Parc Montsouris

Parc Montsouris is a public park situated in southern Paris, France. Located in the 14th arrondissement, it was officially inaugurated in 1875 after an early opening in 1869.

| Parc Montsouris | |

|---|---|

Alley in Parc Montsouris | |

| Type | Urban park |

| Location | 14th arrondissement, Paris |

| Coordinates | 48°49′20″N 2°20′18″E |

| Area | 38 acres (15 ha) |

| Created | 2 October 1875 |

| Operated by | Direction des Espaces Verts et de l'Environnement (DEVE) |

| Status | Open all year |

| Public transit access | Located near the RER station Cité Universitaire |

Parc Montsouris is one of the four large urban public parks, along with the Bois de Boulogne, the Bois de Vincennes and the Parc des Buttes Chaumont, created by Emperor Napoleon III and his prefect of the Seine, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, at each of the cardinal points of the compass around the city, in order to provide green space and recreation for the rapidly growing population of Paris.[1] The park is 15.5 hectares in area, designed as an English landscape garden by Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand.[2]

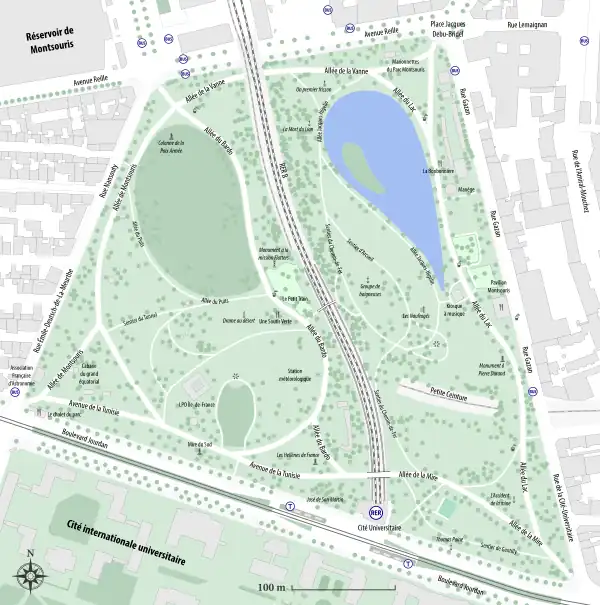

The park contains a lake, a cascade, wide sloping lawns, as well as many notable varieties of trees, shrubs and flowers. It is also home to a meteorology station, a cafe and a guignol theatre. The roads of the park are popular with joggers on weekends. Parc Montsouris is bounded to the south by Boulevard Jourdan and the Cité Internationale Universitaire de Paris (CIUP), to the north by Avenue Reille, to the east by Rue Gazan and the Rue de la Cité Universitaire and to the west by Rue Nansouty and Rue Émile Deutsch-de-la-Meurthe. Cité Universitaire station on RER B is located in the southern part of Parc Montsouris, where it connects to Île-de-France tramway Line 3a.

Etymology

According to the official website of the Park and other sources, the name of the park came from an old windmill, called the Moulin de Moque-Souris, which in the 18th century stood not far from the park site at the crossroads of rue d'Alesia and rue de la Tomb-Issoire.[3][4] Moque-Souris ("mocks-the-mice") was a common name for windmills in France at the time; it was a facetious name, suggesting that the miller dared the mice to find any grain inside. The name over time changed from moque-souris to Montsouris.[5]

Another possible origin of 'Montsouris' is common with the name of a former principal roadway, today's rue de la Tombe Issoire: after leaving the city to the south, it passed through a Roman-era cemetery that had fallen into disuse from the 4th century,[6] and it may have been one these abandoned tombs that an influential 13th-century writer declared to be the burial place of "Ysoré", a defeated giant of popular legend.[7] No matter the veracity of the story, many of the area's landmarks had taken the 'tombe Issoire' name by the 18th century,[8] and if 'Issoire' emerged from 'Ysoré', 'Montsouris' could be a 'mont Ysoré' that evolved over time.[9]

