Misanthropy

Misanthropy is the general hatred, dislike, or distrust of the human species, human behavior, or human nature. A misanthrope or misanthropist is someone who holds such views or feelings. Misanthropy involves a negative evaluative attitude toward humanity that is based on humankind's flaws. Misanthropes hold that these flaws characterize all or at least the great majority of human beings. They claim that there is no easy way to rectify them short of a complete transformation of the dominant way of life. Various types of misanthropy are distinguished in the academic literature based on what attitude is involved, at whom it is directed, and how it is expressed. Either emotions or theoretical judgments can serve as the foundation of the attitude. It can be directed at all humans without exception or exclude a few idealized people. In this regard, some misanthropes condemn themselves while others consider themselves superior to everyone else. Misanthropy is sometimes associated with a destructive outlook aiming to hurt other people or an attempt to flee society. Other types of misanthropic stances include activism by trying to improve humanity, quietism in the form of resignation, and humor mocking the absurdity of the human condition.

The negative misanthropic outlook is based on different types of human flaws. Moral flaws are often seen as the main factor. They include cruelty, indifference to the suffering of others, selfishness, injustice, and greed. They may result in harm to humans and animals, like genocides and factory farming of livestock. Other flaws include intellectual flaws, like dogmatism and cognitive biases, as well as aesthetic flaws concerning ugliness and lack of sensitivity to beauty. Many debates in the academic literature discuss whether misanthropy is a valid viewpoint and what its implications are. Proponents of misanthropy usually point to human flaws and the harm they have caused as a sufficient reason for condemning humanity. Critics have responded to this line of thought by claiming that severe flaws concern only a few extreme cases, like mentally ill perpetrators, but not humanity at large. Another objection is based on the claim that humans also have virtues besides their flaws and that a balanced evaluation might be overall positive. A further criticism rejects misanthropy because of its association with hatred, which may lead to violence, and because it may make people friendless and unhappy. Defenders of misanthropy have responded by claiming that this applies only to some forms of misanthropy but not to misanthropy in general.

A related issue concerns the question of the psychological and social factors that cause people to become misanthropes. They include socio-economic inequality, living under an authoritarian regime, and undergoing personal disappointments in life. Misanthropy is relevant in various disciplines. It has been discussed and exemplified by philosophers throughout history, like Heraclitus, Diogenes, Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Friedrich Nietzsche. Misanthropic outlooks form part of some religious teachings discussing the deep flaws of human beings, like the Christian doctrine of original sin. Misanthropic perspectives and characters are also found in literature and popular culture. They include William Shakespeare's portrayal of Timon of Athens, Molière's play The Misanthrope, and Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift. Misanthropy is closely related to but not identical to philosophical pessimism. Some misanthropes promote antinatalism, the view that humans should abstain from procreation.[1][2]

Definition

Misanthropy is traditionally defined as hatred or dislike of humankind.[3][4] The word originated in the 17th century and has its roots in the Greek words μῖσος mīsos 'hatred' and ἄνθρωπος ānthropos 'man, human'.[5][6] In contemporary philosophy, the term is usually understood in a wider sense as a negative evaluation of humanity as a whole based on humanity's vices and flaws.[7][8] This negative evaluation can express itself in various forms, hatred being only one of them. In this sense, misanthropy has a cognitive component based on a negative assessment of humanity and is not just a blind rejection.[7][8][9] Misanthropy is usually contrasted with philanthropy, which refers to the love of humankind and is linked to efforts to increase human well-being, for example, through charitable aid or donations. Both terms have a range of meanings and do not necessarily contradict each other. In this regard, the same person may be a misanthrope in one sense and a philanthrope in another sense.[10][11][12]

One central aspect of all forms of misanthropy is that their target is not local but ubiquitous. This means that the negative attitude is not just directed at some individual persons or groups but at humanity as a whole.[13][14][15] In this regard, misanthropy is different from other forms of negative discriminatory attitudes directed at a particular group of people. This distinguishes it from the intolerance exemplified by racists, misogynists, and misandrists, which hold a negative attitude toward certain races or genders.[9][16][17][9] According to literature theorist Andrew Gibson, misanthropy does not need to be universal in the sense that a person literally dislikes every human being. Instead, it depends on the person's horizon. For instance, a villager who loathes every other villager without exception is a misanthrope if their horizon is limited to only this village.[18]

Both misanthropes and their critics agree that negative features and failings are not equally distributed, i.e. that the vices and bad traits are exemplified much more strongly in some than in others. But for misanthropy, the negative assessment of humanity is not based on a few extreme and outstanding cases: it is a condemnation of humanity as a whole that is not just directed at exceptionally bad individuals but includes regular people as well.[7][14] Because of this focus on the ordinary, it is sometimes held that these flaws are obvious and trivial but people may ignore them due to intellectual flaws. Some see the flaws as part of human nature as such.[19][20][21] Others also base their view on non-essential flaws, i.e. what humanity has come to be. This includes flaws seen as symptoms of modern civilization in general. Nevertheless, both groups agree that the relevant flaws are "entrenched". This means that there is either no or no easy way to rectify them and nothing short of a complete transformation of the dominant way of life would be required if that is possible at all.[22][23]

Types

Various types of misanthropy are distinguished in the academic literature. They are based on what attitude is involved, how it is expressed, and whether the misanthropes include themselves in their negative assessment.[24][25][26] The differences between them often matter for assessing the arguments for and against misanthropy.[27][28] An early categorization suggested by Immanuel Kant distinguishes between positive and negative misanthropes. Positive misanthropes are active enemies of humanity. They wish harm to other people and undertake attempts to hurt them in one form or another. Negative misanthropy, by contrast, is a form of peaceful anthropophobia that leads people to isolate themselves. They wish others well despite seeing serious flaws in them. Kant associates negative misanthropy with moral disappointment due to previous negative experiences with others.[24][29]

Another distinction focuses on whether the misanthropic condemnation of humanity is only directed at other people or at everyone including oneself. In this regard, self-inclusive misanthropes are consistent in their attitude by including themselves in their negative assessment. This type is contrasted with self-aggrandizing misanthropes, who either implicitly or explicitly exclude themselves from the general condemnation and see themselves instead as superior to everyone else.[25][30] In this regard, it may be accompanied by an exaggerated sense of self-worth and self-importance.[31] According to literature theorist Joseph Harris, the self-aggrandizing type is more common. He states that this outlook seems to undermine its own position by constituting a form of hypocrisy.[32] A closely related categorization developed by Irving Babbitt distinguishes misanthropes based on whether they allow exceptions in their negative assessment. In this regard, misanthropes of the naked intellect regard humanity as a whole as hopeless. Tender misanthropes exclude a few idealized people from their negative evaluation. Babbitt cites Rousseau and his fondness for natural uncivilized man as an example of tender misanthropy and contrasts it with Jonathan Swift's thorough dismissal of all of humanity.[33][34]

