Moncton

Moncton (/ˈmʌŋktən/; French pronunciation: [mɔŋktœn]) is the most populous city in the Canadian province of New Brunswick. Situated in the Petitcodiac River Valley, Moncton lies at the geographic centre of the Maritime Provinces. The city has earned the nickname "Hub City" because of its central inland location in the region and its history as a railway and land transportation hub for the Maritimes. As of the 2021 Census, the city had a population of 79,470. The metropolitan population in 2022 was 171,608, making it the fastest growing CMA in Canada for the year with a growth rate of 5.3%.[7] Its land area is 140.67 km2 (54.31 sq mi).[2]

Moncton | |

|---|---|

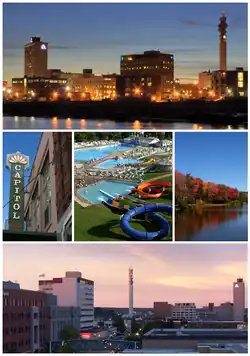

From top, left to right: Moncton skyline at night, the Capitol Theatre, Magic Mountain, Centennial Park, and Downtown Moncton at dusk | |

Logo | |

| Nicknames: | |

| Motto: "I rise again" | |

Interactive map outlining Moncton | |

Moncton Location of Moncton in Canada  Moncton Moncton (New Brunswick) | |

| Coordinates: 46°07′58″N 64°46′17″W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | New Brunswick |

| County | Westmorland |

| Parish | Moncton Parish |

| First settled | 1733 |

| Founded | 1766 |

| Incorporated | 1855, 1875 |

| Named for | Robert Monckton |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Dawn Arnold |

| • Governing Body | Moncton City Council |

| • MP | Ginette Petitpas Taylor |

| • MLAs | Ernie Steeves Daniel Allain Rob McKee Greg Turner Sherry Wilson |

| Area | |

| • City | 140.67 km2 (54.31 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 110.73 km2 (42.75 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,562.47 km2 (989.38 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 70 m (230 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population | |

| • City | 79,470 |

| • Density | 564/km2 (1,460/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 119,785 |

| • Urban density | 1,081.8/km2 (2,802/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 157,717 |

| • Metro density | 61.5/km2 (159/sq mi) |

| • Demonym | Monctonian |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (AST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−3 (ADT) |

| Canadian Postal code | |

| Area code | 506 |

| NTS Map | 21I2 Moncton |

| GNBC Code | DADHJ[5] |

| Highways | |

| GDP (Moncton CMA) | CA$6.9 billion (2016)[6] |

| GDP per capita (Moncton CMA) | CA$47,959 (2016) |

| Website | www |

Although the Moncton area was first settled in 1733, Moncton was officially founded in 1766 with the arrival of Pennsylvania German immigrants from Philadelphia. Initially an agricultural settlement, Moncton was not incorporated until 1855. It was named for Lt. Col. Robert Monckton, the British officer who had captured nearby Fort Beauséjour a century earlier. A significant wooden shipbuilding industry had developed in the community by the mid-1840s, allowing for the civic incorporation in 1855. But the shipbuilding economy collapsed in the 1860s, causing the town to lose its civic charter in 1862. Moncton regained its charter in 1875 after the community's economy rebounded, mainly due to a growing railway industry. In 1871, the Intercolonial Railway of Canada chose Moncton as its headquarters, and Moncton remained a railway town for well over a century until the Canadian National Railway (CNR) locomotive shops closed in the late 1980s.

Although Moncton's economy was traumatized twice—by the collapse of the shipbuilding industry in the 1860s and by the closure of the CNR locomotive shops in the 1980s—the city was able to rebound strongly on both occasions. It adopted the motto Resurgo (Latin: "I rise again") after its rebirth as a railway town.[8] Its economy is stable and diversified, primarily based on its traditional transportation, distribution, retailing, and commercial heritage, and supplemented by strength in the educational, health care, financial, information technology, and insurance sectors. The strength of Moncton's economy has received national recognition and the local unemployment rate is consistently less than the national average.

On 1 January 2023, Moncton annexed an area including Charles Lutes Road and Zack Road;[9][10] revised census information has not been released.

History

Acadians settled the head of the Bay of Fundy in the 1670s.[11] The first reference to the "Petcoucoyer River" was on the De Meulles map of 1686.[12] Settlement of the Petitcodiac and Memramcook river valleys began about 1700, gradually extending inland and reaching the site of present-day Moncton in 1733. The first Acadian settlers in the Moncton area established a marshland farming community and chose to name their settlement Le Coude ("The Elbow"),[13] an allusion to the 90° bend in the river near the site of the settlement.

In 1755, nearby Fort Beausejour was captured by British forces under the command of Lt. Col. Robert Monckton.[14] The Beaubassin region including the Memramcook and Petitcodiac river valleys subsequently fell under English control.[15] Later that year, Governor Charles Lawrence issued a decree ordering the expulsion of the Acadian population from Nova Scotia (including recently captured areas of Acadia such as Le Coude). This action came to be known as the "Great Upheaval".[16]

The reaches of the upper Petitcodiac River valley then came under the control of the Philadelphia Land Company (one of the principals of which was Benjamin Franklin.) In 1766, Pennsylvania German settlers arrived to reestablish the preexisting farming community at Le Coude.[17] The Settlers consisted of eight families: Heinrich Stief (Steeves), Jacob Treitz (Trites), Matthias Sommer (Somers), Jacob Reicker (Ricker), Charles Jones (Schantz),[18] George Wortmann (Wortman), Michael Lutz (Lutes), and George Koppel (Copple). There is a plaque dedicated in their honour at the mouth of Hall's Creek.[19] They renamed the settlement "The Bend".[13] The Bend remained an agricultural settlement for nearly 80 more years. Even by 1836, there were only 20 households in the community. At that time, the Westmorland Road became open to year-round travel and a regular mail coach service was established between Saint John and Halifax. The Bend became an important transfer and rest station along the route. Over the next decade, lumbering and then shipbuilding became important industries in the area.

The community's turning point came when Joseph Salter took over (and expanded) a shipyard at the Bend in 1847. The shipyard grew to employ about 400 workers. The Bend subsequently developed a service-based economy to support the shipyard and gradually began to acquire all the amenities of a growing town.[20] The prosperity engendered by the wooden shipbuilding industry allowed The Bend to incorporate as the town of Moncton in 1855. Although the town was named for Monckton,[13] a clerical error at the time the town was incorporated resulted in the misspelling of its name, which has remained to the present day. Moncton's first mayor was the shipbuilder Joseph Salter.

In 1857, the European and North American Railway opened its line from Moncton to nearby Shediac. This was followed in 1859 by a line from Moncton to Saint John.[21] At about the time of the railway's arrival, the popularity of steam-powered ships forced an end to the era of wooden shipbuilding. The Salter shipyard closed in 1858. The resulting industrial collapse caused Moncton to surrender its civic charter in 1862.[13]

Moncton's economic depression did not last long; a second era of prosperity came to the area in 1871, when Moncton was selected to be the headquarters of the Intercolonial Railway of Canada (ICR).[13] The arrival of the ICR in Moncton was a seminal event for the community. For the next 120 years, the history of the city was firmly linked with the railway's. In 1875,[13] Moncton reincorporated as a town, and a year later, the ICR line to Quebec opened. The railway boom that emanated from this and the associated employment growth allowed Moncton to achieve city status on April 23, 1890.[22]

.jpg.webp)

Moncton grew rapidly during the early 20th century, particularly after provincial lobbying helped the city become the eastern terminus of the massive National Transcontinental Railway project in 1912.[23] In 1918, the federal government merged the ICR and the National Transcontinental Railway (NTR) into the newly formed Canadian National Railways (CNR) system.[23] The ICR shops became CNR's major locomotive repair facility for the Maritimes and Moncton became the headquarters for CNR's Maritime division.[24] The T. Eaton Company's catalogue warehouse moved to the city in the early 1920s, employing over 700 people.[25] Transportation and distribution became increasingly important to Moncton's economy in the mid-20th century. The first scheduled air service out of Moncton was established in 1928. During the Second World War, the Canadian Army built a large military supply base in the city to service the Maritime military establishment. The CNR continued to dominate the economy of the city; railway employment in Moncton peaked at nearly 6,000 workers in the 1950s before beginning a slow decline.[26]

