.[85] Milnrow experienced population growth and suburbanisation in the second half of the 20th century, spurred by the construction of the M62 motorway through the area, making Greater Manchester and West Yorkshire commutable.[43][86] The Pennine Drive housing estate was constructed in the mid-1980s.[52] A restoration project to reopen the dilapidated Rochdale Canal resulted in Firgrove Bridge, at Milnrow's boundary with Rochdale, being rebuilt in October 2001;[87][88] a Bellway-constructed housing estate was built next to the canal between 2005 and 2007.[89] Milnrow tram stop opened as part of Greater Manchester's light-rail Metrolink network on 28 February 2013.[90] Although its route through Milnrow was carefully planned to mitigate against bad weather conditions,[91] the local section of the M62 was made impassable by the "Beast from the East" cold weather wave in March 2018.[92][93] Stranded motorists were invited in to homes and offered food and shelter by "kindhearted" volunteers in Milnrow and Newhey while the British Army cleared the motorway.[92][93]

Governance

Lying within the historic county boundaries of Lancashire since the early 12th century, Milnrow was a component area of Butterworth, an ancient rural township within the parish of Rochdale and hundred of Salford.[3] Under feudalism, Butterworth was governed by a number of ruling families, including the Byrons, who would later be granted the title of Baron Byron, or Lord of the Manor of Rochdale.[37] The Knights Hospitaller held powers in Butterworth- by way of a grant from King Henry III of England in the 13th century, they were able to hold legal trials of suspected thieves, exercise the Assize of Bread and Ale, and perform public hangings.[39] Throughout the Late Middle Ages, local men acted as jurors and constables for the purposes of upholding law and order in Butterworth.[95] By 1825, there were several villages in Butterworth including Butterworth Hall, Haugh, Lady Houses, Little Clegg, Newhey, Ogden, Moorhouse, Schofield Hall and Milnrow itself, which was distinguished from the others as Butterworth's only chapelry.[96] Butterworth in the 19th century constituted a civil parish, until its dissolution in 1894.[3]

Milnrow's ratepayers rejected a proposal to create a local board of health—a tax-funded regulatory body responsible for standards of hygiene and sanitation—on 14 June 1869,[97] but a vote held on 17 December 1869 ended 546 to 466 in favour.[98] The Milnrow Local Board of Health, with jurisdiction over the wards of Belfield, Haugh and Milnrow,[40] was approved by central government on 2 February 1870 in accordance with the Local Government Act 1858.[3][99] Its 18 members convened for the first time on 18 August 1870,[39][100] and gave Milnrow its first measure of democratic self-governance.[39] James Heap, of the local Heap manufacturing family, was the first Chairman,[100] and the Heaps' influence on local politics gave rise to Milnrow's reputation as a company town.[69] In 1872, Milnrow Local Board of Health protested against proposals drawn by the Rochdale Corporation to combat water pollution in the River Roch and the River Beal, claiming that prohibiting the use of the Beal for its industrial and untreated human effluent would be "a sad blow to manufacturers and consequently to the working classes".[101] In 1879, the Firgrove part of the Castleton township and further parts of Butterworth township were incorporated into the jurisdiction of the local board.[3][96] Under the Local Government Act 1894, the area of the local board broadly became the Milnrow Urban District, a local government unit with elected councillors, in concord with the Rochdale Poor Law Union, and sharing power with Lancashire County Council as a constituent district of the administrative county of Lancashire.[3] Milnrow Urban District bordered the larger County Borough of Rochdale to the west, a politically independent authority which had been absorbing smaller neighbouring authorities—such as the Castleton Urban District in 1900 and the Norden Urban District in 1933—resulting in Milnrow people being "a little afraid of the borough and [...] annexation".[39] Under the Local Government Act 1972, the Milnrow Urban District was abolished, and Milnrow has, since 1 April 1974, formed an unparished area of the Metropolitan Borough of Rochdale, within the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester.[3] In anticipation of the new local government arrangement, Milnrow Urban District Council applied for successor parish status to be granted to the locality after 1974, but the application was not successful.[102]

From 1983 to 1997, Milnrow was represented in the House of Commons as part of the parliamentary constituency of Littleborough and Saddleworth. Between 1997 and 2010 it was within the boundaries of Oldham East and Saddleworth.[103] In 2010 Milnrow became part of the Rochdale constituency, which, as of 2017, is represented by Tony Lloyd MP, a member of the Labour Party. In 2010, The Guardian noted Milnrow as part of a "traditional heartland", where a "well of loyalty [for Labour] runs deep in the Pennine towns between Rochdale and Oldham",[104] while the 2002 Almanac of British Politics affirms Milnrow's residents "are willing to elect Liberal Democrat councillors".[105] Conservative clubs, Liberal clubs, and working men's clubs were established in Milnrow and Firgrove during the 19th and 20th centuries.[39]

Geography

At 53°36′36″N 2°6′40″W (53.6101°, −2.1111°), and 168 miles (270 km) north-northwest of central London, the centre of Milnrow stands roughly 492 feet (150 m) above sea level,[106] on the western slopes of the South Pennines, 10 miles (16.1 km) north-northeast of Manchester city centre. Blackstone Edge and Saddleworth are to the east; Rochdale and Shaw and Crompton are to the west and south respectively. Considered as the area covered by the former Milnrow Urban District, Milnrow extends over 8.1 square miles (21 km2), stretching from the Rochdale Canal in the west through to Windy Hill in the east, taking in the valley of the River Beal.[43][107] The Beal, a tributary of the River Roch, runs centrally through Milnrow from the south through Newhey.[107] The smaller Butterworth Hall Brook, which flows in to the Beal, runs east-to-west,[108] while Stanney Brook rises at High Crompton and runs along the southern edge of Milnrow and in to the Roch at Newbold in Rochdale.[39]

The 2001 Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary recounts Milnrow as both a town and a southeasterly suburb of Rochdale.[2] The Office for National Statistics designates Milnrow as part of the Greater Manchester Built-up Area, the United Kingdom's second largest conurbation.[109] Milnrow is situated in "the transitional zone" between the moorland of the South Pennines and the more densely populated areas of Rochdale and Manchester.[108] Most development has been built concentrically outwards from two centres by the River Beal in Milnrow and Newhey, but land use transitions as the height of the ground rises towards the Pennines – from commercial and industrial, to housing and suburban development, to enclosed farms and pastures, and finally unenclosed moorland at the highest points.[43][73][110] Ancient woodland is sparse; 1 acre (0.0016 sq mi) of woodland and plantation was recorded across Milnrow in 1911.[49] Housing includes 18th-century cottages and farmhouses, late-19th century terraced houses, inter-war social housing, and modern detached and semi-detached private family homes.[65] Farmland typically consists of undulating pastures used for stock rearing and rough grazing,[108][110] interspersed by isolated farmhouses and the Kitcliffe, Ogden and Tunshill hamlets.[65] Moorland forms the highest and most easterly part of Milnrow—the highest point is Bleakedgate Moor at 1,310 feet (399 m),[43] which forms a boundary with the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham by Denshaw. Windy Hill is another high-point amongst these moors.[43]

Milnrow's soil is typically light gravel and clay, with subsoil of rough gravel,[111] and the underlying geology is mostly lower coal measures from the Carboniferous period, punctuated with a band of sandstone.[112] Milnrow experiences a temperate maritime climate, like much of the British Isles, with relatively cool summers and mild winters. There is regular but generally light precipitation throughout the year.