A further way to categorize forms of misanthropy is in relation to the type of attitude involved toward humanity. In this regard, philosopher Toby Svoboda distinguishes the attitudes of dislike, hate, contempt, and judgment. A misanthrope based on dislike harbors a distaste in the form of negative feelings toward other people.[13] Misanthropy focusing on hatred involves an intense form of dislike. It includes the additional component of wishing ill upon others and at times trying to realize this wish.[35] In the case of contempt, the attitude is not based on feelings and emotions but on a more theoretical outlook. It leads misanthropes to see other people as worthless and look down on them while excluding themselves from this assessment.[36] If the misanthropic attitude has its foundation in judgment, it is also theoretical but does not distinguish between self and others. It is the view that humanity is in general bad without implying that the misanthrope is in any way better than the rest.[37] According to Svoboda, only misanthropy based on judgment constitutes a serious philosophical position. He holds that misanthropy focusing on contempt is biased against other people while misanthropy in the form of dislike and hate is difficult to assess since these emotional attitudes often do not respond to objective evidence.[38]

Misanthropic forms of life

Misanthropy is usually not restricted to a theoretical opinion but involves an evaluative attitude that calls for a practical response. It can express itself in different forms of life. They come with different dominant emotions and practical consequences for how to lead one's life.[7][39] These responses to misanthropy are sometimes presented through simplified archetypes that may be too crude to accurately capture the mental life of any single person. Instead, they aim to portray common attitudes among groups of misanthropes. The two responses most commonly linked to misanthropy involve either destruction or fleeing from society. The destructive misanthrope is said to be driven by a hatred of humankind and aims at tearing it down, with violence if necessary.[7][40] For the fugitive misanthrope, fear is the dominant emotion and leads the misanthrope to seek a secluded place in order to avoid the corrupting contact with civilization and humanity as much as possible.[7][9]

The contemporary misanthropic literature has also identified further less-known types of misanthropic lifestyles.[7] The activist misanthrope is driven by hope despite their negative appraisal of humanity. This hope is a form of meliorism based on the idea that it is possible and feasible for humanity to transform itself and the activist tries to realize this ideal.[7][41] A weaker version of this approach is to try to improve the world incrementally to avoid some of the worst outcomes without the hope of fully solving the basic problem.[42] Activist misanthropes differ from quietist misanthropes, who take a pessimistic approach toward what the person can do for bringing about a transformation or significant improvements. In contrast to the more drastic reactions of the other responses mentioned, they resign themselves to quiet acceptance and small-scale avoidance.[43][7] A further approach is focused on humor based on mockery and ridicule at the absurdity of the human condition. An example is that humans hurt each other and risk future self-destruction for trivial concerns like a marginal increase in profit. This way, humor can act both as a mirror to portray the terrible truth of the situation and as its palliative at the same time.[44]

Forms of human flaws

A core aspect of misanthropy is that its negative attitude toward humanity is based on human flaws.[45][7] Various misanthropes have provided extensive lists of flaws, including cruelty, greed, selfishness, wastefulness, dogmatism, self-deception, and insensitivity to beauty.[46][47][7] These flaws can be categorized in many ways. It is often held that moral flaws constitute the most serious case.[23][48] Other flaws discussed in the contemporary literature include intellectual flaws, aesthetic flaws, and spiritual flaws.[49][23]

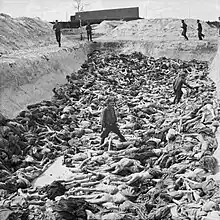

Moral flaws are usually understood as tendencies to violate moral norms or as mistaken attitudes toward what is the good.[50][51] They include cruelty, indifference to the suffering of others, selfishness, moral laziness, cowardice, injustice, greed, and ingratitude. The harm done because of these flaws can be divided into three categories: harm done directly to humans, harm done directly to other animals, and harm done indirectly to both humans and animals by harming the environment. Examples of these categories include the Holocaust, factory farming of livestock, and pollution causing climate change.[52][23][53] In this regard, it is not just relevant that human beings cause these forms of harm but also that they are morally responsible for them. This is based on the idea that they can understand the consequences of their actions and could act differently. However, they decide not to, for example, because they ignore the long-term well-being of others in order to get short-term personal benefits.[54]

Intellectual flaws concern cognitive capacities. They can be defined as what leads to false beliefs, what obstructs knowledge, or what violates the demands of rationality. They include intellectual vices, like arrogance, wishful thinking, and dogmatism. Further examples are stupidity, gullibility, and cognitive biases, like the confirmation bias, the self-serving bias, the hindsight bias, and the anchoring bias.[55][56][50] Intellectual flaws can work in tandem with all kinds of vices: they may deceive someone about having a vice. This prevents the affected person from addressing it and improving themselves, for instance, by being mindless and failing to recognize it. They also include forms of self-deceit, wilful ignorance, and being in denial about something.[57][58] Similar considerations have prompted some traditions to see intellectual failings, like ignorance, as the root of all evil.[59][60][61]

Aesthetic flaws are usually not given the same importance as moral and intellectual flaws, but they also carry some weight for misanthropic considerations. These flaws relate to beauty and ugliness. They concern ugly aspects of human life itself, like defecation and aging. Other examples are ugliness caused by human activities, like pollution and litter, and inappropriate attitudes toward aesthetic aspects, like being insensitive to beauty.[62][63][23]

Causes

Various psychological and social factors have been identified in the academic literature as possible causes of misanthropic sentiments. The individual factors by themselves may not be able to fully explain misanthropy but can show instead how it becomes more likely.[28] For example, disappointments and disillusionments in life can cause a person to adopt a misanthropic outlook.[64][65] In this regard, the more idealistic and optimistic the person initially was, the stronger this reversal and the following negative outlook tend to be.[64] This type of psychological explanation is found as early as Plato's Phaedo. In it, Socrates considers a person who trusts and admires someone without knowing them sufficiently well. He argues that misanthropy may arise if it is discovered later that the admired person has serious flaws. In this case, the initial attitude is reversed and universalized to apply to all others, leading to general distrust and contempt toward other humans. Socrates argues that this becomes more likely if the admired person is a close friend and if it happens more than once.[66][67] This form of misanthropy may be accompanied by a feeling of moral superiority in which the misanthrope considers themselves to be better than everyone else.[64]

