Monarch butterfly

The monarch butterfly or simply monarch (Danaus plexippus) is a milkweed butterfly (subfamily Danainae) in the family Nymphalidae.[5] Other common names, depending on region, include milkweed, common tiger, wanderer, and black-veined brown.[6] It is amongst the most familiar of North American butterflies and an iconic pollinator,[7] although it is not an especially effective pollinator of milkweeds.[8][9] Its wings feature an easily recognizable black, orange, and white pattern, with a wingspan of 8.9–10.2 cm (3.5–4.0 in).[10] A Müllerian mimic, the viceroy butterfly, is similar in color and pattern, but is markedly smaller and has an extra black stripe across each hindwing.

| Monarch butterfly | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

| |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Family: | Nymphalidae |

| Genus: | Danaus |

| Species: | D. plexippus |

| Binomial name | |

| Danaus plexippus | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

_underside_Piedra_Herrada.jpg.webp)

Piedra Herrada, Mexico

The eastern North American monarch population is notable for its annual southward late-summer/autumn instinctive migration from the northern and central United States and southern Canada to Florida and Mexico.[5] During the fall migration, monarchs cover thousands of miles, with a corresponding multigenerational return north in spring. The western North American population of monarchs west of the Rocky Mountains often migrates to sites in southern California, but individuals have been found in overwintering Mexican sites, as well.[11][12] In 2009, monarchs were reared on the International Space Station, successfully emerging from pupae located in the station's Commercial Generic Bioprocessing Apparatus.[13]

Etymology

The name "monarch" is believed to have been given in honor of King William III of England, as the butterfly's main color is that of the king's secondary title, Prince of Orange.[14] The monarch was originally described by Carl Linnaeus in his Systema Naturae of 1758 and placed in the genus Papilio.[15] In 1780, Jan Krzysztof Kluk used the monarch as the type species for a new genus, Danaus.

Danaus (Ancient Greek Δαναός), a great-grandson of Zeus, was a mythical king in Egypt or Libya, who founded Argos; Plexippus (Πλήξιππος) was one of the 50 sons of Aegyptus, the twin brother of Danaus. In Homeric Greek, his name means "one who urges on horses", i.e., "rider" or "charioteer".[16] In the tenth edition of Systema Naturae, at the bottom of page 467,[17] Linnaeus wrote that the names of the Danai festivi, the division of the genus to which Papilio plexippus belonged, were derived from the sons of Aegyptus. Linnaeus divided his large genus Papilio, containing all known butterfly species, into what we would now call subgenera. The Danai festivi formed one of the "subgenera", containing colorful species, as opposed to the Danai candidi, containing species with bright white wings. Linnaeus wrote: "Danaorum Candidorum nomina a filiabus Danai Aegypti, Festivorum a filiis mutuatus sunt." (English: "The names of the Danai candidi have been derived from the daughters of Danaus, those of the Danai festivi from the sons of Aegyptus.").

Robert Michael Pyle suggested Danaus is a masculinized version of Danaë (Greek Δανάη), Danaus's great-great-granddaughter, to whom Zeus came as a shower of gold, which seemed to him a more appropriate source for the name of this butterfly.[18]

Taxonomy

Monarchs belong in the subfamily Danainae of the family Nymphalidae. Danainae was formerly considered a separately family Danaidae.[19] The three species of monarch butterflies are:

- D. plexippus, described by Linnaeus in 1758, is the species known most commonly as the monarch butterfly of North America. Its range actually extends worldwide, including Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, Spain, and the Pacific Islands.

- D. erippus, the southern monarch, was described by Pieter Cramer in 1775. This species is found in tropical and subtropical latitudes of South America, mainly in Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and southern Peru. The South American monarch and the North American monarch may have been one species at one time. Some researchers believe the southern monarch separated from the monarch's population some two million years ago, at the end of the Pliocene. Sea levels were higher, and the entire Amazonas lowland was a vast expanse of brackish swamp that offered limited butterfly habitat.[20]

- D. cleophile, the Jamaican monarch, described by Jean-Baptiste Godart in 1819, ranges from Jamaica to Hispaniola.[2]

Six subspecies and two color morphs of D. plexippus have been identified:[6]

- D. p. plexippus – nominate subspecies, described by Linnaeus in 1758, is the migratory subspecies known from most of North America.

- D. p. nigrippus (Richard Haensch, 1909) – South America - as forma: Danais [sic] archippus f. nigrippus. Hay-Roe et al. in 2007 identified this taxon as a subspecies[23]

- D. p. megalippe (Jacob Hübner, [1826]) – nonmigratory subspecies, and is found from Florida and Georgia southwards, throughout the Caribbean and Central America to the Amazon River.

- D. p. leucogyne (Arthur G. Butler, 1884) − St. Thomas

- D. p. portoricensis Austin Hobart Clark, 1941 − Puerto Rico

- D. p. tobagi Austin Hobart Clark, 1941 − Tobago

The population level of the white morph in Oahu is nearing 10%. On other Hawaiian islands, the white morph occurs at a relatively low frequency. White monarchs (D. p. p. "form nivosus") have been found throughout the world, including Australia, New Zealand, Indonesia, and the United States.[21] However, some taxonomists disagree on these classifications.[20][23]

Genome

The monarch was the first butterfly to have its genome sequenced.[24]: 12 The 273-million-base pair draft sequence includes a set of 16,866 protein-coding genes. The genome provides researchers insights into migratory behavior, the circadian clock, juvenile hormone pathways, and microRNAs that are differentially expressed between summer and migratory monarchs.[25][26][27] More recently, the genetic basis of monarch migration and warning coloration has been described.[28]

No genetic differentiation exists between the migratory populations of eastern and western North America.[24]: 16 Recent research has identified the specific areas in the genome of the monarch that regulate migration. No genetic difference is seen between a migrating and nonmigrating monarch, but the gene is expressed in migrating monarchs, but not expressed in nonmigrating monarchs.[29]

A 2015 publication identified genes from wasp bracoviruses in the genome of the North American monarch[30] leading to articles about monarch butterflies being genetically modified organisms.[31][32]

Life cycle

Like all Lepidoptera, monarchs undergo complete metamorphosis; their life cycle has four phases: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Monarchs transition from eggs to adults during warm summer temperatures in as little as 25 days, extending to as many as seven weeks during cool spring conditions. During their development, both larvae and their milkweed hosts are vulnerable to weather extremes, predators, parasites, and diseases; commonly fewer than 10% of monarch eggs and caterpillars survive.[24]: 21–22

Egg

The egg is derived from materials ingested as a larva and from the spermatophores received from males during mating.[33] Female monarchs lay eggs singly, most often on the underside of a young leaf of a milkweed plant during the spring and summer.[34] Females secrete a small amount of glue to attach their eggs directly to the plant. They typically lay 300 to 500 eggs over a two- to five-week period.[35]

Eggs are cream colored or light green, ovate to conical in shape, and about 1.2 mm × 0.9 mm (0.047 in × 0.035 in) in size. The eggs weigh less than 0.5 mg (0.0077 gr) each and have raised ridges that form longitudinally from the point to apex to the base. Although each egg is 1⁄1000 the mass of the female, she may lay up to her own mass in eggs. Females lay smaller eggs as they age. Larger females lay larger eggs.[33] The number of eggs laid by a female, which may mate several times, can reach 1,180.[36]

Eggs take three to eight days to develop and hatch into larvae or caterpillars.[24]: 21 The offspring's consumption of milkweed benefits health and helps defend them against predators.[37][38] Monarchs lay eggs along the southern migration route.[39]

Larva

.jpg.webp)

The larva (caterpillar) has five stages (instars), molting at the end of each instar. Instars last about 3 to 5 days, depending on factors such as temperature and food availability.[5][40]

The first-instar caterpillar that emerges from the egg is pale green or grayish-white, shiny, and almost translucent, with a large, black head. It lacks banding coloration or tentacles. The larvae or caterpillar eats its egg case and begins to feed on milkweed with a circular motion, often leaving a characteristic, arc-shaped hole in the leaf. Older first-instar larvae have dark stripes on a greenish background and develop small bumps that later become front tentacles. The first instar is usually between 2 and 6 mm (0.079 and 0.236 in) long.[40]

The second-instar larva develops a characteristic pattern of white, yellow, and black transverse bands. The larva has a yellow triangle on the head and two sets of yellow bands around this central triangle. It is no longer translucent, and is covered in short setae. Pairs of black tentacles begin to grow, a larger pair on the thorax and a smaller pair on the abdomen. The second instar is usually between 6 mm (0.24 in) and 1 cm (0.39 in) long.[40]

