Kenji Miyazawa

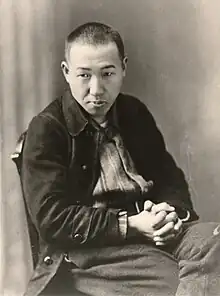

Kenji Miyazawa (宮沢 賢治 or 宮澤 賢治, Miyazawa Kenji, 27 August 1896 – 21 September 1933) was a Japanese novelist and poet of children's literature from Hanamaki, Iwate, in the late Taishō and early Shōwa periods. He was also known as an agricultural science teacher, a vegetarian, cellist, devout Buddhist, and utopian social activist.[1]

Kenji Miyazawa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kenji Miyazawa | |||||

| Native name | 宮沢 賢治 | ||||

| Born | August 27, 1896 Hanamaki, Iwate, Japan | ||||

| Died | September 21, 1933 (aged 37) Hanamaki, Iwate, Japan | ||||

| Occupation | Writer, poet, teacher, geologist | ||||

| Nationality | Japanese | ||||

| Period | Taishō and early Shōwa periods | ||||

| Genre | Children's literature, poetry | ||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Hiragana | みやざわ けんじ | ||||

| Katakana | ミヤザワ ケンジ | ||||

| Kyūjitai | 宮澤 賢治 | ||||

| Shinjitai | 宮沢 賢治 | ||||

| |||||

Some of his major works include Night on the Galactic Railroad, Kaze no Matasaburō, Gauche the Cellist, and The Night of Taneyamagahara. Miyazawa converted to Nichiren Buddhism after reading the Lotus Sutra, and joined the Kokuchūkai, a Nichiren Buddhist organization. His religious and social beliefs created a rift between him and his wealthy family, especially his father, though after his death his family eventually followed him in converting to Nichiren Buddhism. Miyazawa founded the Rasu Farmers Association to improve the lives of peasants in Iwate Prefecture. He was also interested in Esperanto and translated some of his poems into that language.[2]

He died of pneumonia in 1933. Almost totally unknown as a poet in his lifetime, Miyazawa's work gained its reputation posthumously,[3] and enjoyed a boom by the mid-1990s on his centenary.[4] A museum dedicated to his life and works was opened in 1982 in his hometown. Many of his children's stories have been adapted as anime, most notably Night on the Galactic Railroad. Many of his tanka and free verse poetry, translated into many languages, are still popular today.

Biography

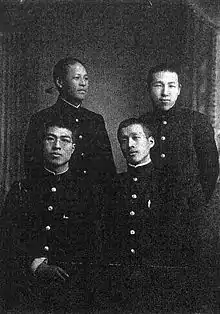

Miyazawa was born in the town of Hanamaki,[5] Iwate, the eldest son[6] of a wealthy pawnbroking couple, Masajirō and his wife Ichi.[5][7][8] The family were also pious followers of the Pure Land Sect, as were generally the farmers in that district.[9] His father, from 1898 onwards, organized regular meetings in the district where monks and Buddhist thinkers gave lectures and Miyazawa, together with his younger sister, took part in these meetings from an early age.[7] The area was an impoverished rice-growing region, and he grew to be troubled by his family's interest in money-making and social status.[4] Miyazawa was a keen student of natural history from an early age, and also developed an interest as a teenager in poetry, coming under the influence of a local poet, Takuboku Ishikawa.[4] After graduating from middle school, he helped out in his father's pawnshop.[10] By 1918, he was writing in the tanka genre, and had already composed two tales for children.[4] At high school he converted to the Hokke sect after reading the Lotus Sutra, a move which was to bring him into conflict with his father.[4] In 1918, he graduated from Morioka Agriculture and Forestry College (盛岡高等農林学校, Morioka Kōtō Nōrin Gakkō, now the Faculty of Agriculture at Iwate University).[11] He embraced vegetarianism in the same year.[4] A bright student, he was then given a position as a special research student in geology, developing an interest in soil science and in fertilizers.[4] Later in 1918, he and his mother went to Tokyo to look after his younger sister Toshi (宮澤トシ, Miyazawa Toshi), who had fallen ill while studying in Japan Women's University[6][8] He returned home after his sister had recovered early the following year.[4][12]