Other types of negative personal experiences in life may have a similar effect. Andrew Gibson uses this line of thought to explain why some philosophers became misanthropes. He uses the example of Thomas Hobbes to explain how a politically unstable environment and the frequent wars can foster a misanthropic attitude. Regarding Arthur Schopenhauer, he states that being forced to flee one's home at an early age and never finding a place to call home afterward can have a similar effect.[28][68] Another psychological factor concerns negative attitudes toward the human body, especially in the form of general revulsion from sexuality.[69][28]

Besides the psychological causes, some wider social circumstances may also play a role. Generally speaking, the more negative the circumstances are, the more likely misanthropy becomes.[70][28] For instance, according to political scientist Eric M. Uslaner, socio-economic inequality in the form of unfair distribution of wealth increases the tendency to adopt a misanthropic perspective. This has to do with the fact that inequality tends to undermine trust in the government and others. Uslaner suggests that it may be possible to overcome or reduce this source of misanthropy by implementing policies that build trust and promote a more equal distribution of wealth.[28][71] The political regime is another relevant factor. This specifically concerns authoritarian regimes using all means available to repress their population and stay in power.[72][73] For example, it has been argued that the severe forms of repression of the Ancien Régime in the late 17th century made it more likely for people to adopt a misanthropic outlook because their freedom was denied.[28][74] Democracy may have the opposite effect since it allows more personal freedom due to its more optimistic outlook on human nature. [72][73]

Empirical studies often use questions related to trust in other people to measure misanthropy. This concerns specifically whether the person believes that others would be fair and helpful.[75][76] In an empirical study on misanthropy in American society, Tom W. Smith concludes that factors responsible for an increased misanthropic outlook are low socioeconomic status, being from racial and ethnic minorities, and having experienced recent negative events in one's life. In regard to religion, misanthropy is higher for people who do not attend church and for fundamentalists. Some factors seem to play no significant role, like gender, having undergone a divorce, and never having been married.[75] Another study by Morris Rosenberg finds that misanthropy is linked to certain political outlooks. They include being skeptical about free speech and a tendency to support authoritarian policies. This concerns, for example, tendencies to suppress political and religious liberties.[75][76]

Arguments

Various discussions in the academic literature concern the question of whether misanthropy is an accurate assessment of humanity and what the consequences of adopting it are. Many proponents of misanthropy focus on human flaws together with examples of when they exercise their negative influences. They argue that these flaws are so severe that misanthropy is an appropriate response.[77]

Special importance in this regard is usually given to moral faults.[78][79][7] This is based on the idea that humans do not merely cause a great deal of suffering and destruction but are also morally responsible for them. The reason is that they are intelligent enough to understand the consequences of their actions and could potentially make balanced long-term decisions instead of focusing on personal short-term gains.[54]

Proponents of misanthropy sometimes focus on extreme individual manifestations of human flaws, like mass killings ordered by dictators. Others emphasize that the problem is not limited to a few cases, for example, that many ordinary people are complicit in their manifestation by supporting the political leaders committing them.[80] A closely related argument is to claim that the underlying flaws are there in everyone, even if they reach their most extreme manifestation only in a few.[7] Another approach is to focus not on the grand extreme cases but on the ordinary small-scale manifestations of human flaws in everyday life, such as lying, cheating, breaking promises, and being ungrateful.[81][82]

Some arguments for misanthropy focus not only on general tendencies but on actual damage caused by humans in the past.[53][83][84] This concerns, for instance, damages done to the ecosystem, like ecological catastrophes resulting in mass extinctions.[85]

Criticism

Various theorists have criticized misanthropy. Some opponents acknowledge that there are extreme individual manifestations of human flaws, like mentally ill perpetrators, but claim that these cases do not reflect humanity at large and cannot justify the misanthropic attitude. For instance, while there are cases of extreme human brutality, like the mass killings committed by dictators and their forces, listing such cases is not sufficient for condemning humanity at large.[7][86]

Some critics of misanthropy acknowledge that humans have various flaws but state that they present just one side of humanity while evaluative attitudes should take all sides into account. This line of thought is based on the idea that humans possess equally important virtues that make up for their shortcomings.[87] For example, accounts that focus only on the great wars, cruelties, and tragedies in human history ignore its positive achievements in the sciences, arts, and humanities.[88]

Another explanation given by critics is that the negative assessment should not be directed at humanity but at some social forces. These forces can include capitalism, racism, religious fundamentalism, or imperialism.[89] Supporters of this argument would adopt an opposition to one of these social forces rather than a misanthropic opposition to humanity.[90]

Some objections to misanthropy are based not on whether this attitude appropriately reflects the negative value of humanity but on the costs of accepting such a position. The costs can affect both the individual misanthrope and the society at large. This is especially relevant if misanthropy is linked to hatred, which may turn easily into violence against social institutions and other humans and may result in harm.[91] Misanthropy may also deprive the person of most pleasures by making them miserable and friendless.[92]

Another form of criticism focuses more on the theoretical level and claims that misanthropy is an inconsistent and self-contradictory position.[93][28] An example of this inconsistency is the misanthrope's tendency to denounce the social world while still being engaged in it and being unable to fully leave it behind.[94] This criticism applies specifically to misanthropes who exclude themselves from the negative evaluation and look down on others with contempt from an arrogant position of inflated ego but it may not apply to all types of misanthropy.[95][96][30] A closely related objection is based on the claim that misanthropy is an unnatural attitude and should therefore be seen as an aberration or a pathological case.[97]

In various disciplines

History of philosophy

Misanthropy has been discussed and exemplified by philosophers throughout history. One of the earliest cases was the pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus. He is often characterized as a solitary person who is not fond of social interactions with others. A central factor to his negative outlook on human beings was their lack of comprehension of the true nature of reality. This concerns especially cases in which they remain in a state of ignorance despite having received a thorough explanation of the issue in question.[98][99][100] Another early discussion is found in Plato's Phaedo, where misanthropy is characterized as the result of frustrated expectations and excessively naïve optimism.[101][66][67]

