Monsieur Vénus

Monsieur Vénus (French pronunciation: [məsjø venys]) is a novel written by the French symbolist and decadent writer Rachilde (née Marguerite Eymery). Initially published in 1884, it was her second novel and is considered her breakthrough work. Because of its highly erotic content, it was the subject of legal controversy and general scandal, bringing Rachilde into the public eye.[1][2]

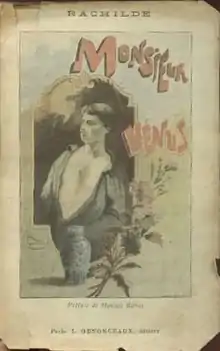

First French edition | |

| Author | Rachilde |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Genre | Decadent |

| Published | 1884 (Auguste Brancart, Belgium) 1889 (Brossier, France) |

Published in English | 1929 (Covici-Friede) |

| ISBN | 978-2-080-60969-4 (Flammarion), ISBN 978-0-873-52929-7 (Modern Language Association of America) |

The novel tells the story of French noblewoman Raoule de Vénérande and her pursuit of sexual pleasure while creating a new and more satisfying identity for herself. In order to escape the ennui and malaise of her tradition-bound upper class existence, she must subvert and transcend social class, gender roles, and sexual morality.[3][4]

History of the work

Rachilde was often flexible with biographical information; her account of writing Monsieur Vénus is no exception. According to Maurice Barrès, she wrote the book when she was still a virgin, not yet twenty years old (that is, before 1880). Rachilde variously reported writing it while in hysterical paralysis after the poet Catulle Mendès rejected her amorous overtures; writing it as catharsis for memories of her mother's abuse of her father; and writing it simply to create a scandal and make a name for herself.[3][4]

Whatever the circumstances in which it was written, the book was first released in 1884 by Belgian publisher Auguste Brancart with the dedication, "We dedicate this book to physical beauty," and a warning that any woman might secretly harbor the same desires as the depraved heroine of Monsieur Vénus. As was common at the time, the novel was serialized prior to its publication in one volume.[5][4]

The first edition was attributed to Rachilde and a co-author credited as "F. T.", supposedly a young man named Francis Talman who appears to have written nothing else before or since. It has been suggested that "Talman" was created to take the blame for the obscenity of the novel, much as Rachilde had once tried to convince her parents that earlier obscene content in her work was the fault of a Swedish ghost, "Rachilde."[5][6]

Three printings of the first edition were issued. The second and third printings were based on a revised first edition that changed the front matter and removed some content from the novel itself. Although not much was taken out in terms of overall word count, the effect of the changes was to soften some of the obscenity and may have represented an unsuccessful attempt at forestalling legal prosecution.[4][7]

The first French edition was published in 1889. Editor Felix Brossier opened the book by asserting that Rachilde was the sole author of Monsieur Vénus, explaining that some material from an unnamed collaborator had been removed. (In addition to maintaining the earlier revisions, further passages were cut, described by Rachilde as Talman's contributions.) Brossier went on to say that this edited version of the novel was literature, and had nothing in common with the sort of erotica that was "published and sold clandestinely."[8] Maurice Barrès also lent credibility to the publication with a lengthy preface in which he praised the author and prepared readers for what they were about to experience. The effect was to help legitimize the book for a French public both curious and apprehensive about this banned Belgian novel.[9][5]

This 1889 edition of the book was dedicated by Rachilde to Léo d'Orfer (née Marius Pouget), a former lover.[10][7] It was the basis for all subsequent editions and translations until the original first edition text was recovered for Monsieur Vénus: roman matérialiste (2004).[11]

Main characters

The following is a brief list of some of the characters most important to the story.[10][12][13]

- Raoule de Vénérande, a noble woman and artist, disaffected with her life and trying to create a more satisfying identity for herself.

- Jacques Silvert, a poor florist, the object of Raoule's desires and manipulations.

- Marie Silvert, the sister of Jacques and a prostitute, the feminine opposite of Raoule.

- Baron de Raittolbe, a suitor of Raoule and a soldier, the masculine opposite of Jacques.

- Ermengarde (1st Edition) / Élisabeth (French Edition), Raoule's aunt, the voice of the conservative cultural establishment.