Moncton was placed on the Trans-Canada Highway network in the early 1960s after Route 2 was built along the city's northern perimeter. Later, the Route 15 was built between the city and Shediac.[27] At the same time, the Petitcodiac River Causeway was constructed.[13] The Université de Moncton was founded in 1963[28] and became an important resource in the development of Acadian culture in the area.[29]

The late 1970s and the 1980s were a period of economic hardship for the city as several major employers closed or restructured.[30] The Eatons catalogue division, CNR's locomotive shops facility and CFB Moncton closed during this time,[31] throwing thousands of citizens out of work.[32]

The city diversified in the early 1990s with the rise of information technology, led by call centres that made use of the city's bilingual workforce.[33] By the late 1990s, retail, manufacturing and service expansion began to occur in all sectors and within a decade of the closure of the CNR locomotive shops Moncton had more than made up for its employment losses. This dramatic turnaround in the city's fortunes has been termed the "Moncton Miracle".[34]

The community's growth has continued unabated since the 1990s, actually accelerating. The confidence of the community has been bolstered by its ability to host major events such as the Francophonie Summit in 1999, a Rolling Stones concert in 2005, the Memorial Cup in 2006, and both the IAAF World Junior Championships in Athletics and a neutral site regular season CFL football game in 2010.[35] Positive developments include the Atlantic Baptist University (later renamed Crandall University) achieving full university status and relocating to a new campus in 1996, the Greater Moncton Roméo LeBlanc International Airport opening a new terminal building and becoming a designated international airport in 2002,[36] and the opening of the new Gunningsville Bridge to Riverview in 2005.[37] In 2002, Moncton became Canada's first officially bilingual city.[38] In the 2006 census, it was designated a Census Metropolitan Area and became New Brunswick's largest metropolitan area.[39]

Geography

Moncton lies in southeastern New Brunswick, at the geographic centre of the Maritime Provinces. The city is along the north bank of the Petitcodiac River at a point where the river bends acutely from west−east to north−south flow. This geographical feature has contributed significantly to historical names for the community. Petitcodiac in the Mi'kmaq language has been translated as "bends like a bow". The early Acadian settlers in the region named their community Le Coude ("the elbow").[13] Subsequent English immigrants changed the settlement's name to The Bend of the Petitcodiac (or simply "The Bend").[13]

The Petitcodiac river valley at Moncton is broad and relatively flat, bounded by a long ridge to the north (Lutes Mountain) and by the rugged Caledonia Highlands to the south. Moncton lies at the original head of navigation on the river, but a causeway to Riverview (constructed in 1968) resulted in extensive sedimentation of the river channel downstream and rendered the Moncton area of the waterway unnavigable.[13] On April 14, 2010, the causeway gates were opened in an effort to restore the silt-laden river.[40]

Tidal bore

The Petitcodiac River exhibits one of North America's few tidal bores: a regularly occurring wave that travels up the river on the leading edge of the incoming tide. The bore is a result of the Bay of Fundy's extreme tides. Originally, the bore was very impressive, sometimes between 1 and 2 metres (3 ft 3 in and 6 ft 7 in) high and extending across the 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) width of the Petitcodiac River in the Moncton area. This wave occurred twice a day at high tide, travelling at an average speed of 13 km/h (8.1 mph) and producing an audible roar.[41] Unsurprisingly, the "bore" became a very popular early tourist attraction for the city, but when the Petitcodiac causeway was built in the 1960s, the river channel quickly silted in and reduced the bore so that it rarely exceeded 15 to 20 centimetres (5.9 to 7.9 in) in height.[42] On April 14, 2010, the causeway gates were opened in an effort to restore the silt-laden river.[40] A recent tidal bore since the opening of the causeway gates measured a 2-foot-high (0.61 m) wave, unseen for many years.[43]

Climate

Despite being less than 50 km (31 mi) from the Bay of Fundy and less than 30 km (19 mi) from the Northumberland Strait, the climate tends to be more continental than maritime during the summer and winter seasons, with maritime influences somewhat tempering the transitional seasons of spring and autumn.[44]

Moncton has a warm summer humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb) with uniform precipitation distribution. Winter days are typically cold but sunny, with solar radiation generating some warmth. Daytime high temperatures usually range a few degrees below the freezing point. Major snowfalls can result from Nor'easter ocean storms moving up the east coast of North America.[45] These major snowfalls typically average 20–30 cm (8–12 in) and are frequently mixed with rain or freezing rain. Spring is often delayed because the sea ice that forms in the nearby Gulf of St. Lawrence during the winter requires time to melt, and this cools onshore winds, which can extend inland as far as Moncton. The ice burden in the gulf has diminished considerably over the last decade,[46] and the springtime cooling effect has weakened as a result. Daytime temperatures above freezing are typical by late February. Trees are usually in full leaf by late May.[47] Summers are warm, sometimes hot, as well as humid due to the seasonal prevailing westerly winds strengthening the climate's continental tendencies.[44] Daytime highs sometimes reach more than 30 °C (86 °F). Rainfall is generally modest, especially in late July and August, and periods of drought are not uncommon.[47] Autumn daytime temperatures remain mild until late October.[44] First snowfalls usually do not occur until late November and consistent snow cover on the ground does not happen until late December. New Brunswick's Fundy coast occasionally experiences the effects of post-tropical storms.[47] The stormiest weather of the year, with the greatest precipitation and the strongest winds, usually occurs during the fall/winter transition (November to mid-January).[47]

The highest temperature ever recorded in Moncton was 37.8 °C (100 °F) on August 18 and 19, 1935.[48] The coldest ever recorded was −37.8 °C (−36 °F) on February 5, 1948.[49]

| Climate data for Moncton, 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1881–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.2 (63.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

34.5 (94.1) |

34.4 (93.9) |

36.1 (97.0) |

37.8 (100.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

18.3 (64.9) |

37.8 (100.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −3.2 (26.2) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

2.7 (36.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.9 (71.4) |

25.3 (77.5) |

24.7 (76.5) |

20.0 (68.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

6.4 (43.5) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

11.2 (52.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −8.2 (17.2) |

−7 (19) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

4.2 (39.6) |

10.7 (51.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

19.5 (67.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

2.5 (36.5) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

6.1 (43.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −13.1 (8.4) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

4.9 (40.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

13.2 (55.8) |

8.9 (48.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

0.9 (33.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −36.7 (−34.1) |

−37.8 (−36.0) |

−31.7 (−25.1) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−21.1 (−6.0) |

−34.4 (−29.9) |

−37.8 (−36.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 97.7 (3.85) |

84.0 (3.31) |

105.9 (4.17) |

92.0 (3.62) |

101.7 (4.00) |

88.0 (3.46) |

84.8 (3.34) |

76.6 (3.02) |

93.7 (3.69) |

105.9 (4.17) |

93.8 (3.69) |

100.0 (3.94) |

1,124 (44.25) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 30.3 (1.19) |

30.2 (1.19) |

47.4 (1.87) |

63.4 (2.50) |

96.8 (3.81) |

88.0 (3.46) |

84.8 (3.34) |

76.6 (3.02) |

93.7 (3.69) |

104.6 (4.12) |

77.1 (3.04) |

49.1 (1.93) |

842.0 (33.15) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 67.4 (26.5) |

53.8 (21.2) |

58.5 (23.0) |

28.5 (11.2) |

4.9 (1.9) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.3 (0.5) |

16.7 (6.6) |

50.8 (20.0) |

282.0 (111.0) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 14.6 | 11.8 | 13.6 | 14.2 | 14.8 | 13.4 | 12.5 | 10.9 | 11.4 | 13.1 | 15.3 | 15.3 | 160.8 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 4.8 | 4.3 | 7.0 | 11.3 | 14.6 | 13.4 | 12.5 | 10.9 | 11.4 | 12.9 | 12.6 | 7.1 | 122.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 11.7 | 9.1 | 8.7 | 5.2 | 0.75 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.36 | 4.3 | 10.1 | 50.1 |

| Source: Environment Canada[49][50][51][48] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Greater Moncton Roméo LeBlanc International Airport, 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1939–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 18.2 | 15.8 | 28.0 | 30.0 | 37.6 | 40.9 | 43.7 | 44.5 | 40.9 | 32.5 | 28.2 | 20.3 | 44.5 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.1 (61.0) |