In 1855, the poet Edwin Waugh said of Milnrow:

Milnrow lies on the ground not unlike a tall tree laid lengthwise, in a valley, by a riverside. At the bridge, its roots spread themselves in clots and fibrous shoots, in all directions; while the almost branchless trunk runs up, with a little bend, above half a mile towards Oldham, where it again spreads itself out in an umbrageous way.[6]

— Edwin Waugh, Sketches of Lancashire life and localities (1855)

The urban part of Milnrow broadly consists of development which has absorbed former hamlets including Butterworth Hall, Firgrove, Gallows, and Moorhouse. These now form neighbourhoods of Milnrow, but others form distinct settlements. For instance, Newhey, at the south of Milnrow, emerged as a village in its own right, with its own distinct amenities such as shops, parish church and Metrolink station.[39][12] Kitcliffe, Ogden and Tunshill, to the east of central Milnrow, are hamlets that occupy the upper, mid and lower Piethorne Valley respectively.[110][65] The Gallows area is signified by The Gallows public house—it is a former hamlet which now forms a neighbourhood. This area occupies an ancient execution site,[24][14][113] established by the Knights Hospitaller in 1253.[32] All continue to form a composite Milnrow area within the borough of Rochdale.[24]

Demography

.jpg.webp)

In 1855, the Rochdale-born poet Edwin Waugh described Milnrow's inhabitants as "a hardy moor-end race, half farmers, half woollen weavers".[39] Milnrow has been described as "the centre of the south Lancashire dialect",[5] while the accent of the town's inhabitants has been described variously as "strong", "common", "broad" or "northern"; a local pronunciation of Milnrow is "Milnra".[114] One of the most common surnames is Butterworth, which is native to the Milnrow area.[39] In 2016, a study in to life expectancy in Greater Manchester showed Milnrow to have one of the highest rates of longevity – second only to Whitefield – with the average woman living 82 years, and the average man for 75.[115] Robert Brearley was an early centenarian from Milnrow, who lived past his 103rd birthday between the years 1787 and 1889.[116]

According to the Office for National Statistics, at the time of the United Kingdom Census 2011, Milnrow (urban-core and sub-area) had a total resident population of 13,061.[117] This was up from the following figures recorded in 2001: 11,561 for the electoral ward of Milnrow (which has different boundaries),[118] 12,541 at the 2001 census,[119] and 12,800 from the Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary.[2]

Data from 2001 shows that of the residents in the electoral ward of Milnrow, which includes Newhey and the Piethorne Valley, 40.8% were married, 10.3% were cohabiting couples, and 9.5% were lone parent families. Twenty-seven per cent of households were made up of individuals, and 13% had someone living alone at pensionable age.[120] The economic activity of residents aged 16–74 was 45% in full-time employment, 12% in part-time employment, 7.7% self-employed, 2.6% unemployed, 2.1% students with jobs, 3.1% students without jobs, 13% retired, 4.6% looking after home or family, 7.4% permanently sick or disabled, and 2.3% economically inactive for other reasons. This was roughly in line with the national figures.[121] In 2019, Milnrow East & Newhey was estimated as having one of the highest prevalence of depression in England.[122]

The place of birth of the town's residents recorded in the 2001 census was 97% United Kingdom (including 95.04% from England), 0.6% Republic of Ireland, 0.5% from other European Union countries, and 2.6% from elsewhere in the world.[123] The ethnicity of the community was classified as 98% white, 0.7% mixed race, 0.8% Asian, 0.2% black and 0.3% Chinese or other.[124] In 2008, researchers with the University of Manchester noted Milnrow was a predominantly "White area", contrasted with areas within both the metropolitan boroughs of Rochdale and Oldham where large South Asian and British Asian communities were recorded.[125]

| Year | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1939 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 2001 | 2011 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 8,241 | 8,584 | 8,390 | 8,623 | 8,265 | 8,587 | 8,129 | 10,345 | 12,541 | 13,061 | |||

| Source:A Vision of Britain through Time | |||||||||||||

Declared religion from 2001 was recorded as 80% Christian, 0.8% Muslim, 0.1% Hindu, 0.1% Buddhist, and 0.1% Jewish. Some 12.2% were recorded as having no religion, 0.2% had an alternative religion, and 6.1% did not state their religion.[126] Historically, in addition to the established church, branches of Nonconformist Protestantism – particularly 18th-century Wesleyanism – were forms of Christian theology practised in Milnrow.[127] In 1717, Francis Gastrell, the then Bishop of Chester, noted there were "a few [...] avowed Presbyterians" in Milnrow.[49] In 1773, Baptists established a chapel at Ogden;[39] the building closed in 1964 with the congregation moving to a new building in Newhey in 1972, but retaining the name Ogden Baptist Church.[128] The Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion established a school in Milnrow in 1840, and St Stephen's Church building in 1861, attracting clergy and worshippers with leanings to Methodism and Calvinism; the congregation severed ties with the Connexion in 1865, and chose to join the Congregational Union.[34]

Economy

Prior to deindustrialisation in the late-20th century, Milnrow's economy was linked closely with a spinning and weaving tradition which had origins with domestic workshops but evolved in parallel with developments in textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution. Industries ancillary to textile production were present in the 19th century, such as coal mining at Tunshill,[42] metalworking at Butterworth Hall,[129] and brickmaking at Newhey.[130] Newhey Brick & Terracotta Works opened in 1899,[130] while Butterworth Hall Colliery was the largest colliery in the Rochdale region, employing around 300 men in 1912.[75] It was sunk as a commercial venture in 1861, opened fully in 1865, and was acquired by the Platt Brothers in 1881, continuing in their ownership until closure in 1928.[67] Modern sectors in the area include engineering, packaging materials, the dyeing and finishing of textiles and carpets, and ink production.[131] Milnrow constitutes a district centre, and Dale Street, its main thoroughfare, forms a linear commercial area with convenience stores, restaurants and food outlets, and a mix of independent shops and services including hairdressing and legal services.[132][133][134] An Aldi supermarket was opened in 2016 by Bianca Walkden,[135] while The Milnrow Balti won the 2019 Curry Life award for Best Restaurant in Greater Manchester.[136] There are smaller, lower-order shops in Newhey.[66][132] Animal husbandry, grazing and other farming practices occur on pastures at Milnrow's rural fringe.[108]

