Borda count

The Borda count is a family of positional voting rules which gives each candidate, for each ballot, a number of points corresponding to the number of candidates ranked lower. In the original variant, the lowest-ranked candidate gets 0 points, the next-lowest gets 1 point, etc., and the highest-ranked candidate gets n − 1 points, where n is the number of candidates. Once all votes have been counted, the option or candidate with the most points is the winner. The Borda count is intended to elect broadly acceptable options or candidates, rather than those preferred by a majority, and so is often described as a consensus-based voting system rather than a majoritarian one.[1]

| Part of the Politics series |

| Electoral systems |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

The Borda count was developed independently several times, being first proposed in 1435 by Nicholas of Cusa (see History below),[2][3][4][5] but is named for the 18th-century French mathematician and naval engineer Jean-Charles de Borda, who devised the system in 1770. It is currently used to elect two ethnic minority members of the National Assembly of Slovenia,[6] in modified forms to determine which candidates are elected to the party list seats in Icelandic parliamentary elections, and for selecting presidential election candidates in Kiribati. A variant known as the Dowdall system is used to elect members of the Parliament of Nauru.[7] Until the early 1970s, another variant was used in Finland to select individual candidates within party lists. It is also used throughout the world by various private organizations and competitions.

In the Modified Borda count, any unranked options receive 0 points, the lowest ranked receives 1, the next-lowest receives 2, etc., up to a possible maximum of n points for the highest ranked option if all options are ranked. The Quota Borda system is another variant used to attain proportional representation in multiwinner voting.

Voting and counting

Ballot

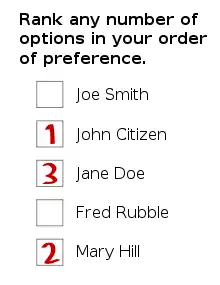

The Borda count is a ranked voting system: the voter ranks the list of candidates in order of preference. So, for example, the voter gives a 1 to their most preferred candidate, a 2 to their second most preferred, and so on. In this respect, it is the same as elections under systems such as instant-runoff voting, the single transferable vote or Condorcet methods. The integer-valued ranks for evaluating the candidates were justified by Laplace, who used a probabilistic model based on the law of large numbers.[5]

The Borda count is classified as a positional voting system, that is, all preferences are counted but at different values. Other positional methods include approval voting. By contrast, instant-runoff voting and single transferable voting use preferential voting, as the Borda count does, but in those systems secondary preferences are contingency votes, only used where the higher preference has been found to be ineffective.

There are a number of ways of scoring candidates under the Borda system, and it has a variant (the Dowdall system) which is significantly different.

There are also alternative ways of handling ties. This is a minor detail in which erroneous decisions can increase the risk of tactical manipulation; it is discussed in detail below.

Tournament-style counting

Each candidate is assigned a number of points from each ballot equal to the number of candidates to whom he or she is preferred, so that with n candidates, each one receives n – 1 points for a first preference, n – 2 for a second, and so on.[8] The winner is the candidate with the largest total number of points. For example, in a four-candidate election, the number of points assigned for the preferences expressed by a voter on a single ballot paper might be:

| Ranking | Candidate | Formula | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Andrew | n − 1 | 3 |

| 2nd | Brian | n − 2 | 2 |

| 3rd | Catherine | n − 3 | 1 |

| 4th | David | n − 4 | 0 |

Suppose that there are 3 voters, U, V and W, of whom U and V rank the candidates in the order A-B-C-D while W ranks them B-C-D-A.

| Candidate | U Points | V Points | W points | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrew | 3 | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| Brian | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| Catherine | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| David | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Thus Brian is elected.

A longer example, based on a fictitious election for Tennessee state capital, is shown below.

Borda's original counting

As Borda proposed the system, each candidate received one more point for each ballot cast than in tournament-style counting, eg. 4-3-2-1 instead of 3-2-1-0. This counting method is used in the Slovenian parliamentary elections for 2 out of 90 seats.[7]

Applied to the preceding example Borda's counting would lead to the following result, in which each candidate receives 3 more points than under tournament counting.

| Candidate | U points | V points | W points | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrew | 4 | 4 | 1 | 9 |

| Brian | 3 | 3 | 4 | 10 |

| Catherine | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| David | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

Tournament-style counting will be assumed in the remainder of this article.