15.3 (59.5) |

26.1 (79.0) |

28.5 (83.3) |

34.2 (93.6) |

34.4 (93.9) |

35.6 (96.1) |

37.2 (99.0) |

34.1 (93.4) |

26.9 (80.4) |

22.9 (73.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

37.2 (99.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −3.7 (25.3) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

2.0 (35.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.0 (75.2) |

19.5 (67.1) |

12.8 (55.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

10.7 (51.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −8.9 (16.0) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

3.5 (38.3) |

10.0 (50.0) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.8 (65.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

7.6 (45.7) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

5.4 (41.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −14 (7) |

−12.7 (9.1) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

4.0 (39.2) |

9.1 (48.4) |

12.9 (55.2) |

12.2 (54.0) |

7.7 (45.9) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

0.1 (32.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −32.2 (−26.0) |

−31.7 (−25.1) |

−27.4 (−17.3) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

1.2 (34.2) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−10 (14) |

−17.4 (0.7) |

−29 (−20) |

−32.2 (−26.0) |

| Record low wind chill | −49.4 | −46.0 | −39.3 | −27.7 | −12.6 | −4.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −9.0 | −14.7 | −27.1 | −43.5 | −49.4 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 103.3 (4.07) |

90.9 (3.58) |

115.6 (4.55) |

97.6 (3.84) |

96.9 (3.81) |

94.6 (3.72) |

92.1 (3.63) |

80.8 (3.18) |

93.5 (3.68) |

113.4 (4.46) |

107.2 (4.22) |

114.4 (4.50) |

1,200.4 (47.26) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 28.8 (1.13) |

28.4 (1.12) |

49.2 (1.94) |

62.3 (2.45) |

92.5 (3.64) |

94.6 (3.72) |

92.1 (3.63) |

80.8 (3.18) |

93.5 (3.68) |

112.1 (4.41) |

87.3 (3.44) |

54.2 (2.13) |

875.7 (34.48) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 78.1 (30.7) |

64.7 (25.5) |

64.5 (25.4) |

31.2 (12.3) |

3.8 (1.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.2 (0.5) |

19.4 (7.6) |

62.4 (24.6) |

325.3 (128.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 16.6 | 13.7 | 14.7 | 15.3 | 15.6 | 15.1 | 14.1 | 12.2 | 11.7 | 13.8 | 16.0 | 16.5 | 175.5 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 5.9 | 4.8 | 7.7 | 12.3 | 15.4 | 15.1 | 14.1 | 12.2 | 11.7 | 13.7 | 12.9 | 8.1 | 134.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 14.2 | 12.0 | 10.9 | 6.5 | 0.90 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.41 | 5.5 | 12.3 | 62.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 116.2 | 124.3 | 139.9 | 165.6 | 207.5 | 232.8 | 256.3 | 241.1 | 173.3 | 149.4 | 95.1 | 101.1 | 2,002.2 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 41.3 | 42.7 | 37.9 | 40.8 | 44.8 | 49.4 | 53.8 | 55.0 | 45.9 | 44.0 | 33.4 | 37.5 | 43.9 |

| Source: Environment Canada[52][53][54][55] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Moncton generally remains a "low rise" city, but its skyline encompasses buildings and structures with varying architectural styles from many periods. The city's most dominant structure is the Bell Aliant Tower, a 127 metres (417 ft) microwave communications tower built in 1971. When it was constructed, it was the tallest microwave communications tower of its kind in North America. It remains the tallest structure in Moncton, dwarfing the neighbouring Place L’Assomption by 46 metres (151 ft).[56] Indeed, the Bell Aliant Tower is also the tallest free-standing structure in all four Atlantic provinces. Assumption Place is a 20-story office building and the headquarters of Assumption Mutual Life Insurance. This building is 81 metres (266 ft) tall and tied with Brunswick Square (Saint John) as the tallest building in the province.[57] The Blue Cross Centre is a nine-story building in Downtown Moncton. It is architecturally distinctive, encompasses a full city block, and is the city's largest office building by square footage.[58] It is the home of Medavie Blue Cross and the Moncton Public Library. There are about a half dozen other buildings in Moncton between eight and 12 stories, including the Delta Beausejour and Brunswick Crowne Plaza Hotels and the Terminal Plaza office complex.

Urban parks

The most popular park in the area is Centennial Park, which contains an artificial beach, lighted cross country skiing and hiking trails, the city's largest playground, lawn bowling and tennis facilities, a boating pond, a treetop adventure course, and Rocky Stone Field, a city owned 2,500 seat football stadium with artificial turf, and home to the Moncton Minor Football Association.[59] The city's other main parks are Mapleton Park in the city's north end, Irishtown Nature Park (one of the largest urban nature parks in Canada) and St. Anselme Park (located in Dieppe). The numerous neighbourhood parks throughout the metro Moncton area include Bore View Park (which overlooks the Petitcodiac River), and the downtown Victoria Park, which features a bandshell, flower gardens, fountain, and the city's cenotaph.[60] There is an extensive system of hiking and biking trails in Metro Moncton. The Riverfront Trail is part of the Trans Canada Trail system, and various monuments and pavilions can be found along its length.[61]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1861 | 1,396 | — |

| 1871 | 600 | −57.0% |

| 1881 | 5,032 | +738.7% |

| 1891 | 8,762 | +74.1% |

| 1901 | 9,026 | +3.0% |

| 1911 | 11,345 | +25.7% |

| 1921 | 17,488 | +54.1% |

| 1931 | 20,689 | +18.3% |

| 1941 | 22,763 | +10.0% |

| 1951 | 27,334 | +20.1% |

| 1956 | 36,003 | +31.7% |

| 1961 | 43,840 | +21.8% |

| 1966 | 45,847 | +4.6% |

| 1971 | 54,864 | +19.7% |

| 1976 | 55,934 | +2.0% |

| 1981 | 54,741 | −2.1% |

| 1986 | 55,468 | +1.3% |

| 1991 | 56,823 | +2.4% |

| 1996 | 59,313 | +4.4% |

| 2001 | 61,046 | +2.9% |

| 2006 | 64,128 | +5.0% |

| 2011 | 69,074 | +7.7% |

| 2016 | 71,889 | +4.1% |

| 2021 | 79,470 | +10.5% |

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, the City of Moncton had a population of 79,470 living in 35,118 of its 37,318 total private dwellings, a change of 10.5% from its 2016 population of 71,889. With a land area of 140.67 km2 (54.31 sq mi), it had a population density of 564.9/km2 (1,463.2/sq mi) in 2021.[62]

Moncton's urban area (population centre) had a population of 119,785 living in an area of 110.73 km2 (42.75 sq mi). Residents lived in 51,830 dwellings out of the 54,519 total private dwellings.[4]

Greater Moncton, the Census Metropolitan Area (CMA), had a population of 157,717 living in 67,179 of its 70,460 total private dwellings; a change of 8.9% from its 2016 population of 144,810. The CMA includes the neighbouring city of Dieppe and the town of Riverview, as well as adjacent suburban areas in Westmorland and Albert counties.[63] With a land area of 2,562.47 km2 (989.38 sq mi), it had a population density of 61.5/km2 (159.4/sq mi) in 2021.[64]

Moncton's urban area is the third largest in Atlantic Canada, after Halifax, Nova Scotia, and St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador, and the second largest in The Maritimes.

In 2016, the median age in Moncton was 41.4, close to the national median age of 41.2.

