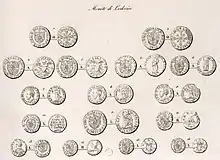

Mirandola mint

The Mirandola mint (Italian: zecca della Mirandola), also known as the mint of the Pico della Mirandola, was the mint of the Duchy of Mirandola.

.jpg.webp) The city of Mirandola in 18th century | |

| Type | Coin mint |

|---|---|

| Industry | Coin production |

| Founded | 1515 |

| Defunct | 1708 |

| Headquarters | Mirandola, Duchy of Mirandola |

Area served | Duchy of Mirandola |

| Products | Coins |

| Owner | Duchy of Mirandola |

The activity of the mint, which minted over 500 types of coins, began in Mirandola in 1515 and ended with the exile of the Pico family from the Duchy of Mirandola in the early 18th century, after the return of the imperials following the French siege of Mirandola in 1705.

The royal coins collection of King Vittorio Emanuele III, now housed in the National Roman Museum in Rome, and the collection in the Civic Museum of Mirandola are the largest collections of coins minted in the ancient State of Mirandola.

History

Coinage under John Francis II (1515-1533)

The birth of the Mirandola mint dates back to a few years after the siege of Mirandola by pope Julius II, when in 1515 the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Maximilian I of Hapsburg, granted the Lord Giovanni Francesco Pico della Mirandola permission to mint coins:[1] in fact, the first coins in which the Pico coat of arms is depicted next to the imperial eagle date back to that year.

Concedimus et largimur ius cudendi monetam tam auream quam argenteam et aenam, et cuiuscumque alterius materiae et formae, dummodo tamen debito et iusto pondere et modo, uti fieri debet, faciat, et cum hac conditione quod in eo Aquila imperialis insculpatur.

We grant and give away the right to strike coins of gold, silver, bronze, and any other material and form, provided, however, that they be of due and proper weight and in the manner in which it should be done, and with this condition that the imperial eagle be engraved upon them.

— Maximilian I of Habsburg, Diploma (1515)

In 1524, during the period of the Mirandola witch-hunt, the first gold coins were minted with the effigy St Francis of Assisi with the stigmata, but a scandal broke out when it was discovered that doubloons e ducats were gold low-grade.[2] Giovanna Carafa, wife of Gianfrancesco Pico and defined as a "tyrannically avaricious woman",[3] was accused by the partisans of her nephew Galeotto II Pico of having forged the gold coins out of resentment towards her husband, but she blamed the Jewish mintmaster Santo di Bochali (a mere executor of the sovereign's wishes), who had all his goods confiscated[4] and was beheaded in the main square by order of Giovanfrancesco to save his wife's reputation.[5]

Unfortunately, the reputation of Mirandola's gold coinage was seriously compromised and it was necessary to switch from ducats to the minting of gold shields. The silver coinage of Giovanni Francesco II Pico is very rare (since the mintmaster was more interested in profiting from the gold coins), while the copper coinage was characterised by the issue of bagattini of reduced weight compared to other mints.[6]

Coinage under Galeotto II (1533-1550)

After the murder of Giovanni Francesco in 1533, his successor Galeotto II Pico della Mirandola minted a few coins: the golden scudo and the silver bianco (worth half of the gold coin), as well as muraiole, sesini and quattrini.[6]

Coinage under Ludovico II (1550-1568)

The abundant coinage of Ludovico II Pico della Mirandola, who came to power in 1550, was marked by the 1551 siege of Mirandola, during which the Mirandola fortress managed to repel the besieging papal army sent by Pope Julius III: the coins are in fact characterised by allegories recalling the defeat of the pope (war trophies, armour with olive branches, waves breaking against a rock, the personification of Victoria carrying a light in her right hand instead of blowing the trumpet of victory) and were minted in large numbers to repay the costs of the war.[6]

Coinage under Galeotto III (1568-1590)

During the reign of Galeotto III Pico della Mirandola, the Mirandola mint went into crisis, as well as the mints of Ferrara, Mantua and Modena (while the mint of Reggio Emilia closed in 1572): only a very rare gold shield is known from this period. During the very short reign of Federico II Pico della Mirandola (1596-1602) no new minting dies were made.[6]