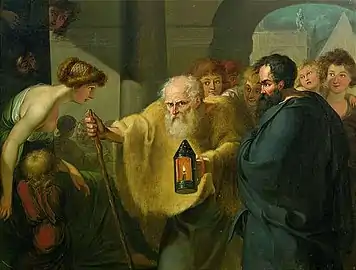

Various reflections on misanthropy are also found in the cynic school of philosophy. There it is argued, for instance, that humans keep on reproducing and multiplying the evils they are attempting to flee. An example given by the first-century philosopher Dio Chrysostom is that humans move to cities to defend themselves against outsiders but this process thwarts their initial goal by leading to even more violence due to high crime rates within the city. Diogenes is a well-known cynic misanthrope. He saw other people as hypocritical and superficial. He openly rejected all kinds of societal norms and values, often provoking others by consciously breaking conventions and behaving rudely.[104][28][105]

Thomas Hobbes is an example of misanthropy in early modern philosophy. His negative outlook on humanity is reflected in many of his works. For him, humans are egoistic and violent: they act according to their self-interest and are willing to pursue their goals at the expense of others. In their natural state, this leads to a never-ending war in which "every man to every man ... is an enemy". He saw the establishment of an authoritative state characterized by the strict enforcement of laws to maintain order as the only way to tame the violent human nature and avoid perpetual war.[106][107][108]

A further type of misanthropy is found in Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He idealizes the harmony and simplicity found in nature and contrasts them with the confusion and disorder found in humanity, especially in the form of society and institutions.[109][110][111] For instance, he claims that "Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains".[112][113] This negative outlook was also reflected in his lifestyle: he lived solitary and preferred to be with plants rather than humans.[114]

Arthur Schopenhauer is often mentioned as a prime example of misanthropy.[115][116] According to him, everything in the world, including humans and their activities, is an expression of one underlying will. This will is blind, which causes it to continuously engage in futile struggles. On the level of human life, this "presents itself as a continual deception" since it is driven by pointless desires. They are mostly egoistic and often result in injustice and suffering to others. Once they are satisfied, they only give rise to new pointless desires and more suffering.[117][118][119] In this regard, Schopenhauer dismisses most things that are typically considered precious or meaningful in human life, like romantic love, individuality, and liberty.[120] He holds that the best response to the human condition is a form of asceticism by denying the expression of the will. This is only found in rare humans and "the dull majority of men" does not live up to this ideal.[121]

Friedrich Nietzsche, who was strongly influenced by Schopenhauer, is also often cited as an example of misanthropy. He saw man as a decadent and "sick animal" that shows no progress over other animals.[122][123][124] He even expressed a negative attitude toward apes since they are more similar to human beings than other animals, for example, with regard to cruelty.[125] For Nietzsche, a noteworthy flaw of human beings is their tendency to create and enforce systems of moral rules that favor weak people and suppress true greatness.[123][126] He held that the human being is something to be overcome and used the term Übermensch to describe an ideal individual who has transcended traditional moral and societal norms.[127][128]

Religion

Some misanthropic views are also found in religious teachings. In Christianity, for instance, this is linked to the sinful nature of humans and the widespread manifestation of sin in everyday life.[129] Common forms of sin are discussed in terms of the seven deadly sins. Examples are an excessive sense of self-importance in the form of pride and strong sexual cravings constituting lust. They also include the tendency to follow greed for material possessions as well as being envious of the possessions of others.[130] According to the doctrine of original sin, this flaw is found in every human being since the doctrine states that human nature is already tainted by sin from birth by inheriting it from Adam and Eve's rebellion against God's authority.[129][131] John Calvin's theology of Total depravity has been described by some theologians as misanthropic.[132][133][134]

Misanthropic perspectives can also be discerned in various Buddhist teachings. For example, Buddha had a negative outlook on the widespread flaws of human beings, including lust, hatred, delusion, sorrow, and despair.[135] These flaws are identified with some form of craving or attachment (taṇhā) and cause suffering (dukkha).[136][137] Buddhists hold that it is possible to overcome these failings in the process of achieving Buddhahood or enlightenment. However, this is seen as a rare achievement in one lifetime. In this regard, most human beings carry these deep flaws with them throughout their lives.[138]

However, there are also many religious teachings opposed to misanthropy, such as the emphasis on kindness and helping others. In Christianity, this is found in the concept of agape, which involves selfless and unconditional love in the form of compassion and a willingness to help others.[139] Buddhists see the practice of loving kindness (metta) as a central aspect that implies a positive intention of compassion and the expression of kindness toward all sentient beings.[140][141]

Literature and popular culture

Many examples of misanthropy are also found in literature and popular culture. Timon of Athens by William Shakespeare is a famous portrayal of the life of the Ancient Greek Timon, who is widely known for his extreme misanthropic attitude. Shakespeare depicts him as a wealthy and generous gentleman. However, he becomes disillusioned with his ungrateful friends and humanity at large. This way, his initial philanthropy turns into an unrestrained hatred of humanity, which prompts him to leave society in order to live in a forest.[142][143] Molière's play The Misanthrope is another famous example. Its protagonist, Alceste, has a low opinion of the people around him. He tends to focus on their flaws and openly criticizes them for their superficiality, insincerity, and hypocrisy. He rejects most social conventions and thereby often offends others, for example, by refusing to engage in social niceties like polite small talk.[144][145][146]

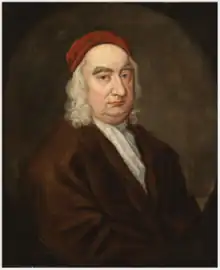

The author Jonathan Swift had a reputation for being misanthropic. In some statements, he openly declares that he hates and detests "that animal called man".[147] Misanthropy is also found in many of his works. An example is Gulliver's Travels, which tells the adventures of the protagonist Gulliver, who journeys to various places, like an island inhabited by tiny people and a land ruled by intelligent horses. Through these experiences of the contrast between humans and other species, he comes to see more and more the deep flaws of humanity, leading him to develop a revulsion toward other human beings.[148][149] Ebenezer Scrooge from Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol is an often-cited example of misanthropy. He is described as a cold-hearted, solitary miser who detests Christmas. He is greedy, selfish, and has no regard for the well-being of others.[150][151][152] Other writers associated with misanthropy include Gustave Flaubert and Philip Larkin.[153][154]

The Joker from the DC Universe is an example of misanthropy in popular culture. He is one of the main antagonists of Batman and acts as an agent of chaos. He believes that people are selfish, cruel, irrational, and hypocritical. He is usually portrayed as a sociopath with a twisted sense of humor who uses violent means to expose and bring down organized society.[155][156][157]

Related concepts

Philosophical pessimism

Misanthropy is closely related but not identical to philosophical pessimism. Philosophical pessimism is the view that life is not worth living or that the world is a bad place, for example, because it is meaningless and full of suffering.[158][159] This view is exemplified by Arthur Schopenhauer and Philipp Mainländer.[160] Philosophical pessimism is often accompanied by misanthropy if the proponent holds that humanity is also bad and partially responsible for the negative value of the world. However, the two views do not require each other and can be held separately.[7][161] A non-misanthropic pessimist may hold, for instance, that humans are just victims of a terrible world but not to blame for it. Eco-misanthropists, by contrast, may claim that the world and its nature are valuable but that humanity exerts a negative and destructive influence.[7][162]

Antinatalism and human extinction

Humanity is a moral disaster. There would have been much less destruction had we never evolved. The fewer humans there are in the future, the less destruction there will still be.