Plot summary

Noblewoman Raoule de Vénérande becomes bored with her life and her usual suitors. She begins a relationship with an underprivileged florist named Jacques Silvert, paying him for his favors. Through a process of escalating humiliation, she transforms her lover from a weakly androgynous figure into a feminized one.

One of Raoule's suitors is Baron de Raittolbe, an ex-hussar officer. Raoule further flouts the rules of her social class by rejecting Raittolbe and marrying Silvert, sometimes referred to as her husband but positioned more as her wife. When a furious de Raittolbe beats Silvert, Raoule begins to abuse her spouse even more flagrantly. The spurned de Raittolbe takes to enjoying the companionship of Marie, Silvert's sister, who is a prostitute.

Silvert soon begins trying to seduce de Raittolbe himself. Jealous and frustrated that her project to create a perfect lover has failed, Raoule provokes de Raittolbe into responding by challenging Silvert to a duel. Most of their acquaintances do not understand why the duel is taking place, nor how Raoule encouraged its escalation from "to the blood" to "to the death." De Raittolbe wins the duel, killing Silvert.

Raoule does not grieve in the expected way. Not long after, she creates a wax dummy version of Silvert with real hair, teeth, and fingernails from a corpse (presumably Silvert's). In the closing passage of the novel, Raoule puts the grisly mannequin in a shrine and gazes upon it nightly, dressed in mourning clothes, sometimes as a woman and sometimes as a man. Each night she embraces the dummy and kisses its lips, which are mechanically animated to kiss her back.[14][3][5][10]

Major themes

The title of the book predicts some of its themes. While "Venus" establishes its erotic tone, the combination of the masculine "Monsieur" with the name of the female goddess suggests the gender subversion that dominates the story. The title also recalls the use in eighteenth century anatomy classes of wax female dummies called anatomical Venuses, anticipating the novel's ending.[3]

One major theme dominates all the others of the novel. Raoule is not looking for an escape. She is not ultimately looking for sexual pleasure. She is not even looking to "discover" herself. Instead, her quest is to create a new identity, better and more satisfying than the dreary and oppressive social role into which she was born.[5]

Social Class

It is no accident that bored and stifled Raoule de Vénérande is a member of the upper class, which represented the height of banal conformity for decadent writers. The hysteria that appears to drive her is the perfect excuse for her to escape the constraining traditions of her social class. Not only does she have an affair with a lower class man, she pays him for his favors, making him not her mistress but her gigolo. When she marries him, she is not only marrying outside her class, but is in effect marrying a prostitute.[3][15][5]

Importantly, Raoule does not subvert her social class in the modern way. She follows the model set forth by the decadents: not forsaking her wealth and privilege, but using them to her advantage and in defiance of the traditions that gave her that position in the first place. She does not pursue freedom as a starving artist; she claims freedom by transforming herself into a dandy.[16]

Gender Roles

The subversion of gender roles in Monsieur Vénus is twofold. First, there is the basic gender role reversal that can be observed in the power dynamics of the relationship between Raoule and Silvert. Beyond the act of cross-dressing, Raoule takes on traditionally masculine roles: she pursues the object of her desire and commands the obedience of her lover. She is also his abuser, and a better abuser than the man who had first beaten her lover, essentially asserting herself as a masculine figure. Similarly, in the end, she turns de Raittolbe into her hired assassin, once again proving herself the better man.[5][16]

Second, there is a deeper exploration of gender identity. Raoule sees Silvert as an androgynous figure with some feminine characteristics which she then amplifies. In one sense, through her merciless abuse, she helps him find a more secure gender identity for himself. At times he calls himself "Marie," his sister's name. By the same process, Raoule subverts her own gender; at one point Silvert begs her to just be a man. At the conclusion of the novel, Raoule appears to have no single gender identity, sometimes appearing as feminine and at other times as masculine.[3]

Sexuality

Her contemporary and friend Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly once remarked of Rachilde, "A pornographer, yes, she is, but such a distinguished one!"[4][6] Raoule does not feminize Jacques because she is attracted to women. She has no interest in Marie and she denies being a lesbian to de Raittolbe. She feminizes Jacques because she is using sexuality as an escape from ennui and a tool for shaping her identity. In pursuit of those goals, she explores and takes pleasure in cross-dressing, humiliation, sadomasochism and something that falls somewhere between Pygmalionism and necrophilia.[4][3][13]

