Monoclea forsteri

Monoclea forsteri is one of the two species in the thallose liverwort family Monocleaceae. It is dioicous with the capsule dehiscing with a single longitudinal slit.[1] Endemic and widely distributed throughout New Zealand, it is also the country's largest thalloid liverwort.[2][1][3][4] Hooker described the species in 1820.[5][3] The holotype is in the British Museum.[6]

| Monoclea forsteri | |

|---|---|

| |

| Monoclea forsteri with sporophytes | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Marchantiophyta |

| Class: | Marchantiopsida |

| Order: | Marchantiales |

| Family: | Monocleaceae |

| Genus: | Monoclea |

| Species: | M. forsteri |

| Binomial name | |

| Monoclea forsteri | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Monoclea hookeri | |

Distribution and ecology

Monoclea forsteri is distributed throughout New Zealand, including the subantarctic Auckland Islands.[3][6] It is commonly found near streams but also throughout damp areas.[3] Plants are dioicous so local populations may be mixed, or purely male or female.[3] There is no difference in morphology when plants are found in different conditions, however, plants that are subject to submergence are often sterile.[3]

Mycorrhiza

Specimens grown in a greenhouse in 1902 showed branching mycorrhizal hyphae in a defined mycorrhizal zone consisting of two to four cell layers.[7] Further studies have identified endophytic fungi related to Acaulospora associated with Monoclea forsteri.[8]

Morphology

Gametophyte

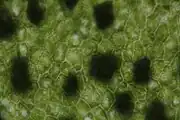

Thallus is dark green at maximum 5 cm wide and 20 cm long with dichotomous branching present.[2] The middle is up to ten cells thick whereas the margins can be one to four and there is little differentiation in cell size.[2] Rhizoids are smooth, and present on the ventral surface with those at the central portion of the thallus growing into the soil whereas ones at the margins either growing into the soil or lying parallel to the thallus.[2][9] Thallus is without any air chambers, air pores and ventral scales.[9] The thallus growth is from a wedge-shaped apical cell which has four cutting faces.[2] Complex oil bodies are one per cell and large and contain chloroplasts.[6] Plants dioicous. Chromosomes n = 9.[10]

Male plant's antheridial receptors form clumps visible both ventrally and dorsally.[2] Antheridial receptacles are orbicular with margins bluntly crenulate or entire, hairs produced below the margins may be numerous or lacking.[6] Each receptor has between 25 and 50 antheridia.[2]

Female plants have flask-shaped cavities which form a bulge on the ventral surface and are visible as small pores on the dorsal surface. These cavities form at the mid-thallus. The egg at fertilisation is 125 microns in diameter.[2] Both archegonia and antheridia mature throughout the year.[2]

Sporophyte

Several sporophytes can be produced from one receptacle. Setae are positively phototropic and are between 32 and 40 cells in height.[2][6] The calyptra is colourless and fleshly. The capsule when ripe is oval and up to 5 mm long and 1 mm wide. It dehiscing by a single longitudinal slit on the ventral surface. Spores are released by twisting of the elaters that are mixed with the spores.[2]

Unusual features

Monoclea forsteri has a myriad of features which contributed to confusion in taxonomic placement or are uncommon in bryophytes. Monoclea is also one of the few genera in the Marchantiales that lack air pores and internal chambers.[9] The oil bodies are more similar to those of the Treubiales than those of the Marchantiales.[6] Often several sporophytes develop from a single receptacle and their capsules dehisce with a single longitudinal slit.[1] The setae have a period of rapid extension between 24 and 48 hours.[1] The inner and radial jacket and capsule wall cells have a reticulate thickening pattern.[1] The archegonium when fully developed has a large number of neck canal cells.[1]

Chemistry

The major constituents of Monoclea forsteri chemistry are a single terpenoid, Lunularic acid and three structural types of flavonoids. Bisbibenzyls and riccardin are recorded as minor constituents.[6][4] M. forsteri is considered to be poor in secondary compounds.[6]

Taxonomic history

Monoclea forsteri was described solely from female plants by William J. Hooker from specimens collected by G.E. Forster in 1773–1774.[1] Males, due to their antheridial anatomy, were not recognised for another 40 years and were originally described as Dumortiera dilatata.[11] Monoclea was initially placed in the Jungermanniales based on the female characters,[5] but was then shifted between the Metzgeriales and the Marchantiales, and was even placed in its own order, the Monocleales by Schuster in 1963.[12]

There has been confusion about its relationship to the South and Central American species, Monoclea gottschei, but even the identity of Monoclea in New Zealand was uncertain. William Colenso described a new species in 1883, M. hookeri, which was eventually synonymised in 1972 by Hamlin.[3] Monoclea gottschei was described in 1886 from South America.[13] Ella Campbell in 1987 believed M. forsteri and M. gottschei species to be one entity based on male plant morphological similarities and in plant comparisons grown in Proskauer's laboratory.[3]

Gradstein et al. in 1992 recognised Monoclea forsteri and M. gottschei as being distinct due to sporophyte character and chemical differences, but did not do phylogenetic work.[6]

Long-standing uncertainty over the placement of Monoclea in Metzgeriales, Marchantiales, or its own order was reached with DNA work.[14][9][15] These placed it in the order Marchantiales in the family Monocleaceae. Further work by Forrest et al. in 2006 showed it was sister to Dumortiera.[16]

Etymology

Monoclea: from the Greek, μόνος, meaning single, and the Greek, κλειω, meaning to shut. These refer to the capsule splitting down one side to release the spores. forsteri: presumably after G.E. Forster, the original collector.