The 2021 census reported that immigrants (individuals born outside Canada) comprise 8,460 persons or 10.9% of the total population of Moncton. Of the total immigrant population, the top countries of origin were Philippines (795 persons or 9.4%), India (655 persons or 7.7%), United States of America (555 persons or 6.6%), China (475 persons or 5.6%), Nigeria (470 persons or 5.6%), United Kingdom (395 persons or 4.7%), Syria (385 persons or 4.6%), South Korea (380 persons or 380%), France (290 persons or 3.4%), and Democratic Republic of the Congo (270 persons or 3.2%).[65]

Ethnicity

As of 2021, approximately 82.4% of Moncton's residents were of European ancestry, while 14.9% were visible minorities and 2.7% were Indigenous.[65] The largest ethnic minority groups in Moncton were Black (5.3%), South Asian (3.0%), Arab (1.5%), Filipino (1.3%), Chinese (0.9%), Southeast Asian (0.8%), Korean (0.7%), and Latin American (0.7%).[65]

| Panethnic group | 2021[65] | 2016[66] | 2011[67] | 2006[68] | 2001[69] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| European[lower-alpha 1] | 63,780 | 82.4% | 63,130 | 90.04% | 62,730 | 93% | 60,575 | 96.2% | 58,450 | 97.29% |

| African | 4,075 | 5.26% | 1,830 | 2.61% | 1,180 | 1.75% | 710 | 1.13% | 555 | 0.92% |

| South Asian | 2,310 | 2.98% | 330 | 0.47% | 490 | 0.73% | 265 | 0.42% | 145 | 0.24% |

| Indigenous | 2,080 | 2.69% | 1,795 | 2.56% | 1,415 | 2.1% | 640 | 1.02% | 470 | 0.78% |

| Southeast Asian[lower-alpha 2] | 1,595 | 2.06% | 665 | 0.95% | 505 | 0.75% | 115 | 0.18% | 95 | 0.16% |

| East Asian[lower-alpha 3] | 1,300 | 1.68% | 1,085 | 1.55% | 690 | 1.02% | 275 | 0.44% | 215 | 0.36% |

| Middle Eastern[lower-alpha 4] | 1,260 | 1.63% | 950 | 1.35% | 270 | 0.4% | 185 | 0.29% | 65 | 0.11% |

| Latin American | 565 | 0.73% | 195 | 0.28% | 85 | 0.13% | 55 | 0.09% | 25 | 0.04% |

| Other/multiracial[lower-alpha 5] | 440 | 0.57% | 135 | 0.19% | 85 | 0.13% | 150 | 0.24% | 65 | 0.11% |

| Total responses | 77,405 | 97.4% | 70,115 | 97.53% | 67,450 | 97.65% | 62,965 | 98.19% | 60,080 | 98.42% |

| Total population | 79,470 | 100% | 71,889 | 100% | 69,074 | 100% | 64,128 | 100% | 61,046 | 100% |

| Note: Totals greater than 100% due to multiple origin responses | ||||||||||

Language

| Census | Total | English |

French |

English & French |

Other | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Responses | Count | Trend | Pop % | Count | Trend | Pop % | Count | Trend | Pop % | Count | Trend | Pop % | |||||

2021 |

78,210 |

45,765 | 58.52% | 21,375 | 27.33% | 2,230 | 2.85% | 8,470 | 10.83% | |||||||||

2016 |

70,670 |

43,720 | 61.87% | 21,580 | 30.54% | 1,245 | 1.76% | 4,120 | 5.83% | |||||||||

2011 |

67,930 |

43,030 | — | 63.34% | 21,275 | — | 31.32% | 1,075 | — | 1.58% | 2,550 | — | 3.75% | |||||

Moncton is a bilingual city, 58.5% of its residents having English as their mother tongue, while 27.3% have French, 2.9% learned both English and French as a first language, and 10.8% speak another language as their mother tongue.[70] About 46% of the city population is bilingual and understands both English and French;[71] the only other Canadian cities that approach this level of linguistic duality are Ottawa, Sudbury, and Montreal. Moncton became the first officially bilingual city in the country in 2002. This means that all municipal services, as well as public notices and information, are available in both French and English.[38] The adjacent city of Dieppe is about 64% Francophone and has benefited from an ongoing rural depopulation of the Acadian Peninsula and areas in northern and eastern New Brunswick.[71] The town of Riverview meanwhile is heavily (95%) Anglophone.[71]

Common non-official languages spoken as mother tongues are Arabic (1.4%), Punjabi (0.7%), Chinese Languages (0.7%), Tagalog (0.6%), Korean (0.6%), Spanish (0.6%), Vietnamese (0.5%), and Portuguese (0.5%). 1.2% of residents listed both English and a non-official language as mother tongues, while 0.4% listed both French and a non-official language.

Religion

According to the 2021 census, religious groups in Moncton included:[72]

- Christianity (45,645 persons or 59.0%)

- Irreligion (26,615 persons or 34.4%)

- Islam (2,485 persons or 3.2%)

- Hinduism (995 persons or 1.3%)

- Sikhism (605 persons or 0.8%)

- Judaism (205 persons or 0.3%)

- Buddhism (180 persons or 0.2%)

- Indigenous Spirituality (10 persons or <0.1%)

- Other (660 persons or 0.9%)

Economy

The underpinnings of the local economy are based on Moncton's heritage as a commercial, distribution, transportation, and retailing centre. This is due to Moncton's central location in the Maritimes: it has the largest catchment area in Atlantic Canada with 1.6 million people living within a three-hour drive of the city.[73] The insurance, information technology, educational, and health care sectors also are major factors in the local economy with the city's two hospitals alone employing over five thousand people, along with a growing high tech sector that includes companies such as Nanoptix,[74] International Game Technology, OAO Technology Solutions, BMM Test Labs, TrustMe,[75] and BelTek Systems Desig.[76]

Moncton has garnered national attention because of the strength of its economy. The local unemployment rate averages around 6%, which is below the national average.[77] In 2004 Canadian Business magazine named it "The best city for business in Canada",[78] and in 2007 FDi magazine named it the fifth most business-friendly small-sized city in North America.[79]

Moncton's high proportion of bilingual workers and its status as border-city between majority francophone and majority anglophone areas makes it an attractive centre for both federal employment and the stationing of call-centres for Canadian companies (who provide services in both languages). The city is home to the regional head offices for several Canadian federal agencies such as Corrections Canada, Transport Canada, the Gulf Fisheries Centre and the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency. There are 37 call centres in the city which employ over 5,000 people. Some of the larger centres include Asurion, Numeris (formerly BBM Canada), Exxon Mobil, Royal Bank of Canada, Tangerine Bank (formerly ING Direct), UPS, Fairmont Hotels and Resorts, Rogers Communications, and Nordia Inc.[80]

A number of nationally or regionally prominent corporations have their head offices in Moncton including Atlantic Lottery Corporation, Assumption Life Insurance, Medavie Blue Cross Insurance, Armour Transportation Systems and Major Drilling Group International. TD Bank announced in 2018 a new banking services centre to be located in Moncton which will employ over 1,000 people (including a previously announced customer contact centre).[81] Meanwhile several arms of the Irving corporation have their head offices and/or major operations in greater Moncton. These include Midland Transport, Majesta/Royale Tissues, Irving Personal Care, Master Packaging, Brunswick News, and Cavendish Farms. Kent Building Supplies (an Irving subsidiary) opened their main distribution centre in the Caledonia Industrial Park in 2014. The Irving group of companies employs several thousand people in the Moncton region.[82]

There are three large industrial parks in the metropolitan area. The Irving operations are concentrated in the Dieppe Industrial Park. The Moncton Industrial Park in the city's west end has been expanded. Molson/Coors opened a brewery in the Caledonia Industrial Park in 2007, its first new brewery in over fifty years.[83] All three industrial parks also have large concentrations of warehousing and regional trucking facilities.

A new four-lane Gunningsville Bridge was opened in 2005, connecting downtown Riverview directly with downtown Moncton. On the Moncton side, the bridge connects with an extension of Vaughan Harvey Boulevard as well as to Assumption Boulevard and will serve as a catalyst for economic growth in the downtown area.[84] This has become already evident as an expansion to the Blue Cross Centre was completed in 2006 and a Marriott Residence Inn opened in 2008. The new regional law courts on Assumption Blvd opened in 2011. A new 8,800 seat downtown arena (the Avenir Centre) recently opened in September 2018. On the Riverview side, the Gunningsville Bridge now connects to a new ring road around the town and is expected to serve as a catalyst for development in east Riverview.[84]

The retail sector in Moncton has become one of the most important pillars of the local economy. Major retail projects such as Champlain Place in Dieppe and the Wheeler Park Power Centre on Trinity Drive have become major destinations for locals and for tourists alike.[85][86]

Tourism is an important industry in Moncton and historically owes its origins to the presence of two natural attractions, the tidal bore of the Petitcodiac River (see above) and the optical illusion of Magnetic Hill. The tidal bore was the first phenomenon to become an attraction but the construction of the Petitcodiac causeway in the 1960s effectively extirpated the attraction.[41] Magnetic Hill, on the city's northwest outskirts, is the city's most famous attraction. The Magnetic Hill area includes (in addition to the phenomenon itself), a golf course, major water park, zoo, and an outdoor concert facility. A $90 million casino/hotel/entertainment complex opened at Magnetic Hill in 2010.