Coinage under Alessandro I (1602-1637)

The advent of Alessandro I Pico della Mirandola in 1602 marked the maximum splendour of the State of Mirandola, which a few years later, in 1617, obtained the title of duchy by Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor,[7] after the payment of 100,000 florins; this sum of money was so huge that it forced the Pico family to reopen the mint. The coinage was then entrusted to the Genoese Giovanni Agostino Rivarola (former mintmaster of Correggio, Ferrara, Massa, Parma and Tresana), who minted doubles and ducatons of excellent alloy, which allowed a wide diffusion, but also scarcer coins (called bagiane in a derogatory way) for the local economy, as well as other coins that imitated those of Modena and Mantua (called, respectively, giorgino and possidonio). Unfortunately, as had already happened in the past, Agostino Rivarola began to mint a great many counterfeit and fake coins (dicken with the effigy of St Possidonio, groschen and florins), destined above all for northern Europe, which was suffering from a severe economic crisis caused by the Thirty Years' War and epidemics. In 1623, Rivarola was arrested for counterfeiting and sentenced to Correggio (whose fiefdom was taken from Prince Siro, as he was considered an accomplice of the mintmaster) and Mirandola, where the mint was closed for several years.

.jpg.webp)

Around 1630 the Mirandola mint was reopened and entrusted to the Jew Jacob Padua, who after his conversion to Christianity called himself Gian Francesco Manfredi (he was sentenced to death too for forgery in Modena). In this period a great number of quattrini were minted in pure copper, which were publicly banned by the municipality of Bologna in 1636, as they were less heavy and valuable than the original Bolognese quattrino.

On 21 January 1634, in Turin, Victor Amadeus I, Duke of Savoy issued the Nuovo bando delle monete basse di zeche forastiere, e specialmente delle improntate al piede del presente ordine: although this ban does not expressly mention the coins of the Mirandola mint among those banned, it does depict a coin bearing the coat of arms of Duke Alessandro I Pico at the bottom..[8][9]

Coinage during Alessandro II (1637-1691)

On 21 February 1639, Ferdinand III, Holy Roman Emperor sent a confirmation diploma to new duke Alessandro II Pico della Mirandola to continue minting the coins, although it is known that several Dutch-type lion thalers had already been minted in 1638. The Pico mint was entrusted to the Jew Elia Teseo, whose initials appear on the one-lira and one-horse coins of 1669 (very common and used until 1731). In the meantime, the municipality of Bologna continued to issue proclamations (in 1646, 1650 and 1681) prohibiting the sending of Mirandola quattrini, which were always of a weight less than bolognini. Also in this period, several counterfeit coins are known, such as the soldino of Milan (1672) and the sesino of Modena.[10]

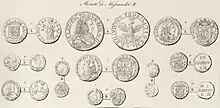

Coinage during Francesco Maria II (1691-1708)

.jpg.webp)

It is believed that towards the end of the 17th century the Mirandola mint was no longer active, as were other small Italian mints.[10]

The last coinage in Mirandola took place under the short-lived reign of the last duke Francesco Maria II Pico, or rather by the imperial military garrison during the siege of the French at Mirandola in 1704-1705 during the War of the Spanish Succession. In October 1704, in fact, the Caesarean commander Dominik von Königsegg-Rothenfels had to provide for the minting of new coins, as he had to meet the costs of the siege; however, not being able to manufacture new coinage, the Alemanni decided to reuse the old coinage with the effigy of Alexander II Pico (who had died in 1691) and inserting the year 1704.[10] This currency was not accepted by the population, so much so that the imperial authority had to issue a decree to enforce the use and acceptance of these coins: With the fall of the Pico family, accused of felony by the Emperor and exiled for having sided with the French, the mint of Mirandola definitively ended its history; however, the coins of Mirandola continued to be mentioned in proclamations and tariffs since, in an economy that was very poor at the time, the circulating currency was always the same.[10] In a Grida e tariffa sopra le monete issued in Modena at the end of December 1731, the "Pezzo della Lira della Mirandola" is still mentioned.