As a result of differences with his father over religion, his repugnance for commerce, and the family pawnshop business in particular (he yielded his inheritance to his younger brother Seiroku),[4] he left Hanamaki for Tokyo in January 1921.[4][5] There, he joined Tanaka Chigaku's Kokuchūkai, and spent several months in dire poverty preaching Nichiren Buddhism in the streets.[4] After eight months in Tokyo, he took once more to writing children's stories, this time prolifically, under the influence of another Nichiren priest, Takachiyo Chiyō, who dissuaded him from the priesthood by convincing him that Nichiren believers best served their faith by striving to embody it in their profession.[4] He returned to Hanamaki due to the renewed illness of his beloved younger sister.[5][13] At this time he became a teacher at the Agricultural School in Hanamaki.[13] On November 27, 1922, Toshi finally succumbed to her illness and died at age 24.[6] This was a traumatic shock for Miyazawa, from which he never recovered.[13] He composed three poems on the day of her death, collectively entitled "Voiceless Lament" (無声慟哭, Musei Dōkoku).[4][14][lower-alpha 1]

He found employment as a teacher in agricultural science at Hanamaki Agricultural High School (花巻農学校).[4] He managed to put out a collection of poetry, Haru to Shura (春と修羅, "Spring and the Demon") in April 1924, thanks to some borrowings and a major subvention from a producer of nattō.[15] His collection of children's stories and fairy tales, Chūmon no Ōi Ryōriten (注文の多い料理店, "The Restaurant of Many Orders"), also self-published, came out in December of the same year.[4][5] Although neither were commercial successes — they were largely ignored — his work did come to the attention of the poets Kōtarō Takamura and Shinpei Kusano, who admired his writing greatly and introduced it to the literary world.[5]

As a teacher, his students viewed him as passionate but rather eccentric, as he insisted that learning came through actual, firsthand experience of things. He often took his students out of the classroom, not only for training, but just for enjoyable walks in the hills and fields. He also had them put on plays they wrote themselves.

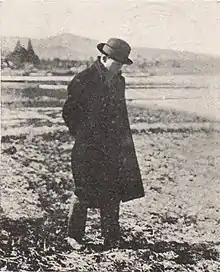

Kenji resigned his post as a teacher in 1926 to become a farmer and help improve the lot of the other farmers in the impoverished north-eastern region of Japan by sharing his theoretical knowledge of agricultural science,[5][16] by imparting to them improved, modern techniques of cultivation. He also taught his fellow farmers more general topics of cultural value, such as music, poetry, and whatever else he thought might improve their lives.[5][16] He introduced them to classical music by playing to audiences compositions from Beethoven, Schubert, Wagner and Debussy on his gramophone.[9] In August 1926 he established the Rasuchijin Society (羅須地人協会, Rasuchijin Kyōkai, also called the "Rasu Farmers Association").[4] When asked what "Rasuchijin" meant, he said it meant nothing in particular, but he was probably thinking of chi (地, "earth") and jin (人, "man").[16] He introduced new agricultural techniques and more resistant strains of rice.[17] At the detached house of his family, where he was staying at the time, he gathered a group of youths from nearby farming families and lectured on agronomy. The Rasuchijin Society also engaged in literary readings, plays, music and other cultural activities.[4] It was disbanded after two years as Japan was being swept up by a militarist turn, in 1928, when the authorities closed it down.[4][16]

Not all of the local farmers were grateful for his efforts, with some sneering at the idea of a city-slicker playing farmer, and others expressing disappointment that the fertilizers Kenji introduced were not having the desired effects.[18] He advocated natural fertilizers, while many preferred a Western chemical 'fix', which, when it failed, did not stop many from blaming Kenji.[9] Their reservations may have also persisted as he had not wholly broken from economic dependence on his father, to whom farmers were often indebted when their crops failed, in addition to his defection to the Lotus Sect soured their view, as farmers in his area were, like his own father, adherents of the Pure Land Sect.[9] Kenji in turn did not hold an ideal view of the farmers; in one of his poems he describes how a farmer bluntly tells him that all his efforts have done no good for anyone.[19]

According to Sibayama Zyun'iti, he started learning Esperanto in 1926, but never reached a high level in the language.[20][21] He also studied English and German. At some point he translated some of his poems into Esperanto;[2] the translated pieces were published in 1953, long after his death.[20] According to Jouko Lindstedt, Kenji was made interested in Esperanto by the Finnish scientist and Esperantist Gustaf John Ramstedt, who was working as a diplomat for Finland in Japan.[22]

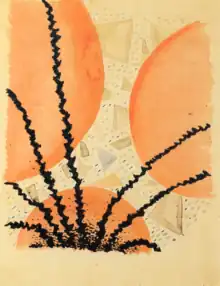

Kenjis writings from this period show sensitivity for the land and for the people who work in it. A prolific writer of children's stories, many that appear superficially to be light or humorous, all contain stories intended for moral education of the reader. He wrote some works in prose and some stage plays for his students and left behind a large amount of tanka and free verse, most of which was discovered and published posthumously. His poetry, which has been translated into numerous languages, has a considerable following to this day. A number of his children's works have been made into animated movies, anime, in Japan.

