Mordialloc Aboriginal Reserve

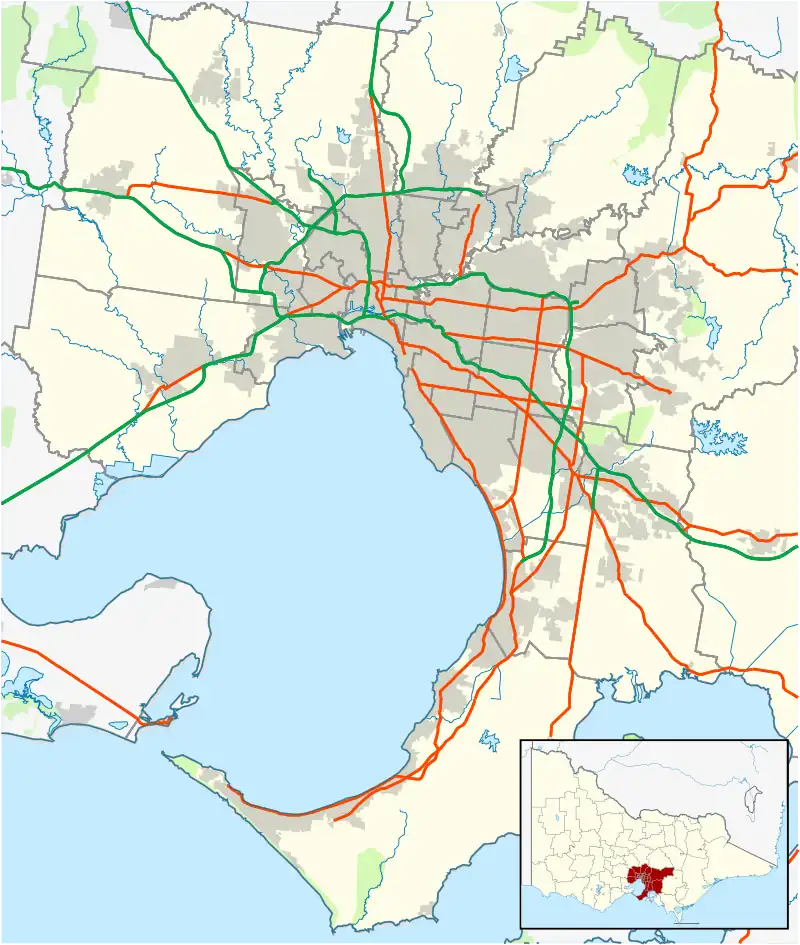

Mordialloc Aboriginal Reserve in Victoria on the coast of Port Phillip Bay was on traditional land of the Bunurong people to which they gradually retreated from surrounding areas after white settlement from the 1850s. Most had moved, or had been relocated, to Coranderk by the mid-1860s.

| Mordialloc Aboriginal Reserve Mordy Yallock Melbourne, Victoria | |

|---|---|

Mordialloc Aboriginal Reserve | |

| Coordinates | 37°59′58″S 145°05′46″E |

| Population | 26 (Aboriginal people in 1869)[1] |

| • Density | 7.72/km2 (20.0/sq mi) |

| Established | 1852 |

| Postcode(s) | 3195 |

| Area | 3.37 km2 (1.3 sq mi) |

| Guardian of the Aborigines | William Thomas |

| LGA(s) | City of Kingston |

Traditional lands

The Boon Wurrung (or Bunurong) peoples of the Kulin nation lived along the Eastern coast of Port Philip Bay for over 20,000 years before white settlement.[2] Their mythology preserves the history of the flooding of Port Phillip Bay 10,000 years ago,[3] and its period of drying and retreat 2,800–1,000 years ago (see: Prehistory of Australia).[4] Visible evidence of their shell middens and hand-dug wells remain along the cliffs of Beaumaris,[5][6] and as scar trees from which bark was taken for canoes along Mordialloc Creek.[7]

The Bunurong first encountered white Europeans when in February 1801 Lady Nelson sailed into Port Phillip and they met crewmen who had landed at what is now Sorrento where in 1803 David Collins disembarked with 467 convicts, leaving after eight months after finding the site "unpromising and unproductive".[8]

By the 1850s most Bunurong withdrew to the Mordialloc Aboriginal Reserve established in 1852 which encompassed 337 hectares (832 acres) alongside the Mordialloc Creek and Port Phillip Bay. Mordy yallock (yallock meaning 'creek' in Boonwurrung language)[9] was a favourite traditional camping ground with wild fowl in the fens of Carrum Swamp, and where fish came to spawn in the creek,[10] though netting upstream by settlers, officially banned but not enforced, later limited their catch.[11]

Protectorate

William Thomas[12][13] had been appointed Guardian of the Yarra and Western Port tribes of in 1850, having been Assistant Protector since 1837,[14][15] and since 1853 was to have regularly supplied them blankets and food, a task he delegated in Mordialloc to a local squatter Mr A. V. Macdonald.[16][17][18][19] Thomas assured the Select Committee of the health of the Boonwurrung people and of their fondness for the Mordialloc Aboriginal Reserve, saying: "...as far as the necessities of life are concerned... They want for nothing."[20]

The area was not, however, for their exclusive use; in the Victorian Legislative Council sitting of October 1858 correspondence was tabled complaining that fishermen at Mordialloc were being charged "about £6 per annum...for tenting on the sands at Mordialloc...in a reserve of land from the Crown for the aborigines..."[21] and in 1861 the reserve was incorporated in the Farmers' Common of 3,220 hectares (7,960 acres).[22]

