Molecular modelling

Molecular modelling encompasses all methods, theoretical and computational, used to model or mimic the behaviour of molecules.[1] The methods are used in the fields of computational chemistry, drug design, computational biology and materials science to study molecular systems ranging from small chemical systems to large biological molecules and material assemblies. The simplest calculations can be performed by hand, but inevitably computers are required to perform molecular modelling of any reasonably sized system. The common feature of molecular modelling methods is the atomistic level description of the molecular systems. This may include treating atoms as the smallest individual unit (a molecular mechanics approach), or explicitly modelling protons and neutrons with its quarks, anti-quarks and gluons and electrons with its photons (a quantum chemistry approach).

Molecular mechanics

Molecular mechanics is one aspect of molecular modelling, as it involves the use of classical mechanics (Newtonian mechanics) to describe the physical basis behind the models. Molecular models typically describe atoms (nucleus and electrons collectively) as point charges with an associated mass. The interactions between neighbouring atoms are described by spring-like interactions (representing chemical bonds) and Van der Waals forces. The Lennard-Jones potential is commonly used to describe the latter. The electrostatic interactions are computed based on Coulomb's law. Atoms are assigned coordinates in Cartesian space or in internal coordinates, and can also be assigned velocities in dynamical simulations. The atomic velocities are related to the temperature of the system, a macroscopic quantity. The collective mathematical expression is termed a potential function and is related to the system internal energy (U), a thermodynamic quantity equal to the sum of potential and kinetic energies. Methods which minimize the potential energy are termed energy minimization methods (e.g., steepest descent and conjugate gradient), while methods that model the behaviour of the system with propagation of time are termed molecular dynamics.

This function, referred to as a potential function, computes the molecular potential energy as a sum of energy terms that describe the deviation of bond lengths, bond angles and torsion angles away from equilibrium values, plus terms for non-bonded pairs of atoms describing van der Waals and electrostatic interactions. The set of parameters consisting of equilibrium bond lengths, bond angles, partial charge values, force constants and van der Waals parameters are collectively termed a force field. Different implementations of molecular mechanics use different mathematical expressions and different parameters for the potential function.[2] The common force fields in use today have been developed by using chemical theory, experimental reference data, and high level quantum calculations. The method, termed energy minimization, is used to find positions of zero gradient for all atoms, in other words, a local energy minimum. Lower energy states are more stable and are commonly investigated because of their role in chemical and biological processes. A molecular dynamics simulation, on the other hand, computes the behaviour of a system as a function of time. It involves solving Newton's laws of motion, principally the second law, . Integration of Newton's laws of motion, using different integration algorithms, leads to atomic trajectories in space and time. The force on an atom is defined as the negative gradient of the potential energy function. The energy minimization method is useful to obtain a static picture for comparing between states of similar systems, while molecular dynamics provides information about the dynamic processes with the intrinsic inclusion of temperature effects.

Variables

Molecules can be modelled either in vacuum, or in the presence of a solvent such as water. Simulations of systems in vacuum are referred to as gas-phase simulations, while those that include the presence of solvent molecules are referred to as explicit solvent simulations. In another type of simulation, the effect of solvent is estimated using an empirical mathematical expression; these are termed implicit solvation simulations.

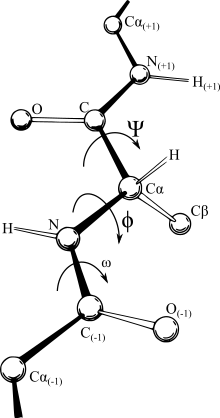

Coordinate representations

Most force fields are distance-dependent, making the most convenient expression for these Cartesian coordinates. Yet the comparatively rigid nature of bonds which occur between specific atoms, and in essence, defines what is meant by the designation molecule, make an internal coordinate system the most logical representation. In some fields the IC representation (bond length, angle between bonds, and twist angle of the bond as shown in the figure) is termed the Z-matrix or torsion angle representation. Unfortunately, continuous motions in Cartesian space often require discontinuous angular branches in internal coordinates, making it relatively hard to work with force fields in the internal coordinate representation, and conversely a simple displacement of an atom in Cartesian space may not be a straight line trajectory due to the prohibitions of the interconnected bonds. Thus, it is very common for computational optimizing programs to flip back and forth between representations during their iterations. This can dominate the calculation time of the potential itself and in long chain molecules introduce cumulative numerical inaccuracy. While all conversion algorithms produce mathematically identical results, they differ in speed and numerical accuracy.[3] Currently, the fastest and most accurate torsion to Cartesian conversion is the Natural Extension Reference Frame (NERF) method.[3]