—David Benatar, "The Misanthropic Argument for Anti-natalism"[79]

Antinatalism is the view that coming into existence is bad and that humans have a duty to abstain from procreation.[163][164] A central argument for antinatalism is called the misanthropic argument. It sees the deep flaws of humans and their tendency to cause harm as a reason for avoiding the creation of more humans.[165][166] These harms include wars, genocides, factory farming, and damages done to the environment.[167][168] This argument contrasts with philanthropic arguments, which focus on the future suffering of the human about to come into existence. They argue that the only way to avoid their future suffering is to prevent them from being born.[165][166][42] The Voluntary Human Extinction Movement and the Church of Euthanasia are well-known examples of social movements in favor of antinatalism and human extinction.[169][2]

Antinatalism is commonly endorsed by misanthropic thinkers[42] but there are also many other ways that could lead to the extinction of the human species. This field is still relatively speculative but various suggestions have been made about threats to the long-term survival of the human species, like nuclear wars, self-replicating nanorobots, or super-pathogens.[170][171][172] Such cases are usually seen as terrible scenarios and dangerous threats but misanthropes may instead interpret them as reasons for hope because the abhorrent age of humanity in history may soon come to an end.[173] A similar sentiment is expressed by Bertrand Russell. He states in relation to the existence of human life on earth and its misdeeds that they are "a passing nightmare; in time the earth will become again incapable of supporting life, and peace will return."[174]

Human exceptionalism and deep ecology

Human exceptionalism is the claim that human beings have unique importance and are exceptional compared to all other species. It is often based on the claim that they stand out because of their special capacities, like intelligence, rationality, and autonomy.[175] In religious contexts, it is frequently explained in relation to a unique role that God foresaw for them or that they were created in God's image.[176] Human exceptionalism is usually combined with the claim that human well-being matters more than the well-being of other species. This line of thought can be used to draw various ethical conclusions. One is the claim that humans have the right to rule the planet and impose their will on other species. Another is that inflicting harm on other species may be morally acceptable if it is done with the purpose of promoting human well-being and excellence.[175][177]

Generally speaking, the position of human exceptionalism is at odds with misanthropy in relation to the value of humanity.[177] But this is not necessarily the case and it may be possible to hold both positions at the same time. One way to do this is to claim that humanity is exceptional because of a few rare individuals but that the average person is bad.[178] Another approach is to hold that human beings are exceptional in a negative sense: given their destructive and harmful history, they are much worse than any other species.[177]

Theorists in the field of deep ecology are also often critical of human exceptionalism and tend to favor a misanthropic perspective.[179][180] Deep ecology is a philosophical and social movement that stresses the inherent value of nature and advocates a radical change in human behavior toward nature.[181] Various theorists have criticized deep ecology based on the claim that it is misanthropic by privileging other species over humans.[180] For example, the deep ecology movement Earth First! has faced severe criticism when they praised the AIDS epidemic in Africa as a solution to the problem of human overpopulation in their newsletter.[182][183]

See also

- Asociality – lack of motivation to engage in social interaction

- Antisocial – disregard for, and violation of, the rights of others

- Antihumanism – rejection of humanism

- Cattle Decapitation

- Cosmicism

- Emotional isolation

- Hatred (video game)

- Machiavellianism (psychology)

- Nihilism

- Social alienation

References

Citations

- Benatar 2015, pp. 34–64.

- MacCormack 2020, p. 143.

- Merriam-Webster staff 2023.

- AHD staff 2022a.

- OED staff 2019.

- Harper 2019.

- Kidd 2020b.

- Cooper 2018, p. 7.

- Edyvane 2013, pp. 53–65.

- AHD staff 2022.

- Lim 2006, p. 167.

- Sawaya 2014, p. 207.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 6–7.

- Cooper 2018, pp. 54–6.

- Benatar 2015, pp. 38, 41.

- Gibson 2017, p. 190.

- Gilmore 2010, p. 12.

- Gibson 2017, p. 145.

- Harris 2022, p. 118.

- Kidd 2020, pp. 66–72.

- Kidd 2023.

- Cooper 2018, pp. 7, 13, 54–8.

- Kidd 2022, pp. 75–99, 4. Misanthropy and the Hatred of Humanity.

- Tsakalakis 2020, p. 144.

- Harris 2022, p. 21.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 6–9.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 6, 9, 29.

- Querido 2020, pp. 152–7.

- Wilford & Stoner 2021, pp. 42–3.

- Svoboda 2022, p. 8.

- Harris 2022, p. 22.

- Harris 2022, pp. 20–22.

- King 1993, pp. 57–8.

- Babbitt 2015, Chapter VII: Romantic Irony.

- Svoboda 2022, p. 7.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 7–8.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 8–9.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 8–9, 40.

- Cooper 2018, pp. 110–1.

- Cooper 2018, pp. 115–6.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 14, 115.

- Svoboda 2022, p. 14.

- Cooper 2018, pp. 118–9.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 117–8.

- Cooper 2018, pp. 7, 47–8.

- Cooper 2018, pp. 3, 8, 48.

- Benatar 2015, pp. 39–42.

- Benatar 2015, pp. 34–36, 55.

- Cooper 2018, pp. 7, 13, 48.

- Hurka 2020, Virtues and vices.

- Hurka 2001, pp. 195–212.

- Benatar 2015, pp. 39–48.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 4–5.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 3, 5.

- Madison 2017, pp. 1–6.

- Litvak & Lerner 2009, pp. 89–90, cognitive bias.

- Cooper 2018, pp. 50–51.

- Svoboda 2022, p. 18.

- Hackforth 1946, pp. 118–.

- Menon 2023.

- Benatar 2015, pp. 56–58.

- Cooper 2018, pp. 7, 48.

- Harris 2022, p. 195.

- Chambers 1847, p. 191.

- Shakespeare 2001, p. 208.

- White 1989, p. 134.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 98–9, 107–8.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 13, 119, 207.

