Melancholia

Melancholia or melancholy (from Greek: µέλαινα χολή melaina chole,[1] meaning black bile)[2] is a concept found throughout ancient, medieval, and premodern medicine in Europe that describes a condition characterized by markedly depressed mood, bodily complaints, and sometimes hallucinations and delusions.

Melancholy was regarded as one of the four temperaments matching the four humours.[3] Until the 18th century, doctors and other scholars classified melancholic conditions as such by their perceived common cause – an excess of a notional fluid known as "black bile", which was commonly linked to the spleen. Hippocrates and other ancient physicians described melancholia as a distinct disease with mental and physical symptoms, including persistent fears and despondencies, poor appetite, abulia, sleeplessness, irritability, and agitation.[4][5] Later, fixed delusions were added by Galen and other phycisians to the list of symptoms.[6][7] In the Middle Ages, the understanding of melancholia shifted to a religious perspective,[8][9] with sadness seen as a vice and demonic possession, rather than somatic causes, as a potential cause of the disease.[10]

During the late 16th and early 17th centuries, a cultural and literary cult of melancholia emerged in England, linked to Neoplatonist and humanist Marsilio Ficino's transformation of melancholia from a sign of vice into a mark of genius. This fashionable melancholy became a prominent theme in literature, art, and music of the era.

Between the late 18th and late 19th centuries, melancholia was a common medical diagnosis.[11] In this period, the focus was on the abnormal beliefs associated with the disorder, rather than depression and affective symptoms.[7] However, in the 20th century, the focus again shifted, and the term became used essentially as a synonym for depression.[7] Indeed, modern concepts of depression as a mood disorder eventually arose from this historical context.[12] Today, the term "melancholia" and "melancholic" are still used in medical diagnostic classification, such as in ICD-11 and DSM-5, to specify certain features that may be present in major depression.[13][14]

Related terms used in historical medicine include lugubriousness (from Latin lugere: "to mourn"),[15][16] moroseness (from Latin morosus: "self-will or fastidious habit"),[16][17] wistfulness (from a blend of "wishful" and the obsolete English wistly, meaning "intently"),[16][18] and saturnineness (from Latin Saturninus: "of the planet Saturn).[19][20]

Early history

.jpg.webp)

The name "melancholia" comes from the old medical belief of the four humours: disease or ailment being caused by an imbalance in one or more of the four basic bodily liquids, or humours. Personality types were similarly determined by the dominant humor in a particular person. According to Hippocrates and subsequent tradition, melancholia was caused by an excess of black bile,[21] hence the name, which means "black bile", from Ancient Greek μέλας (melas), "dark, black",[22] and χολή (kholé), "bile";[23] a person whose constitution tended to have a preponderance of black bile had a melancholic disposition. In the complex elaboration of humorist theory, it was associated with the earth from the Four Elements, the season of autumn, the spleen as the originating organ and cold and dry as related qualities. In astrology it showed the influence of Saturn, hence the related adjective saturnine.[19][20]

Melancholia was described as a distinct disease with particular mental and physical symptoms in the 5th and 4th centuries BC. Hippocrates, in his Aphorisms, characterized all "fears and despondencies, if they last a long time" as being symptomatic of melancholia.[4] Other symptoms mentioned by Hippocrates include: poor appetite, abulia, sleeplessness, irritability, agitation.[5] The Hippocratic clinical description of melancholia shows significant overlaps with contemporary nosography of depressive syndromes (6 symptoms out of the 9 included in DSM [24] diagnostic criteria for a Major Depressive).[25]

In ancient Rome, Galen added "fixed delusions" to the set of symptoms listed by Hippocrates. Galen also believed that melancholia caused cancer.[6] Aretaeus of Cappadocia, in turn, believed that melancholia involved both a state of anguish, and a delusion.[7] In the 10th century Persian physician Al-Akhawayni Bokhari described melancholia as a chronic illness caused by the impact of black bile on the brain.[26] He described melancholia's initial clinical manifestations as "suffering from an unexplained fear, inability to answer questions or providing false answers, self-laughing and self-crying and speaking meaninglessly, yet with no fever."[27]