Illusion and the Impossible Ideal

Throughout the novel Raoule demonstrates a willingness to push things further and further in pursuit of an ideal experience that she realizes is impossible. In the end, she turns to illusion and artifice and the force of her own will, since reality fails to comply with her wishes.[3][5] In this, she is joined by others in the Decadent Movement. In his Against Nature, Joris-Karl Huysmans suggested that human creations are more beautiful than natural ones, and also that the line between dream and waking reality depends simply on an act of human will.[17] Later, the Czech decadent Arthur Breisky would assert the priority of beautiful illusion over reality.[18] That is the context in which Rachilde's Raoule completes her transformation of Silvert by supplanting him with something of her own making, based on him, but improved through her creativity.[3]

Controversy and changes

The Belgian authorities were aggressive in pursuing legal action against Monsieur Vénus. A trial was held on charges of pornography. The author of the book was found guilty in absentia; the court ordered fines and two years of prison time. Belgian officials confiscated and destroyed every copy of the book they could find. While there is little question that the book qualified as obscene under existing statutes, Brancart the publisher was already on their radar for a number of reasons, a situation that likely contributed to the speed and thoroughness of their response. For her part, Rachilde simply avoided returning to Belgium and thereby escaped her sentence. French authorities began to monitor her, however, so Brancart hid most of her personal copies of the book, though no further legal action was taken against her.[2][4]

The revised first edition may have been an attempt to forestall what happened in Belgium, but it is believed that books from all three of the Brancart printings were destroyed. Nevertheless, the changes did soften certain kinds of obscenity. The revisions removed a description of Raoule experiencing an orgasm as she daydreamed about Silvert (Chapter 2) and abbreviated the moment of implied necrophilia. In the original, after describing how Raoule would kiss the mannequin and its mechanisms would allow it to kiss her back, the text continued by saying it also opened its thighs ("en meme temps quil fait s'ecarter les cuisses").[7][4][11]

When the 1889 French edition was put together, the rest of the so-called Talman material was removed, primarily the original Chapter 7. The focus of that chapter was very specifically on gender and the struggle for authority between the two sexes. The excised chapter describes Raoule as establishing the formula by which women could destroy men: using sexual pleasure to control them and rob them of their masculinity.[5][12][10]

It is worth noting that, contrary to some reports, that chapter was still present in the 1885 Brancart printing of the revised first edition and so was not subject to the original Belgian censorship of the novel. It was not removed until the Brossiers edition published in 1889, the year Rachilde married Alfred Vallette, who had always hated that material.[5][12][10]

In fact, the message of that chapter may have been reinforced in the 1885 printing by the quotation chosen for its cover: "To almost be a woman is a good way to defeat a woman." The quotation is from Catulle Mendès's "Mademoiselle Zuleika," which describes a man's realization that the only way to resist a woman's natural authority through her sexual appeal was to become more feminine himself in his flirtations and his vanity.[12][19]

Another alteration between the 1885 printing and the 1889 French edition concerns the name of Raoule's aunt, which was changed from Ermengarde to Elizabeth.[12][10]

Reception and influence

Beyond the legal problems in Belgium, the initial reception seems to have been a mixture of titillation at the erotic content, fascination with the scandal, and amusement at the fact that this darkly sexual fantasy was from the mind of a young woman who was only twenty-four years old at the time of initial publication and reportedly not yet twenty when she wrote it. Even among Rachilde's friends and supporters, there was a struggle to offer praise without either a wink or a snicker.