History

Inauguration and early years

The park was built by Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand, the engineer who headed the service of promenades and plantations created by Georges-Eugène Haussmann, with the assistance of city architect Gabriel Davioud and horticulturist Jean-Pierre Barillet-Deschamps. This was the team which together made the Bois de Boulogne, the Bois de Vincennes, and the other great landscape parks of the Second Empire. The project was decided in 1865, but construction did not actually begin until 1867, because of the long negotiations needed to buy the parcels of land needed for the park. The purpose of the park, according to Alphand, was "to bring life and movement to the center of a quarter until then left to isolation and abandon. " [10]

Unlike the Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes, the site for the future park did not have any trees or other vegetation. It was largely occupied by a large stone quarry, and to make the work more complicated, it was above a network of tunnels of abandoned mines, which were filled with human skeletons. These tunnels were part of the ossuary of Paris, popularly known as the catacombs of Paris, where the remains of some six million Parisians had been moved at the end of the 18th century. Before construction of the park could begin, some eight hundred skeletons were removed from the tunnels. The work was also complicated by the track of the railroad line which circled Paris, which passed directly through the site.

Despite these difficulties, the work went ahead briskly. A one-hectare artificial lake was dug, fed by an artificial stream that passed over an artificial cascade made of rocks and cement. Stairways were constructed up the hills, with rustic-looking railings made of cement formed to resemble logs. Winding roads and paths were built throughout the park. Davioud designed and built picturesque gatehouses, pavilions, a theatre, bandstand and a cafe to fit into the landscape. Barillet-Deschamps planted hundreds of trees and bushes, and laid out sloping lawns and flowerbeds. Every feature of the park was designed to create an idealized natural landscape, with space for both relaxation and recreation, which could be enjoyed by all classes of Parisians. The park was officially dedicated in 1869, but work on the park continued until 1878.[11]

According to a park legend, on the day of the park official opening someone made a mistake with the plumbing, and the water in the artificial lake drained away in a single day. According to the legend, the park engineer was so distraught that he committed suicide. It is recorded that the lake did in fact drain accidentally in one day in 1878, but there is no record of a suicide.[12]

During the 1871 Paris Commune, the park was the site of a military encampment, and witnessed fighting between the army and the Communards. In October 1897, the park was the setting of secret meetings between some of the figures involved in the Dreyfus Affair, including Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy and Max von Schwartzkoppen.

During World War II, a French soldier, Pierre Durand, was killed by a bomb in the park. A small monument near the lake remembers this event. In 1942, during the German occupation, one of the main monuments of the park, an 1893 allegorical statue of the French Revolution by sculptor Auguste Paris, was taken away and melted down for its bronze.

For many decades the most famous structure in the park was the Palais du Bardo, a reduced-size replica of the palace of the Bey of Tunis, made of wood and stucco, which was originally made for the Paris Universal Exposition of 1867. It was relocated to the park by park architect Gabriel Davioud, and placed at the highest point in the park (75 meters above sea level) which is also the highest point in the part of Paris on the left bank of the Seine. For many years it was the home of the meteorological station in the park, but the structure, designed to be temporary, began to crumble. The station moved to a new building, and the Palais suffered from decay and vandalism. In 1991 the ruins were destroyed by a fire.[13]

The Palais du Bardo, a reduced-size replica of the Palace of the Bey of Tunis, was a landmark of the park until it burned down in 1991.

The Palais du Bardo, a reduced-size replica of the Palace of the Bey of Tunis, was a landmark of the park until it burned down in 1991. The abandoned track of the Petite Ceinture railway line passes through Parc Montsouris. From 1852 to 1934, it ran inside the old city fortifications, and connected the five main railroad stations of Paris.

The abandoned track of the Petite Ceinture railway line passes through Parc Montsouris. From 1852 to 1934, it ran inside the old city fortifications, and connected the five main railroad stations of Paris.

Meridian of Paris

A stone monument in the park indicates the location of the Meridian of Paris, an imaginary line that passes from north to south through the center of Paris. This line, first defined by French astronomers in 1667, was used as the zero point for longitude on all French maps until 1884, when France agreed, reluctantly, to use longitudes measured from Greenwich Observatory near London instead of Paris.