- Gibson 2017, p. 119.

- Hooghe & Stolle 2003, p. 185.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 13, 62, 207.

- Tsakalakis 2020, p. 142.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 61, 207.

- Smith 1997, pp. 170–196.

- Rosenberg 1956, pp. 690–695.

-

- Cooper 2018, pp. 4, 7, 54

- Benatar 2015, p. 55

- Querido 2020, pp. 152–7

- Gibson 2017, p. 13

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 3, 13.

- Benatar 2015, p. 55.

- Benatar 2015, pp. 37, 41–42.

- Benatar 2015, p. 43.

- Kidd 2020a, pp. 505–508.

- Cooper 2018, p. 80.

- Benatar 2015, pp. 38–9.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 1, 5.

- Benatar 2015, pp. 39–41.

- Benatar 2015, pp. 51–52.

- Gibson 2017, p. 64.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 13, 69.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 69–70.

- McGraw 2014, pp. 1–2, 1. Introduction.

- Shklar 1984, 5. Misanthropy (p. 192).

- Gibson 2017, pp. 4–5.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 4, 60.

- Harris 2022, pp. 202–2.

- Gibson 2017, p. 63.

- Gibson 2017, p. 65.

- Moyal 1989, pp. 131–148.

- Mark 2010.

- Ava 2004, p. 80.

- Stern 1993, p. 95.

- Yeroulanos 2016, p. 203.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 14–6.

- Arruzza & Nikulin 2016, p. 119.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 93, 95, 98.

- Williams 2023.

- Byrne 1997, p. 112.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 110–1.

- Cooper 2018, p. 19.

- King 1993, pp. 58–9.

- Gibson 2017, p. 112.

- Williams 2010, p. 147.

- Gibson 2017, p. 111.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 12, 15.

- Gibson 2017, p. 101.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 101–3.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 15–6.

- Troxell 2023.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 104–5.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 105–6.

- Cooper 2018, p. 2.

- Villa 2020, p. 127.

- Wilkerson 2023.

- Cooper 2018, p. 62.

- Solomon 2004, p. 67.

- Shaw 2021, p. xxxii.

- Grillaert 2008, p. 245.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 28–9.

- Kastenbaum 2003, Seven Deadly Sins.

- Hale & Thorson 2007, p. 46.

- Sarvis 2019, p. 8.

- Alger 1882, p. 109.

- Goodliff 2017, p. 108.

- Cooper 2018, p. 4.

- Cooper 2018, pp. 6–7.

- Morgan 2010, p. 91.

- Cooper 2018, p. 56.

- Catholic University of America 1967, Agape.

- Aung 1996, p. E12.

- Morgan 2010, p. 138.

- Harris 2022, pp. 27–30.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 1–2.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 2–4.

- Harris 2022, p. 58.

- Hawcroft 2007, p. 132.

- Gibson 2017, p. 14.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 84–5.

- Jan & Firdaus 2004, pp. 115.

- Moore 2011, p. 16.

- Pirson 2017, p. 58.

- Cornog 1998, p. 357.

- Steegmuller 1982, p. xiv.

- Raban 1992.

- Lee & Bird 2020, p. 164.

- Donohoo 2023.

- Bolus 2019, p. 24.

- Smith 2014, pp. 1–3, Introduction.

- Jenkins 2020, pp. 20–41.

- Fernández 2006, pp. 646–664.

- Cooper 2018, pp. 5–6.

- Gerber 2002, pp. 41–55.

- Metz 2012, pp. 1–9.

- Benatar 2015, pp. 34–35.

- Benatar 2015, pp. 55–56.

- Benatar 2015a.

- May 2018.

- Benatar 2015, pp. 39, 44, 48.

- Stibbe 2015, p. 13.

- Leslie 1998, pp. 25–26.

- Gordijn & Cutter 2013, p. 123.

- Svoboda 2022, p. 107.

- Svoboda 2022, pp. 107–108.

- Srinivasan & Kasturirangan 2016, pp. 126–227.

- Durst 2022, p. 1.

- Svoboda 2022, p. 9.

- Gibson 2017, pp. 64–65.

- Malone, Truong & Gray 2017.

- Sale 1988.

- Ball 2011.

- Hay 2002, p. 66.

- Taylor 2005.

Sources

- AHD staff (2022). "The American Heritage Dictionary entry: philanthropy". www.ahdictionary.com. HarperCollins.

- AHD staff (2022a). "The American Heritage Dictionary entry: misanthropy". www.ahdictionary.com. HarperCollins. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- Alger, W.R. (1882). The Solitudes of Nature and of Man; Or, The Loneliness of Human Life. Roberts. p. 109. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- Arruzza, Cinzia; Nikulin, Dmitri (21 November 2016). Philosophy and Political Power in Antiquity. Brill. p. 119. ISBN 9789004324626.

- Aung, SK (April 1996). "Loving kindness: the essential Buddhist contribution to primary care". Humane Health Care International. 12 (2): E12. PMID 14986605.

- Ava, Chitwood (2004). Death by philosophy : the biographical tradition in the life and death of the archaic philosophers Empedocles, Heraclitus, and Democritus. University of Michigan Press. p. 80. ISBN 0472113887. OCLC 54988783.

- Babbitt, Irving (2015). "Chapter VII: Romantic Irony". Rousseau and Romanticism. Project Gutenberg.

- Ball, Terence (2011). Blanchfield, Deirdre S. (ed.). Environmental Encyclopedia. Gale / Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1414487366.

- Benatar, David (2015). "The Misanthropic Argument for Anti-natalism". In S. Hannan; S. Brennan; R. Vernon (eds.). Permissible Progeny?: The Morality of Procreation and Parenting. Oxford University Press. pp. 34–64. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199378111.003.0002. ISBN 9780199378142.

- Benatar, David (15 July 2015a). "'We Are Creatures That Should Not Exist': The Theory Of Anti-Natalism". The Critique. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- Bolus, Michael Peter (26 August 2019). Aesthetics and the Cinematic Narrative: An Introduction. Anthem Press. p. 24. ISBN 9781783089826.

- Bostrom, Nick (2003). "Extinction, Human". In Demeny, Paul George; McNicoll, Geoffrey (eds.). Encyclopedia of Population. Macmillan Reference. ISBN 978-0028656779.

- Brown, Alan S.; Logan, Chris (22 June 2009). The Psychology of the Simpsons: D'oh!. BenBella Books, Inc. p. 229. ISBN 9781935251392.

- Byrne, James M. (1 January 1997). Religion and the Enlightenment: From Descartes to Kant. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 112. ISBN 9780664257606.