Dowdall system (Nauru)

The island nation of Nauru uses a variant called the Dowdall system:[9][7] the voter awards the first-ranked candidate with 1 point, while the 2nd-ranked candidate receives 1⁄2 a point, the 3rd-ranked candidate receives 1⁄3 of a point, etc. (A similar system of weighting lower-preference votes was used in the 1925 Oklahoma primary electoral system.) Using the above example, in Nauru the point distribution among the four candidates would be this:

| Ranking | Candidate | Formula | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Andrew | 1/1 | 1.00 |

| 2nd | Brian | 1/2 | 0.50 |

| 3rd | Catherine | 1/3 | 0.33 |

| 4th | David | 1/4 | 0.25 |

This method is more favorable to candidates with many first preferences than the conventional Borda count. It has been described as a system "somewhere between plurality and the Borda count, but as veering more towards plurality".[7] Simulations show that 30% of Nauru elections would produce different outcomes if counted using standard Borda rules.[7]

The system was devised by Nauru's Secretary for Justice, Desmond Dowdall, an Irishman, in 1971.[7]

Properties

Elections as estimation procedures

Condorcet looked at an election as an attempt to combine estimators. Suppose that each candidate has a figure of merit and that each voter has a noisy estimate of the value of each candidate. The ballot paper allows the voter to rank the candidates in order of estimated merit. The aim of the election is to produce a combined estimate of the best candidate. Such an estimator can be more reliable than any of its individual components. Applying this principle to jury decisions, Condorcet derived his theorem that a large enough jury would always decide correctly.[10]

Peyton Young showed that the Borda count gives an approximately maximum likelihood estimator of the best candidate.[11] His theorem assumes that errors are independent, in other words, that if a voter Veronica rates a particular candidate highly, then there is no reason to expect her to rate "similar" candidates highly. If this property is absent – if Veronica gives correlated rankings to candidates with shared attributes – then the maximum likelihood property is lost, and the Borda count is subject to nomination effects: a candidate is more likely to be elected if there are similar candidates on the ballot.

Young showed that the Kemeny–Young method was the exact maximum likelihood estimator of the ranking of candidates. It implies a voting procedure which satisfies the Condorcet criterion but is computationally burdensome.

Effect of irrelevant candidates

.png.webp)

The Borda count is particularly susceptible to distortion through the presence of candidates who do not themselves come into consideration, even when the voters lie along a spectrum. Voting systems which satisfy the Condorcet criterion are protected against this weakness since they automatically also satisfy the median voter theorem, which says that the winner of an election will be the candidate preferred by the median voter regardless of which other candidates stand.

Suppose that there are 11 voters whose positions along the spectrum can be written 0, 1, ..., 10, and suppose that there are 2 candidates, Andrew and Brian, whose positions are as shown:

| Candidate | A | B |

|---|---|---|

| Position | 51⁄4 | 61⁄4 |

The median voter Marlene is at position 5, and both candidates are to her right, so we would expect A to be elected. We can verify this for the Borda system by constructing a table to illustrate the count. The main part of the table shows the voters who prefer the first to the second candidate, as given by the row and column headings, while the additional column to the right gives the scores for the first candidate.

2nd 1st |

A | B | score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | — | 0–5 | 6 | |

| B | 6–10 | — | 5 |

A is indeed elected.

But now suppose that two additional candidates, further to the right, enter the election.

| Candidate | A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | 51⁄4 | 61⁄4 | 81⁄4 | 101⁄4 |

The counting table expands as follows:

2nd 1st |

A | B | C | D | score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | — | 0–5 | 0–6 | 0–7 | 21 | |

| B | 6–10 | — | 0–7 | 0–8 | 22 | |

| C | 7–10 | 8–10 | — | 0–9 | 17 | |

| D | 8–10 | 9–10 | 10 | — | 6 |

The entry of two dummy candidates allows B to win the election.