The third-instar larva has more distinct bands and the two pairs of tentacles become longer. Legs on the thorax differentiate into a smaller pair near the head and larger pairs further back. Third-instar larvae usually feed using a cutting motion on leaf edges. The third instar is usually between 1 and 1.5 cm (0.39 and 0.59 in) long.[40]

The fourth-instar larva has a different banding pattern. It develops white spots on the prolegs near its back, and is usually between 1.5 and 2.5 cm (0.59 and 0.98 in) long.[40]

The fifth-instar larva has a more complex banding pattern and white dots on the prolegs, with front legs that are small and very close to the head. Fifth-instar larvae often chew a shallow notch in the petiole of the leaf they are eating, which causes the leaf to fall into a vertical position. Its length ranges from 2.5 to 4.5 cm (0.98 to 1.77 in).[5][40]

As the caterpillar completes its growth, it is 4.5 cm (1.8 in) long (large specimens can reach 5 cm (2.0 in)) and 7 to 8 mm (0.28 to 0.31 in) wide, and weighs about 1.5 g (0.053 oz), compared to the first instar, which is 2 to 6 mm (0.079 to 0.236 in) long and 0.5 to 1.5 mm (0.020 to 0.059 in) wide. Fifth-instar larvae greatly increase in size and weight. They then stop feeding and are often found far from milkweed plants as they seek a site for pupating.[40]

In a laboratory setting, the fourth- and fifth-instar stages of the caterpillar showed signs of aggressive behavior with lower food availability. Attacked caterpillars were found to be attacked when it was feeding on milkweed leaves, and the caterpillars attacked when foraging for milkweed.[41] This demonstrates the aggressive behavior of monarch caterpillars due to the availability of milkweed.

Pupa

To prepare for the pupal or chrysalis stage, the caterpillar chooses a safe place for pupation, where it spins a silk pad on a downward-facing horizontal surface. At this point, it turns around and securely latches on with its last pair of hind legs and hangs upside down, in the form of the letter J. After "J-hanging" for about 12–16 hours, it soon straightens out its body and goes into peristalsis some seconds before its skin splits behind its head. It then sheds its skin over a period of a few minutes, revealing a green chrysalis. At first, the chrysalis is long, soft, and somewhat amorphous, but over a few hours, it compacts into its distinct shape – an opaque, pale-green chrysalis with small golden dots near the bottom, and a gold-and-black rim around the dorsal side near the top.[42] At first, its exoskeleton is soft and fragile, but it hardens and becomes more durable within about a day. At this point, it is about 2.5 cm (0.98 in) long and 10–12 mm (0.39–0.47 in) wide, weighing about 1.2 g (0.042 oz). At normal summer temperatures, it matures in 8–15 days (usually 11–12 days). During this pupal stage, the adult butterfly forms inside. A day or so before emerging, the exoskeleton first becomes translucent and the chrysalis more bluish. Finally, within 12 hours or so, it becomes transparent, revealing the black and orange colors of the butterfly inside before it ecloses (emerges).[43][44]

Adult

The adult emerges from its chrysalis after about two weeks of pupation. The emergent adult hangs upside down for several hours while it pumps fluids and air into its wings, which expand, dry, and stiffen. The butterfly then extends and retracts its wings. Once conditions allow, it flies and feeds on a variety of nectar plants. During the breeding season, adults reach sexual maturity in 4–5 days. However, the migrating generation does not reach maturity until overwintering is complete.[45]

The adult's wingspan ranges from 8.9 to 10.2 centimetres (3.5 to 4.0 in).[10] The upper sides of the wings are tawny orange, the veins and margins are black, and two series of small white spots occur in the margins. Monarch forewings also have a few orange spots near their tips. Wing undersides are similar, but the tips of forewings and hindwings are yellow brown instead of tawny orange and the white spots are larger.[46] The shape and color of the wings change at the beginning of the migration and appear redder and more elongated than later migrants.[47] Wings size and shape differ between migratory and nonmigratory monarchs. Monarchs from eastern North America have larger and more angular forewings than those in the western population.[24]

In eastern North American populations, overall wing size in the physical dimensions of wings varies. Males tend to have larger wings than females, and are typically heavier than females. Both males and females have similar thoracic dimensions. Female monarchs tended to have thicker wings, which is thought to convey greater tensile strength and reduce the likelihood of being damaged during migration. Additionally, females had lower wing loading than males, which would mean females require less energy to fly.[48]

Adults are sexually dimorphic. Males are slightly larger than females and have a black spot on a vein on each hindwing. The spots contain scales that produce pheromones that many Lepidoptera use during courtship. Females are often darker than males and have wider veins on their wings. The ends of the abdomens of males and females differ in shape.[46][49][24][50][51][52]

The adult's thorax has six legs, but as in all of the Nymphalidae, the forelegs are small and held against the body. The butterfly uses only its middle and hindlegs when walking and clinging.[53]

Adults typically live for 2–5 weeks during their breeding season.[24]: 22–23 Larvae growing in high densities are smaller, have lower survival, and weigh less as adults compared with those growing in lower densities.[54]

Vision

Physiological experiments suggest that monarch butterflies view the world through a tetrachromatic system.[55] Like humans, their retina contain three types of opsin proteins, expressed in distinct photoreceptor cells, each of which absorbs light at a different wavelength. Unlike humans, one of those types of photoreceptor cells corresponds to a wavelength in the ultraviolet range; the other two correspond to blue and green.[56]

In addition to these three photoreceptors cells in the main retina, monarch butterfly eyes contain orange filtering pigments that filter the light reaching some green-absorbing opsins, thereby making a fourth photoreceptor cell sensitive to longer-wavelength light.[55] The combination of filtered and unfiltered green opsins permits the butterflies to distinguish yellow from orange colors.[55] The ultraviolet opsin protein has also been detected in the dorsal rim region of monarch eyes. One study suggests that this allows the butterflies the ability to detect ultraviolet polarized skylight to orient themselves with the sun for their long migratory flight.[57]

These butterflies are capable of distinguishing colors based on their wavelength only, and not based on intensity; this phenomenon is termed "true color vision". This is important for many butterfly behaviors, including seeking nectar for nourishment, choosing a mate, and finding milkweed on which to lay eggs. One study found that floral color is more easily recognized at a distance by butterflies searching for nectar than floral shape. This may be because flowers have highly contrasting colors to the green background of a vegetative landscape.[58] On the other hand, leaf shape is important for oviposition so that the butterflies can ensure their eggs are being laid on milkweed.

Beyond the perception of color, the ability to remember certain colors is essential in the life of monarch butterflies. These insects can easily learn to associate color, and to a lesser extent, shape, with sugary food rewards. When searching for nectar, color is the first cue that draws the insect's attention toward a potential food source, and shape is a secondary characteristic that promotes the process. When searching for a place to lay its eggs, the roles of color and shape are switched. Also, a difference may exist between male and female butterflies from other species in terms of the ability to learn certain colors; however, no differences are noted between the sexes for monarch butterflies.[58]

Courtship and mating

Monarch courtship occurs in two phases. During the aerial phase, a male pursues and often forces a female to the ground. During the ground phase, the butterflies copulate and remain attached for about 30 to 60 minutes.[59] Only 30% of mating attempts end in copulation, suggesting that females may be able to avoid mating, though some have more success than others.[60][61] During copulation, a male transfers his spermatophore to a female. Along with sperm, the spermatophore provides a female with nutrition, which aids her in laying eggs. An increase in spermatophore size increases the fecundity of female monarchs. Males that produce larger spermatophores also fertilize more females' eggs.[62]

Females and males typically mate more than once. Females that mate several times lay more eggs.[63] Mating for the overwintering populations occurs in the spring, prior to dispersion. Mating is less dependent on pheromones than in other species in its genus.[64] Male search and capture strategies may influence copulatory success, and human-induced changes to the habitat can influence monarch mating activity at overwintering sites.[65]

Distribution and habitat

The range of the western and eastern populations of D. p. plexippus expands and contracts depending upon the season. The range differs between breeding areas, migration routes, and winter roosts.[24]: 18 However, no genetic differences between the western and eastern monarch populations exist;[29] reproductive isolation has not led to subspeciation of these populations, as it has elsewhere within the species' range.[24]: 19

In the Americas, the monarch ranges from southern Canada through northern South America.[5] It is also found in Bermuda, Cook Islands,[66] Hawaii,[67][68] Cuba,[69] and other Caribbean islands[24]: 18 the Solomons, New Caledonia, New Zealand,[70] Papua New Guinea,[71] Australia, the Azores, the Canary Islands, Madeira, continental Portugal, Gibraltar,[72] the Philippines, and Morocco.[73] It appears in the UK in some years as an accidental migrant.[74]

Overwintering populations of D. p. plexippus are found in Mexico, California, along the Gulf Coast of the United States, year-round in Florida, and in Arizona where the habitat has the specific conditions necessary for their survival.[75][76] On the East Coast of the United States, they have overwintered as far north as Lago Mar, Virginia Beach, Virginia.[77] Their wintering habitat typically provides access to streams, plenty of sunlight (enabling body temperatures that allow flight), and appropriate roosting vegetation, and is relatively free of predators.