He showed little interest in romantic love or sex, both in his private life and in his literary work.[23] Kenji's close friend Tokuya Seki (関登久也, Seki Tokuya) wrote that he died a virgin.[24]

Illness and death

Kenji fell ill in summer 1928, and by the end of that year this had developed into acute pneumonia.[25] He once wept on learning that he had been tricked into eating carp liver.[26] He struggled with pleurisy for many years and was often incapacitated for months at a time. His health improved nonetheless sufficiently for him to take on consultancy work with a rock-crushing company in 1931.[4] The respite was brief; by September of that year, on a visit to Tokyo, he caught pneumonia and had to return to his hometown.[4] In the autumn of 1933, his health seemed to have improved enough for him to watch a local Shinto procession from his doorway; a group of local farmers approached him and engaged him in conversation about fertilizer for about an hour.[27] He died the following day, having been exhausted by the length of his discussion with the farmers.[27] On his deathbed he asked his father to print 1,000 copies of the Lotus Sutra for distribution. His family initially had him buried in the family temple Anjōji (安浄寺), but when they converted to Nichiren Buddhism in 1951, he was moved to the Nichiren temple Shinshōji (身照寺).[28] After his death, he became known in his district as Kenji-bosatsu (賢治菩薩).[4]

Miyazawa left his manuscripts to his younger brother Seiroku, who kept them through the air raids in WWII and eventually got them published.[29]

Early writings

Kenji started writing poetry as a schoolboy, and composed over a thousand tanka[8] beginning at roughly age 15,[6] in January 1911, a few weeks after the publication of Takuboku's "A Handful of Sand".[30] He favoured this form until the age of 24. Keene said of these early poems that they "were crude in execution, [but] they already prefigure the fantasy and intensity of emotion that would later be revealed in his mature work".[8]

Kenji was removed physically from the poetry circles of his day.[31] He was an avid reader of modern Japanese poets such as Hakushū Kitahara and Sakutarō Hagiwara, and their influence can be traced on his poetry, but his life among farmers has been said to have influenced his poetry more than these literary interests.[32] When he first started writing modern poetry, he was influenced by Kitahara, as well as his fellow Iwatean Takuboku Ishikawa[8]

Kenji's works were influenced by contemporary trends of romanticism and the proletarian literature movement. His readings in Buddhist literature, particularly the Lotus Sutra, to which he became devoted, also came to have a strong influence on his writings.

In 1919, his sister prepared a collection of 662 of his tanka for publication.[13] Kenji edited a volume of extracts from Nichiren’s writings, the year before he join the Kokuchūkai (see below).[13]

He largely abandoned tanka by 1921, and turned his hand instead to the composition of free verse, involving an extension of the conventions governing tanka verse forms.[33] He is said also to have written three thousand pages a month worth of children's stories during this period,[13] thanks to the advice of a priest in the Nichiren order, Takachiyo Chiyō.[4] At the end of the year he managed to sell one of these stories for five yen, which was the only payment he received for his writings during his own lifetime.[13]

Later poetry

The "charms of Kenji's poetry", critic Makota Ueda writes, include "his high idealism, his intensely ethical life, his unique cosmic vision, his agrarianism, his religious faith, and his rich and colorful vocabulary." Ultimately, Ueda writes, "they are all based in a dedicated effort to unify the heterogeneous elements of modern life into a single, coherent whole."[34]

It was in 1922 that Kenji began composing the poetry that would make up his first collection, Haru to Shura.[13] The day his sister died, November 27, 1922, he composed three long poems commemorating her, which Keene states to be among the best of his work.[13] Keene also remarks that the speed at which Kenji composed these poems was characteristic of the poet, as a few months prior he had composed three long poems, one more than 900 lines long, in three days.[35] The first of these poems on the death of his sister was Eiketsu no Asa (永訣の朝, "The Morning of Eternal Parting"), which was the longest.[36] Keene calls it the most affecting of the three.[36] It is written in the form of a "dialogue" between Kenji and Toshi (or Toshiko, as he often calls her[36]). Several lines uttered by his sister are written in a regional dialect so unlike Standard Japanese that Kenji provided translations at the end of the poem.[37] The poem lacks any kind of regular meter, but draws its appeal from the raw emotion it expresses; Keene suggests that Kenji learned this poetic technique from Sakutarō Hagiwara.[37]