This example bears out the comment of the Marquis de Condorcet, who argued that the Borda count "relies on irrelevant factors to form its judgments" and was consequently "bound to lead to error".[7]

Other properties

There are a number of formalised voting system criteria whose results are summarised in the following table.

| System | Monotonic | Condorcet winner | Majority | Condorcet loser | Majority loser | Mutual majority | Smith | ISDA | LIIA | Independence of clones | Reversal symmetry | Participation, consistency | Laternoharm | Laternohelp | Polynomial time | Resolvability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schulze | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Ranked pairs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Tideman's Alternative | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Kemeny–Young | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Copeland | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Nanson | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Black | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Instant-runoff voting | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Smith/IRV | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Borda | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Baldwin | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Bucklin | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Plurality | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Contingent voting | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Coombs[12] | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| MiniMax | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Anti-plurality[12] | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Sri Lankan contingent voting | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Supplementary voting | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dodgson[12] | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

Simulations show that Borda has a high probability of choosing the Condorcet winner when one exists, in the absence of strategic voting and with all ballots ranking all candidates.[2][7]

Counting of ties

Several different methods of handling ties have been suggested. They can be illustrated using the 4-candidate election discussed previously.

| Ranking | Candidate | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | Andrew | 3 |

| 2nd | Brian | 2 |

| 3rd | Catherine | 1 |

| 4th | David | 0 |

Tournament-style counting of ties

Tournament-style counting can be extended to allow ties anywhere in a voter's ranking by assigning each candidate half a point for every other candidate he or she is tied with, in addition to a whole point for every candidate he or she is strictly preferred to.

In the example, suppose that a voter is indifferent between Andrew and Brian, preferring both to Catherine and Catherine to David. Then Andrew and Brian will each receive 21⁄2 points, Catherine will receive 1, and David none. This is referred to as "averaging" by Narodytska and Walsh.[13]

Borda's original counting of ties

In Borda's system as originally proposed, ties were allowed only at the end of a voter's ranking, and each tied candidate was given the minimum number of points. So if a voter marks Andrew as his or her first preference, Brian as his or her second, and leaves Catherine and David unranked (called "truncating the ballot"), then Andrew will receive 3 points, Brian 2, and Catherine and David none. This is an example of what Narodytska and Walsh call "rounding up".

Modified Borda count

The "modified Borda count" again allows ties only at the end of a voter's ranking. It gives no points to unranked candidates, 1 point to the least preferred of the ranked candidates, etc. So if a voter ranks Andrew above Brian and leaves other candidates unranked, Andrew will receive 2 points, Brian will receive 1 point, and Catherine and David will receive none. This is equivalent to "rounding down". The most preferred candidate on a ballot paper will receive a different number of points depending on how many candidates were left unranked.

Comparison of methods of counting ties

Rounding up penalises unranked candidates (they share fewer points than they would if they were ranked), while rounding down rewards them. Both methods encourage undesirable behaviour from voters.

First example (bias of rounding down)

Suppose that there are two candidates: A with 100 supporters and C with 80. A will win by 100 points to 80.

Now suppose that a third candidate B is introduced, who is a clone of C, and that the modified Borda count is used. Voters who prefer B and C to A have no way of indicating indifference between them, so they will choose a first preference at random, voting either B-C-A or C-B-A. Supporters of A can show a tied preference between B and C by leaving them unranked (although this is not possible in Nauru). B and C will each receive about 120 votes, while A receives 100.

But if A can persuade his supporters to rank B and C randomly, he will win with 200 points, while B and C each receive about 170.

If ties were averaged (i.e. used tournament counting), then the appearance of B as a clone of C would make no difference to the result; A would win as before, regardless of whether voters truncated their ballots or made random choices between B and C.

Second example (bias of rounding up)

A similar example can be constructed to show the bias of rounding down. Suppose that A and C are as before, but that B is now a near-clone of A, preferred to A by male voters but rated lower by females. About 50 voters will vote A-B-C, about 50 B-A-C, about 40 C-A-B and about 40 C-B-A. A and B will each receive about 190 votes, while C will receive 160.

But if ties are resolved according to Borda's proposal, and if C can persuade her supporters to leave A and B unranked, then there will be about 50 A-B-C ballots, about 50 B-A-C and 80 truncated to just C. A and B will each receive about 150 votes, while C receives 160.