Culture

Moncton's Capitol Theatre, an 800-seat restored 1920s-era vaudeville house on Main Street, is the main centre for cultural entertainment for the city.[87][88] The theatre hosts a performing arts series and provides a venue for various theatrical performances as well as Symphony New Brunswick and the Atlantic Ballet Theatre of Canada.[87] The adjacent Empress Theatre offers space for smaller performances and recitals.[87] The Molson Canadian Centre at Casino New Brunswick provides a 2,000-seat venue for major touring artists and performing groups.

The Moncton-based Atlantic Ballet Theatre tours mainly in Atlantic Canada but also tours nationally and internationally on occasion.[89] Théâtre l'Escaouette is a Francophone live theatre company which has its own auditorium and performance space on Botsford Street. The Anglophone Live Bait Theatre is based in the nearby university town of Sackville. There are several private dance and music academies in the metropolitan area, including the Capitol Theatre's own performing arts school.

The Aberdeen Cultural Centre is a major Acadian cultural cooperative containing multiple studios and galleries. Among other tenants, the centre houses the Galerie Sans Nom, the principal private art gallery in the city.[90]

The city's two main museums are the Moncton Museum at Resurgo Place on Mountain Road[91] and the Musée acadien at Université de Moncton.[92] The Moncton Museum reopened following major renovations and an expansion to include the Transportation Discovery Centre. The Discovery Centre includes many hands on exhibits highlighting the city's transportation heritage. The city also has several recognized historical sites. The Free Meeting House was built in 1821 and is a New England–style meeting house located adjacent to the Moncton Museum.[93] The Thomas Williams House, a former home of a city industrialist built in 1883, is now maintained in period style and serves as a genealogical research centre and is also home to several multicultural organizations.[93] The Treitz Haus is located on the riverfront adjacent to Bore View Park and has been dated to 1769 both by architectural style and by dendrochronology.[94] It is the only surviving building from the Pennsylvania Dutch era and is the oldest surviving building in the province of New Brunswick.

In film production, the city has since 1974 been home to the National Film Board of Canada's French-language Studio Acadie.[95]

Moncton is home to the Frye Festival, an annual bilingual literary celebration held in honour of world-renowned literary critic and favourite son Northrop Frye. This event attracts noted writers and poets from around the world and takes place in the month of April.[96]

The Atlantic Nationals Automotive Extravaganza, held each July, is the largest annual gathering of classic cars in Canada.[97] Other notable events include The Atlantic Seafood Festival[98] in August, The HubCap Comedy Festival,[99] and the World Wine Festival, both held in the spring.

Our Lady of the Assumption Cathedral is the location of an interpretation centre, Monument for Recognition in the 21st century (MR21).[100]

Sports

Facilities

The Avenir Centre[101] is an 8,800-seat arena which serves as a venue for major concerts and sporting events and is the home of the Moncton Wildcats of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League and the Moncton Magic of the National Basketball League of Canada. The CN Sportplex is a major recreational facility which has been built on the former CN Shops property. It includes ten ballfields, six soccer fields, an indoor rink complex with four ice surfaces (the Superior Propane Centre) and the Hollis Wealth Sports Dome, an indoor air supported multi-use building. The Sports Dome is large enough to allow for year-round football, soccer and golf activities. A newly constructed YMCA near the CN Sportsplex has extensive cardio and weight training facilities, as well as three indoor pools. The CEPS at Université de Moncton contains an indoor track and a 37.5 metres (123 ft) swimming pool with diving towers.[102] The new Moncton Stadium, also located at the U de M campus was built for the 2010 IAAF World Junior Track & Field Championships. It has a permanent seating for 10,000, but is expandable to a capacity of over 20,000 for events such as professional Canadian football. The only velodrome in Atlantic Canada is in Dieppe. It has since been closed after 17 years of existence due to safety concerns in May 2018.[103][104] The metro area has a total of 12 indoor hockey rinks and one curling club, Curl Moncton. Other public sporting and recreational facilities are scattered throughout the metropolitan area, including a new $18 million aquatic centre in Dieppe opened in 2009.

Sports teams

The Moncton Wildcats play major junior hockey in the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League (QMJHL). They won the President's Cup, the QMJHL championship in both 2006 and 2010.[105] Historically there has been a longstanding presence of a Moncton-based team in the Maritime Junior A Hockey League, but the Dieppe Commandos (formerly known as the Moncton Beavers) relocated to Edmundston at the end of the 2017 season.[106] Historically, Moncton also was home to a professional American Hockey League franchise from 1978 to 1994. The New Brunswick Hawks won the AHL Calder Cup by defeating the Binghamton Whalers in 1981–1982. The Moncton Mets played baseball in the New Brunswick Senior Baseball League and won the Canadian Senior Baseball Championship in 2006.[107] In 2015, the Moncton Fisher Cats began play in the New Brunswick Senior Baseball League. They were formed by a merger between the Moncton Mets and the Hub City Brewers of the NBSBL. In 2011, the Moncton Miracles began play as one of the seven charter franchises of the professional National Basketball League of Canada. The franchise failed at the end of the 2016/17 season, to be immediately replaced by a new NBL franchise, the Moncton Magic, who played their inaugural season in 2017/18.[108] The Universite de Moncton has a number of active CIS university sports programs including hockey, soccer, and volleyball.[109] These teams are a part of the Canadian Interuniversity Sport program.[110]

| Club | Sport | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moncton Magic | Basketball | NBL Canada | Avenir Centre | 2017 | 1 – NBLC Championship 2019[111] |

| Moncton Wildcats | Ice hockey | QMJHL | Avenir Centre | 1996 | 2 – President's Cup (QMJHL) |

| Moncton Fisher Cats | Baseball | NBSBL | Kiwanis Park | 2015 | 1 – NBSBL Championship (2017)[112] |

| Moncton Mustangs | Football | MFL | Rocky Stone Field | 2004 | 5 – Maritime Bowl |

| Moncton Mavericks | Lacrosse | ECJLL (JR A) | Superior Propane Centre | 2006 | 1 (Jr.B 2008) |

| U de M Aigles Bleus | Ice hockey (M/F) Soccer (M/F) Volleyball (F) track and field (M/F) Cross country running (M/F) | AUS | Aréna Jean-Louis-Lévesque U de M CEPS Stade Moncton Stadium | 1964 | Men's Hockey – 11 (AUS), 4 (CIS) Women's Hockey – 1 (AUS) Women's Volleyball – 5 (AUS) Men's Athletics – 6 (AUS) Women's Athletics – 2 (AUS) |

| Crandall Chargers | Baseball (M) Soccer (M/F) Basketball (M/F) Cross country running (M/F) | ACAA CIBA | Various Campus Facilities | 1949 | 1 – CIBA Regional Championships |

Major events

Moncton has hosted many large sporting events. The 2006 Memorial Cup was held in Moncton with the hometown Moncton Wildcats losing in the championship final to rival Quebec Remparts.[113] Moncton hosted the Canadian Interuniversity Sports (CIS) Men's University Hockey Championship in 2007 and 2008.[114] The World Men's Curling Championship was held in Moncton in 2009; the second time this event has taken place in the city.

Moncton also hosted the 2010 IAAF World Junior Championships in Athletics. This was the largest sporting event ever held in Atlantic Canada, with athletes from over 170 countries in attendance. The new 10,000-seat capacity Moncton Stadium was built for this event on the Université de Moncton campus.[115] The construction of this new stadium led directly to Moncton being awarded a regular season neutral site CFL game between the Toronto Argonauts and the Edmonton Eskimos, which was held on September 26, 2010.[116] This was the first neutral site regular season game in the history of the Canadian Football League and was played before a capacity crowd of 20,750. Additional CFL regular season games were held in 2011 and 2013, and again on August 25, 2019.[117]

Moncton was one of only six Canadian cities chosen to host the 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup.