The biggest employers in Milnrow are Holroyd Machine Tools, part of Precision Technologies Group who have been based in the town since they moved from Manchester in 1896.[137] In the early-20th century they operated a foundry in Whitehall Street and employed engineers and apprentices.[137] In 2006 Holroyd had a workforce of 160, and its parent company Renold PLC employed a further 200 people at a base in there.[138][139][140] Since 2010 Holroyd has been owned by the Chongqing-based CQME group.[141] Holroyd at Milnrow was visited by Nick Clegg in his capacity as Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in April 2011.[142] Global industrial and consumer packaging company Sonoco operate a warehouse in the town.[143] Over half-a-million units of local delicacy Rag Pudding are mass-produced by Jackson's Farm Fayre in their Milnrow factory.[144] In Newhey, Sun Chemical produce printer inks and supplies,[145] and Newhey Carpets design and produce carpets from a former Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway warehouse.[39][146] At Ogden, textiles are dyed and finished by PW Greenhalgh.[147]

Kingsway Business Park will be a 420-acre (1.7 km2) "business-focused, mixed use development" occupying land between Milnrow and Rochdale, adjacent to junction 21 of the M62 motorway; it is expected to employ 7,250 people directly and 1,750 people indirectly by around 2020.[148] Tenants on the park in 2011 included JD Sports and Wincanton plc.[149] Kingsway Business Park tram stop was built as part of Phase 3a of Metrolink's expansion, and serves Kingsway Business Park.[150]

Landmarks

Milnrow's historic architecture is chiefly marked by its 18th-century sandstone weavers' cottages,[152] three-storey "fine stone domestic workshops" with mullioned windows.[42][51][153][52] Also known as loomshops or loomhouses, it was estimated in 1982 that Milnrow likely had the greatest concentration of surviving weavers cottages in North West England.[154] A conservation area was created in Ogden in 1974 to protect a range of stables, farm houses and former schoolhouse.[155] Two conservation areas were created in 2006 at Butterworth Hall, covering domestic and municipal buildings respectively in central Milnrow.[156][157] Former family seats and manor houses – of mostly medieval origin – in the area have included Belfield Hall, Butterworth Hall, Clegg Hall, and Schofield Hall. Belfield Hall, at Milnrow's western boundary with Rochdale, was occupied by a variety of dignitaries, including two High Sheriffs of Lancashire — Alexander Butterworth and Richard Townley.[111][158] Clegg Hall, at Milnrow's northern boundary with Littleborough, is an early-17th century country house with Grade II* listed building status.[34]

The Grade II listed Church of St James, Milnrow's Anglican parish church, was built in 1869 and is dedicated to James the Apostle.[159] It is part of the Church of England and lies within the Anglican Diocese of Manchester.[160] The origins of the church can be traced to a chantry or oratory built by the Byrons in the year 1400. When that ruling family moved from Milnrow to another of their homes following the Wars of the Roses, the local population was left without a place of worship and a chapel was constructed by the River Beal in 1496 to serve this community.[37] This structure existed until the 1790s, when a "poorly designed" chapel was erected and consecrated; however, due to structural weaknesses, that church was demolished in 1814.[37] Following an interim period when a "plain building" was used for worship, the present church building was built and consecrated by James Fraser, the Bishop of Manchester, on 21 August 1869.[151] Inside, the capitals have foliage decoration sculpted by the "foremost Victorian stonemason" Thomas Earp.[161][159][162]

Described as "by far the most distinctive and splendid building in the district",[151] the neo-Gothic Newhey, St Thomas parish church was built in 1876 and served a new Anglican parish of Newhey created in the same year.[163] Dedicated to Thomas the Apostle, it is part of the Church of England, and its patron is the Bishop of Manchester.[164] The church was extensively damaged in an arson attack on 21 December 2007,[165] but later restored in full.[39]

Milnrow War Memorial is located in Milnrow Memorial Park at Newhey, and is a Grade II listed structure.[166] The war memorial was originally sited in central Milnrow, set back from the road near Milnrow Bridge, and was unveiled on 3 August 1924 by Major General Arthur Solly-Flood, a former commander of 42nd (East Lancashire) Division. The memorial is constructed of sandstone surmounted by a bronze statue of a First World War infantryman with rifle and fixed bayonet symbolic of the young manhood of the district in the early days of the First World War. In selecting the design the Milnrow War Memorial Committee was influenced by the statue unveiled at Waterhead in Oldham; the work of George Thomas. Thomas sculpted Milnrow's memorial in 1923. The plinth holds bronze and slate panels recording the names of those who died in the two World Wars.[167][168]

In Newhey is the Ellenroad Steam Museum, the retained engine house, boiler house, chimney and steam engine of Ellenroad Mill, a former 1892-built cotton mill designed by Sir Philip Stott, 1st Baronet. Now operated as an industrial heritage centre, the mill itself is no longer standing, but the steam engine (the world's largest working steam mill engine)[169] is maintained and steamed once a month by the Ellenroad Trust.[170] The museum has the only fully working cotton mill engine with its original steam-raising plant in the world.[171] Ellenroad Mill produced fine cotton yarn using mule spinning.[169] A 1907-built, working tandem compound condensing engine, made by J. & W. McNaught for Firgrove Mill in Milnrow, is displayed in the Science and Industry Museum in central Manchester.[172][173]

Transport

.jpg.webp)

Public transport in Milnrow is co-ordinated by Transport for Greater Manchester, and services include bus and light rail transport. Major A roads link Milnrow with other settlements – the A640 road, which forms a route from Newhey and over the Pennines into Huddersfield and West Yorkshire, was established by a turnpike trust in 1805.[55] Another A road is the Elizabethan Way bypass, which was opened around 1971 to coincide with the opening of Junction 21 of the trans-Pennine M62 motorway.[91] Construction of the Milnrow part of the M62 began in April 1967,[174] a process which spread mud and dirt throughout the town,[86] and the relocation of inhabitants due to the demolition of homes.[175] The official opening of the motorway on 13 October 1971 was by Queen Elizabeth II, who was welcomed by Ralph Assheton, 1st Baron Clitheroe in his role as Lord Lieutenant of Lancashire, as well as the Chairman of Milnrow Urban District Council and his wife.[86] Once opened, the Queen cast aside protocol for an informal meeting with the people of Milnrow.[86] A Highways England motorway compound is located in Milnrow.[91][176]