Again, if tournament counting of ties was used, truncating ballots would make no difference, and the winner would be either A or B.

Interpretation of examples of ties

Borda's method has often been accused of being susceptible to tactical voting, which is partly due to its association with biased methods of handling ties. The French Academy of Sciences (of which Borda was a member) experimented with Borda's system but abandoned it, in part because "the voters found how to manipulate the Borda rule: not only by putting their most dangerous rival at the bottom of their lists, but also by truncating their lists".[14] In response to the issue of strategic manipulation in the Borda count, M. de Borda said: "My scheme is intended for only honest men".[8][14]

Tactical voting is common in Slovenia, where truncated ballots are allowed; a majority of voters bullet-vote, with only 42% of voters ranking a second-preference candidate. As with Borda's original proposal, ties are handled by rounding down (or sometimes by ultra-rounding, unranked candidates being given one less point than the minimum for ranked candidates).[7]

Ties in the Dowdall system

Ties are not allowed: Nauru voters are required to rank all candidate, and ballots that fail to do so are rejected.[7]

Truncated ballots

Some implementations of Borda voting require voters to truncate their ballots to a certain length:

- In Kiribati, a variant is employed which uses a traditional Borda formula, but in which voters rank only four candidates, irrespective of how many are standing.[15]

- In Toastmasters International, speech contests are truncation-scored as 3, 2, 1 for the top-three ranked candidates. Ties are broken by having a special ballot that is ignored unless there is a tie.[16]

Multiple winners

The system invented by Borda was intended for use in elections with a single winner, but it is also possible to conduct a Borda count with more than one winner, by recognizing the desired number of candidates with the most points as the winners. In other words, if there are two seats to be filled, then the two candidates with most points win; in a three-seat election, the three candidates with most points, and so on. In Nauru, which uses the multi-seat variant of the Borda count, parliamentary constituencies of two and four seats are used.

The quota Borda system is a system of proportional representation in multi-seat constituencies that uses the Borda count. Chris Geller's STV-B uses vote count quotas to elect, but eliminates the candidate with the lowest Borda score; Geller-STV does not recalculate Borda scores after partial vote transfers, meaning partial-transfer of votes affects voting power for election but not for elimination.

Related systems

Nanson's and Baldwin's methods are Condorcet-consistent voting methods based on the Borda score. Both are run as series of elimination rounds analogous to instant-runoff voting. In the first case, in each round every candidate with less than the average Borda score is eliminated; in the second, the candidate with lowest score is eliminated. Unlike the Borda count, Nanson and Baldwin are majoritarian and Condorcet methods because they use the fact that a Condorcet winner always has a higher-than-average Borda score relative to other candidates, and the Condorcet loser a lower than average Borda score.[17] However they are not monotonic.

Potential for tactical manipulation

Borda counts are vulnerable to manipulation by both tactical voting and strategic nomination. The Dowdall system may be more resistant, based on observations in Kiribati using the modified Borda count versus Nauru using the Dowdall system,[9] but little research has been done thus far on the Nauru system.

Tactical voting

Borda counts are unusually vulnerable to tactical voting, even compared to most other voting systems.[18] Voters who vote tactically, rather than via their true preference, will be more influential; more alarmingly, if everyone starts voting tactically, the result tends to approach a large tie that will be decided semi-randomly. When a voter utilizes compromising, they insincerely raise the position of a second or third choice candidate over their first choice candidate, in order to help the second choice candidate to beat a candidate they like even less. When a voter utilizes burying, voters can help a more-preferred candidate by insincerely lowering the position of a less-preferred candidate on their ballot. Combining both these strategies can be powerful, especially as the number of candidates in an election increases. For example, if there are two candidates whom a voter considers to be the most likely to win, the voter can maximise his impact on the contest between these front runners by ranking the candidate whom he likes more in first place, and ranking the candidate whom he likes less in last place. If neither front runner is his sincere first or last choice, the voter is employing both the compromising and burying tactics at once; if enough voters employ such strategies, then the result will no longer reflect the sincere preferences of the electorate.