Major sporting events hosted by Moncton include:

- 1968 Canadian Junior Baseball Championships

- 1974 Canadian Figure Skating Championships

- 1975 Macdonald Lassies Championship

- 1975 Intercontinental Cup (baseball, co-hosted with Montreal)

- 1977 Skate Canada International

- 1978 CIS University Cup (hockey)

- 1980 World Men's Curling Championships

- 1982 World Short Track Speed Skating Championships

- 1982 CIS University Cup

- 1983 CIS University Cup

- 1984 Canadian Men's and Women's Broomball Championships

- 1985 Canadian Figure Skating Championships

- 1985 Labatt Brier (curling)

- 1992 Canadian Figure Skating Championships

- 1997 World Junior Baseball Championships

- 2000 Canadian Junior Curling Championships

- 2004 Canadian Senior Baseball Championships

- 2006 Memorial Cup (hockey)

- 2007 CIS University Cup

- 2008 CIS University Cup

- 2009 World Men's Curling Championship

- 2009 Fred Page Cup (hockey)

- 2010 IAAF World Junior Championships in Athletics

- 2010 CFL regular season neutral site game (Toronto and Edmonton)

- 2011 CFL regular season neutral site game (Hamilton and Calgary)

- 2012 Canadian Figure Skating Championships

- 2013 Canadian Track & Field Championships

- 2013 Football Canada Cup (national U18 football championship)

- 2013 CFL regular season neutral site game (Hamilton & Montreal)

- 2014 Canadian Track & Field Championships

- 2014 FIFA U20 Women's World Cup

- 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup

- 2017 Canadian U18 Curling Championships

- 2019 CFL regular season neutral site game (Toronto and Montreal)

- 2023 World Junior Ice Hockey Championships (Co-hosted with Halifax)

Government

The municipal government consists of a mayor and ten city councillors elected to four-year terms of office. The council is non-partisan with the mayor serving as the chairman, casting a ballot only in cases of a tie vote. There are four wards electing two councillors each with an additional two councillors selected at large by the general electorate. Day-to-day operation of the city is under the control of a City Manager.[118]

Moncton is in the federal riding of Moncton—Riverview—Dieppe. Portions of Dieppe are in the federal riding of Beauséjour, and portions of Riverview are in the riding of Fundy Royal. In the current federal parliament, two MPs from the metropolitan area belong to the Liberal party and one to the Conservative party.

| Year | Liberal | Conservative | New Democratic | Green | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 48% | 16,670 | 24% | 8.266 | 17% | 5,974 | 4% | 1,538 | |

| 2019 | 42% | 16,621 | 24% | 9,369 | 12% | 4,812 | 18% | 7,027 | |

| Year | PC | Liberal | Green | People's Allnc. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 43% | 13,210 | 33% | 10,105 | 16% | 5,112 | 6% | 1,720 | |

| 2018 | 32% | 9,983 | 44% | 13,600 | 10% | 3,064 | 3% | 1,034 | |

Military

Aside from locally formed militia units, the military did not have a significant presence in the Moncton area until the beginning of the Second World War. In 1940, a large military supply base (later known as CFB Moncton) was constructed on a railway spur line north of downtown next to the CNR shops. This base served as the main supply depot for the large wartime military establishment in the Maritimes.[121] In addition, two Commonwealth Air Training Plan bases were also built in the Moncton area during the war: No. 8 Service Flying Training School, RCAF, and No. 31 Personnel Depot, RAF. The RCAF also operated No. 5 Supply Depot in Moncton.[121] A naval listening station was also constructed in Coverdale (Riverview) in 1941 to help in coordinating radar activities in the North Atlantic.[121] Military flight training in the Moncton area terminated at the end of World War II and the naval listening station closed in 1971. CFB Moncton remained open to supply the maritime military establishment until just after the end of the Cold War.[121]

With the closure of CFB Moncton in the early 1990s, the military presence in Moncton has been significantly reduced.[122] The northern portion of the former base property has been turned over to the Canada Lands Corporation and is slowly being redeveloped.[123] The southern part of the former base remains an active DND property and is now termed the Moncton Garrison. It is affiliated with CFB Gagetown.[122] Resident components of the garrison include the 1 Engineer Support Unit (Regular force). The garrison also houses the 37 Canadian Brigade Group Headquarters (reserve force) and one of the 37 Brigades constituent units; the 8th Canadian Hussars (Princess Louise's), which is an armoured reconnaissance regiment.[122] 3 Area support unit Det Moncton, and 42 Canadian Forces Health Services Centre Det Moncton provide logistical support for the base.[122] In 2013, the last regular forces units left the Moncton base, but the reserve units remain active and Moncton remains the 37 Canadian Brigade Unit headquarters.

Infrastructure

Health facilities

There are two major regional referral and teaching hospitals in Moncton. The Moncton Hospital has approximately 381 inpatient beds[124] and is affiliated with Dalhousie University Medical School. It is home to the Northumberland family medicine residency training program and is a site for third and fourth year clinical training for medical students in the Dalhousie Medicine New Brunswick Training Program. The hospital hosts UNB degree programs in nursing and medical x-ray technology and professional internships in fields such as dietetics. Specialized medical services at the hospital include neurosurgery, peripheral and neuro-interventional radiology, vascular surgery, thoracic surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, orthopedics, trauma, burn unit, medical oncology, neonatal intensive care, and adolescent psychiatry. A$48 million expansion to the hospital was completed in 2009 and contains a new laboratory, ambulatory care centre, and provincial level one trauma centre.[125] A new oncology clinic was built at the hospital and opened in late 2014. The Moncton Hospital is managed by Horizon Health Network (formerly the South East Regional Health Authority).

.jpg.webp)

The Dr. Georges-L.-Dumont University Hospital Centre has about 302 beds[126] and hosts a medical training program through the local CFMNB and distant Université de Sherbrooke Medical School. There are also degree programs in nursing, medical x-ray technology, medical laboratory technology and inhalotherapy which are administered by Université de Moncton. Specialized medical services include medical oncology, radiation oncology, orthopedics, vascular surgery, and nephrology. A cardiac cath lab is being studied for the hospital and a new PET/CT scanner has been installed. A$75 million expansion for ambulatory care, expanded surgery suites, and medical training is currently under construction.[127] The hospital is also the location of the Atlantic Cancer Research Institute.[128] This hospital is managed by francophone Vitalité Health Network.

The internal working languages of the hospitals are English for the Moncton Hospital (Horizon Health Network) and French for the Dumont Hospital (Vitalité). However both health networks and their hospitals are required to provide services to the public in both official languages, in accordance with the New Brunswick Official Languages Act.[129]

Transportation

Air

.jpg.webp)

Moncton is served by the Greater Moncton Roméo LeBlanc International Airport (YQM). It was renamed for former Canadian Governor-General (and native son) Roméo LeBlanc in 2016. A new airport terminal with an international arrivals area was opened in 2002 by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. The GMIA handles about 677,000 passengers per year, making it the second busiest airport in the Maritimes in terms of passenger volume.[130] The GMIA is the 10th busiest airport in Canada in terms of freight. Regular scheduled destinations include Halifax, Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto. Scheduled service providers include Air Canada, Air Canada Rouge, Westjet and Porter Airlines. Seasonal direct air service is provided to destinations in Cuba, Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Florida, with operators including Sunwing Airlines, Air Transat, and Westjet.[131] FedEx, UPS, and Purolator all have their Atlantic Canadian air cargo bases at the facility. The GMIA is the home of the Moncton Flight College; the largest pilot training institution in Canada,[132] and is also the base for the regional RCMP air service, the New Brunswick Air Ambulance Service and the regional Transport Canada hangar and depot.