Overwintering, roosting butterflies have been seen on basswoods, elms, sumacs, locusts, oaks, osage-oranges, mulberries, pecans, willows, cottonwoods, and mesquites.[78] While breeding, monarch habitats can be found in agricultural fields, pasture land, prairie remnants, urban and suburban residential areas, gardens, trees, and roadsides – anywhere where there is access to larval host plants.[79]

Larval host plants

The host plants used by the monarch caterpillar include:

- Asclepias angustifolia – Arizona milkweed[80]

- Asclepias albicans – whitestem milkweed

- Asclepias asperula – antelope horns milkweed[80]

- Asclepias californica – California milkweed[80]

- Asclepias cordifolia – heartleaf milkweed[80]

- Asclepias curassavica

- Asclepias eriocarpa – woolly pod milkweed[80]

- Asclepias erosa – desert milkweed[80]

- Asclepias exaltata – poke milkweed[80]

- Asclepias fascicularis – Mexican whorled milkweed[80]

- Asclepias humistrata – sandhill/pinewoods milkweed[80]

- Asclepias incarnata – swamp milkweed[81][82][83][84]

- Asclepias linaria – pineneedle milkweed

- Asclepias nivea – Caribbean milkweed[85]

- Asclepias oenotheroide – zizotes milkweed[80]

- Asclepias perennis – aquatic milkweed[80]

- Asclepias speciosa – showy milkweed[80][86][87][88][89]

- Asclepias subulata – rush milkweed[80]

- Asclepias syriaca – common milkweed[90]

- Asclepias tuberosa – butterfly weed[80]

- Asclepias variegata – white milkweed[80]

- Asclepias verticillata – whorled milkweed[80]

- Asclepias vestita – woolly milkweed[80]

- Asclepias viridis – green antelopehorn milkweed[80][91][92][93][94]

- Calotropis gigantea – crown flower[95]

- Calotropis procera

- Cynanchum laeve – sand vine milkweed[96]

- Sarcostemma clausa – white vine[67][97]

Asclepias curassavica, or tropical milkweed, is often planted as an ornamental in butterfly gardens. Year-round plantings in the USA are controversial and criticised, as they may be the cause of new overwintering sites along the U.S. Gulf Coast, leading to year-round breeding of monarchs.[98] This is thought to adversely affect migration patterns, and to cause a dramatic buildup of the dangerous parasite, Ophryocystis elektroscirrha.[99] New research also has shown that monarch larvae reared on tropical milkweed show reduced migratory development (reproductive diapause), and when migratory adults are exposed to tropical milkweed, it stimulates reproductive tissue growth.[100]

Adult food sources

Although larvae eat only milkweed, adult monarchs feed on the nectar of many plants, including:[101]

- Apocynum cannabinum – Indian hemp

- Asclepias spp. – milkweed

- Symphyotrichum sp. – New World aster

- Cirsium sp. – thistle

- Daucus carota – wild carrot

- Dipsacus sylvestris – teasel

- Echinacea sp. – coneflower

- Erigeron canadensis – horseweed

- Eupatorium maculatum – spotted Joe-Pye weed

- Eupatorium perfoliatum – common boneset

- Hesperis matronalis – dame's rocket

- Liatris sp. – blazing stars

- Medicago sativa – alfalfa

- Solidago sp. – goldenrod

- Syringa vulgaris – lilac

- Trifolium pratense – red clover

- Vernonia altissima – tall ironweed[76]

Monarchs obtain moisture and minerals from damp soil and wet gravel, a behavior known as mud-puddling. The monarch has also been noticed puddling at an oil stain on pavement.[76]

Flight and migration

_on_Oyamel_fir_(Abies_religiosa)_Piedra_Herrada.jpg.webp)

Piedra Herrada, Mexico

In North America, monarchs migrate both north and south on an annual basis, in a long-distance journey that is fraught with risks.[5] This is a multi-generational migration, with individual monarchs only making part of the full journey.[102] The population east of the Rocky Mountains attempts to migrate to the sanctuaries of the Mariposa Monarca Biosphere Reserve in the Mexican state of Michoacán and parts of Florida. The western population tries to reach overwintering destinations in various coastal sites in central and southern California. The overwintered population of those east of the Rockies may reach as far north as Texas and Oklahoma during the spring migration. The second, third, and fourth generations return to their northern locations in the United States and Canada in the spring.[103]

Captive-raised monarchs appear capable of migrating to overwintering sites in Mexico,[104] though they have a much lower migratory success rate than do wild monarchs (see section on captive-rearing below).[105] Monarch overwintering sites have been discovered recently in Arizona.[106] Monarchs from the eastern US generally migrate longer distances than monarchs from the western US.[107]

Since the 1800s, monarchs have spread throughout the world, and there are now many non-migratory populations globally.[108]

Flight speeds of adults are around 9 km/h (6 mph).[109]

Interactions with predators

In both caterpillar and butterfly form, monarchs are aposematic, warding off predators with a bright display of contrasting colors to warn potential predators of their undesirable taste and poisonous characteristics. One monarch researcher emphasizes that predation on eggs, larvae or adults is natural, since monarchs are part of the food chain, thus people should not take steps to kill predators of monarchs.[110]

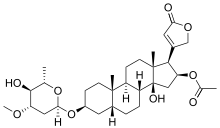

Larvae feed exclusively on milkweed and consume protective cardiac glycosides. Toxin levels in Asclepias species vary. Not all monarchs are unpalatable, but exhibit Batesian or automimics. Cardiac glycosides levels are higher in the abdomen and wings. Some predators can differentiate between these parts and consume the most palatable ones.[111]

Butterfly weed (A. tuberosa) lacks significant amounts of cardiac glycosides (cardenolides), but instead contains other types of toxic glycosides, including pregnanes.[112][113][114] This difference may reduce the toxicity of monarchs whose larvae feed on that milkweed species, as a naturalist and others have reported that monarch caterpillars do not favor the plant.[115] Some other milkweeds have similar characteristics.[116]

Types of predators

While monarchs have a wide range of natural predators, none of these is suspected of causing harm to the overall population, or are the cause of the long-term declines in winter colony sizes.

Several species of birds have acquired methods that allow them to ingest monarchs without experiencing the ill effects associated with the cardiac glycosides (cardenolides). The black-backed oriole is able to eat the monarch through an exaptation of its feeding behavior that gives it the ability to identify cardenolides by taste and reject them.[117] The black-headed grosbeak, though, has developed an insensitivity to secondary plant poisons that allows it to ingest monarchs without vomiting.[118] As a result, these orioles and grosbeaks periodically have high levels of cardenolides in their bodies, and they are forced to go on periods of reduced monarch consumption. This cycle effectively reduces potential predation of monarchs by 50% and indicates that monarch aposematism has a legitimate purpose.[117] The black-headed grosbeak has also evolved resistance mutations in the molecular target of the heart poisons, the sodium pump. The specific mutations that evolved in one of the grosbeak's four copies of the sodium pump gene are the same as those found in other milkweed butterflies like the common crow that also evolved to resist cardiac glycosides.[119] Other bird predators include brown thrashers, grackles, robins, cardinals, sparrows, scrub jays, and pinyon jays.[111]