Kenji could write a huge volume of poetry in a short time, based mostly on impulse, seemingly with no preconceived plan of how long the poem would be and without considering future revisions.[35]

Donald Keene has speculated that his love of music affected the poetry he was writing in 1922, as this was when he started collecting records of western music, particularly Bach and Beethoven.[13] Much of his poetic tone derives from synesthesia involving music becoming color, especially after the period 1921 and 1926 when he started listening to music of Debussy, Wagner and Strauss.[5]

He was associated with the poetry magazine Rekitei (歴程).[38][39]

Only the first part in four of Haru to Shura was published during Kenji's lifetime.[27] It appeared in an edition of one thousand copies, but only one hundred sold.[27] For most of his literary career his poems saw publication only in local papers and magazines, but by the time of his death major literary publications had been made aware of him; he died just as his fame was beginning to spread.[27]

With the exception of a few poems in classical Japanese written near the end of his life, virtually all Myazawa'a modern poetry was in colloquial Japanese, occasionally even in dialect.[8] The poems included in Haru to Shura include a liberal sprinkling of scientific vocabulary, Sanskrit phrases, Sino-Japanese compounds and even some Esperanto words.[5] After starting out with traditional tanka, he developed a preference for long, free verse, but continued to occasionally compose tanka even as late as 1921.[8]

Kenji wrote his most famous poem, "Ame ni mo makezu", in his notebook on November 3, 1931.[40] Keene was dismissive of the poetic value of the poem, stating that it is "by no means one of Miyazawa's best poems" and that it is "ironic that [it] should be the one poem for which he is universally known", but that the image of a sickly and dying Kenji writing such a poem of resolute self-encouragement is striking.[40]

Later fiction

Kenji wrote rapidly and tirelessly.[5] He wrote a great number of children's stories, many of them intended to assist in moral education.[5]

His best-known stories include Night on the Galactic Railroad (銀河鉄道の夜, Ginga Tetsudō no Yoru), The Life of Guskō Budori (グスコーブドリの伝記, Gusukō Budori no Denki), Matasaburō of the Wind (風の又三郎, Kaze no Matasaburō), Gauche the Cellist (セロ弾きのゴーシュ, Sero Hiki no Gōshu), The Night of Taneyamagahara (種山ヶ原の夜, Taneyamagahara no Yoru), Vegetarian Great Festival (ビジテリアン大祭, Bijiterian Taisai), and The Dragon and the Poet (龍と詩人, Ryū to Shijin)

Other writings

In 1919, Kenji edited a volume of extracts from the writings of Nichiren,[13] and in December 1925[41] a solicitation to build a Nichiren temple (法華堂建立勧進文, Hokke-dō konryū kanjin-bun) in the Iwate Nippo under a pseudonym.[41]

He was also a frequent letter-writer.

Religious beliefs

Kenji was born into a family of Pure Land Buddhists, but in 1915 converted to Nichiren Buddhism upon reading the Lotus Sutra and being captivated by it.[8] His conversion created a rift with his relatives, but he nevertheless became active in trying to spread the faith of the Lotus Sutra, walking the streets crying Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō.[13] In January 1921 he made several unsuccessful attempts to convert his family to Nichiren Buddhism.[13]

From January to September 1921, he lived in Tokyo working as a street proselytizer for the Kokuchūkai, a Buddhist-nationalist organization[42] that had initially turned down his service.[13] The general consensus among modern Kenji scholars is that he became estranged from the group and rejected their nationalist agenda,[43] but a few scholars such as Akira Ueda, Gerald Iguchi and Jon Holt argue otherwise.[44] The Kokuchūkai's official website continues to claim him as a member, also claiming that the influence of Nichirenism (the group's religio-political philosophy) can be seen in Kenji's later works such as Ame ni mo Makezu, while acknowledging that others have expressed the view that Kenji became estranged from the group after returning to Hanamaki.[45]

Kenji remained a devotee of the Lotus Sutra until his death, and continued attempting to convert those around him. He made a deathbed request to his father to print one thousand copies of the sutra in Japanese translation and distribute them to friends and associates.[8][27]

Kenji incorporated a relatively large amount of Buddhist vocabulary in his poems and children's stories.[8] He drew inspiration from mystic visions in which he saw the bodhisattva Kannon, the Buddha himself and fierce demons.[5]