There is a second smaller aerodrome near Elmwood Drive. McEwen Airfield (CCG4) is a private airstrip used for general aviation. Skydive Moncton operates the province's only nationally certified sports parachute club out of this facility.[133]

The Moncton Area Control Centre is one of only seven regional air traffic control centres in Canada.[134] This centre monitors over 430,000 flights a year, 80% of which are either entering or leaving North American airspace.[134]

Highways

Moncton lies on Route 2 of the Trans-Canada Highway, which leads to Nova Scotia in the east and to Fredericton and Quebec in the west. Route 15 intersects Route 2 at the eastern outskirts of Moncton, heads northeast leading to Shediac and northern New Brunswick, Route 16 connects to route 15 at Shediac and leads to Strait Shores and Prince Edward Island. Route 1 intersects Route 2 approximately 15 kilometres (9 mi) west of the city and leads to Saint John and the U.S. border.[135] Wheeler Boulevard (Route 15) serves as an internal ring road, extending from the Petitcodiac River Causeway to Dieppe before exiting the city and heading for Shediac. Inside the city it is an expressway bounded at either end by traffic circles.[135]

Public transit

Greater Moncton is served by Codiac Transpo, which is operated by the City of Moncton. It operates 40 buses on 19 routes throughout Moncton, Dieppe, and Riverview.[136]

Maritime Bus provides intercity service to the region. Moncton is the largest hub in the system. All other major centres in New Brunswick, as well as Charlottetown, Halifax, and Truro are served out of the Moncton terminal.

Railways

Freight rail transportation in Moncton is provided by Canadian National Railway. Although the presence of the CNR in Moncton has diminished greatly since the 1970s, the railway still maintains a large classification yard and intermodal facility in the west end of the city, and the regional headquarters for Atlantic Canada is still located here as well. Passenger rail transportation is provided by Via Rail Canada, with their train the Ocean serving the Moncton railway station three days per week to Halifax and to Montreal, Quebec.[137] The downtown Via station has been refurbished and also serves as the terminal for the Maritime Bus intercity bus service.

Education

The South School Board administers 10 Francophone schools, including high schools École Mathieu-Martin and École L'Odyssée. The East School Board administers 25 Anglophone schools including Moncton, Harrison Trimble, Bernice MacNaughton, and Riverview high schools.

Post secondary education in Moncton:

- The Université de Moncton is a publicly funded provincial comprehensive university and is the largest francophone Canadian university outside of Quebec.

- Crandall University is a private undergraduate liberal arts university.[138]

- The University of New Brunswick has a satellite health sciences campus at Moncton Hospital offering degrees in nursing and medical X-ray technology.

- The Moncton campus of the New Brunswick Community College has 1,600 full-time students and also hundreds of part-time students.

- The Collège communautaire du Nouveau-Brunswick offers training in trades and technologies.

- Medavie HealthEd, a subsidiary of Medavie Health Services, is a Canadian Medical Association-accredited school providing training in primary and advanced care paramedicine, as well as the Advanced Emergent Care (AEC) program of the Department of National Defence (Canada).

- Eastern College offers programs in the areas of business and administration, art and design, health care, social sciences & justice, tourism & hospitality, and trades.

- Moncton Flight College is one of Canada's oldest and largest flight schools.[139]

- McKenzie College specializes in graphic design, digital media, and animation.

- The private Oulton College provides training in business, paramedical, dental sciences, pharmacy, veterinary, youth care and paralegal programs.

Media

Moncton's daily newspaper is the Times & Transcript, which has the highest circulation of any daily newspaper in New Brunswick.[140] More than 60 percent of city households subscribe daily, and more than 90 percent of Moncton residents read the Times & Transcript at least once a week. The city's other publications include L'Acadie Nouvelle, a French newspaper published in Caraquet in northern New Brunswick.

There are 17 broadcast radio stations in the city covering a variety of genres and interests, all on the FM dial or online streaming. Eleven of these stations are English and six are French.

Rogers Cable has its provincial headquarters and main production facilities in Moncton and broadcasts on two community channels, Cable 9 in French and Cable 10 in English. The French-language arm of the CBC, Radio-Canada, maintains its Atlantic Canadian headquarters in Moncton. There are three other broadcast television stations in Moncton and these represent all of the major national networks.

Notable people

Moncton has been the home of a number of notable people, including National Hockey League Hall of Famer and NHL scoring champion Gordie Drillon,[141] World and Olympic champion curler Russ Howard,[142] distinguished literary critic and theorist Northrop Frye,[143] former Governor-General of Canada Roméo LeBlanc,[144] and former Supreme Court Justice Ivan Cleveland Rand, developer of the Rand Formula and Canada's representative on the UNSCOP commission.[145] Trudy Mackay FRS, renowned quantitative geneticist, member of the Royal Society[146] and National Academy of Sciences,[147] and recipient of the prestigious Wolf Prize for agriculture[148] (2016), was born in Moncton.[149] Robb Wells, the actor who plays Ricky on the Showcase hit comedy Trailer Park Boys hails from Moncton,[150][151] along with Julie Doiron,[152][153] an indie rock musician, and Holly Dignard the actress who plays Nicole Miller on the CTV series Whistler.[154] Harry Currie, noted Canadian conductor, musician, educator, journalist and author was born in Moncton[155] and graduated from MHS. Antonine Maillet, a francophone author, recipient of the Order of Canada and the "Prix Goncourt", the highest honour in francophone literature, is also from Moncton.[156] France Daigle, another acclaimed Acadian novelist and playwright, was born and resides in Moncton, and is noted for her pioneering use of chiac in Acadian literature, was the recipient of the 2012 Governor General's Literary Prize in French Fiction, for her novel Pour Sûr (translated into English as "For Sure"). Canadian hockey star Sidney Crosby graduated from Harrison Trimble High School in Moncton.

Sister cities

- Lafayette, Louisiana, United States[157]

- North Bay, Ontario, Canada[158]

See also

References

Notes

- Statistic includes all persons that did not make up part of a visible minority or an indigenous identity.

- Statistic includes total responses of "Filipino" and "Southeast Asian" under visible minority section on census.

- Statistic includes total responses of "Chinese", "Korean", and "Japanese" under visible minority section on census.

- Statistic includes total responses of "West Asian" and "Arab" under visible minority section on census.

- Statistic includes total responses of "Visible minority, n.i.e." and "Multiple visible minorities" under visible minority section on census.

- LeBreton, Cathy (October 22, 2012). "Major employment forum held this week in Moncton". News 91.9. Rogers Communications. Archived from the original on February 8, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population Data table". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population Data table". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population Data table". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- "Moncton". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada.

- "Table 36-10-0468-01 Gross domestic product (GDP) at basic prices, by census metropolitan area (CMA) (x 1,000,000)". Statistics Canada. January 27, 2017. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- Morrison, Catherine (January 2023). "N.B.cities see major population growth". Telegraph-Journal. Daily Gleaner. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

Moncton saw the biggest percentage increase not only in New Brunswick but in urban centres of Canada

- "Moncton's motto Resurgo holds historic importance to city". CBC News – New Brunswick. June 13, 2014. Archived from the original on August 29, 2014. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- "Local Governments Establishment Regulation – Local Governance Act". Government of New Brunswick. October 12, 2022. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- "RSC 7 Southeast Regional Service Commission". Government of New Brunswick. January 31, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- Boudreau 12

- Boudreau 16

- Medjuck, Sheva (March 13, 2007). "Moncton". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- "Parks Canada – Fort Beauséjour – Fort Cumberland National Historic Site of Canada – Natural Wonders & Cultural Treasures – Cultural Heritage". Parks Canada. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- Larracey 30

- "Acadia, History of". Canadian Encyclopedia. March 13, 2007. Archived from the original on February 20, 2015. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- Larracey 32

- The German Origins of Charles Jones, aka Johann Carl Schantz, of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Monckton, New Brunswick Archived May 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine By Rick Crume, with genealogical research by Dawn Edlund, November 2008

- "The History of Moncton". Tourism Moncton. 2008. Archived from the original on January 15, 2009. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- Larracey 45

- Brown, George W. (1966). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto Press. p. 727. ISBN 0-8020-3142-0.

- Larracey 25

- "National Transcontinental Railway". The Canadian Encyclopedia. March 13, 2007. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- Larracey 28

- "Company Histories: Eaton's". Virtual Museum of Canada. Archived from the original on January 25, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- Larracey 46

- Larracey 52

- "Musée acadien de l'Université de Moncton – Canada –". virtualmuseum.ca. Archived from the original on 2 July 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- "University of Moncton". Government of New Brunswick. March 13, 2006. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- Larracey 62

- "Moncton". The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. March 13, 2001. Archived from the original on December 8, 2007. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- "CFB Gagetown Support Detachment Moncton". Department of National Defence. September 12, 2006. Archived from the original on March 17, 2004. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- Wickens, Barbara (October 27, 1997). "When cheaper is better". Maclean's. Vol. 110, no. 43. p. 10.