Milnrow had a first-generation electric passenger tramway in operation between 1909 and 1932. It was part of the broader Rochdale Corporation Tramways network, with a single route which started initially from Firgrove in the west, and joining Newhey in the south when the line was completed in 1912.[39][74] The tramway had a reputation for poor maintenance, and suffered from increasingly frequent derailments towards its closure.[39] The modern extant Milnrow tram stop is part of the Metrolink light-rail system, on the Oldham and Rochdale Line, with services operating towards Rochdale or Manchester city centre every 12 minutes. It was previously a heavy railway station on the Oldham Loop Line which connected Manchester, Oldham and Rochdale.[43] The station was constructed in 1862 by navvies drafted by contractors under the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. On 12 August 1863 the line was opened to commercial traffic, and 2 November 1863 to passenger trains.[177] Milnrow railway station was originally staffed, and the line through it was dual-track; however this section was reduced to single-track in 1980.[177] Milnrow railway station closed on 3 October 2009 to be converted for use with an expanded Metrolink network.[178][179] The station reopened on 28 February 2013 as Milnrow tram stop; also opening at this time in the Milnrow area was Kingsway Business Park tram stop and Newhey tram stop.[90]

The Rochdale Canal—one of the major navigable broad canals of Great Britain—passes along Milnrow's north-western boundary which divides it from the village of Wardle and districts of Belfield and Castleton in Rochdale.[180] The Rochdale Canal was historically used as a highway of commerce for the haulage of cotton, wool, and coal to and from the area.

Bus service 182 operates to Rochdale, Newhey, Oldham, and Manchester, while services R4 and R5 serve Rochdale and the estates of Milnrow and Newhey, operated by First Greater Manchester and Burnley Bus Company.[181]

Education

The Free School of Milnrow was founded in 1726 and was demolished in the early-1950s.[182] From 1739 until his death in 1786 the schoolmaster was the caricaturist John Collier.[111] In the mid-19th century it was part of the British and Foreign School Society.[183] Newhey Council School was constructed in 1911,[184] and now forms Newhey Community Primary School. By 1918 there were five public elementary schools; the Milnrow and Newhey council schools; St James's of Milnrow and St Thomas' of Newhey Anglican schools; and Ogden church school.[39] Milnrow St James School evolved into the modern primary school, Milnrow Parish Church of England Primary.[185] It is a denominational school with the Church of England, linked with Milnrow's Anglican parish church, St James's. There are further primary schools named Crossgates Primary and Moorhouse Primary, both of which are non-denominational.[186][187] Crossgates Primary School won the British Council's International School Award in 2010 for its teaching of culture and global citizenship.[188] Hollingworth Academy is a secondary school in Milnrow with Academy school status.[189] It occupies the site of the former Roch Valley County Secondary School, which opened in 1968 and closed in 1990.[190] It is a co-educational school of non-denominational religion.[191]

Sports and culture

Milnrow has a "distinct and separate character".[4] It is one of the towns of northern England that observed the custom of Rushbearing, an annual Anglican religious festival where rushes are brought by rushcart to by strewn in the parish church to refresh the flooring. Milnrow's Rushbearing occurred on the Sunday prior to St James's Day,[192] and in 1717, Francis Gastrell, the Bishop of Chester, wrote that Milnrow's festival was a particularly "disorderly custom".[192] Parishioners would travel as far as Marsden to gather rushes.[193] Established in 1968,[194] Milnrow and Newhey Carnival is an annual summer community parade with floats, morris dancers and brass bands.[194][195] The Milnrow Band is a British brass band ranked as a "top class group of amateur musicians".[196] It formed from a succession of mergers and amalgamations of Milnrow- and Rochdale-based brass bands,[197] the earliest of which was St Stephen's Band founded in Milnrow in 1869.[196] In 2006 it was promoted to the top-rank Championship section of Great Britain, and in 2017 were the All England Masters International Champions.[196] In his 2015 memoir, the Manchester-born comedy-singer Mike Harding recalled "a place called Milnrow, on the extreme edge of the then known world, [...where...] everything stopped for pie and peas".[198]

Milnrow Cricket Club is based at Ladyhouse in Milnrow, and has played in the Central Lancashire Cricket League since its foundation in 1892. The club formed in 1857 from a group of local businessmen who felt the district deserved its own distinct team. Originally, members of the club were recruited and teams were selected to play other clubs in the surrounding townships.[199] Later players have included Cec Abrahams, who joined the club in 1961, having previously played for the South Africa national cricket team.[200] Used for casual, amateur and organised leagues and tournaments, The Soccer Village in Milnrow consists of four indoor pitches in an arena with grandstand spectator seating for 300.[201] There has been a golf course at Tunshill since 1901.[72] It is affiliated with the English Golf Union. Land in Firgrove was gifted to Milnrow Council in November 1934 for use as a sports pitch, establishing the Firgrove Playing Fields.[81] They are used for rugby league, rounders and association football,[202] and are the home of Rochdale Cobras ARLFC,[203] a club which won the British Amateur Rugby League Association "Club of the Year" award in 2011.[203] New Milnrow and Newhey Rugby League Club is a further local rugby league club.[204]

Milnrow Memorial Park includes a multi-purpose asphalt football/basketball court, a bowling green, children's play park and a concrete skatepark.

Public utilities

.jpg.webp)

Milnrow was identified as a suitable source of drinking water on an industrial scale in the Victorian era, when the Oldham Corporation obtained rights to dam the Piethorne Brook.[205] Excavations began in 1858, and concluded in 1863 with the opening of the Piethorne Reservoir.[205] By 1869, the Oldham Corporation acknowledged there was "an absolute necessity for an extra water supply",[205] and further reservoirs were created using English compulsory purchase powers granted to the Corporation by virtue of the Oldham Improvement Act 1880.[71] In 1918, the Oldham Corporation was still one of the largest landowners in Milnrow.[39] United Utilities now operate the reservoir.[206]

In 1950, the General Post Office was contracted to construct a new-generation British Telecom microwave network, transmitting BBC television across Great Britain. By 1951, a transmitter station had been built on Milnrow's outlying Windy Hill, carrying signals broadcast from Manchester to Tinshill and then on to Kirk o'Shotts transmitting station.[207] Initially overlooked for a site in Saddleworth,[208] in the late-1950s, Windy Hill transmitter station became part of Britain's "backbone network", a series of telecommunications towers in the United Kingdom designed to maintain communications in the event of a Cold War-era nuclear attack.[209] The station forms a landmark on the landscape, adjacent to the Pennine Way long-distance footpath and M62 motorway.[210]

Waste management is co-ordinated by the local authority via the Greater Manchester Waste Disposal Authority.[211] Milnrow's distribution network operator for electricity is United Utilities;[206] there are no power stations in the area, but a Wind farm exists on Scout Moor which consists of 26 turbines on the high moors between Rawtenstall and Rochdale, generating 65MW of electricity.[212]