Applications

Molecular modelling methods are now used routinely to investigate the structure, dynamics, surface properties, and thermodynamics of inorganic, biological, and polymeric systems. A large number of molecular models of force field are today readily available in databases.[4][5] The types of biological activity that have been investigated using molecular modelling include protein folding, enzyme catalysis, protein stability, conformational changes associated with biomolecular function, and molecular recognition of proteins, DNA, and membrane complexes.[6]

See also

- Cheminformatics

- Comparison of force field implementations

- Comparison of nucleic acid simulation software

- Comparison of software for molecular mechanics modeling

- Density functional theory software

- List of molecular graphics systems

- List of protein structure prediction software

- List of software for Monte Carlo molecular modeling

- List of software for nanostructures modeling

- Molecular design software

- Molecular engineering

- Molecular graphics

- Molecular model

- Molecular modeling on GPU

- Molecule editor

- Monte Carlo method

- Quantum chemistry computer programs

- Semi-empirical quantum chemistry method

- Simulated reality

- Structural bioinformatics

- Z-matrix (mathematics)

References

- Leach AR (2009). Molecular modelling : principles and applications. Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-582-38210-7. OCLC 635267533.

- Heinz H, Ramezani-Dakhel H (January 2016). "Simulations of inorganic-bioorganic interfaces to discover new materials: insights, comparisons to experiment, challenges, and opportunities". Chemical Society Reviews. 45 (2): 412–48. doi:10.1039/C5CS00890E. PMID 26750724.

- Parsons J, Holmes JB, Rojas JM, Tsai J, Strauss CE (July 2005). "Practical conversion from torsion space to Cartesian space for in silico protein synthesis". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 26 (10): 1063–8. doi:10.1002/jcc.20237. PMID 15898109. S2CID 2279574.

- Stephan, Simon; Horsch, Martin T.; Vrabec, Jadran; Hasse, Hans (2019-07-03). "MolMod – an open access database of force fields for molecular simulations of fluids". Molecular Simulation. 45 (10): 806–814. doi:10.1080/08927022.2019.1601191. ISSN 0892-7022. S2CID 119199372.

- Eggimann, Becky L.; Sunnarborg, Amara J.; Stern, Hudson D.; Bliss, Andrew P.; Siepmann, J. Ilja (2014-01-02). "An online parameter and property database for the TraPPE force field". Molecular Simulation. 40 (1–3): 101–105. doi:10.1080/08927022.2013.842994. ISSN 0892-7022. S2CID 95716947.

- Lee J, Cheng X, Swails JM, Yeom MS, Eastman PK, Lemkul JA, et al. (January 2016). "CHARMM-GUI Input Generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM Simulations Using the CHARMM36 Additive Force Field". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 12 (1): 405–13. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00935. PMC 4712441. PMID 26631602.

Further reading

- Allen MP, Tildesley DJ (1989). Computer simulation of liquids. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-855645-4.

- Frenkel D, Smit B (1996). Understanding Molecular Simulation: From Algorithms to Applications. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-267370-0.

- Rapaport DC (2004). The Art of Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82568-7.

- Sadus RJ (2002). Molecular Simulation of Fluids: Theory, Algorithms and Object-Orientation. Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-51082-6.

- Ramachandran KI, Deepa G, Krishnan Namboori PK (2008). Computational Chemistry and Molecular Modeling Principles and Applications. Springer-Verlag GmbH. ISBN 978-3-540-77302-3.