References

- Antonio Castellani (2015-02-16). "Cinque secoli fa, la zecca di Mirandola". Archived from the original on 2017-10-27.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Lucia Travaini (2019-06-09). "Mirandola 1524: la frode dell'oro".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Giambattista Corniani (1832). I secoli della letteratura italiana dopo il suo risorgimento. Vol. 1. Milano: coi tipi di Vincenzo Ferrario. p. 244.

- Tomasino de Bianchi detto il Lancelotti (2 July 1524). "Cronaca".

Venne nova in Modena come el Sr Zan Francesco Pico dala Mirandola ha fato mozare la testa a M.ro Santo di Bochali dela Mirandola suo magistro di cecha e questo per havere fato deli dupioni et ducati de oro falsi et ha confiscato li soi beni ala restitution de quelle persone che hanno de ditto oro falso e che vadano ala Mirandola che li farà satisfare ogni homo del suo danno; el non ge ha mai voluto provedere sino a tanto tuta Italia non è stata amorbata de dito oro, in li quali era li boni quasi cusì cativi como li cativi, per modo che da sol. 75 sono andati a sol. 73 e pochi li voleno e non se trova moneta in Modena né ducati de bon stampi, perché sono guasti e fati de diti ducati dela Mirandola.

- Pompeo Litta (1835). "Famiglie celebri di Italia. Pico della Mirandola". Torino: 4.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - (Bellesia, 2015 (I)).

- Roberto Ganganelli (12 July 2016). "Parole e monete: il "piede sicuro" di Alessandro I Pico della Mirandola". Il giornale della numismatica. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- "Nuovo bando delle monete basse di zeche forastiere, e specialmente delle improntate al piede del presente ordine". Torino: per Bartolomeo Zappata Libraro di S. A. R. 1681: 349–350. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - (Bellesia, 2015 (II)).

- (Bellesia, 2015 (III)).

Bibliography

- Corpus Nummorum Italicorum (CNI). Vol. IX Emilia (1ª parte). 1926.

- Lorenzo Bellesia (1995). La zecca dei Pico. Mirandola: Centro intinternazionale di cultura "Giovanni Pico dela Mirandola".

- Lorenzo Bellesia (January 2015). La zecca di Mirandola - Parte I - Da Gian Francesco II Pico (1499-1533) a Galeotto III Pico (1568-1597) (PDF). Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato.

- Lorenzo Bellesia (February 2015). La zecca di Mirandola - Parte II - Alessandro I Pico (1602-1637) (PDF). Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato.

- Lorenzo Bellesia (March 2015). La zecca di Mirandola - Parte III - Alessandro II Pico (1637-1691) e Francesco Maria Pico (1691-1706) (PDF). Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato.

- Vicenzo Bellini (1755). De monetis Italiae medii aevi hactenus non evulgatis quae in suo musaeo servantur: una cum earundem iconibus dissertatio (in Latin). Ferrara: Typis Bernardini Pomatelli. pp. 71–72.

- Vicenzo Bellini (1774). De monetis Italiae medii aevi hactenus non evulgatis, quae in patrio museo servantur, una cum earundem iconibus, novissima dissertatio (in Latin). Ferrara: typis Joseph Rinaldi. pp. 42–47, 50.

- Vilmo Cappi (1995). Le monete dei Pico. Cassa di Risparmio di Mirandola.

- Vilmo Cappi, ed. (1963). La zecca di casa Pico: timbri ed incisioni mirandolesi, medaglie. Modena: Coop. Tipografi.

- Carlo Kunz (1881–1882). "Monete di Mirandola". VIII. Trieste: Tipografia di Lodovico Herrmanstofer: 1–20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Pompeo Litta Biumi (1819). Pico della Mirandola.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Lucia Travaini, ed. (2011). Le zecche Italiane fino all'Unità. IPZS.

- A. Varesi (1998). Monete Italiane Regionali - Emilia. Pavia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

See also

External links

- "Monete della zecca di Mirandola". Retrieved 2017-10-27.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Roberto Ganganelli (2017-08-03). "Parole e monete: un misterioso motto sulle monete di Mirandola". Archived from the original on 2017-10-27.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)