In 1925 Kenji pseudonymously published a solicitation to build a Nichiren temple (法華堂建立勧進文, Hokke-dō konryū kanjin-bun) in Hanamaki,[28][41][46] which led to the construction of the present Shinshōji,[28] but on his death his family, who were followers of Pure Land Buddhism, had him interred at a Pure Land temple.[46] His family converted to Nichiren Buddhism in 1951[28][46] and moved his grave to Shinshōji,[46] where it is located today.[28][46][47][48]

Donald Keene suggests that while explicitly Buddhist themes are rare in his writings, he incorporated a relatively large amount of Buddhist vocabulary in his poems and children's stories, and has been noted as taking a far greater interest in Buddhism than other Japanese poets of the twentieth century.[8] Keene also contrasted Kenji's piety to the "relative indifference to Buddhism" on the part of most modern Japanese poets.[8]

Themes

He loved his native province, and the mythical landscape of his fiction, known by the generic neologism, coined in a poem in 1923, as Īhatōbu (Ihatov) is often thought to allude to Iwate (Ihate in the older spelling). Several theories exist as to the possible derivations of this fantastic toponym: one theory breaks it down into a composite of I for 'Iwate'; hāto (English 'heart') and obu (English 'of'), yielding 'the heart or core of Iwate'. Others cite Esperanto and German forms as keys to the word's structure, and derive meanings varying from 'I don't know where' to 'Paradise'.[49] Among the variation of names, there is Ihatovo, and the addition of final o is supposed to be the noun ending of Esperanto, whose idea of common international language interested him.

Reception

Kenji's poetry managed to attract some attention during his lifetime. According to Hiroaki Sato, Haru to Shura, which appeared in April 1924, "electrified several of the poets who read it." These included the first reviewer, Dadaist Tsuji Jun, who wrote that he chose the book for his summer reading in the Japan Alps, and anarchist Shinpei Kusano (草野心平, Kusano Shinpei), who called the book shocking and inspirational, and Satō Sōnosuke, who wrote in a review for a poetry magazine that it "astonished [him] the most" out of all the books of poems he had received.[50] However, such occasional murmurs of interest were a far cry from the chorus of praise later directed toward his poetry.

In February 1934, some time after his memorial service, his literary friends held an event where they organized his unpublished manuscripts. These were slowly published over the following decade, and his fame increased rapidly in the postwar period.

The poet Gary Snyder is credited as introducing Kenji's poetry to English readers. "In the 1960s, Snyder, then living in Kyoto and pursuing Buddhism, was offered a grant to translate Japanese literature. He sought Burton Watson’s opinion, and Watson, a scholar of Chinese classics trained at the University of Kyoto, recommended Kenji." Some years earlier Jane Imamura at the Buddhist Study Center in Berkeley had shown him a Kenji translation which had impressed him.[51] Snyder's translations of eighteen poems by Kenji appeared in his collection, The Back Country (1967).[52]

The Miyazawa Kenji Museum was opened in 1982 in his native Hanamaki, in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of his death. It displays the few manuscripts and artifacts from Kenji's life that escaped the destruction of Hanamaki by American bombers in World War II.

In 1982, Oh! Production finished an animated feature film adaptation of Miyazawa's Gauche the Cellist,[53] with Studio Ghibli and Buena Vista Home Entertainment re-releasing the film as a double-disc commemoration of Miyazawa's 110th birthday along with an English-subtitle version.[54][55]

Manga artist Hiroshi Masumura has adapted many of Miyazawa's stories as manga since the 1980s, often using anthropomorphic cats as protagonists. The 1985 anime adaptation of Ginga tetsudō no yoru (Night on the Galactic Railroad), in which all signs in Giovanni and Campanella's world are written in Esperanto, is based on Masumura's manga. In 1996, to mark the 100th anniversary of Kenji's birth, the anime Īhatōbu Gensō: Kenji no Haru (Ihatov Fantasy: Kenji's Spring; North American title: Spring and Chaos) was released as a depiction of Kenji's life.[56] As in the Night on the Galactic Railroad anime, the main characters are depicted as cats.

The Japanese culture and lifestyle television show Begin Japanology aired on NHK World featured a full episode on Miyazawa Kenji in 2008.