Home Office policing in Milnrow is provided by the Greater Manchester Police. The force's "(P) Division" have their headquarters for policing the Metropolitan Borough of Rochdale in Rochdale and the nearest police station is at Littleborough to the north.[213] Statutory emergency fire and rescue service is provided by the Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service, which has one station in Rochdale on Halifax Road.[214]

There are no hospitals in Milnrow—the nearest are in Oldham and Rochdale; the Royal Oldham Hospital and Rochdale Infirmary are managed by the Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust, a part of the Northern Care Alliance NHS Group. The North West Ambulance Service provides emergency patient transport. Primary care and general practice occurs at Stonefield Street Surgery.[215] The Milnrow Village Practice was surveyed as the 2nd best general practice in Greater Manchester for patient experience in both 2018 and 2019.[216][217]

Notable people

John Collier (who wrote under the pseudonym of Tim Bobbin) was an acclaimed 18th-century caricaturist and satirical poet who was raised and spent all his adult life in Milnrow.[218] Born in Urmston in 1708, Collier was schoolmaster for Milnrow.[218] Inspired by William Hogarth, Collier was admired by Sir Walter Scott,[39] and called a "man of original genius" by Edward Baines.[30] His work savagely lampooned the behaviour of upper and lower classes alike, and was written in a strong Lancashire dialect.[218][219] Many of his works and personal possessions are preserved in Milnrow Library,[220] and he is commemorated in the name of a "prominent pub" in central Milnrow.[43][218] Collier's great-grandson—also called John and a native of Milnrow—was one of the founding members of the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers.[4]

Francis Robert Raines (1805–1878) was the Anglican vicar of Milnrow, and an antiquary who contributed to the Chetham Society publications.[221] He was ordained in 1828 and, after short appointments at Saddleworth and Rochdale, he was vicar at Milnrow for the rest of his life.[221] John Milne was a professor, geologist and mining engineer who invented a pioneering seismograph (known as the Milne-Shaw seismograph) to detect and measure earthquakes. Although born in Liverpool in 1850 owing to a brief visit there by his parents, Milne was raised in Rochdale and at Tunshill in Milnrow.[222][223]

Other notable people of Milnrow include Cec Abrahams, a South African-born international cricketer, who settled in the town during the 1960s and played for the local cricket club,[200] Chris Dunphy, the Milnrow-born chairman of Rochdale A.F.C.,[224] and Lizzy Bardsley, who, in 2003, gained fame from appearing on Channel 4's Wife Swap.[225][226] Stuart Bithell, who won a Silver Medal in the Men's 470 class at the 2012 Summer Olympics, was raised in Newhey,[227] and Martin Stapleton, a mixed martial artist who was the 2015 BAMMA World Lightweight Champion resided in Milnrow as of 2019.[228][229]

Footnote

- Hollingworth was anciently part of the Butterworth township. It was to the north of Milnrow; but absorbed into the Littleborough Urban District in the late-19th century.

References

Notes

- "Milnrow". Brewer's Britain and Ireland. credoreference.com. 2005. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

A former cotton town in Greater Manchester

(subscription required) - "Miln•row". Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary. credoreference.com. 2007. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

Town, Greater Manchester, NW England, SE suburb of Rochdale; pop. (2001e) 12,800.

(subscription required) - "Greater Manchester Gazetteer". Greater Manchester County Record Office. Places names – M to N. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- Rochdale Pioneers Museum. "Milnrow, Newhey and Ogden Co-operative Heritage Trail" (PDF). rochdalepioneersmuseum.coop. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- Joyce (1993), p. 198.

- Waugh 1855, p. 61

- University of Manchester Archaeological Unit 1996, p. 4

- Hartwell, Hyde & Pevsner (2004), p. 12

- Historic England. "Monument No. 45988". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 25 April 2008.

- B Pearson; J Price; V Tanner; J Walker. "The Rochdale Borough Survey" (PDF). Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit.

- Bateson 1949, p. 3

- Healey 2008, p. 11

- Poole, S. (1986). "A Late Mesolithic and Early Bronze Age Site at Piethorn Brook, Milnrow". Greater Manchester Archaeological Journal. 2: 11–30.

- Hignett (1991), p. 3.

- University of Manchester Archaeological Unit 1996, p. 14

- Historic England. "Monument No. 46071". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- Mattley 1899, p. 8

- Healey 2008, p. 2

- Kenyon 1991, p. 137

- March, Henry Colley (1880). East Lancashire Nomenclature and Rochdale Names. London: Simpkin & Co. ASIN B0014M51VQ.

- Mills 1976, p. 69

- Oakden, Vanessa; Okasha, Elisabeth (2012). "A Pre-Conquest Latin Inscription from North-West England". Medieval Archaeology. 56 (1): 260–300. doi:10.1179/0076609712Z.0000000009. S2CID 218680879.

- Mills 2011, p. 328

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council (N.D.), p. 32.

- Hignett (1991), p. 2.

- Ekwall (1972), p. 56.

- Manchester City Council. "Rochdale Towns". spinningtheweb.org.uk. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- "Descriptive Gazetteer entry for Butterworth". visionofbritain.org.uk. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- University of Manchester Archaeological Unit 1996, p. 75

- Baines 1825, pp. 532–533

- Lofthouse 1972, p. 28

- Mattley 1899, p. 1

- Baines 1825, pp. 688–689.

- "'Iron church', textile giants and industrial chain gangs". The Rochdale Observer. Rochdale. 25 March 2017.

- Mattley 1899, p. 3

- Rochdale Boroughwide Cultural Trust. "Events in Milnrow 1400–1929!". link4link.org. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- Hignett (1991), p. 32.

- Kümin 2016

- Godfrey 2018

- Fishwick 1889, p. 122.

- University of Manchester Archaeological Unit 1996, p. 80

- McNeil, R. & Nevell, M. (2000), p. 35.

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council 1985, p. 33

- Fishwick 1889, p. 54.

- Collins 1950, p. 30

- Cresswell 1991, p. 168

- Lewis 1848, p. 318

- Hignett (1991), p. 10.

- "The parish of Rochdale". A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 5. 5.0. british-history.ac.uk. 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- University of Manchester Archaeological Unit 1996, p. 82

- Frangopulo (1977), p. 29.

- "Housing continued". BBC Domesday Reloaded. bbc.co.uk. 1986. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Navickas 2009, pp. 21–22

- Healey 2008, p. 10

- "No. 15881". The London Gazette. 14 January 1806. p. 61.

- Gregory, Richard (2019). Yeoman Farmers and Handloom Weavers: the archaeology of the Kingsway Business Park. Lancaster: Oxford Archaeology Ltd. pp. 21–31. ISBN 978-1-907686-28-3.