The monarch's white morph appeared in Oahu after the 1965–1966 introduction of two bulbul bird species, Pycnonotus cafer and Pycnonotus jocosus. These are now the most common avian insectivores in Hawaii, and probably the only ones that eat insects as large as monarchs. Although Hawaiian monarchs have low cardiac glycoside levels, the birds may also be tolerant of that toxin. The two species hunt the larvae and some pupae from the branches and undersides of leaves in milkweed bushes. The bulbuls also eat resting and ovipositing adults, but rarely flying ones. Because of its color, the white morph has a higher survival rate than the orange one. This is either because of apostatic selection (i.e., the birds have learned the orange monarchs can be eaten), because of camouflage (the white morph matches the white pubescence of milkweed or the patches of light shining through foliage), or because the white morph does not fit the bird's search image of a typical monarch, so is thus avoided.[120]

Some mice, particularly the black-eared mouse (Peromyscus melanotis), are, like all rodents, able to tolerate large doses of cardenolides and are able to eat monarchs.[121] Overwintering adults become less toxic over time making them more vulnerable to predators. In Mexico, about 14% of the overwintering monarchs are eaten by birds and mice and black-eared mice can eat up to 40 monarchs per night.[75][121]

In North America, eggs and first-instar larvae of the monarch are eaten by larvae and adults of the introduced Asian lady beetle (Harmonia axyridis).[122] The Chinese mantis (Tenodera sinensis) will consume the larvae once the gut is removed thus avoiding cardenolides.[123] Predatory wasps commonly consume larvae,[124] though large larvae may avoid wasp predation by dropping from the plant or by jerking their bodies.[125]

Aposematism

Monarchs are toxic and foul-tasting because of the presence of cardenolides in their bodies, which the caterpillars ingest as they feed on milkweed.[64] Monarchs and other cardenolide-resistant insects rely on a resistant form of the Na+/ K+-ATPase enzyme to tolerate significantly higher concentrations of cardenolides than nonresistant species.[126] By ingesting a large amount of plants in the genus Asclepias, primarily milkweed, monarch caterpillars are able to sequester cardiac glycosides, or more specifically cardenolides, which are steroids that act in heart-arresting ways similar to digitalis.[127] It has been found that monarchs are able to sequester cardenolides most effectively from plants of intermediate cardenolide content rather than those of high or low content.[128] Three mutations that evolved in the monarch's Na+/ K+-ATPase were found to be sufficient together to confer resistance to dietary cardiac glycosides.[126] This was tested by swapping these mutations into the same gene in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster using CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. These fruit flies-turned monarch flies[129] were completely resistant to dietary ouabain, a cardiac glycoside found in Apocynaceae, and even sequestered some through metamorphosis, like the monarch.[126]

Different species of milkweed have different effects on growth, virulence, and transmission of parasites.[130] One species, Asclepias curassavica, appears to reduce the symptoms of Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE) infection. The two possible explanations for this include that it promotes overall monarch health to boost the monarch's immune system or that chemicals from the plant have a direct negative effect on the OE parasites.[130] A. curassavica does not cure or prevent the infection with OE; it merely allows infected monarchs to live longer, and this would allow infected monarchs to spread the OE spores for longer periods. For the average home butterfly garden, this scenario only adds more OE to the local population.[131]

After the caterpillar becomes a butterfly, the toxins shift to different parts of the body. Since many birds attack the wings of the butterfly, having three times the cardiac glycosides in the wings leaves predators with a very foul taste and may prevent them from ever ingesting the body of the butterfly.[127] To combat predators that remove the wings only to ingest the abdomen, monarchs keep the most potent cardiac glycosides in their abdomens.[132]

Mimicry

Monarchs share the defense of noxious taste with the similar-appearing viceroy butterfly in what is perhaps one of the most well-known examples of mimicry. Though long purported to be an example of Batesian mimicry, the viceroy is actually reportedly more unpalatable than the monarch, making this a case of Müllerian mimicry.[133]

Human interaction

The monarch is the state insect of Alabama,[134] Idaho,[135] Illinois,[136] Minnesota,[137] Texas,[138] Vermont,[139] and West Virginia.[140] Legislation was introduced to make it the national insect of the United States,[141] but this failed in 1989[142] and again in 1991.[143]

Homeowners are increasingly establishing butterfly gardens; monarchs can be attracted by cultivating a butterfly garden with specific milkweed species and nectar plants. Efforts are underway to establish these monarch waystations. [144]

An IMAX film, Flight of the Butterflies, describes the story of the Urquharts, Brugger, and Trail to document the then-unknown monarch migration to Mexican overwintering areas.[145]

Sanctuaries and reserves have been created at overwintering locations in Mexico and California to limit habitat destruction. These sites can generate significant tourism revenue.[146] However, with less tourism, monarch butterflies will have a higher survival rate because they show more protein content and a higher value of immune response and oxidative defense.[147]

Organizations and individuals participate in tagging programs. Tagging information is used to study migration patterns.[148]

The 2012 novel by Barbara Kingsolver, Flight Behavior, deals with the fictional appearance of a large population in the Appalachians.[149]

Captive rearing

Humans interact with monarchs when rearing them in captivity, which has become increasingly popular. However, risks occur in this controversial activity. On one hand, captive rearing has many positive aspects. Monarchs are bred in schools and used for butterfly releases at hospices, memorial events, and weddings.[150] Memorial services for the September 11 attacks include the release of captive-bred monarchs.[151][152][153] Monarchs are used in schools and nature centers for educational purposes.[154] Many homeowners raise monarchs in captivity as a hobby and for educational purposes.[155]

On the other hand, this practice becomes problematic when monarchs are "mass-reared". Stories in the Huffington Post in 2015 and Discover magazine in 2016 have summarized the controversy around this issue.[156][157]

The frequent media reports of monarch declines have encouraged many homeowners to attempt to rear as many monarchs as possible in their homes and then release them to the wild in an effort to "boost the monarch population". Some individuals, such as one in Linn County, Iowa, have reared thousands of monarchs at the same time.[158]

Some monarch scientists do not condone the practice of rearing "large" numbers of monarchs in captivity for release into the wild because of the risks of genetic issues and disease spread.[159] One of the biggest concerns of mass rearing is the potential for spreading the monarch parasite, Ophryocystis elektroscirrha, into the wild. This parasite can rapidly build up in captive monarchs, especially if they are housed together. The spores of the parasite also can quickly contaminate all housing equipment, so that all subsequent monarchs reared in the same containers then become infected. One researcher stated that rearing more than 100 monarchs constitutes "mass rearing" and should not be done.[160]

In addition to the disease risks, researchers believe these captive-reared monarchs are not as fit as wild ones, owing to the unnatural conditions in which they are raised. Homeowners often raise monarchs in plastic or glass containers in their kitchens, basements, porches, etc., and under artificial lighting and controlled temperatures. Such conditions would not mimic what the monarchs are used to in the wild, and may result in adults that are unsuited for the realities of their wild existence. In support of this, a recent study by a citizen scientist found that captive-reared monarchs have a lower migration success rate than wild monarchs do.[105]

A 2019 study shed light on the fitness of captive-reared monarchs, by testing reared and wild monarchs on a tethered flight apparatus that assessed navigational ability.[161] In that study, monarchs that were reared to adulthood in artificial conditions showed a reduction in navigational ability. This happened even with monarchs that were brought into captivity from the wild for a few days. A few captive-reared monarchs did show proper navigation. This study revealed the fragility of monarch development; if the conditions are not suitable, their ability to properly migrate could be impaired. The same study also examined the genetics of a collection of reared monarchs purchased from a butterfly breeder, and found they were dramatically different from wild monarchs, so much so that the lead author described them as "franken-monarchs".[162]

An unpublished study in 2019 compared behavior of captive-reared versus wild monarch larvae.[163] The study showed that reared larvae exhibited more defensive behavior than wild larvae. The reason for this is unknown, but it could relate to the fact that reared larvae are frequently handled and/or disturbed.