The JR train SL Ginga (SL銀河, Esueru Ginga) was restored with inspiration from and named in honor of his work in 2013.[57]

The 2015 anime Punch Line and its video game adaptation features a self-styled hero who calls himself Kenji Miyazawa and has a habit of quoting his poetry when arriving on scene. When other characters wonder who he is after his sudden initial appearance, they point out that he cannot be the "poet who wrote books for kids" because he died in 1933.[58]

See also

- The Nighthawk Star

- Scenic areas of Ihatov

- Category:Works by Kenji Miyazawa

Notes

- The individual poems are entitled "Eiketsu no Asa" (永訣の朝), "Matsu no Hari" (松の針) and "Musei Dōkoku" (無声慟哭).[14]

Reference list

- Curley, Melissa Anne-Marie, "Fruit, Fossils, Footprints: Cathecting Utopia in the Work of Miyazawa Kenji", in Daniel Boscaljon (ed.), Hope and the Longing for Utopia: Futures and Illusions in Theology and Narrative, James Clarke & Co./ /Lutterworth Press 2015. pp.96–118, p.96.

- David Poulson, Miyazawa Kenji

- Makoto Ueda, Modern Japanese Poets and the Nature of Literature, Stanford University Press, 1983 pp.184–320, p.184

- Kilpatrick 2014, pp. 11–25.

- Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan article "Miyazawa Kenji" (p. 222–223). 1983. Tokyo: Kodansha.

- "Ryakenpu, Omona Dekigoto". Miyazawa Kenji Memorial Society website. Miyazawa Kenji Memorial Society. Archived from the original on April 29, 2015. Retrieved May 1, 2015..

- Massimo Cimarelli (ed.tr.), Miyazawa Kenji: Il drago e il poeta, Volume Edizioni srl, 2014 p.3

- Keene 1999, p. 284.

- Margaret Mitsutani, "The Regional as the Center: The Poetry of Miyazawa Kenji", in Klaus Martens, Paul Duncan Morris, Arlette Warken (eds.) A World of Local Voices: Poetry in English Today, Königshausen & Neumann, 2003 pp.66–72 p.67.

- Ueda p.217

- Katsumi Fujii (March 23, 2009). Heisei Nijū-nendo Kokuritsu Daigaku Hōjin Iwate Daigaku Sotsugyōshiki Shikiji 平成20年度国立大学法人岩手大学卒業式式辞 [President’s Address at the Graduation Ceremony of Iwate University, School Year 2008] (Speech) (in Japanese). Morioka. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

1918年三月、本学農学部の前身である盛岡高等農林学校を卒業した賢治は、農業実践の指導を先ず教育の現場に求め、3年後に稗貫農学校(現在の花巻農業 高校)の教員となります。その後、詩に童話に旺盛な文芸活動を展開しましたが、病を得てさらに12年後、わずか37歳で帰らぬ人となったことは、ご承知の 通りです。

- Keene 1999, pp. 284–285.

- Keene 1999, p. 285.

- Miyakubo and Matsukawa 2013, p. 169.

- Hoyt Long ,On Uneven Ground: Miyazawa Kenji and the Making of Place in Modern Japan, Stanford University Press, 2011 p.369 n.5

- Keene 1999, p. 288.

- Mitsutani p.67.

- Keene 1999, p. 289.

- Keene 1999, p. 289, citing (note 197, p. 379) Miyazawa Kenji 1968, p. 311–314.

- Miyamoto Masao and Sibayama Zyun'iti: Poemoj de MIYAZAWA Kenzi, memtradukitaj esperanten

- "Kenji Miyazawa Ihatovkan Exhibition "Kenji Miyazawa and Esperanto Exhibition"".

- Jouko Lindstedt: Scientisto, diplomato, esperantisto (part 2)

- Pulvers 2007, pp. 9–28. "Kenji, it must be remembered, was a man who displayed no particular interest in romantic love or sex." Keene, though, states "he sometimes wandered all night in the wood in order in order to subdue the waves of sexual desire [he sensed within himself]" (Keene 1999, p. 288).

- Keene 1999, p. 288, citing (note 193, p. 379) Seki 1971, pp. 130–132.

- Keene 1999, pp. 289–290.

- Keene 1999, p. 290, citing (note 198, p. 379) Kushida, "Shijin to Shōzō" in Miyazawa Kenji 1968, p. 393.

- Keene 1999, p. 291.

- "Marugoto Jiten: Shinshōji". Ihatovo Hanamaki. Hanamaki Tourism & Convention Bureau. 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- Nagai, Kaori (2022). Foreeord in: "Night Train to the Starts and other stories" by Kenji Miyazawa. Vintage Classics. p. xii. ISBN 9781784877767.

- Ueda Makoto p.217.

- Keene 1999, p. 283.

- Keene 1999, pp. 283–284.

- Ueda pp.218–219

- Ueda 184

- Keene 1999, pp. 285–286.

- Keene 1999, p. 286.

- Keene 1999, p. 287.

- Keene 1999, p. 356 (also note 347, p. 384).