- Gregory, Richard (2021). Farmers and Weavers: archaeological investigations at Kingsway Business Park and Cutacre Country Park, Greater Manchester. Lancaster: Oxford Archaeology Ltd. pp. 137–163. ISBN 978-1-907686-36-8.

- Trower 2011, p. 61

- Butterworth (1828), p. 113.

- Hignett (1991), p. 11.

- Robertson 1877, p. 132

- Tedd 2002, p. 236

- Sellers (1991), p. 47.

- The British Trade Journal and Export World 1886, p. 347.

- "Housing". BBC Domesday Reloaded. bbc.co.uk. 1986. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- "Changing Times". BBC Domesday Reloaded. bbc.co.uk. 1986. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- National Mine Research Society. "Butterworth Hall Colliery (1865–1928)". nmrs.org.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- The Journal of gas lighting, water supply and sanitary improvement 1869, pp. 297–300.

- Procter, S. & Toms, S. (2000). "Industrial Relations and Technical Change: Profits, Wages and Costs in the Lancashire Cotton Industry, 1880–1914" (PDF). eprints.whiterose.ac.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

- "Leaders of industry who used home life as symbol of power". Manchester Evening News. 13 August 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- "No. 25533". The London Gazette. 24 November 1885. pp. 5486–5489.

- "Welcome to the Tunshill Golf Club Website". tunshillgolfclub.co.uk. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- Hignett (1991), p. 7.

- "No. 28312". The London Gazette. 26 November 1909. p. 9013.

- Godman 1996, p. 59.

- Royal Society of Medicine 1915, p. 100

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Blazing revival led to disaster". Manchester Evening News. 21 March 2006. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Tank floral display installed in Milnrow". Rochdale Online. 17 July 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "Milnrow Tank To GO: War Relic to be scrapped". Rochdale Observer. Rochdale. June 1934.

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council (8 December 2016). "Milnrow, Newhey and Firgrove Area Forum Thursday, 8th December, 2016 7.00 pm". Agenda and minutes. democracy.rochdale.gov.uk. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "Council Housing". parliament.uk. 18 March 1996. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- "Milnrow Memorial Park: History". Rochdale Online. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- Rochdale Council. "Milnrow Memorial Park, Green Flag Award". rochdale.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- "This is Milnrow: Industry". milnrow-village.freeserve.co.uk. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- Hignett (1991), p. 35.

- "A Brief History of the Rochdale Canal". Manchester Evening News. 24 April 2005. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- "Firgrove Bridge, Rochdale". penninewaterways.co.uk. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- "Green light for 66 homes on former mill site". Manchester Evening News. 25 April 2005. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "Rochdale extension to Metrolink tram network opens". bbc.co.uk. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- "Transport". BBC Domesday Reloaded. bbc.co.uk. 1986. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "The astonishing community volunteers in Milnrow who stayed up all night to help drivers stranded on the M62". Manchester Evening News. 2 March 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- "UK snow: M62 drivers stranded 'indefinitely'". BBC News. bbc.co.uk. 2 March 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council (N.D.), p. 19.

- University of Manchester Archaeological Unit 1996, p. 78

- Baines 1825, p. 689.

- Mattley 1899, p. 48

- Mattley 1899, p. 50

- "No. 23583". The London Gazette. 4 February 1870. pp. 665–666.

- Mattley 1899, p. 52

- Garrard 1983, p. 93

- Clark 1973, p. 106.

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council. "Local MPs and MEPs – information and advice". rochdale.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 1 June 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- Wainright, Martin (29 April 2010). "Labour loyalty starts to wear thin in Oldham". The Guardian.

- Waller & Criddle 2002, p. 619

- "Milnrow, United Kingdom". Global Gazetteer, Version 2.1. Falling Rain Genomics, Inc. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- Hignett (1991), p. 6.

- Bullock & Blythe 2009, p. 5

- Office for National Statistics (2001). "Census 2001:Key Statistics for urban areas in the North; Map 3" (PDF). statistics.gov.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2007. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council 2006, p. Supplementary Map

- Brownbill, J; William Farrer (1911). A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 5. Victoria County History. pp. 213–222. ISBN 978-0-7129-1055-2.

- Bullock & Blythe 2009, p. 6

- Lewis (1848), pp. 729–733.

- Fitzgerald, Todd (5 August 2015). "Scally or posh? Greater Manchester accent map shows what people think about the way YOU talk". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "Greater Manchester Metrolink tram map reveals life expectancy levels". BBC News. bbc.co.uk. 7 October 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- Mattley 1899, p. 98

- "Town population 2011". Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- United Kingdom Census 2001 (2001). "Milnrow (Ward)". neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- Office for National Statistics. "Greater Manchester Urban Area". statistics.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

- United Kingdom Census 2001 (2001). "Milnrow (Ward): Household Composition". neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- United Kingdom Census 2001 (2001). "Milnrow (Ward): Economic Activity". neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- Pidd, Helen (6 May 2019). "Most depressed English communities 'in north and Midlands'". theguardian.

- United Kingdom Census 2001 (2001). "Milnrow (Ward): Country of Birth". neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- United Kingdom Census 2001 (2001). "Milnrow (Ward): Ethnic Group". neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- Simpson, Ahmed & Phillips 2008, p. 11

- United Kingdom Census 2001 (2001). "Milnrow (Ward): Lead Key Figures". neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- Hignett (1991), p. 34.

- "The Rochdale Baptists 1773 – 1973: A Short History" (PDF). baptisthistory.org.uk. 1973. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Godman 1996, p. 63

- "The 1890s". Manchester Evening News. 13 August 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- Rochdale Boroughwide Cultural Trust. "Milnrow & Newhey". link4life.org. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- "Shopping and Commerce". BBC Domesday Reloaded. bbc.co.uk. 1986. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council 2006, p. 75

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council 2006, p. 80

- "New Aldi store opens in Milnrow". Rochdale Online. 17 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "Milnrow restaurant and takeaway named Curry Life Awards Best Restaurant". Rochdale Online. 9 November 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- Godman 1996, p. 62.

- Foster, Stephen (4 July 2006). "Buyers are all set to move in on company". rochdaleobserver.co.uk. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- Anon (20 March 2006). "In gear for good news story still on the run". rochdaleobserver.co.uk. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- "Renold Gears, Rochdale". renold.com. 2004. Retrieved 29 April 2003.