For an example of how potent tactical voting can be, suppose a trip is being planned by a group of 100 people on the East Coast of North America. They decide to use Borda count to vote on which city they will visit. The three candidates are New York City, Orlando, and Iqaluit. 48 people prefer Orlando / New York / Iqaluit; 44 people prefer New York / Orlando / Iqaluit; 4 people prefer Iqaluit / New York / Orlando; and 4 people prefer Iqaluit / Orlando / New York. If everyone votes their true preference, the result is:

- Orlando:

- New York:

- Iqaluit:

If the New York voters realize that they are likely to lose and all agree to tactically change their stated preference to New York / Iqaluit / Orlando, burying Orlando, then this is enough to change the result in their favor:

- New York:

- Orlando:

- Iqaluit:

In this example, only a few of the New York voters needed to change their preference to tip this result because it was so close – just five voters would have been sufficient had everyone else still voted their true preferences. However, if Orlando voters realize that the New York voters are planning on tactically voting, they too can tactically vote for Orlando / Iqaluit / New York. When all of the New York and all of the Orlando voters do this, however, there is a surprising new result:

- Iqaluit:

- Orlando:

- New York:

The tactical voting has overcorrected, and now the clear last place option is a threat to win, with all three options extremely close. Tactical voting has entirely obscured the true preferences of the group into a large near-tie.

Strategic nomination

The Borda count is highly vulnerable to a form of strategic nomination called teaming or cloning. This means that when more candidates run with similar ideologies, the probability of one of those candidates winning increases. This is illustrated by the example 'Effect of irrelevant alternatives' above. Therefore, under the Borda count, it is to a faction's advantage to run as many candidates as it can. For example, even in a single-seat election, it would be to the advantage of a political party to stand as many candidates as possible in an election. In this respect, the Borda count differs from many other single-winner systems, such as the 'first past the post' plurality system, in which a political faction is disadvantaged by running too many candidates. Under systems such as plurality, 'splitting' a party's vote in this way can lead to the spoiler effect, which harms the chances of any of a faction's candidates being elected.

Strategic nomination is used in Nauru, according to MP Roland Kun, with factions running multiple "buffer candidates" who are not expected to win, to lower the tallies of their main competitors.[7]

Example

Imagine that Tennessee is having an election on the location of its capital. The population of Tennessee is concentrated around its four major cities, which are spread throughout the state. For this example, suppose that the entire electorate lives in these four cities and that everyone wants to live as near to the capital as possible.

The candidates for the capital are:

- Memphis, the state's largest city, with 42% of the voters, but located far from the other cities

- Nashville, with 26% of the voters, near the center of the state

- Knoxville, with 17% of the voters

- Chattanooga, with 15% of the voters

The preferences of the voters would be divided like this:

| 42% of voters (close to Memphis) |

26% of voters (close to Nashville) |

15% of voters (close to Chattanooga) |

17% of voters (close to Knoxville) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Thus voters are assumed to prefer candidates in order of proximity to their home town. We get the following point counts per 100 voters:

Voters Candidate | Memphis | Nashville | Knoxville | Chattanooga | Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memphis | 42×3=126 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 126 | |

| Nashville | 42×2 = 84 | 26×3 = 78 | 17×1 = 17 | 15×1 = 15 | 194 | |

| Knoxville | 0 | 26×1 = 26 | 17×3 = 51 | 15×2 = 30 | 107 | |

| Chattanooga | 42×1 = 42 | 26×2 = 52 | 17×2 = 34 | 15×3 = 45 | 173 |

Accordingly Nashville is elected.

Current uses

Political uses

The Borda count is used for certain political elections in at least three countries, Slovenia and the tiny Micronesian nations of Kiribati and Nauru.

In Slovenia, the Borda count is used to elect two of the ninety members of the National Assembly: one member represents a constituency of ethnic Italians, the other a constituency of the Hungarian minority.

Members of the Parliament of Nauru are elected based on a variant of the Borda count that involves two departures from the normal practice: (1) multi-seat constituencies, of either two or four seats, and (2) a point-allocation formula that involves increasingly small fractions of points for each ranking, rather than whole points.