After widespread reporting that year[23] of the coroner's inquest into the death of indigenous woman Betsy and her newborn infant due to exposure and malnourishment aroused some outrage,[24][21] George Harris Warren was appointed[25] in March 1862 to be 'honorary correspondent' at Mordialloc, reporting on the distribution of food and supplies, to the Central Board for Watching over the Interests of the Aborigines that had been established in 1860.[1]

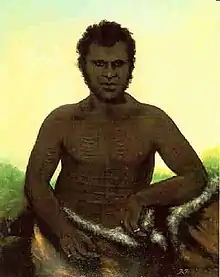

The number of Aboriginal Australians in reserves in Victoria was estimated by the Board on 31 May 1869 to be 1,834, of which 26 were in Mordialloc.[1] In a dream of his totem the koala, song man Kubaru of the Bunerong Mordialloc tribe envisaged a great disaster to his people, "All gone dead." Nancy and Jimmy Dunbar died in 1877, the last Bunurong people from the Mordialloc camp.[26]

In 1878 the Minister of Lands, in deciding on the application by George Langridge for 4.0 hectares (10 acres) at Mordialloc "believed to have been reserved for an aboriginal reserve", denied that the Lands department had ever allocated it to such purpose.[27]

References

- "The Aborigines". The Argus. 10 August 1869. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- Tindale, Norman B. (1974). "Bunurong (VIC)". Aboriginal tribes of Australia: their terrain, environmental controls, distribution, limits, and proper names. Canberra: Australian National University Press. ISBN 0-7081-0741-9. OCLC 3052288.

- "Boon Wurrung: The Filling of the Bay – The Time of Chaos – Nyernila". Culture Victoria. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- Holdgate, G. R.; Wagstaff, B.; Gallagher, S. J. (2011). "Did Port Phillip Bay nearly dry up between ~2800 and 1000 cal. yr BP? Bay floor channelling evidence, seismic and core dating". Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. Informa UK Limited. 58 (2): 157–175. Bibcode:2011AuJES..58..157H. doi:10.1080/08120099.2011.546429. ISSN 0812-0099. S2CID 128710768.

- Massola, Aldo (1959). The native water wells of Beaumaris and Black Rock. OCLC 815509348.

- Brooks, A. E. (1960), The Aboriginal Well at Beaumaris

- Eidelson, Meyer (2014). Melbourne dreaming: a guide to important places of the past and the present. Aboriginal Studies Press. ISBN 978-1-922059-71-0. OCLC 889665763.

- Broome, Richard (2006). Aboriginal Victorians: a history since 1800. Crows Nest NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74114-569-4. OCLC 68773150.

- Massola, Aldo (1968). Aboriginal place names of south-east Australia and their meanings. Melbourne: Lansdowne. OCLC 40364.

- "Page 9". Truth. 23 November 1913. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- "News Of The Week". Leader. 20 February 1864. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- Mulvaney, D. J. "William Thomas (1793–1867)". Thomas, William (1793–1867). Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- Stephens, Marguerita (2014). The journal of William Thomas: assistant protector of the Aborigines of Port Phillip & guardian of the Aborigines of Victoria 1839 to 1843. Melbourne, Victoria. ISBN 978-0-9871337-7-9. OCLC 886362023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Reed, Liz (January 2011). "Rethinking William Thomas, 'friend' of the Aborigines". Aboriginal History. 28. doi:10.22459/ah.28.2011.04. ISSN 0314-8769.

- Thomas, William (2005). A cloud of hapless foreboding : Assistant Protector William Thomas and the Port Phillip aborigines, 1839-1840. Richard Cotter, Nepean Historical Society. Sorrento, Vic.: Nepean Historical Society. ISBN 0-9757127-5-6. OCLC 69676369.

- "The Gazette". The Argus. 22 March 1862. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- "Quis Custodiet Ipsos Custodes". Melbourne Punch. 10 October 1861. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- Macdonald, A. V. (4 October 1861). "The Mordialloc Aboriginal Inquest: To the Editor of the Argus". The Argus. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- "The Aborigines In Victoria". The Argus. 21 August 1868. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- Clark, Ian D (1 December 2005). "'You have all this place, no good have children ...' Derrimut: traitor, saviour, or a man of his people?". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. Royal Australian Historical Society. 91 (2): 107–132. ISSN 0035-8762.

- "The News of the Day". The Age. 13 October 1858. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- "Farmers' Commons". The Age. 27 February 1861. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- For example:

- "The News of the Day". The Age. 25 September 1861. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- "Death of an Aboriginal Woman and Her Infant". The Argus. 25 September 1861. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- "Town Talk". The Herald. 25 September 1861. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- "Wednesday, September 25, 1861". The Argus. 25 September 1861. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- "Melbourne News". Bendigo Advertiser. 27 September 1861. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- "News of the Week". Melbourne Leader. 28 September 1861. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- "The Mordialloc Inquest Upon the Aboriginal Betsy and Her Child - To the Editor of The Argus". The Argus. 28 September 1861. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- "Government Gazette". The Age. 22 March 1862. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- Close, D.K. (2021). Sounding 3: Black Lives and White Lies. Buckley, Batman & Myndie: Echoes of the Victorian culture-clash frontier. BookPOD. ISBN 978-0-9922904-1-2.

- "Thursday June 6, 1878". The Argus. 6 June 1878. Retrieved 29 November 2021.