- Endō, Tomoyuki (October 10, 2012). "Nomura Kiwao-sensei ga "Fujimura Kinen Rekitei Shō" o jushō!". Wako University Blog. Wako University. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- Keene 1999, p. 290.

- Nabeshima (ed.) 2005, p. 34.

- Stone 2003, pp. 197–198.

- Stone 2003, p. 198.

- Holt, 2014, pp. 312–314.

- "Tanaka Chigaku-sensei no Eikyō o Uketa Hitobito: Miyazawa Kenji". Kokuchūkai official website. Kokuchūkai. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- Rasu Chijin Kyōkai. "Hanamaki o aruku". Chuo University faculty website. Chuo University. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

賢治は熱心な法華経信者でこの寺の建立のため「法華堂建立勧進文」まで書いているが、宮澤家が真宗だったため、死後真宗の寺に葬られていた。昭和二十六年、賢治の遺志を請けて、宮澤家が改宗し、日蓮宗のこの寺に葬られることになった。宮澤家の骨堂の左側にあるのが賢治供養塔である。

- "Minobu-betsuin Shinshōji". Tōhoku Jiin no Sōgō Jōhō Saito: E-Tera. Coyo Photo Office Corporation. 2010. Archived from the original on January 29, 2015. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- "Miyazawa Kenji: Yukari no Chi o Tazunete". Iwate Hanamaki Travel Agency website. Iwate Hanamaki Travel Agency. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- Kilpatrick p.192 n.77

- Sato (2007), 2.

- Sato (2007), 1.

- Snyder 1967, pp. 115–128.

- CINEMASIE.COM, Gauche the Cellist

- DVD talk, Cello Hiki no Gauche Archived 2006-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Ghibli World, 15th of July, Hayao Miyazaki's New Film Taneyamagahara no Yoru & Serohiki no Goshu Release Special Archived 2013-03-02 at the Wayback Machine

- "Ihatobu Genso: Kenji no Haru (TV Movie 1996)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- JR東:復元中のC58の列車名「SL銀河」に…来春運行 [JR East to name C58 train currently being restored "SL Ginga" - entering service next spring]. Mainichi.jp (in Japanese). Japan: The Mainichi Newspapers. 6 November 2013. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ""Fight, Kenji Miyazawa!" Trophy - Punchline (EU) (PS4)". PlayStationTrophies.org. 25 September 2018. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

Bibliography

Works in English translation

- Miyazawa, Kenji. The Milky Way Railroad. Translated by Joseph Sigrist and D. M. Stroud. Stone Bridge Press (1996). ISBN 1-880656-26-4

- Miyazawa Kenji. Night of the Milky Way Railroad. M.E. Sharpe (1991). ISBN 0-87332-820-5

- Miyazawa Kenji. The Restaurant of Many Orders. RIC Publications (2006). ISBN 1-74126-019-1

- Miyazawa Kenji. Miyazawa Kenji Selections. University of California Press (2007). ISBN 0-520-24779-5

- Miyazawa Kenji. Winds from Afar. Kodansha (1992).ISBN 087011171X

- Miyazawa Kenji. The Dragon and the Poet. translated by Massimo Cimarelli, Volume Edizioni (2013), ebook. ISBN 9788897747161

- Miyazawa Kenji. The Dragon and the Poet – illustrated version. Translated by Massimo Cimarelli. Illustrated by Francesca Eleuteri. Volume Edizioni (2013), ebook. ISBN 9788897747185

- Miyazawa Kenji. Once and Forever: The Tales of Kenji Miyazawa. Translated by John Bester. Kodansha International (1994). ISBN 4-7700-1780-4

- Miyazawa Kenji. Night Train to the Stars and other stories. Translated by John Bester, introduction by Kaori Nagai. Vintage Classics (2022). ISBN 9781784877767

- Snyder, Gary. The Back Country. New York: New Directions, 1967.

Adaptations

- Night on the Galactic Railroad (銀河鉄道の夜, Ginga Tetsudō no Yoru)

- The Life of Guskō Budori (グスコーブドリの伝記, Gusukō Budori no Denki)

- Matasaburo of the Wind (風の又三郎, Kaze no Matasaburō, Japanese Wikipedia)

- Gauche the Cellist (セロ弾きのゴーシュ, Sero Hiki no Gōshu)

- The Night of Taneyamagahara (種山ヶ原の夜, Taneyamagahara no Yoru)

Critical studies

- Cimarelli, Massimo. Miyazawa Kenji: A Short Biography, Volume Edizioni (2013), ebook. ASIN B00E0TE83W.