In Kiribati, the president (or Beretitenti) is elected by the plurality system, but a variant of the Borda count is used to select either three or four candidates to stand in the election. The constituency consists of members of the legislature (Maneaba). Voters in the legislature rank only four candidates, with all other candidates receiving zero points. Since at least 1991, tactical voting has been an important feature of the nominating process.

The Republic of Nauru became independent from Australia in 1968. Before independence, and for three years afterwards, Nauru used instant-runoff voting, importing the system from Australia, but since 1971, a variant of the Borda count has been used.

The modified Borda count has been used by the Green Party of Ireland to elect its chairperson.[19][20]

The Borda count has been used for non-governmental purposes at certain peace conferences in Northern Ireland, where it has been used to help achieve consensus between participants including members of Sinn Féin, the Ulster Unionists, and the political wing of the UDA.

Other uses

The Borda count is used in elections by some educational institutions in the United States:

- University of Michigan

- Central Student Government

- Student Government of the College of Literature, Science and the Arts (LSASG)

- University of Missouri: officers of the Graduate-Professional Council

- University of California Los Angeles: officers of the Graduate Student Association

- Harvard University: members of the Undergraduate Council, as of 2018 [21]

- Southern Illinois University at Carbondale: officers of the Faculty Senate,

- Arizona State University: officers of the Department of Mathematics and Statistics assembly.

- Wheaton College, Massachusetts: faculty members of committees.

- College of William and Mary: members of the faculty personnel committee of the School of Business Administration (tie-breaker).

The Borda count is used in elections by some professional and technical societies:

- International Society for Cryobiology: Board of Governors.

- U.S. Wheat and Barley Scab Initiative: members of Research Area Committees.

- X.Org Foundation: Board of Directors.

The OpenGL Architecture Review Board uses the Borda count as one of the feature-selection methods.

The Borda count is used to determine winners for the World Champion of Public Speaking contest organized by Toastmasters International. Judges offer a ranking of their top three speakers, awarding them three points, two points, and one point, respectively. All unranked candidates receive zero points.

The modified Borda count is used to elect the President for the United States member committee of AIESEC.

The Eurovision Song Contest uses a heavily modified form of the Borda count, with a different distribution of points: only the top ten entries are considered in each ballot, the favorite entry receiving 12 points, the second-placed entry receiving 10 points, and the other eight entries getting points from 8 to 1. Although designed to favor a clear winner, it has produced very close races and even a tie.

The Borda count is used for wine trophy judging by the Australian Society of Viticulture and Oenology, and by the RoboCup autonomous robot soccer competition at the Center for Computing Technologies, in the University of Bremen in Germany.

The Finnish Associations Act lists three different modifications of the Borda count for holding a proportional election. All the modifications use fractions, as in Nauru. A Finnish association may choose to use other methods of election, as well.[22]

Sports awards

The Borda count is a popular method for granting sports awards. American uses include:

- MLB Most Valuable Player Award (baseball)

- Heisman Trophy (college football)[23]

- Ranking of NCAA college teams, including in the AP Poll and Coaches Poll

In information retrieval

The Borda count has been proposed as a rank aggregation method in information retrieval, in which documents are ranked according to multiple criteria and the resulting rankings are then combined into a composite ranking. In this method, the ranking criteria are treated as voters, and the aggregate ranking is the result of applying the Borda count to their "ballots".[24]

Analogy with sporting tournaments

Sporting tournaments frequently seek to produce a ranking of competitors from pairwise matches, in each of which a single point is awarded for a win, half a point for a draw, and no points for a loss. (Sometimes the scores are doubled as 2/1/0.) This is analogous to a Borda count in which each preference expressed by a single voter between two candidates is equivalent to a sporting fixture; it is also analogous to Copeland's method supposing that the electorate's overall preference between two candidates takes the place of a sporting fixture.

This scoring system was adopted for international chess around the middle of the nineteenth century and by the English Football League in 1888–1889. Unbiased handling of draws was therefore adopted a century before unbiased handling of ties was recognised as desirable in electoral systems.