- "Holroyd gets Chinese owner in £20m deal". drivesncontrols.com. 18 March 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- "Nick Clegg announces Regional Growth Fund winners in Rochdale". Rochdale Online. 13 April 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- Sonoco Products. "Sonoco Locations". sonoco.com. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- Foster, Stephen (28 April 2007). "Rag trades 'puds' tapas to shame". Manchester Evening News. menmedia.co.uk. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- "Printers Services & Supplies in Rochdale". Rochdale Online. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- "Newhey Carpets". newheycarpets.co.uk. About; and Contact Us. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- "Contact Us". pwgreenhalgh.com. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- "Key Facts". Kingsway. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- "Asda to create 800 new jobs with new distribution centre on Kingsway Business Park". Manchester Evening News. menmedia.co.uk. 9 August 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- Light Rail Transit Association (24 September 2008). "Manchester to Oldham and Rochdale". lrta.org. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- Hignett, (1991), p. 33.

- Hartwell, Hyde & Pevsner (2004), p. 46

- Frangopulo (1977), p. 149.

- Trinder 1982, p. 192

- Rochdale Council (24 July 2014). "Ogden Conservation Area" (PDF). rochdale.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Rochdale Council (24 July 2014). "Butterworth Hall Conservation Area" (PDF). rochdale.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Rochdale Council (24 July 2014). "Butterworth Hall (Municipal Buildings) Conservation Area" (PDF). rochdale.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Rochdale Boroughwide Cultural Trust. "Events in Milnrow 1400–1929!". link4link.org. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- Historic England (2001). "Church of Saint James, Milnrow (1260729)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- "Milnrow, Saint James". manchester.anglican.org. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- Hartwell, Hyde & Pevsner (2004), p. 521

- "Milnrow Parish Church: St James the Apostle – Heritage Open Days". Rochdale Online. 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- "A vision of Newhey EP". visionofbritain.org.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- "Townships – Butterworth". british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

- McKeegan, A. & Beckett, J. (24 December 2007). "Church hit by fire". rochdaleobserver.co.uk. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- Historic England (2001). "Milnrow War Memorial (1162572)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council. "Memorial – maintenance". rochdale.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 17 October 2008. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

- Public Monuments and Sculpture Association (16 June 2003). "Milnrow War Memorial". Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- "Ellenroad Steam Museum". industrialpowerhouse.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 1 May 2008.

- McNeil, R. & Nevell, M. (2000), p. 39.

- "Welcome to Ellenroad!". ellenroad.org.uk. Retrieved 1 May 2008.

- "Firgrove Mill Steam Engine". sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Barlow, Nigel (21 January 2020). "Manchester's Science and Industry Museum needs some help". aboutmanchester.co.uk. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- "Unlocking the door to heart of the nation". rochdaleobserver.co.uk. 17 June 2006. Archived from the original on 6 September 2008. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

- "No fairies at the bottom of this garden". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Kirby, Dean (18 April 2010). "On a highway patrol". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Hignett (1991), p. 26.

- Kirby, Dean (1 October 2009). "Signalman reaches end of line". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- "End of era as loop line is replaced". Manchester Evening News. 26 September 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- Rochdale (Map) (1908 ed.). Cartography by Ordnance Survey. Alan Godfrey Maps. 2002. § Lancashire Sheet 89.01. ISBN 1-84151-384-9.

- "Transport for Greater Manchester".

- Taylor 1956, p. 79

- Anon. 1847, p. 422

- Hignett (1991), p. 15.

- "Milnrow Parish CofE Primary, Rochdale". milnrowparishce.rochdale.sch.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

- "Newhey Community Primary School". newhey.rochdale.sch.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

- "Crossgates Primary School: Welcome to our school". crossgates.rochdale.sch.uk. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- "Award triumph for Milnrow school". Rochdale Online. 11 November 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Hollingworth Business and Enterprise College". hollingworthbec.co.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- Bullock & Blythe 2009, p. 3

- "Hollingworth High School, Rochdale". axcis.co.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- Burton 1891, p. 73

- Marsden History Group. "Public houses". marsdenhistory.co.uk. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- "Milnrow and Newhey Carnival celebrating 50 years with Golden Jubilee and the 60s theme". Rochdale Online. 11 May 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "Milnrow Carnival". BBC Domesday Reloaded. bbc.co.uk. 1986. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "About Milnrow Band". milnrowband.co.uk. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Holman 2018

- Harding 2015

- "150 Years of History". milnrowcc.com. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- "The father of a cricketing dynasty". Manchester Evening News. 13 August 2007. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- "Welcome to The Soccer Village Website". soccervillage.net. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council (September 2016). "Rochdale Borough Council Playing Pitch Strategy 2016–2026" (PDF). consultations.rochdale.gov.uk. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "Rochdale Cobras ARLFC". Rochdale Online. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "Milnrow & Newhey ARLFC Reunion". Rochdale Online. 12 June 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Institution of Civil Engineers 1872, p. 208

- United Utilities (6 April 2007). "Rochdale". unitedutilities.com. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- "Windy Hill". dgsys.co.uk. 15 July 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- "Backbone radio link and radio standby to line links for safeguarding vital communications". British GPO paper. The National Archives (United Kingdom) CAB 134/1207. July 1956. Archived from the original on 4 October 2009.

- Craine & Ryan 2011, pp. 139–140

- Bowden 2015

- Greater Manchester Waste Disposal Authority (2008). "Greater Manchester Waste Disposal Authority (GMWDA)". gmwda.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- "Scout Moor Wind Farm". scoutmoorwindfarm.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 February 2008. Retrieved 2 March 2008.

- Greater Manchester Police (26 January 2006). "Pennine policing area". gmp.police.uk. Archived from the original on 7 November 2007. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service. "My area: Rochdale". manchesterfire.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2008. Retrieved 7 March 2008.

- "Stonefield Street Surgery". stonefieldstreetsurgery.co.uk. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Ottewell, David; Day, Rebecca (13 August 2018). "How do patients rate the GP surgery you go to?". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Ottewell, David; Yarwood, Sam (4 September 2019). "How good is your doctor's surgery? Check the rating of every practice in Greater Manchester with our widget". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- "John Collier – "Tim Bobbin"". BBC Domesday Reloaded. bbc.co.uk. 1986. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- Hignett (1991), p. 39.

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council (N.D.), p. 33.

- "Early Ministers of Milnrow". Lancashire OnLine Parish Clerk Project. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- McKeegan, Alice (27 October 2007). "Famous scientists on road to name wrangle". rochdaleobserver.co.uk. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

- Hignett (1991), p. 38.

- Ashdown, John (21 September 2008). "Homespun Rochdale offer stability away from the Billionaire Boys' Clubs". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- Hopton, Katie (14 October 2003). "Wife-swap Lizzy insists: 'I'm a star'". rochdaleobserver.co.uk. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

- "'Wife Swap' star's benefit charge". news.bbc.co.uk. 16 November 2004. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- "Let Olympics spur you on to sporting glory". Manchester Evening News. menmedia.co.uk. 18 August 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- "Martin Stapleton declares UFC ambitions after signing for Cage Warriors". rochdaleonline.co.uk. 12 January 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Companies House. "Martin STAPLETON". companieshouse.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

Bibliography

- The British Trade Journal and Export World. Vol. 24. 1886.