- Colligan-Taylor, Karen. The Emergence of Environmental Literature in Japan Environment, Garland 1990 pp. 34ff.

- Curley, Melissa Anne-Marie. "Fruit, Fossils, Footprints: Cathecting Utopia in the Work of Miyazawa Kenji", in Daniel Boscaljon (ed.), Hope and the Longing for Utopia: Futures and Illusions in Theology and Narrative, James Clarke & Co./ /Lutterworth Press, 2015. 96–118.

- Hara Shirō. Miyazawa Kenji Goi Jiten = Glossarial Dictionary of Miyazawa Kenji. Tokyo: Tokyo Shoseki, 1989.

- Holt, Jon. 2014. "Ticket to Salvation: Nichiren Buddhism in Miyazawa Kenji's Ginga tetsudō no yoru", Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 41/2: 305–345.

- Keene, Donald (1999). Dawn to the West: Japanese Literature of the Modern Era -- Poetry, Drama, Criticism. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231114394. (First Edition 1984; 1999 Columbia University Press paperback reprint cited in text)

- Kikuchi, Yūko (菊地有子), Japanese Modernisation and Mingei Theory: Cultural Nationalism and Oriental Orientalism, RoutledgeCurzon 2004 pp. 36ff.

- Kilpatrick, Helen Miyazawa Kenji and His Illustrators: Images of Nature and Buddhism in Japanese Children's Literature, BRILL, 2014.

- Inoue, Kota "Wolf Forest, Basket Forest and Thief Forest", in Mason, Michele and Lee, Helen (eds.), Reading Colonial Japan: Text, Context, and Critique, Stanford University Press, 2012 pp. 181–207,

- Long, Hoyt On Uneven Ground: Miyazawa Kenji and the Making of Place in Modern Japan, Stanford University Press, 2011

- Mitsutani, Margaret, "The Regional as the Center: The Poetry of Miyazawa Kenji", in Klaus Martens, Paul Duncan Morris, Arlette Warken (eds.) A World of Local Voices: Poetry in English Today, Königshausen & Neumann, 2003 pp. 66–72.

- Miyakubo, Hitomi; Matsukawa, Toshihiro (May 7, 2013). "Development of teaching materials for poetry: With close attention to Matsu no Hari by Miyazawa Kenji" (PDF). Bulletin of Nara University of Education. Nara University of Education. 62 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- Miyazawa Kenji 1968. Nihon no Shiika series. Chūō Kōron Sha.

- Nabeshima, Naoki, ed. (November 14, 2005). "Compassion for All Beings: The Realm of Kenji Miyazawa" (PDF). Ryukoku University official website. Ryukoku University Open Research Center for Humanities, Science, and Religion Open Research Center for Humanities, Science, and Religion. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- Nakamura, Minoru (1972). Miyazawa Kenji. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō. ISBN 978-4480011916.

- Napier, Susan, The Fantastic in Modern Japanese Literature: The Subversion of Modernity, Routledge 1996 pp. 141–178

- Pulvers, Roger (2007). Miyazawa, Kenji (ed.). Strong in the Rain: Selected Poems. Trans. Roger Pulvers. Bloodaxe Books. ISBN 978-1-85224-781-2.

- Sato, Hiroaki. "Introduction". In Miyazawa Kenji. Miyazawa Kenji Selections. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007. pp. 1–58. ISBN 0-520-24779-5.

- Seki, Tokuya (1971). Kenji Zuimon. Kadokawa Shoten.

- Stone, Jacqueline. 2003. "By Imperial Edict and Shogunal Decree: politics and the issue of the ordination platform in modern lay Nichiren Buddhism". IN: Steven Heine; Charles S. Prebish (ed.) Buddhism in the Modern World. New York: Oxford University Press. 2003. ISBN 0195146972. pp 193–219.

- Strong, Sarah. "The Reader's Guide" In Miyazawa Kenji, The Night of the Milky Way Railway. Translated by Sarah Strong. New York: 1991.

- Strong, Sarah. "The Poetry of Miyazawa Kenji". Thesis (Ph.D.), The University of Chicago, 1984.

- Ueda, Makoto, Modern Japanese Poets and the Nature of Literature. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1983.

External links

- e-texts of Kenji Miyazawa's works at Aozora Bunko

- The Miyazawa Kenji Museum in Hanamaki

- Kenji Miyazawa's grave

- Public Domain Audiobooks of Kenji Miyazawa's works at Japanese Classical Literature at Bedtime

- Works by or about Kenji Miyazawa at Internet Archive

- Works by Kenji Miyazawa at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)