History

The Borda count is thought to have been developed independently at least four times:

- Ramon Llull (1232–1315/16) described the election of an abbess in the 1283 novel Blanquerna. The election process is equivalent to the second of Borda's two equivalent definitions of the Borda count.[25]

- Nicholas of Cusa (1401–1464) in his "De Concordantia Catholica" (1433) provided the first description of the Borda count and argued unsuccessfully for its use in the election of the Holy Roman Emperor. Cusa is known to have read another of Llull's pamphlets but presents a different definition and appears either to have been unaware of the Blanquerna method or not to realized it was equivalent.[26]

- Jean-Charles de Borda (1733–1799) devised the system as a fair way to elect members to the French Academy of Sciences in a paper presented to the Academy in 1784 and published as "Mémoire sur les élections au scrutin" in Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences, Paris.[27] The Borda count was the sole method used for membership election to the Academy from 1795 until 1800, when it was supplemented by other methods at the urging of Napoleon.

- Charles L. Dodgson (Lewis Carroll, 1832–1898) proposed a version of the Borda count in "A discussion of the various methods of procedure in conducting elections" (1783) for a vote to assign a fellowship at Christ Church, Oxford. The fellows voted using the method, realized that there was a Condorcet winner who did not win (a violation of the Condorcet Criterion), rejected the results, and awarded the fellowship to the Condorcet winner.[28] The next year, Dodgson proposed replacing his Borda count method with one similar to Copeland's method, then in 1876 proposed a hybrid of the two in "A method of taking votes on more than two issues". He appears to have been unaware of either Borda or Condorcet's work.[29]

See also

Notes

- Lippman, David. "Voting Theory" (PDF). Math in Society.

Borda count is sometimes described as a consensus-based voting system, since it can sometimes choose a more broadly acceptable option over the one with majority support.

- Emerson, Peter (16 January 2016). From Majority Rule to Inclusive Politics. Springer. ISBN 9783319235004.

- Emerson, Peter (1 February 2013). "The original Borda count and partial voting". Social Choice and Welfare. 40 (2): 353–358. doi:10.1007/s00355-011-0603-9. ISSN 0176-1714. S2CID 29826994.

- Actually, Nicholas' system used higher numbers for more-preferred candidates.

- Tangian, Andranik (2020). Analytical theory of democracy. Vols. 1 and 2. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. pp. 99–101, 132ff. ISBN 978-3-030-39690-9.

- "Slovenia's electoral law". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- Fraenkel, Jon; Grofman, Bernard (3 April 2014). "The Borda Count and its real-world alternatives: Comparing scoring rules in Nauru and Slovenia". Australian Journal of Political Science. 49 (2): 186–205. doi:10.1080/10361146.2014.900530. S2CID 153325225.

- Black, Duncan (1987) [1958]. The Theory of Committees and Elections. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9780898381894.

- Reilly, Benjamin (2002). "Social Choice in the South Seas: Electoral Innovation and the Borda Count in the Pacific Island Countries". International Political Science Review. 23 (4): 364–366. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.924.3992. doi:10.1177/0192512102023004002. S2CID 3213336.

- Eric Pacuit, "Voting Methods", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

- H. P. Young, "Condorcet's Theory of Voting" (1988).

- Anti-plurality, Coombs and Dodgson are assumed to receive truncated preferences by apportioning possible rankings of unlisted alternatives equally; for example, ballot A > B = C is counted as 1/2 A > B > C and 1/2 A > C > B. If these methods are assumed not to receive truncated preferences, then later-no-harm and later-no-help are not applicable.

- Nina Narodytska and Toby Walsh, "The Computational Impact of Partial Votes on Strategic Voting" (2014).

- McLean, Iain; Urken, Arnold B.; Hewitt, Fiona (1995). Classics of Social Choice. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472104505.

- Reilly, Benjamin. "Social Choice in the South Seas: Electoral Innovation and the Borda Count in the Pacific Island Countries" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2006.

- SPEECH CONTEST RULEBOOK JULY 1, 2017 TO JUNE 30, 2018

- https://www.cs.rpi.edu/~xial/COMSOC18/papers/COMSOC2018_paper_33.pdf

- J. Green-Armytage, T. N. Tideman and R. Cosman, ‘Statistical Evaluation of Voting Rules’ (2015).