The stone was originally located in the garden of the Paris Observatory, directly north of the park. The inscription shows it was first put in place in 1806 during the time of the Emperor Napoleon I, though his name was scratched off after the Restoration of the French monarchy. Today it is not exactly on the line of the Paris Meridian, but is about seventy meters east.

The stone which originally marked the Meridian of Paris, the beginning point for measuring longitude for all French maps until 1884.

The stone which originally marked the Meridian of Paris, the beginning point for measuring longitude for all French maps until 1884. The inscription on the stone marking the Paris Meridian, made in 1806, and originally placed in the garden of the Paris Observatory. The name of the Emperor Napoleon was erased from the monument after the Restoration of the Monarchy.

The inscription on the stone marking the Paris Meridian, made in 1806, and originally placed in the garden of the Paris Observatory. The name of the Emperor Napoleon was erased from the monument after the Restoration of the Monarchy.

Trees, plants and wildlife

The main In the lower section of the park, an island in the middle of a tiny lake provides sanctuary to forty species of wild ducks, geese, herons, and other migratory birds. Some turtles imported from Florida, regularly sunbathe on the lake's stony shores.

Common trees in the park include:

- Horse-Chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum)

- Common Yew (Taxus baccata)

- Cedar (Cedrus)

- Weeping beech (Fagus sylvatica tortuosa)

- Buttonwood (Platanus)

The rarer species include:

- Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba)

- Silk tree (Albizia julibrissin)

- Honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos)

- Princess tree (Paulownia tomentosa)

- Pride of India (Koelreuteria bipinnata)

The most common shrubs are:

- Spindle (Euonymus)

- Mahonia (Mahonia)

- Boxwood (Buxus)

- Aucuba (Aucuba)

- Viburnum rhytidophyllum (Viburnum)

- Tinus (Laurustinus Viburnum)

The lake in Parc Montsouris is home to swans, ducks and a wide variety of other waterfowl.

The lake in Parc Montsouris is home to swans, ducks and a wide variety of other waterfowl. Weeping beeches (Fagus sylvatica tortuosa) encircle the central lake of Parc Montsouris.

Weeping beeches (Fagus sylvatica tortuosa) encircle the central lake of Parc Montsouris. An Emperor Goose (Anser canagicus) lying on a bed of magnolia leaves close to the lake in Parc Montsouris.

An Emperor Goose (Anser canagicus) lying on a bed of magnolia leaves close to the lake in Parc Montsouris. Two painted buckeye (aesculus sylvatica) trees on the upper lawn near at the entrance of Parc Montsouris. They are exceptionally large because they have been grafted onto horse-chestnut trees (aesculus hippocastanum).

Two painted buckeye (aesculus sylvatica) trees on the upper lawn near at the entrance of Parc Montsouris. They are exceptionally large because they have been grafted onto horse-chestnut trees (aesculus hippocastanum). A red Dawn Redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides), the single one in Parc Montsouris, is framed by a Paper Birch (Betula papyrifera) to its left and an Austrian Pine (Pinus nigra) to its right.

A red Dawn Redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides), the single one in Parc Montsouris, is framed by a Paper Birch (Betula papyrifera) to its left and an Austrian Pine (Pinus nigra) to its right.

Art and architecture in the park

Sculptures in bronze and marble include:

- "Column of Armed Peace" by Jules-Felix Coutan (1889). This column was originally located in the Square d'Anvers. It replaced an 1889 allegorical statue of the French Revolution by Auguste Paris, which was removed and melted down for its metal in 1942 during the German occupation of Paris.[14] Coutan is known in the United States for his frieze on the facade of Grand Central Station in New York City.

- "First thrill" by René Baucour (1921)

- "Lion's death" by Edmond Desca (1929)

- "Women bathers" by Maurice Lipsi (1952)

- "Shipwrecked" by Antoine Étex (1859)

- "Desert drama" by Georges Gardet (1891)

- "Purity" by Costas Valsamis (1955)

- "Mine accident" by Henri Bouchard (1900)

- "Monument commemorating Colonel Flatters." This monument commemorates a French expedition of ninety-three men, led by the explorer and military officer Paul Flatters, which was massacred in 1881 by Tuareg tribesmen in the Sahara Desert of Algeria.