Threats

In February 2015, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reported a study that showed that nearly a billion monarchs had vanished from the butterfly's overwintering sites since 1990. The agency attributed the monarch's decline in part to a loss of milkweed caused by herbicides that farmers and homeowners had used.[164]

Western monarch populations

Based on a 2014 20-year comparison, the overwintering numbers west of the Rocky Mountains have dropped more than 50% since 1997 and the overwintering numbers east of the Rockies have declined by more than 90% since 1995. According to the Xerces Society, the monarch population in California decreased 86% in 2018, going from millions of butterflies to tens of thousands of butterflies.[165]

The society's annual 2020–2021 winter count showed a significant decline in the California population. One Pacific Grove site did not have a single monarch butterfly. A primary explanation for this was the destruction of the butterfly's milkweed habitats.[24][166] This particular population is believed to comprise less than 2000 individuals, as of 2022.[167]

Eastern and midwestern monarch populations

A 2016 publication attributed the previous decade's 90% decline in overwintering numbers of the eastern monarch population to the loss of breeding habitat and milkweed. The publication's authors stated that an 11%–57% probability existed that this population will go almost extinct over the next 20 years.[168]

Chip Taylor, the director of Monarch Watch at the University of Kansas, has stated that the Midwest milkweed habitat "is virtually gone" with 120–150 million acres lost.[169][170] To help fight this problem, Monarch Watch encourages the planting of "Monarch Waystations".[155]

Habitat loss due to herbicide use and genetically modified crops

Declines in milkweed abundance and monarch populations between 1999 and 2010 are correlated with the adoption of herbicide-tolerant genetically modified (GM) corn and soybeans, which now constitute 89% and 94% of these crops, respectively, in the U.S.[168] GM corn and soybeans are resistant to the effect of the herbicide glyphosate. Some conservationists attribute the disappearance of milkweed to agricultural practices in the Midwest, where GM seeds are bred to resist herbicides that farmers use to kill unwanted plants that grow near their rows of food crops.[171][172]

In 2015, the Natural Resources Defense Council filed a suit against the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The Council argued that the agency ignored warnings about the dangers of glyphosate usage for monarchs.[173] However, a 2018 study has suggested that the decline in milkweed predates the arrival of GM crops.[174]

Losses during migration

Eastern and midwestern monarchs are apparently experiencing problems reaching Mexico. A number of monarch researchers have cited recent evidence obtained from long-term citizen science data that show that the number of breeding (adult) monarchs has not declined in the last two decades.[175][176][177]

The lack of long-term declines in the numbers of breeding and migratory monarchs, yet the clear declines in overwintering numbers, suggests a growing disconnect exists between these life stages. One researcher has suggested that mortality from car strikes constitutes an increasing threat to migrating monarchs.[178] A study of road mortality in northern Mexico, published in 2019, showed very high mortality from just two "hotspots" each year, amounting to 200,000 monarchs killed.[179]

Loss of overwintering habitat

The area of Mexican forest to which eastern and midwestern monarchs migrate reached its lowest level in two decades in 2013. The decline was expected to increase during the 2013–2014 season. Mexican environmental authorities continue to monitor illegal logging of the oyamel trees. The oyamel is a major species of evergreen on which the overwintering butterflies spend a significant time during their winter diapause, or suspended development.[180]

A 2014 study acknowledged that while "the protection of overwintering habitat has no doubt gone a long way towards conserving monarchs that breed throughout eastern North America", their research indicates that habitat loss on breeding grounds in the United States is the main cause of both recent and projected population declines.[181]

Western monarch populations have rebounded slightly since 2014 with the Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count [182] tallying 335,479 monarchs in 2022. The population still has much to go for a full recovery.

Parasites

Parasites include the tachinid flies Sturmia convergens[183] and Lespesia archippivora. Lesperia-parasitized butterfly larvae suspend, but die prior to pupation. The fly's maggot lowers itself to the ground, forms a brown puparium and then emerges as an adult.[184]

Pteromalid wasps, specifically Pteromalus cassotis, parasitize monarch pupae.[185] These wasps lay their eggs in the pupae while the chrysalis is still soft. Up to 400 adults emerge from the chrysalis after 14–20 days,[185] killing the monarch.

The bacterium Micrococcus flacidifex danai also infects larvae. Just before pupation, the larvae migrate to a horizontal surface and die a few hours later, attached only by one pair of prolegs, with the thorax and abdomen hanging limp. The body turns black shortly thereafter. The bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa has no invasive powers, but causes secondary infections in weakened insects. It is a common cause of death in laboratory-reared insects.[184]

Ophryocystis elektroscirrha is another parasite of the monarch. It infects the subcutaneous tissues and propagates by spores formed during the pupal stage. The spores are found over all of the body of infected butterflies, with the greatest number on the abdomen. These spores are passed, from female to caterpillar, when spores rub off during egg laying and are then ingested by caterpillars. Severely infected individuals are weak, unable to expand their wings, or unable to eclose, and have shortened lifespans, but parasite levels vary in populations. This is not the case in laboratory rearing, where after a few generations, all individuals can be infected.[186]

Infection with O. elektroscirrha creates an effect known as culling, whereby migrating monarchs that are infected are less likely to complete the migration. This results in overwintering populations with lower parasite loads.[187] Owners of commercial butterfly-breeding operations claim that they take steps to control this parasite in their practices,[188] although this claim is doubted by many scientists who study monarchs.[189]

Confusion of host plants

The black swallow-wort (Cynanchum louiseae) and pale swallow-wort (Cynanchum rossicum) plants are problematic for monarchs in North America. Monarchs lay their eggs on these relatives of native vining milkweed (Cynanchum laeve) because they produce stimuli similar to milkweed. Once the eggs hatch, the caterpillars are poisoned by the toxicity of this invasive plant from Europe.[190]

Climate

Climate variations during the fall and summer affect butterfly reproduction. Rainfall and freezing temperatures affect milkweed growth. Omar Vidal, director general of WWF-Mexico, said, "The monarch's lifecycle depends on the climatic conditions in the places where they breed. Eggs, larvae, and pupae develop more quickly in milder conditions. Temperatures above 35 °C (95 °F) can be lethal for larvae, and eggs dry out in hot, arid conditions, causing a drastic decrease in hatch rate."[191] If a monarch's body temperatures is below 30 °C (86 °F), a monarch cannot fly. To warm up, they sit in the sun or rapidly shiver their wings to warm themselves.[192]

Climate change may dramatically affect the monarch migration. A study from 2015 examined the impact of warming temperatures on the breeding range of the monarch, and showed that in the next 50 years the monarch host plant will expand its range further north into Canada, and that the monarchs will follow this.[193] While this will expand the breeding locations of the monarch, it will also have the effect of increasing the distance that monarchs must travel to reach their overwintering destination in Mexico, which could result in greater mortality during the migration.[194]

Milkweeds grown at increased temperatures have been shown to contain higher cardenolide concentrations, making the leaves too toxic for the monarch caterpillars. However, these increased concentrations are likely in response to increased insect herbivory, which is also caused by the increased temperatures. Whether increased temperatures make milkweed too toxic for monarch caterpillars when other factors are not present is unknown.[195] Additionally, milkweed grown at carbon dioxide levels of 760 parts per million was found to produce a different mix of the toxic cardenolides, one of which was less effective against monarch parasites.[196]

Conservation status

On July 20, 2022, the International Union for Conservation of Nature added the migratory monarch butterfly (the subspecies common in North America) to its red list of endangered species.[197][2]

The monarch butterfly is not currently listed under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora or protected specifically under U.S. domestic laws.[198]

On August 14, 2014, the Center for Biological Diversity and the Center for Food Safety filed a legal petition requesting Endangered Species Act protection for the monarch and its habitat,[24] based largely on the long-term trends observed at overwintering sites. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) initiated a status review of the monarch butterfly under the Endangered Species Act with a due date for information submission of March 3, 2015, later extended to 2020. On December 15, 2020, the FWS ruled that adding the butterfly to the list of threatened and endangered species was "warranted-but-precluded" because it needed to devote its resources to 161 higher-priority species.[199]

The number of monarchs overwintering in Mexico has shown a long-term downward trend. Since 1995, coverage numbers have been as high as 18 hectares (44 acres) during the winter of 1996–1997, but on average about 6 hectares (15 acres). Coverage declined to its lowest point to date (0.67 hectares (1.66 acres)) during the winter of 2013–2014, but rebounded to 4.01 hectares (10 acres) in 2015–2016. The average population of monarchs in 2016 was estimated at 200 million. Historically, on average there are 300 million monarchs. The 2016 increase was attributed to favorable breeding conditions in the summer of 2015. However, coverage declined by 27% to 2.91 hectares (7.19 acres) during the winter of 2016–2017. Some believe this was because of a storm that had occurred during March 2016 in the monarchs' previous overwintering season,[200][201][202] though this seems unlikely since most current research shows that the overwintering colony sizes do not predict the size of the next summer breeding population.[203]

In Ontario, Canada, the monarch butterfly is listed as a species of special concern.[204] In fall 2016, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada proposed that the monarch be listed as endangered in Canada, as opposed to its current listing as a "species of concern" in that country. This move, once enacted, would protect critical monarch habitat in Canada, such as major fall accumulation areas in southern Ontario, but it would also have implications for citizen scientists who work with monarchs, and for classroom activities. If the monarch were federally protected in Canada, these activities could be limited, or require federal permits.[205]

In Nova Scotia, the monarch is listed as endangered at the provincial level, as of 2017. This decision (as well as the Ontario decision) apparently is based on a presumption that the overwintering colony declines in Mexico create declines in the breeding range in Canada.[206] Two recent studies have been conducted examining long-term trends in monarch abundance in Canada, using either butterfly atlas records[207] or citizen science butterfly surveys,[208] and neither shows evidence of a population decline in Canada.