Monsieur Vénus was the occasion for Paul Verlaine's remark to Rachilde, "Ah! My dear child, if you've invented an extra vice, you'll be a benefactor of humanity!" In his preface to the 1889 Brossiers edition, Maurice Barrès described Monsieur Vénus as depraved, perverse, and nasty. He referred to it as a "sensual and mystical frenzy" and the appalling but exciting dream of a young virgin who suffered from the same hysteria as her main character.[9][20][21][5][4]

Even so, it was certainly Monsieur Vénus and its attendant scandal that consolidated Rachilde's position in the Parisian literary scene. Even a winking connection between Monsieur Vénus and the work of Charles Baudelaire was enough at the time to give Rachilde credibility within avant-garde circles.[5]

Oscar Wilde read the book while staying in France in 1889. Not only was he a fan, it is believed he drew inspiration from the novel for his own work, paying it tribute by naming the book that ensnares Dorian Gray Le Secret de Raoul.[22][4] Monsier Vénus is also credited with paving the way for other, less extreme, and ultimately more successful writers such as Colette to explore gender and the complexities of sexuality in their own work.[23]

Further reading

- Monsieur Vénus by Rachilde (Revised 1st Edition - via Google Books)

- Monsieur Vénus by Rachilde (1889 Edition - via Gutenberg Project)

- Maternal Fictions: Stendhal, Sand, Rachilde and Bataille by Maryline Lukacher

- Monsieur Vénus: A critique of gender roles by Melanie Hawthorn (published in Nineteenth Century French Studies)

References

- Holmes, D. (2001) Rachilde: Decadence, gender and the woman writer, Oxford and New York: Berg, p. 171.

- Hawthorne, Melanie C. and Liz Constable (2004) Monsieur Vénus: roman matérialiste, New York: Modern Language Association of America, p. xiv

- Lukacher, Maryline (1994). Maternal Fictions: Stendhal, Sand, Rachilde, and Bataille. Duke University – via Google Books.

- Hawthorne, Melanie C. (2001). Rachilde and French Women's Authorship: From Decadence to Modernism. University of Nebraska.

- Mesch, Rachel (2006). The Hysteric's Revenge: French Women Writers at the Fin de Siècle. Vanderbilt University.

- Gounaridou, Kiki; Lively, Frazer (1996). Kelly, Katherine E. (ed.). "Rachilde (Marguertie Eymery) The Crystal Spider". Modern Drama by Women, 1880s - 1930s.

- Finn, Michael (2009). Hysteria, Hypnotism, the Spirits, and Pornography: Fin-de-siècle Cultural Discourses in the Decadent Rachilde. University of Delaware.

- Brossier, Felix; Rachilde (1889). "Editor's Note". Monsieur Vénus – via Gutenberg Project.

- Barrès, Maurice; Madame Rachilde (1889). "Complications d'Amour". Monsieur Venus: Preface – via Gutenberg Project.

- Rachilde (1889). Monsieur Vénus. Paris – via Gutenberg Project.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hawthorne, Melanie C. and Liz Constable (2004) Monsieur Vénus: roman matérialiste, New York: Modern Language Association of America, p. xli

- Rachilde (1885). Monsieur Vénus: roman matérialiste. Brussels: Brancart.

- Nuila, Ennio A. (2013). Utopia of equality in Monsieur Vénus: Roman Matérialiste: Transgressing Gender Lines or Transgressing Social lines. University of Tennessee Knoxville.

- Holmes, D. (2001) Rachilde: Decadence, gender and the woman writer, Oxford and New York: Berg, pp. 3, 117, 120.

- Wilson, Steven (2015). "The Quest for Fictionality: Prostitution and Metatextuality in Rachilde's Monsieur Vénus". Modern Languages Open. doi:10.3828/mlo.v0i0.20.

- Starik, Marina (2012). Morphologies of Becoming: Posthuman Dandies in Fin-de-Siècle France (Ph.D. Dissertation). University of Pittsburgh.

- Huysmans, Joris-Karl (1922). Against the Grain. Lieber & Lewis – via Project Gutenberg.

- Bugge, Peter (2006). "Naked Masks: Arthur Breisky or How to Be a Czech Decadent". Word and Sense: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Theory and Criticism in Czech Studies. Retrieved 19 February 2017 – via Word and Sense website.

- Mendès, Catulle (1882). Les monstres parisiens. Paris: E. Dentu.

- Classen, Constance (2002). The Colour of Angels: Cosmology, Gender and the Aesthetic Imagination. Routledge.

- Bruzelius, Margaret (1993). ""En el profundo espejo del deseo": Delmira Agustini, Rachilde, and the Vampire". Revista Hispánica Moderna. 46: 51–64.

- Wilde, Oscar (2011). The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Version. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Harvard University.

- Jouve, Nicole Ward (1987). Colette. Indiana University.