- "Turner and Drake newsletter: Spring 1994". Turner Drake & Partners Ltd. Archived from the original on July 17, 2007. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- "Organization internationale de la Francophonie: Choronologie" (PDF) (in French). Francophonie. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- "GMIA Home". Greater Moncton International Airport. Archived from the original on November 7, 2004. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- "Gunningsville Bridge opens to traffic (05/11/19)". Communications New Brunswick. November 19, 2005. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- "Moncton votes to become Canada's first bilingual city". CBC News. August 7, 2002. Archived from the original on October 16, 2006. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- "2006 Community Profiles". Statistics Canada. 2006. Archived from the original on December 8, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- "After 42 Years, a River Finally Runs Through it". 2010. Archived from the original on May 13, 2011. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- "Legion Magazine : The Tidal Bore". Legion Magazine. 2000. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- "Info on the Tidal bore in Moncton". Legion Magazine. March 13, 2007. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- "Tidal Bore Makes Waves". 2010. Archived from the original on May 1, 2010. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- "Moncton Climate data". Environment Canada, Climate of New Brunswick Report. March 13, 2007. Archived from the original on June 3, 2007. Retrieved July 3, 2007.

- "Nor'easters". Wheeling Jesuit University. 13 March 2007. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- "Global warming disaster as thousands of harp seal pups perish: Experts call for annual seal hunt to be cancelled". International Fund for Animal Welfare. Archived from the original on February 7, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- "Canadian Climate Normals 1971–2000, Moncton Airport". Environment Canada. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- "Monthly Record, Meteorological Observations in Canada". Environment Canada. 1935. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- "Moncton, NB". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. September 25, 2013. Archived from the original on May 17, 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for September 2010". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- "Daily Data report for March 2012". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- "Moncton A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on May 12, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- "September 2010". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- "October 2011". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- "March 2012". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- "Bell Aliant Tower". Canada's Historic Places. April 20, 2007. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 25, 2007.

- "Assumption Life and the Drop Zone Create Some Extreme Thrills". Assumption Life. August 31, 2006. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved May 4, 2008.

- "Blue Cross Centre". Fortis Inc. 20 April 2006. Archived from the original on 8 December 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- "Centennial Park". www.moncton.ca. 6 April 2008. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- "Community Parks". www.moncton.ca. 6 April 2008. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- Merlin 4

- "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions and census subdivisions (municipalities), New Brunswick". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- "Geographical hierarchy". Statistics Canada. January 19, 2009. Archived from the original on February 19, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 26, 2022). "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 27, 2021). "Census Profile, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (November 27, 2015). "NHS Profile". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (August 20, 2019). "2006 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (July 2, 2019). "2001 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population - Moncton, City (C) [Census subdivision], New Brunswick". February 9, 2022.

- "2011 Community Profiles". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2012. Archived from the original on February 12, 2015. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 26, 2022). "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- "Downtown Moncton at a Glance". DMCI. Archived from the original on April 14, 2010. Retrieved June 18, 2007.

- "nanoptix". nanoptix. Archived from the original on December 31, 2018. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- "TrustMe". TrustMe Security. Archived from the original on December 21, 2018. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- "The Greater Moncton Economy "Towards a Vision"" (PDF). greatermoncton.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2006. Retrieved 18 June 2007.

- "Selected trend data for Moncton (CMA), 2006, 2001 and 1996 censuses". Statistics Canada. June 2008. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- Holloway, Andy (November 2004). "The best cities for business in Canada". Canadian Business. Archived from the original on February 5, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- "Moncton ranked among most business-friendly cities, Times and Transcript May 9, 2007". Colliers International. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- "Colliers International (Atlantic) Inc. – Moncton". Colliers International. Archived from the original on April 27, 2006. Retrieved June 18, 2007.

- "TD Bank announces new banking services centre in Moncton". Archived from the original on May 26, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- "Irving Group Moncton". J.D. Irving Limited. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 18 June 2007.

- "Molson to establish small brewery in Moncton by 2007". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on December 13, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- "Gunningsville Bridge information". Government of New Brunswick. November 19, 2005. Archived from the original on July 23, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- "The operative word for Moncton during 2006 was "up"! Moncton for Business – Moncton en Affaires". Moncton for Business. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 18 June 2007.

- "Living in Greater Moncton" (PDF). City of Moncton. 15 July 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2008. Retrieved 26 June 2007.

- "Capitol History". Capitol Theater. March 13, 2007. Archived from the original on July 16, 2007. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- "Defining 'Culture' in Moncton". Here NB. January 29, 2009. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved January 30, 2009.

- O'Haver, Kimberly. "Atlantic Ballet Theatre of Canada". Pointe Magazine. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- "About The Aberdeen Cultural Centre (French)". Aberdeen Cultural Centre. Archived from the original on July 4, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- "Resurgo Place". Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- "Musée acadien | Campus de Moncton". www.umoncton.ca. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011.

- "Moncton Museum". April 13, 2008. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- Treitz Haus. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- "L'ONF en Acadie, 35 ans de création". National Film Board of Canada (in French). Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- "Frye Festival History". Frye Festival. March 13, 2006. Archived from the original on July 9, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- "Car star revs up auto show". Times and Transcript. March 13, 2005. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- "Seafood festival looks for best fried clams, fish cakes, chowder". Canadian Online Explorer. August 8, 2008. Retrieved January 27, 2009.

- "The Government of Canada Supports HubCap Comedy Festival". Department of Canadian Heritage. July 17, 2008. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved January 27, 2009.

- Mercure, Lili (July 31, 2019). "Notre-Dame-de-l'Assomption: une cathédrale numérique". Acadie Nouvelle. Archived from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- News 91.9. "Avenir Centre".

- "CEPS – Français". Universite de Moncton. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- Philip Drost (May 22, 2018). "Dieppe closes velodrome because of safety concerns". CBC News. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- "Facilities". Atlantic Cycling Centre. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- "Moncton wraps up Quebec series at home". The Globe and Mail. May 15, 2006. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- Harding, Gail. "Dieppe Commandos hockey franchise moving to Edmundston". CBC. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- "Moncton wins national senior baseball championship". CBC. August 28, 2006. Archived from the original on September 1, 2006. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- "Magic retire Miracles". June 22, 2017. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- "Aigles Bleus". University of Moncton. September 19, 2008. Archived from the original on November 7, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- "CIS Membership Directory". Canadian Interuniversity Sport. September 19, 2008. Archived from the original on June 15, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- "2019 NBLC Playoffs". National Basketball League of Canada. Archived from the original on November 28, 2019. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- "Fisher Cats Savour City's First Senior Baseball Championship in 12 Years". Moncton Times & Transcript. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "MasterCard Memorial Cup". Canadian Hockey League. Archived from the original on July 4, 2007. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- "2007 CIS Men's Hockey Championships". Canadian Interuniversity Sport. Archived from the original on April 7, 2007. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- "Moncton awarded 2010 IAAF World Junior Championships" (PDF). City of Moncton. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 28, 2007. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- "CFL's Touchdown Atlantic". Newswire.ca. July 30, 2010. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011.

- "LeBlanc: TD Atlantic bringing added hype to Maritime expansion effort". cfl.ca. August 23, 2019. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- "Moncton City Council (2004–2008)". City of Moncton. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- "Official Voting Results Raw Data (poll by poll results in Moncton)". Elections Canada. April 7, 2022. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- "Official Voting Results by polling station (poll by poll results in Moncton)". Elections NB. February 5, 2014. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- "Canadian Military History Page". Bruce Forsyth. March 13, 2007. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- "CFB Gagetown Support Detachment Moncton". Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces. March 13, 2007. Archived from the original on March 17, 2004. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- "CLC Corporate Plan 1999–2004" (PDF). Canada Lands Company. 13 March 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- "The Moncton Hospital". Horizon Health Network. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- "SERHA's Health: Taking a large step into the future" (PDF). SERHA. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 30, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- "Dr. Georges-L-Dumont Hospital Centre". Archived from the original on December 25, 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2017.

- "Georges Dumont Hospital to host new cardiac lab". CBC News. January 23, 2007. Archived from the original on December 8, 2007. Retrieved July 9, 2007.

- "R&D Facilities". New Brunswick. May 23, 2008. Archived from the original on November 22, 2008. Retrieved January 30, 2009.