- Catholic University of America (1967). "Agape". New Catholic Encyclopedia. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780787639990.

- Chambers, Robert (1847). Essays moral and economic. W. & R. Chambers. p. 191.

- Cooper, David E. (2 February 2018). Animals and Misanthropy. Routledge. ISBN 9781351583770.

- Cornog, Mary W. (1998). Merriam-Webster's Vocabulary Builder. Merriam-Webster. p. 357. ISBN 9780877799108.

- Donohoo, Timothy (6 January 2023). "The Joker Has a Morbidly Hilarious Reason For Not Killing Red Hood". CBR.

- Durst, Dennis L. (2022). The Perils of Human Exceptionalism: Elements of a Nineteenth-Century Theological Anthropology. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 1. ISBN 9781666900194.

- Edyvane, Derek (2013). "Rejecting Society: Misanthropy, Friendship and Montaigne". Res Publica. 19 (1): 53–65. doi:10.1007/s11158-012-9206-2. S2CID 144666876.

- Fernández, Jordi (2006). "Schopenhauer's Pessimism". Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 73 (3): 646–664. doi:10.1111/j.1933-1592.2006.tb00552.x.

- Fink, Moritz (19 June 2019). The Simpsons: A Cultural History. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 82. ISBN 9781538116173.

- Gerber, Lisa (2002). "What is So Bad About Misanthropy?". Environmental Ethics. 24 (1): 41–55. doi:10.5840/enviroethics200224140.

- Gibson, Andrew (15 June 2017). Misanthropy: The Critique of Humanity. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781474293181.

- Gilmore, David D. (3 August 2010). Misogyny: The Male Malady. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780812200324.

- Goertz, Allie; Prescott, Julia; Oakley, Bill; Weinstein, Josh (18 September 2018). 100 Things The Simpsons Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die (in Arabic). Triumph Books. p. 72. ISBN 9781641251099.

- Goodliff, P.W. (2017). Shaped for Service: Ministerial Formation and Virtue Ethics. Lutterworth Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7188-4736-4. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- Gordijn, Bert; Cutter, Anthony Mark (2013). In Pursuit of Nanoethics. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 123. ISBN 978-1402068171.

- Grillaert, Nel (2008). What the God-seekers Found in Nietzsche: The Reception of Neitzche's Übermensch by the Philosophers of the Russian Religious Renaissance. Rodopi. p. 245. ISBN 9789042024809.

- Hackforth, R. (1946). "Moral Evil and Ignorance in Plato's Ethics". Classical Quarterly. 40 (3–4): 118–. doi:10.1017/S0009838800023442. S2CID 145412342.

- Hale, Tom; Thorson, Stephen (2007). The Applied Old Testament Commentary. David C Cook. p. 46. ISBN 9780781448642.

- Harper, Douglas (2019). "misanthropy". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- Harris, Joseph (November 2022). Misanthropy in the Age of Reason. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192867575.

- Hawcroft, Michael (27 September 2007). Molière: Reasoning With Fools. Oxford University Press. p. 132. ISBN 9780191527937.

- Hay, P. R. (2002). Main currents in western environmental thought. Indiana University Press. p. 66. ISBN 0253340535.

- Hooghe, M.; Stolle, D. (15 May 2003). Generating Social Capital: Civil Society and Institutions in Comparative Perspective. Springer. p. 185. ISBN 9781403979544.

- Hurka, Thomas (2020). "Virtues and vices". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge.

- Hurka, Thomas (2001). "Vices as Higher-Level Evils". Utilitas. 13 (2): 195–212. doi:10.1017/s0953820800003137. S2CID 145225191.

- Jan, K. M.; Firdaus, Shabnam (2004). Perspectives on Gulliver's Travels. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 115. ISBN 9788126903450.

- Jenkins, Scott (2020). "The Pessimistic Origin of Nietzsche's Thought of Eternal Recurrence". Inquiry: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy. 63 (1): 20–41. doi:10.1080/0020174x.2019.1669976. S2CID 211969776.

- Kastenbaum, Robert (2003). "Seven Deadly Sins". Encyclopedia of Death and Dying. Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 9780028656908.

- Kidd, Ian James (28 February 2023). "From Vices to Corruption to Misanthropy". TheoLogica. 7 (2). doi:10.14428/thl.v7i2.66863. S2CID 257266338.

- Kidd, Ian James (2022). "4. Misanthropy and the Hatred of Humanity". In Birondo, Noell (ed.). The Moral Psychology of Hate. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 75–99. ISBN 978-1538160862.

- Kidd, Ian James (1 April 2020). "Animals, Misanthropy, and Humanity". Journal of Animal Ethics. 10 (1): 66–72. doi:10.5406/janimalethics.10.1.0066. S2CID 219093758.

- Kidd, Ian James (2020a). "Humankind, Human Nature, and Misanthropy". Metascience. 29 (3): 505–508. doi:10.1007/s11016-020-00562-8. S2CID 225274682.

- Kidd, Ian James (2020b). "Philosophical Misanthropy". philosophynow.org (139).

- King, Florence (15 March 1993). With Charity Toward None: A Fond Look At Misanthropy. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312094140.

- Lee, Judith Yaross; Bird, John (16 November 2020). Seeing MAD: Essays on MAD Magazine's Humor and Legacy. University of Missouri Press. p. 164. ISBN 9780826274489.

- Leslie, John (1998). The end of the world: the science and ethics of human extinction. Routledge. pp. 25–26. ISBN 0203007727.

- Lim, Song Hwee (31 August 2006). Celluloid Comrades: Representations of Male Homosexuality in Contemporary Chinese Cinemas. University of Hawaii Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780824830779.

- Litvak, P.; Lerner, J. S. (2009). "cognitive bias". In Sander, David; Scherer, Klaus (eds.). The Oxford companion to emotion and the affective sciences. Oxford University Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-0198569633.

- MacCormack, Patricia (2020). The Ahuman Manifesto: Activism for the End of the Anthropocene. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 143. ISBN 978-1350081093.

- Madison, B. J. C. (2017). "On the Nature of Intellectual Vice". Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective. 6 (12): 1–6.

- Mahathera, Nyanatiloka (1964). "II. Kamma and Rebirth". Karma and Rebirth. Buddhist Publication Society.

- Malone, Karen; Truong, Son; Gray, Tonia (2017). Reimagining Sustainability in Precarious Times. Springer. ISBN 978-9811025501.