- "Statue of General José de San Martin," a monument to the leader of the fight for independence of the states of southern South America. This statue, put in place in 1960, is a replica of the original located in Santiago, Chile, made by Louis-Joseph Daumas.

- "Thomas Paine" sculpted by Gutzon Borglum in 1936, dedicated in 1948.

Shipwrecked, by Antoine Étex (1859).

Shipwrecked, by Antoine Étex (1859). A monument to the expedition of Colonel Paul Flatters, a French soldier and explorer, which was massacred by Tuareg tribesmen while crossing the Sahara desert in Algeria in 1881.

A monument to the expedition of Colonel Paul Flatters, a French soldier and explorer, which was massacred by Tuareg tribesmen while crossing the Sahara desert in Algeria in 1881. "Column of the Armed Peace" by Jules-Felix Coutan (1887). This work originally stood in the Square d'Anvers. It replaced a bronze statue symbolizing the French Revolution melted down by the Germans in 1942.

"Column of the Armed Peace" by Jules-Felix Coutan (1887). This work originally stood in the Square d'Anvers. It replaced a bronze statue symbolizing the French Revolution melted down by the Germans in 1942. Desert drama by Georges Gardet. (1891)

Desert drama by Georges Gardet. (1891) Lion's death by Edmond Desca (1929).

Lion's death by Edmond Desca (1929). Statue of José de San Martin (1778–1850), liberator of southern South America, a replica of a work by Louis-Joseph Daumas.

Statue of José de San Martin (1778–1850), liberator of southern South America, a replica of a work by Louis-Joseph Daumas.

References

Notes and citations

- Patrice de Moncan, Les Jardins du Baron Haussmann, pg. 191.

- Paris portal: Principaux parcs: Parc Montsouris (in French)

- Rene-Leon Cottard (1988), Vie et histoire du XIV Arrondissement - Montsouris, Petit Montrouge, Plaisance: histoire, anecdotes, curiosities, monuments. Hervas.

- Le parc Montsouris Archived 2013-05-09 at the Wayback Machine Link to Parc Montsouris on the official site of the City of Paris

- Auguste Longnon (1920), Les noms de lieu de la France, leur origin, leur signification, leur transformations. p. 546.

- Paris, the Early Roman City: The Saint-Jacques Necropolis

- Les Légendes Epiques, Bedier, Joseph - excerpt from Gervase of Tilbury's Otia Imperialia (~1212)

- Emile, Gerards (1908). Paris Souterrain. Paris, France. p. 443. ISBN 2-84022-002-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hillairet, Jacques (1956). Connaissance du Vieux Paris. Vol. v.3. Paris, France. p. 15. ISBN 2-85961-019-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - A. Alphand, Les Promenades de Paris

- Patrice de Moncan, Les Jardins du Baron Haussmann, pp. 97–98.

- Dominique Jarrassé, Grammaire des jardins Parisiens, p. 132

- Dominique Jarrassé, Grammaire des jardins Parisiens, p. 130

- Dominique Jarrassé, Grammaire des jardins Parisiens, p. 130.

Bibliography

- Downie, David (2005), Paris, Paris: Journey into the City of Light, Fort Bragg: Transatlantic Press, ISBN 0-9769251-0-9: "Montsouris and Buttes-Chaumont: the art of the faux", pp. 34–41

- Patrice de Moncan (2009). Paris - Les jardins du Baron Haussmann, Les Éditions du Mécène, ISBN 978-2-907970-914

- Dominique Jarrassé (2007), Grammaire des Jardins Parisiens, Parigramme, Paris, ISBN 978-2-84096-476-6.

External links

- Le parc Montsouris Link to Parc Montsouris on the official site of the City of Paris

- Parc Montsouris — Postcards of the park from the beginning of the 20th century.

- Trees and shrubs (in English)