Conservation efforts

Although numbers of breeding monarchs in eastern North America have apparently not decreased, reports of declining numbers of overwintering butterflies have inspired efforts to conserve the species.[175][176][177]

Federal actions

On June 20, 2014, President Barack Obama issued a presidential memorandum entitled "Creating a Federal Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey Bees and Other Pollinators". The memorandum established a Pollinator Health Task Force, to be co-chaired by the Secretary of Agriculture and the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, and stated:

The number of migrating Monarch butterflies sank to the lowest recorded population level in 2013–14, and there is an imminent risk of failed migration.[209]

In May 2015, the Pollinator Health Task Force issued a "National Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey Bees and Other Pollinators". The strategy laid out federal actions to achieve three goals, two of which were:

- Monarch Butterflies: Increase the Eastern population of the monarch butterfly to 225 million butterflies occupying an area of approximately 15 acres (6 hectares) in the overwintering grounds in Mexico, through domestic/international actions and public-private partnerships, by 2020.

- Pollinator Habitat Acreage: Restore or enhance 7 million acres of land for pollinators over the next 5 years through Federal actions and public/private partnerships.[210]

Many of the priority projects that the national strategy identified focused on the I-35 corridor, which extends for 1,500 miles (2,400 km) from Texas to Minnesota. The area through which that highway travels provides spring and summer breeding habitats in the United States' key monarch migration corridor.[210]

The U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) publishes sets of landscape performance requirements in its P100 documents, which mandate standards for the GSA's Public Buildings Service. Beginning in March 2015, those performance requirements and their updates have included four primary aspects for planting designs that are intended to provide adequate on-site foraging opportunities for targeted pollinators. The targeted pollinators include bees, butterflies, and other beneficial insects.[211][212][213]

On December 4, 2015, President Obama signed into law the Fixing America's Surface Transportation (FAST) Act (Pub. L. 114-94).[214] The FAST Act placed a new emphasis on efforts to support pollinators. To accomplish this, the FAST Act amended Title 23 (Highways) of the United States Code. The amendment directed the United States Secretary of Transportation, when carrying out programs under that title in conjunction with willing states, to:

- encourage integrated vegetation management practices on roadsides and other transportation rights-of-way, including reduced mowing; and

- encourage the development of habitat and forage for Monarch butterflies, other native pollinators, and honey bees through plantings of native forbs and grasses, including noninvasive, native milkweed species that can serve as migratory way stations for butterflies and facilitate migrations of other pollinators.[215]

The FAST Act also stated that activities to establish and improve pollinator habitat, forage, and migratory way stations may be eligible for Federal funding if related to transportation projects funded under Title 23.[215]

The United States Department of Agriculture's Farm Service Agency helps increase U.S. populations of monarch butterfly and other pollinators through its Conservation Reserve Program's State Acres for Wildlife Enhancement (SAFE) Initiative. The SAFE Initiative provides an annual rental payment to farmers who agree to remove environmentally sensitive land from agricultural production and who plant species that will improve environmental health and quality. Among other things, the initiative encourages landowners to establish wetlands, grasses, and trees to create habitats for species that the FWS has designated to be threatened or endangered.[216][217][218][219]

Other actions

Agriculture companies and other organizations are being asked to set aside areas that remain unsprayed to allow monarchs to breed. In addition, national and local initiatives are underway to help establish and maintain pollinator habitats along corridors containing power lines and roadways. The Federal Highway Administration, state governments, and local jurisdictions are encouraging highway departments and others to limit their use of herbicides, to reduce mowing, to help milkweed to grow and to encourage monarchs to reproduce within their right-of-ways.[172][220]

National Cooperative Highway Research Program report

In 2020, the National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCRHP) of the Transportation Research Board issued a 208-page report that described a project that had examined the potential for roadway corridors to provide habitat for monarch butterflies. A part of the project developed tools for roadside managers to optimize potential habitat for monarch butterflies in their road rights-of-way.[221][222]

Such efforts are controversial because the risk of butterfly mortality near roads is high. Several studies have shown that motor vehicles kill millions of monarchs and other butterflies every year.[178] Also, some evidence indicates that monarch larvae living near roads experience physiological stress conditions, as evidenced by elevations in their heart rate.[223]

The NCRHP report acknowledged that, among other hazards, roads present a danger of traffic collisions for monarchs, stating that these effects appear to be more concentrated in particular funnel areas during migration.[224] Nevertheless, the report concluded:

In summary, threats along roadway corridors exist for monarchs and other pollinators, but in the context of the amount of habitat needed for recovery of sustainable populations, roadsides are of vital importance.[224]

Butterfly gardening

While scientific studies on the subject have been reported, the practice of butterfly gardening and creating "monarch waystations" is commonly thought to increase the populations of butterflies.[225][226][227][228][229][230][231] Efforts to restore falling monarch populations by establishing butterfly gardens and monarch waystations require particular attention to the butterfly's food preferences and population cycles, as well to the conditions needed to propagate and maintain milkweed.[232][233]

For example, in the Washington, DC, area and elsewhere in the northeastern United States, monarchs prefer to reproduce on common milkweed (A. syriaca), especially when its foliage is soft and fresh. Because monarch reproduction in that area peaks in late summer when milkweed foliage is old and tough, A. syriaca needs to be mowed or cut back in June through August to assure that it will be regrowing rapidly when monarch reproduction reaches its peak. Similar conditions exist for showy milkweed (A. speciosa) in Michigan and for green antelopehorn milkweed (A. viridis), where it grows in the Southern Great Plains and the Western United States.[80][234][235][236][237][238] In addition, the seeds of A. syriaca and some other milkweeds need periods of cold treatment (cold stratification) before they will germinate.[239][240][241][242][243][244]

To protect seeds from washing away during heavy rains and from seed–eating birds, one can cover the seeds with a light fabric or with an 0.5-inch (13 mm) layer of straw mulch.[245][246] However, mulch acts as an insulator. Thicker layers of mulch can prevent seeds from germinating if they prevent soil temperatures from rising enough when winter ends. Further, few seedlings can push through a thick layer of mulch.[247]

Although monarch caterpillars will feed on butterfly weed (A. tuberosa) in butterfly gardens, the plant has rough leaves and is typically not a heavily used host plant for the species.[248] The plant's low levels of cardenolides may also make the plant unattractive to egg-laying monarchs.[115] While A. tuberosa's colorful flowers provide nectar for many adult butterflies, the plant may be less suitable for use in butterfly gardens and monarch waystations than are other milkweed species.[248]

Breeding monarchs prefer to lay eggs on swamp milkweed (A. incarnata).[249][250][251][252][253][254] However, A. incarnata is an early successional plant that usually grows at the margins of wetlands and in seasonally flooded areas. The plant is slow to spread via seeds, does not spread by runners and tends to disappear as vegetative densities increase and habitats dry out.[254][255] Although A. incarnata plants can survive for up to 20 years, most live only two-five years in gardens. The species is not shade-tolerant and is not a good vegetative competitor.[255]

See also

References

- Walker, A.; Thogmartin, W. E.; Oberhauser, K. S.; Pelton, E. M.; Pleasants, J. M. (2022). "Danaus plexippus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T159971A806727. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T159971A806727.en. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- "Migratory Monarch Butterfly". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- Committee on Generic Nomenclature, Royal Entomological Society of London (2007) [1934]. The Generic Names of British Insects. Royal Entomological Society of London Committee on Generic Nomenclature, Committee on Generic Nomenclature. British Museum (Natural History). Dept. of Entomology. p. 20.

- Scudder, Samuel H.; William M. Davis; Charles W. Woodworth; Leland O. Howard; Charles V. Riley; Samuel W. Williston (1989). The butterflies of the eastern United States and Canada with special reference to New England. The author. p. 721. ISBN 978-0-665-26322-4.

- Agrawal, Anurag (March 7, 2017). Monarchs and Milkweed: A Migrating Butterfly, a Poisonous Plant, and Their Remarkable Story of Coevolution. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400884766.