- Mark, Joshua J. (2010-07-14). "Heraclitus of Ephesus". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- May, Todd (December 17, 2018). "Would Human Extinction Be a Tragedy?". The New York Times.

Human beings are destroying large parts of the inhabitable earth and causing unimaginable suffering to many of the animals that inhabit it. This is happening through at least three means. First, human contribution to climate change is devastating ecosystems .... Second, the increasing human population is encroaching on ecosystems that would otherwise be intact. Third, factory farming fosters the creation of millions upon millions of animals for whom it offers nothing but suffering and misery before slaughtering them in often barbaric ways. There is no reason to think that those practices are going to diminish any time soon. Quite the opposite.

- McGraw, Shannon (2014). "1. Introduction". Misanthropy and Criminal Behavior (PDF). pp. 1–2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-07-09.

- Menon, Sangeetha (2023). "Vedanta, Advaita". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- Merriam-Webster staff (2023). "Definition of Misanthropy". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- Metz, Thaddeus (2012). "Contemporary Anti-Natalism, Featuring Benatar's Better Never to Have Been". South African Journal of Philosophy. 31 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1080/02580136.2012.10751763. S2CID 143091736.

- Moore, Grace (2011). A Christmas Carol: Insight Text Guides. Insight Publications. p. 16. ISBN 9781921411915.

- Morgan, Diane (2010). Essential Buddhism: A Comprehensive Guide to Belief and Practice. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313384523.

- Moyal, Georges J.D. (1989). "On Heraclitus's Misanthropy". Revue de Philosophie Ancienne. 7 (2): 131–148. ISSN 0771-5420. JSTOR 24353851.

- Navia, Luis E. (1996). Classical Cynicism: A Critical Study. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313300158.

- OED staff (2019). "misanthropy". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- Pirson, Michael (14 September 2017). Humanistic Management: Protecting Dignity and Promoting Well-Being. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 9781107160729.

- Querido, Pedro (February 2020). "Andrew Gibson, Misanthropy: The Critique of Humanity". Comparative Critical Studies. 17 (1): 152–7. doi:10.3366/ccs.2020.0349. hdl:10451/46707. ISSN 1744-1854. S2CID 216373633.

- Raban, Jonathan (October 17, 1992). "Books: Mr Miseryguts: Philip Larkin's letters show all the grim humor that was a hallmark of his great poems, but, as the years pass, they also chart the true depths of his misanthropy and despair". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2022-05-15. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- Rosenberg, Morris (December 1956). "Misanthropy and Political Ideology". American Sociological Review. 21 (6): 690–695. doi:10.2307/2088419. JSTOR 2088419.

- Sale, Kirkpatrick (14 May 1988). "Deep Ecology And Its Critics" (PDF). The Nation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-06.

- Sarvis, W. (2019). Embracing Philanthropic Environmentalism: The Grand Responsibility of Stewardship. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-4766-7736-1. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- Sawaya, Francesca (15 July 2014). The Difficult Art of Giving: Patronage, Philanthropy, and the American Literary Market. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 207. ISBN 9780812290035.

- Shakespeare, William (3 April 2001). Timon of Athens. Cambridge University Press. p. 208. ISBN 9781139835114.

- Shaw, George Bernard (2021). Man and Superman, John Bull's Other Island, and Major Barbara. Oxford University Press. p. xxxii. ISBN 9780198828853.

- Shklar, Judith N. (1984). "5. Misanthropy". Ordinary Vices. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0674641754.

- Smith, Cameron (2014). "Introduction". Philosophical Pessimism: A Study In The Philosophy Of Arthur Schopenhauer. pp. 1–3.

- Smith, Tom W. (June 1997). "Factors Relating to Misanthropy in Contemporary American Society". Social Science Research. 26 (2): 170–196. doi:10.1006/ssre.1997.0592.

- Solomon, Robert C. (26 August 2004). In Defense of Sentimentality. Oxford University Press. p. 67. ISBN 9780198033288.

- Srinivasan, Krithika; Kasturirangan, Rajesh (October 2016). "Political ecology, development, and human exceptionalism". Geoforum. 75: 126–227. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.07.011. hdl:20.500.11820/92518b23-6ace-42ed-852a-1cf93f65a898. S2CID 148390374.

- Steegmuller, Francis, ed. (1982). The Letters of Gustave Flaubert: 1857-1880. Harvard University Press. p. xiv. ISBN 0674526406.

- Stern, Paul (1993). Socratic Rationalism and Political Philosophy: An Interpretation of Plato's Phaedo. SUNY Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780791415733.

- Stibbe, Arran (2015). Ecolinguistics: Language, Ecology and the Stories We Live By. Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 978-1317511908.

- Stohr, Karen E. (2002). "Virtue Ethics and Kant's Cold-Hearted Benefactor". The Journal of Value Inquiry. 36 (2/3): 187–204. doi:10.1023/A:1016192117676. S2CID 169393221.

- Svoboda, Toby (29 April 2022). A Philosophical Defense of Misanthropy. Taylor & Francis Limited. ISBN 9781032029986.

- Taylor, Bron (2005). Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Macmillan Reference. ISBN 978-0028657349.

- Troxell, Mary (2023). "Schopenhauer, Arthur". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- Tsakalakis, Thomas (15 October 2020). Political Correctness: A Sociocultural Black Hole. Routledge. ISBN 9781000205084.

- Villa, Dana (1 September 2020). Socratic Citizenship. Princeton University Press. p. 127. ISBN 9780691218175.

- White, David A. (1989). Myth and Metaphysics in Plato's Phaedo. Susquehanna University Press. p. 134. ISBN 9780945636014.

- Wilford, Paul T.; Stoner, Samuel A. (4 June 2021). Kant and the Possibility of Progress: From Modern Hopes to Postmodern Anxieties. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 42–3. ISBN 9780812297799.

- Wilkerson, Dale (2023). "Nietzsche, Friedrich: 1. Life". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- Williams, David Lay (1 November 2010). Rousseau's Platonic Enlightenment. Penn State Press. p. 147. ISBN 9780271045511.

- Williams, Garrath (2023). "Hobbes, Thomas: Moral and Political Philosophy". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- Wolfman, Greg (25 August 2023). Masculinities in the US Hangout Sitcom. Taylor & Francis. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-000-90274-7.

- Yeroulanos, Marinos (30 June 2016). A Dictionary of Classical Greek Quotations. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 203. ISBN 9781786730497.

External links

Media related to Misanthropy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Misanthropy at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of misanthropy at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of misanthropy at Wiktionary Quotations related to Misanthropy at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Misanthropy at Wikiquote