- Anon. (1869). The Journal of gas lighting, water supply and sanitary improvement. Vol. 18.

- Anon. (1847). The Parliamentary Gazetteer of England and Wales. Vol. 3. A. Fullarton and Company.

- Baines, Edward (1825). History, Directory, and Gazetteer, of the County Palatine of Lancaster: With a Variety of Commercial & Statistical Information. Vol. II. Lancashire (England): W. Wales & Company.

- Bateson, Hartley (1949). A Centenary History of Oldham. Oldham County Borough Council. ISBN 5-00-095162-X.

- Bowden, Andrew (2015). See You in Kirk Yetholm: Tales From The Pennine Way. Rambling Man.

- British Dam Society (2002). Tedd, P. (ed.). Reservoirs in a Changing World. Thomas Telford. ISBN 9780727731395.

- Bullock, Vicki; Blythe, Kathryn (May 2009). Hollingworth High School, Rochdale, Greater Manchester: Archaeological Desk-based Assessment (PDF). Lancaster, Lancashire: Oxford Archaeology North.

- Burton, Alfred (1891). Rush-Bearing. Brook & Chrystal. ISBN 9781291941807.

- Butterworth, James (1828). A History And Description of the Town And Parish of Rochdale in Lancashire. W D Varey.

- Clark, David M. (1973). Greater Manchester Votes: A Guide to the New Metropolitan Authorities. Redrose.

- Collins, Herbert C. (1950). The Roof of Lancashire. J. M. Dent and Sons.

- Craine, Simon; Ryan, Noel (2011). Protection from the Cold": Cold War Protection in Preparedness for Nuclear War. Wildtrack Publishing. ISBN 9781904098195.

- Cresswell, Mike (1991). Rambles Around Manchester: Walks Within 25 Miles of the City Centre. Cumbria: Sigma Leisure. ISBN 9781850582335.

- Ekwall, Eilert (1972) [1922]. The place-names of Lancashire. E.P. Publishing. ISBN 0-85409-823-2.

- Fishwick, Henry (1889). The History of the Parish of Rochdale in the County of Lancaster. James Clegg.

- Frangopulo, N. J. (1977). Tradition in Action: The Historical Evolution of the Greater Manchester County. Wakefield: EP Publishing. ISBN 0-7158-1203-3.

- Garrard, John (1983). Leadership and Power in Victorian Industrial Towns, 1830-80. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719008979.

- Godfrey, Alan (2018). Milnrow & Newhey 1907: Lancashire Sheet 89.06. Old Ordnance Survey Maps. Consett: Alan Godfrey Maps. ISBN 978-1-78721-133-9.

- Godman, Pam (1996). Rochdale: Pocket Images. NPI Media Group. ISBN 978-0-7524-0382-3.

- Harding, Mike (2015). The Adventures of the Crumpsall Kid: A Memoir. Michael O'Mara Books. ISBN 9781782434535.

- Hartwell, Clare; Hyde, Matthew; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2004). Lancashire: Manchester and the South-East. The Buildings of England. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10583-5.

- Healey, Chris (2008). Alison Plummer (ed.). Wickenhall to Newhey Pipeline, Piethorne, Greater Manchester (PDF). Lancaster: Oxford Archaeology North.

- Holman, Gavin (2018). Brass Bands of the British Isles 1800–2018: A Historical Directory.

- Hignett, Tim (1991). Milnrow & Newhey: A Lancashire Legacy. Littleborough: George Kelsall Publishing. ISBN 0-946571-19-8.

- Institution of Civil Engineers (1872). James Forest (ed.). Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. Vol. 33. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Joyce, Patrick (1993). Visions of the People: Industrial England and the Question of Class, c.1848–1914. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44797-3.

- Kenyon, D (1991). The Origins of Lancashire. Manchester.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kümin, Beat A. (2016). The Shaping of a Community: The Rise and Reformation of the English Parish c.1400–1560. St Andrews Studies in Reformation History. Routledge. ISBN 9781351881982.

- Lewis, Samuel (1848). A Topographical Dictionary of England. Institute of Historical Research. ISBN 978-0-8063-1508-9.

- Lofthouse, Jessica (1972). Lancashire's Old Families. Hale. ISBN 9780709133308.

- Mattley, Robert Dawson (1899). Annals of Rochdale: A Chronological View from the Earliest Times to the End of the Year 1898. Rochdale, England: James Clegg.

- Navickas, Katrina (2009). Loyalism and Radicalism in Lancashire, 1798–1815. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199559671.

- McNeil, R. & Nevell, M (2000). A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Greater Manchester. Association for Industrial Archaeology. ISBN 0-9528930-3-7.

- Mills, David (1976). The Place-Names of Lancashire. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mills, David (2011). A Dictionary of British Place-Names. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199609086.

- Robertson, William (1877). The Life and Times of the right hon. John Bright. Oxford University.

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council (n.d.). Metropolitan Rochdale Official Guide. London: Ed. J. Burrow & Co. Limited.

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council (1985). Official Guide to Rochdale Metropolitan Borough. Gloucester: The British Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7140-2276-5.

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council (2006). Rochdale Borough Unitary Development Plan (PDF). Rochdale: Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council.

- Royal Society of Medicine (1915). Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. Vol. 8: Part 2. Royal Society of Medicine.

- Sellers, Gladys (1991). Walking the South Pennines. Cicerone Press. ISBN 978-1-85284-041-9.

- Simpson, Ludi; Ahmed, Sameera; Phillips, Debbie (2008). Oldham and Rochdale: race, housing and community cohesion (PDF). The University of Manchester.

- Taylor, Rebe Prestwich (1956). Rochdale Retrospect, a Handbook. Rochdale Corporation.

- Trinder, Barrie Stuart (1982). The Making of the Industrial Landscape. Dent. ISBN 9780460044271.

- Trower, Shelley (2011). Place, Writing, and Voice in Oral History. Springer. ISBN 9780230339774.

- University of Manchester Archaeological Unit; Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit (1996). Castleshaw and Piethorn - North West Water Landholding: Archaeological Survey (PDF). Manchester: University of Manchester.

- Waller, Robert; Criddle, Byron (2002). The Almanac of British Politics. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415268332.

- Waugh, Edwin (1855). Sketches of Lancashire life and localities. James Galt.

External links

- www.ellenroad.org.uk, Ellenroad Steam Museum website.

- www.milnrow.co.uk, a website about Milnrow.

- milnrow.org, the website about Milnrow Evangelical Church.

- www.milnrowband.org.uk, past, present and future of the Milnrow Band.

- www.link4life.org, the history of Milnrow and Newhey.