- Savela, Markku (February 25, 2019). "Danaus plexippus (Linnaeus, 1758)". Lepidoptera and Some Other Life Forms. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- "Conserving Monarch Butterflies and their Habitats". USDA. 2015.

- Jones, Patricia L.; Agrawal, Anurag A. (2016). "Consequences of toxic secondary compounds in nectar for mutualist bees and antagonist butterflies". Ecology. 97 (10): 2570–2579. doi:10.1002/ecy.1483. hdl:1813/66741. ISSN 1939-9170. PMID 27859127.

- MacIvor, James Scott; Roberto, Adriano N.; Sodhi, Darwin S.; Onuferko, Thomas M.; Cadotte, Marc W. (2017). "Honey bees are the dominant diurnal pollinator of native milkweed in a large urban park". Ecology and Evolution. 7 (20): 8456–8462. doi:10.1002/ece3.3394. ISSN 2045-7758. PMC 5648680. PMID 29075462.

- Garber, Steven D. (1998). The Urban Naturalist. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 76–79. ISBN 978-0-486-40399-1.

- Groth, Jacob (November 10, 2000). "Do Farm-Raised Monarchs Migrate?". Swallowtail Farms. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- "Monarch Migration". Monarch Joint Venture. 2013.

- "Butterflies Emerge from Cocoons Aboard Station". NASA. 2009.

- Adams, Jean Ruth (1992). Insect Potpourri: Adventures in Entomology. CRC Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-1-877743-09-2.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae (in Latin). Vol. 1. Stockholm: Laurentius Salvius. p. 471. OCLC 174638949. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- πλήξιππος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema Naturae ed. X: 467. BHL.

- Pyle, Robert Michael (2001). Chasing Monarchs: Migrating with the Butterflies of Passage. Houghton Mifflin Books. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-0-618-12743-6.

- Ackery, P. R.; Vaine-Wright, R. I. (1984). Milkweed butterflies, their cladistics and biology: being an account of the natural history of the Danainae, subfamily of the Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae. British Museum (Natural History), London. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-565-00893-2.

- Smith, David A.; Gugs Lushai and John A. Allen (2005). "A classification of Danaus butterflies (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) based upon data from morphology and DNA". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 144 (2): 191–212. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2005.00169.x.

- Gibbs, Lawrence; Taylor, O. R. (1998). "The White Monarch". Department of Entomology University of Kansas. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- Groth, Jacob (February 12, 2022). "Monarch Butterfly Mutants". Swallowtail Farms. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- Hay-Roe, Miriam M.; Lamas, Gerardo; Nation, James L. (2007). "Pre- and postzygotic isolation and Haldane rule effects in reciprocal crosses of Danaus erippus and Danaus plexippus (Lepidoptera: Danainae), supported by differentiation of cuticular hydrocarbons, establish their status as separate species". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 91 (3): 445–453. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00809.x.

- "Petition to protect the Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus plexippus) under the endangered species act" (PDF). Xerces Society. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- Zhan, Shuai; Merlin, Christine; Boore, Jeffrey L.; Reppert, Steven M. (November 2011). "The Monarch Butterfly Genome Yields Insights into Long-Distance Migration". Cell. 147 (5): 1171–85. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.052. PMC 3225893. PMID 22118469.

- Stensmyr, Marcus C.; Hansson, Bill S. (November 2011). "A Genome Befitting a Monarch". Cell. 147 (5): 970–2. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.009. PMID 22118454. S2CID 16035019.

- Johnson, Carolyn Y. (November 23, 2011). "Monarch butterfly genome sequenced". Boston Globe. Boston, MA. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- Zhan, Shuia; Zhang, Wei; Niitepold, Kristjan; Hsu, Jeremy; Haeger, Juan Fernandez; Zalucki, Myron P.; Altizer, Sonia; de Roode, Jacobus C.; Reppert, Stephen M.; Kronforst, Marcus R. (October 1, 2014). "The genetics of Monarch butterfly migration and warning coloration". Nature. 514 (7522): 317–321. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..317Z. doi:10.1038/nature13812. PMC 4331202. PMID 25274300.

- Zhan, Shuai; Merlin, Christine; Boore, Jeffrey L.; Reppert, Steven M. (November 23, 2012). "The monarch butterfly genome yields insights into long-distance migration". Cell. 147 (5): 1171–1185. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.052. PMC 3225893. PMID 22118469.

- Gasmi, Laila; Boulain, Helene; Gauthier, Jeremy; Hua-Van, Aurelie; Musset, Karine; Jakubowska, Agata K.; Aury, Jean-Marc; Volkoff, Anne-Nathalie; Huguet, Elisabeth (September 17, 2015). "Recurrent Domestication by Lepidoptera of Genes from Their Parasites Mediated by Bracoviruses". PLOS Genetics. 11 (9): e1005470. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005470. PMC 4574769. PMID 26379286.

- Le Page, Michael (September 17, 2015). "If viruses transfer wasp genes into butterflies, are they GM?". New Scientist. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- Main, Douglas (September 17, 2015). "Wasps Have Genetically Modified Butterflies, Using Viruses". Newsweek. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- Oberhauser (2004), p. 3

- "Monarch Butterfly Life Cycle and Migration". National Geographic Education. October 24, 2008. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- "Egg". Monarch Joint Venture. 2021. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- Oberhauser, 2004 & p. 23.

- Lefevre, T.; Chiang, A.; Li, H; Li, J; de Castillejo, C.L.; Oliver, L.; Potini, Y.; Hunter, M. D.; de Roode, J.C. (2012). "Behavioral resistance against a protozoan parasite in the monarch butterfly" (PDF). Journal of Animal Ecology. 81 (1): 70–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01901.x. hdl:2027.42/89483. PMID 21939438.

- "The other butterfly effect – A youth reporter talks to Jaap de Roode". TED Blog. November 25, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- Oberhauser, 2004 & p. 51.

- "Guide to Monarch Instars". Monarch Joint Venture. 2021. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- Collie, Joseph; Granela, Odelvys; Brown, Elizabeth B.; Keene, Alex C. (November 2020). "Aggression Is Induced by Resource Limitation in the Monarch Caterpillar". iScience. 23 (12): 101791. Bibcode:2020iSci...23j1791C. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101791. PMC 7756136. PMID 33376972.

- Petersen, B. (1964). "Humidity, Darkness, and Gold Spots as Possible Factors in Pupal Duration of Monarch Butterflies". Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society. 18: 230–232.

- "Pupa". Monarch Joint Venture. 2021. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- Pocius, V. M.; Debinski, D. M.; Pleasants, J. M.; Bidne, K. G.; Hellmich, R. L.; Brower, L. P. (September 7, 2017). "Milkweed Matters: Monarch Butterfly (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) Survival and Development on Nine Midwestern Milkweed Species". Environmental Entomology. 46 (5): 1098–1105. doi:10.1093/ee/nvx137. ISSN 0046-225X. PMC 5850784. PMID 28961914.

- "Reproduction". Monarch Lab. Regents of the University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on July 16, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- Braby, Michael F. (2000). Butterflies of Australia: Their Identification, Biology and Distribution. CSIRO Publishing. pp. 597–599. ISBN 978-0-643-06591-8.

- Satterfield, Dara A.; Davis, Andrew K. (April 2014). "Variation in wing characteristics of monarch butterflies during migration: Earlier migrants have redder and more elongated wings". Animal Migration. 2 (1). doi:10.2478/ami-2014-0001.

- Davis, A. K.; Holden, Michael T. (2015). "Measuring Intraspecific Variation in Flight-Related Morphology of Monarch Butterflies (Danaus plexippus): Which Sex Has the Best Flying Gear?" (PDF). Journal of Insects. Hindawi Publishing Corporation. 2015 (59170): 1–6. doi:10.1155/2015/591705. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- "Monarch, Danaus plexippus". Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- "Adult". Monarch Joint Venture. 2021. Archived from the original on July 21, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- "Sensory Systems". Biology. Monarch Watch. Archived from the original on March 19, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- "Sexing Monarchs". Biology. Monarch Watch. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- Darby, Gene (1958). What is a Butterfly. Chicago: Benefic Press. p. 10.

- Flockhart, D. T. Tyler; Martin, Tara G.; Norris, D. Ryan (2012). "Experimental Examination of Intraspecific Density-Dependent Competition during the Breeding in Monarch Butterflies (Danaus plexippus)". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e45080. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...745080F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045080. PMC 3440312. PMID 22984614.