- Voting Systems

- Emerson, Peter (2007) Designing an All-Inclusive Democracy. Springer Verlag, Part 1, pp. 15–38 "Collective Decision-making: The Modified Borda Count, MBC" ISBN 978-3540331636 (Print) ISBN 978-3540331643 (Online)

- "Undergraduate Council Adopts New Voting Method for Elections | News | the Harvard Crimson".

- "Finnish Associations Act". National Board of Patents and Registration of Finland. Archived from the original on 1 March 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- Heisman.com – Heisman Trophy

- Dwork, Cynthia; Kumar, Ravi; Naor, Moni; Sivakumar, D. (May 2001). "Rank aggregation methods for the Web". Proceedings of the 10th international conference on World Wide Web. pp. 613–622. doi:10.1145/371920.372165. ISBN 1581133480. S2CID 8393813.

- Iain McLean, "The Borda and Condorcet Principles: Three Medieval Applications," p. 102.

- Iain McLean, "The Borda and Condorcet Principles: Three Medieval Applications," pp. 105–106.

- The article appeared in the 1781 edition of the Histoire, and Borda himself asserted he had publicized these ideas as early as 1770, but 1784 appears to be the correct date of attribution. Brian, É, "Condorcet and Borda in 1784. Misfits and Documents", Electronic Journal for History of Probability and Statistics',' Vol. 4, No. 1 (June 2008).

- Iain McLean, "Voting." The Mathematical World of Charles L. Dodgson (Lewis Carroll). Wilson, Robin, and Amirouche Moktefi, eds. Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Iain McLean, "Voting", pp. 123–124.

Further reading

- George G. Szpiro, 'Numbers Rule' (2010), a popular account of the history of the study of voting methods.

- Emerson, Peter (2007). Designing an All-Inclusive Democracy - Consensual Voting Procedures for use in Parliaments, Councils and Committees. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3540331636. (Print) ISBN 978-3540331643 (online)

- Reilly, Benjamin (2002). "Social Choice in the South Seas: Electoral Innovation and the Borda Count in the Pacific Island Countries". International Political Science Review. 23 (4): 355–372. doi:10.1177/0192512102023004002. S2CID 3213336.

- Saari, Donald G. (2000). "Mathematical Structure of Voting Paradoxes: II. Positional Voting". Journal of Economic Theory. 15 (1): 511–528. doi:10.1007/s001990050002. S2CID 195227181. SSRN 195769.

- Saari, Donald G. (2001). Chaotic Elections!. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0821828472. Describes various voting systems using a mathematical model, and supports the use of the Borda count.

- Saari, Donald G. (2008). Disposing Dictators, Demystifying Voting Paradoxes: Social Choice Analysis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521516051. This expository, largely non-technical book is the first to find positive results showing that the situation is not anywhere as dire and negative as we have been led to believe.

- Toplak, Jurij (2006). "The parliamentary election in Slovenia, October 2004". Electoral Studies. 25 (4): 825–831. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2005.12.006.

- Adelsman, Rony M.; Whinston, Andrew B. (1977). "Sophisticated Voting with Information for Two Voting Functions". Journal of Economic Theory. 15 (1): 145–159. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(77)90073-4.

- Hulkower, Neal D. and Neatrour, John (2019). "The Power of None", Sage Open. This paper looks at adding None of the candidates as a binding option for the Borda Count and proves that it uniquely satisfies five rational properties.

External links

- Eric Pacuit, "Voting Methods", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- The de Borda Institute, Northern Ireland

- Voters Choose, USA: A Borda Count advocacy and research group based in the United States

- Complexity of Control of Borda Count Elections: thesis by Nathan F. Russell

- Scoring Rules on Dichotomous Preferences: article by Marc Vorsatz, mathematically comparing the Borda count to approval voting under specific conditions.

- A program to implement the Condorcet and Borda rules in a small-n election: article by Iain McLean and Neil Shephard.

- (in French) Élections au scrutin: Borda's original French text (1781) in a high definition PDF file.

- QuickVote – A website that calculates Borda count results. For comparison, it also calculates the winner according to plurality, instant-runoff, Kemeny–Young , and other voting methods.