Monoclea forsteri with sporophytes.

Monoclea forsteri with sporophytes. Monoclea forsteri with antheridial receptors.

Monoclea forsteri with antheridial receptors. Monoclea forsteri cells.

Monoclea forsteri cells. Emergent sporophytes of Monoclea forsteri.

Emergent sporophytes of Monoclea forsteri. Multiple sporophytes of Monoclea forsteri from one receptical.

Multiple sporophytes of Monoclea forsteri from one receptical.

References

- Campbell, E. O. (1984). "Looking at Monoclea again". Journal of the Hattori Botanical Laboratory. 55: 315–319.

- Campbell, E. O. (1953). "The structure and development of Monoclea forsteri, Hook". American Bryological and Lichenological Society. 82: 237–248.

- Campbell, E. O. (1987). "Monoclea (Hepaticae); distribution and number of species". American Bryological and Lichenological Society. 90 (4): 371–373.

- Toyota, M.; Nagashima, F.; Asakawa, Y. (1988). "Fatty acids and cyclic bis(bibenzyls) from the New Zealand liverwort Monoclea forsteri". Phytochemistry. 27 (8): 2603–2608. Bibcode:1988PChem..27.2603T. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(88)87032-8.

- Hooker, W. J. (1819–1820). Musci exotici: containing figures and descriptions of new or little known foreign mosses and other cryptogamic subjects. London: Longman, Hurst, Reese, Orme and Brown.

- Gradstein, S. R.; Klein, R.; Kraut, L.; Meus, R.; Spörle, J.; Becker, H. (1992). "Phytochemical and morphological support for the existence of two species in Monoclea (Hepaticae)". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 180 (1–2): 115–135. doi:10.1007/BF00940401. S2CID 8078744.

- Cavers, F. (1903). "On saprophytism and mycorhiza in Hepaticae". New Phytologist. 2 (2): 30–35. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1903.tb05804.x.

- Ligrone, R; Carafa, A; Lumini, E; Bianciotto, V; Bonfante, P; Duckett, JG (2007). "Glomeromycotean associations in liverworts: a molecular, cellular, and taxonomic analysis". American Journal of Botany. 94 (11): 1756–1777. doi:10.3732/ajb.94.11.1756. PMID 21636371.

- Crandall-Stotler, B; Stotler, R. E.; Long, D. G. (2009). "Phylogeny and classification of the Marchantiophyta". Edinburgh Journal of Botany. 66 (1): 155–198. doi:10.1017/S0960428609005393.

- Proskauer, J. (1951). "Notes on Hepaticae II". Bryologist. 54 (4): 243–266. doi:10.1639/0007-2745(1951)54[243:NOHI]2.0.CO;2.

- Johnson, D. S. (1904). "The development and relationships of Monoclea". Botanical Gazette. 38 (3): 185–205. doi:10.1086/328540. S2CID 84884919.

- Schuster, R. M. (1963). "Studies on antipodal Hepaticae. Annotated keys to the genera of antipodal Hepaticae with special reference to New Zealand and Tasmania". Journal of the Hattori Botanical Laboratory. 26: 185–309.

- Gradstein, S. R. (2017). "Revised typification of Monoclea gottschei Lindb. (Marchantiophyta: Monocleaceae)". Journal of Bryology. 39 (4): 388–389. doi:10.1080/03736687.2017.1365219. S2CID 89732734.

- Boisselier-Dubayle, M. C.; Lambourdière, J.; Bischler, H. (2002). "Molecular phylogenies support multiple morphological reductions in the liverwort subclass Marchantiidae (Bryophyta)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 24 (1): 166–77. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00201-4. PMID 12128029.

- He-Nygrén, X.; Juslén, A.; Ahonen, I.; Glenny, D.; Piippo, S. (2006). "Illuminating the evolutionary history of liverworts (Marchantiophyta) – towards a natural classification". Cladistics. 22 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2006.00089.x. PMID 34892891. S2CID 86082381.

- Forrest, L. L.; David, C. E.; Long, D. G.; Crandall-Stotler, B. G.; Clark, A.; Hollingsworth, M. L. (2006). "Unraveling the evolutionary history of the liverworts (Marchantiophyta): multiple taxa, genomes and analyses". The Bryologist. 109 (6): 303–334. doi:10.1639/0007-2745(2006)109[303:UTEHOT]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85912159.