- Blackiston, Douglas; Briscoe, Adriana D.; Weiss, Martha R. (February 1, 2011). "Color vision and learning in the monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus (Nymphalidae)". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 214 (Pt 3): 509–520. doi:10.1242/jeb.048728. ISSN 1477-9145. PMID 21228210.

- Stalleicken, Julia; Labhart, Thomas; Mouritsen, Henrik (March 2006). "Physiological characterization of the compound eye in monarch butterflies with focus on the dorsal rim area". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 192 (3): 321–331. doi:10.1007/s00359-005-0073-6. ISSN 0340-7594. PMID 16317560. S2CID 31493135.

- Sauman, Ivo; Briscoe, Adriana D.; Zhu, Haisun; Shi, Dingding; Froy, Oren; Stalleicken, Julia; Yuan, Quan; Casselman, Amy; Reppert, Steven M. (May 5, 2005). "Connecting the Navigational Clock to Sun Compass Input in Monarch Butterfly Brain". Neuron. 46 (3): 457–467. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.014. ISSN 0896-6273. PMID 15882645. S2CID 17755509.

- Cepero, Laurel C.; Rosenwald, Laura C.; Weiss, Martha R. (July 1, 2015). "The Relative Importance of Flower Color and Shape for the Foraging Monarch Butterfly (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)". Journal of Insect Behavior. 28 (4): 499–511. doi:10.1007/s10905-015-9519-z. ISSN 1572-8889. S2CID 18380612.

- Emmel, Thomas C. (1997). Florida's Fabulous Butterflies. p. 44, World Publications, ISBN 0-911977-15-5

- Oberhauser (2004), pp. 61–68.

- Frey, D.; Leong, K. L. H.; Peffer, E.; Smidt, R. K.; Oberhauser, K. S. (1998). "Mating patterns of overwintering monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus (L.)) in California" (PDF). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society. 52: 84–97.

- Solensky, M.J.; K.S. Oberhauser (2009). "Sperm Precedence in Monarch Butterflies (Danaus plexippus)". Behavioral Ecology. 20 (2): 328–34. doi:10.1093/beheco/arp003.

- Oberhauser, K. S. (1989). "Effects of spermatophores on male and female monarch butterfly reproductive success". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 25 (4): 237–246. doi:10.1007/bf00300049. S2CID 6843773.

- "ADW: Danaus plexippus: Information". Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- Solensky, Michelle J. (November 2004). "The Effect of Behavior and Ecology on Male Mating Success in Overwintering Monarch Butterflies (Danaus plexippus)". Journal of Insect Behavior. 17 (6): 723–743. doi:10.1023/b:joir.0000048985.58159.0d. ISSN 0892-7553. S2CID 31954178.

- Gerald McCormack (December 7, 2005). "Cook Islands' Largest Butterfly – the Monarch". Cook Islands Biodiversity.

- Scott, James A. (1986). The Butterflies of North America. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA. ISBN 0-8047-2013-4

- Brower, Lincoln P.; Malcolm, Stephen B. (1991). "Animal Migrations: Endangered Phenomena". American Zoologist. 31 (1): 265–276. doi:10.1093/icb/31.1.265.

- Davis, Donald (November 27, 2014). "DPLEX-L:59250 THE possibility of a trans-Gulf migration, oil rigs, Dr. Gary Ross, and more". Monarch Watch. University of Kansas.

- "Monarch Sightings Map". Monarch Butterfly New Zealand Trust. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- "The lonely flight of the monarch butterfly". NewsAdvance.com, Lynchburg, Virginia Area. October 4, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- "Provisional species list of the Lepidoptera". Gibraltar Ornithological and Natural History Society. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015.

- Pais, Miguel. "Northwestern African sightings of D. plexippus, Maroc>Pappilons>Danaus plexippus". Google Maps. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- Coombes, Simon. "1995 Monarch Invasion of the UK". butterfly-guide.co.uk. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- Cech, Rick and Tudor, Guy (2005). Butterflies of the East Coast. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. ISBN 0-691-09055-6

- Iftner, David C.; Shuey, John A. and Calhoun, John C. (1992). Butterflies and Skippers of Ohio. College of Biological Sciences and The Ohio State University. ISBN 0-86727-107-8

- "Monarch Butterfly Journey North". Annenberg Learner. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- Pyle, Robert Michael (2014). Chasing monarchs: Migrating with the butterflies of passage. Yale University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0395828205.

- Halpern, Sue (2002). Four Wings and a Prayer. Kindle edition location 1594. New York, New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-78720-0.

- "Plant Milkweed for Monarchs" (PDF). Monarch Joint Venture Partnering across the U.S. to conserve the monarch migration. Monarch Joint Venture. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 21, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- USDA, NRCS (n.d.). "Asclepias incarnata". The PLANTS Database (plants.usda.gov). Greensboro, North Carolina: National Plant Data Team.

- Kirk, S.; Belt, S. "Plant fact sheet for swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)" (PDF). Beltsville, Maryland: United States Department of Agriculture: Natural Resources Conservation Service: Norman A. Berg National Plant Materials Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- Holmes, Forest Russell. "Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata L.)". Plant of the Week. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture: United States Forest Service. Archived from the original on March 28, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- "Northeast Region Milkweed Species: Swamp Milkweed: Asclepias incarnata" (PDF). Plant Milkweed for Monarchs. Monarch Joint Venture. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 21, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- "Asclepias nivea". Butterfly gardening & all things milkweed. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- Stevens, Michelle (May 30, 2006). "Plant guide for Asclepias speciosa" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture: Natural Resources Conservation Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- Young-Mathews, A.; Eldredge, E. (2012). "Plant fact sheet for showy milkweed (Asclepias speciosa)" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture: Natural Resources Conservation Service, Corvallis Plant Materials Center, Oregon, and Great Basin Plant Materials Center, Fallon, Nevada. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 1, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- "Asclepias speciosa". Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture: United States Forest Service. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- Wiese, Karen (2000). "Showy Milkweed: Asclepias speciosa". Sierra Nevada wildflowers: a field guide to common wildflowers and shrubs of the Sierra Nevada, including Yosemite, Sequoia, and Kings Canyon National Parks. Helena, Montana: Falcon Publishing, Inc. p. 50. ISBN 0585362831. LCCN 00022385. OCLC 47011272. Retrieved July 12, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

-

- Stevens, Michelle. "Plant guide for common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture: Natural Resources Conservation Service: National Plant Data Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 5, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- Taylor, David. "Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca L.)". Plant of the Week. United States Department of Agriculture: United States Forest Service. Archived from the original on June 4, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- Higgins, Adrian (May 27, 2015). "A gardener's guide to saving the monarch". Home & Garden. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Higgins, Adrian (May 27, 2015). "7 milkweed varieties and where to find them". Home & Garden. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Gomez, Tony (March 14, 2013). "Asclepias syriaca: Common Milkweed for Monarch Caterpillars". Monarch Butterfly Garden. MonarchButterflyGarden.net. Archived from the original on March 16, 2015. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- "Asclepias syriaca". Butterfly gardening & all things milkweed. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- "Northeast Region Milkweed Species: Common Milkweed: Asclepias syriaca" (PDF). Plant Milkweed for Monarchs. Monarch Joint Venture. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 21, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- Davis, Lee (May 31, 2006). "Plant guide for Green Milkweed: Asclepias viridis Walt" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture: Natural Resources Conservation Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- Taylor, David. "Green Antelopehorn (Asclepias viridis)". Plant of the Week. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture: United States Forest Service. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- Borders, Brianna, The Xerces Society; Casey, Allen, USDA-NRCS Missouri; Row, John M., USDA-NRCS Kansas; Wynia, Rich, USDA-NRCS Kansas; King, Randy, USDA-NRCS Arkansas; Jacobs, Alayna, USDA-NRCS Arkansas; Taylor, Chip, Monarch Watch; Mader, Eric, The Xerces Society (June 24, 2013). Walls, Hailey, The Xerces Society; Rich, Kaitlyn, The Xerces Society (eds.). "Asclepias viridis Green antelopehorn" (PDF). Pollinator Plants of the Central United States: Native Milkweeds (Asclepias spp.). Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture: Natural Resources Conservation Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Asclepias viridis: Spider Milkweed". NatureServe. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- "Butterfly Society of Hawaii". Butterfly Society of Hawaii. Retrieved January 6, 2017.