In Middle-Ages Europe, the humoral, somatic paradigm for understanding sustained sadness lost primacy in front of the prevailing religious perspective.[8][9] Sadness came to be a vice (λύπη in the Greek vice list by Evagrius Ponticus,[28] tristitia vel acidia in the 7 vice list by Pope Gregory I).[29] When a patient could not be cured of the disease it was thought that the melancholia was a result of demonic possession.[10][30]

In his study of French and Burgundian courtly culture, Johan Huizinga[31] noted that "at the close of the Middle Ages, a sombre melancholy weighs on people's souls." In chronicles, poems, sermons, even in legal documents, an immense sadness, a note of despair and a fashionable sense of suffering and deliquescence at the approaching end of times, suffuses court poets and chroniclers alike: Huizinga quotes instances in the ballads of Eustache Deschamps, "monotonous and gloomy variations of the same dismal theme", and in Georges Chastellain's prologue to his Burgundian chronicle,[32] and in the late 15th-century poetry of Jean Meschinot. Ideas of reflection and the workings of imagination are blended in the term merencolie, embodying for contemporaries "a tendency", observes Huizinga, "to identify all serious occupation of the mind with sadness".[33]

Painters were considered by Vasari and other writers to be especially prone to melancholy by the nature of their work, sometimes with good effects for their art in increased sensitivity and use of fantasy. Among those of his contemporaries so characterised by Vasari were Pontormo and Parmigianino, but he does not use the term of Michelangelo, who used it, perhaps not very seriously, of himself.[34] A famous allegorical engraving by Albrecht Dürer is entitled Melencolia I. This engraving has been interpreted as portraying melancholia as the state of waiting for inspiration to strike, and not necessarily as a depressive affliction. Amongst other allegorical symbols, the picture includes a magic square and a truncated rhombohedron.[35] The image in turn inspired a passage in The City of Dreadful Night by James Thomson (B.V.), and, a few years later, a sonnet by Edward Dowden.

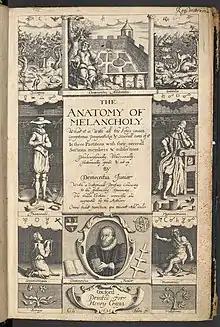

The most extended treatment of melancholia comes from Robert Burton, whose The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) treats the subject from both a literary and a medical perspective. His concept of melancholia includes all mental illness, which he divides into different types. Burton wrote in the 17th century that music and dance were critical in treating mental illness.[36]

But to leave all declamatory speeches in praise of divine music, I will confine myself to my proper subject: besides that excellent power it hath to expel many other diseases, it is a sovereign remedy against despair and melancholy, and will drive away the devil himself. Canus, a Rhodian fiddler, in Philostratus, when Apollonius was inquisitive to know what he could do with his pipe, told him, "That he would make a melancholy man merry, and him that was merry much merrier than before, a lover more enamoured, a religious man more devout." Ismenias the Theban, Chiron the centaur, is said to have cured this and many other diseases by music alone: as now they do those, saith Bodine, that are troubled with St. Vitus's Bedlam dance.[37][38][39]

In the Encyclopédie of Diderot and d'Alembert, the causes of melancholia are stated to be similar to those that cause Mania: "grief, pains of the spirit, passions, as well as all the love and sexual appetites that go unsatisfied."[40]

English cultural movement

.jpg.webp)

During the later 16th and early 17th centuries, a curious cultural and literary cult of melancholia arose in England. In an influential[41][42] 1964 essay in Apollo, art historian Roy Strong traced the origins of this fashionable melancholy to the thought of the popular Neoplatonist and humanist Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499), who replaced the medieval notion of melancholia with something new:

Ficino transformed what had hitherto been regarded as the most calamitous of all the humours into the mark of genius. Small wonder that eventually the attitudes of melancholy soon became an indispensable adjunct to all those with artistic or intellectual pretentions.[43]

The Anatomy of Melancholy (The Anatomy of Melancholy, What it is: With all the Kinds, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of it... Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically, Opened and Cut Up) by Burton, was first published in 1621 and remains a defining literary monument to the fashion. Another major English author who made extensive expression upon being of an melancholic disposition is Sir Thomas Browne in his Religio Medici (1643).

Night-Thoughts (The Complaint: or, Night-Thoughts on Life, Death, & Immortality), a long poem in blank verse by Edward Young was published in nine parts (or "nights") between 1742 and 1745, and hugely popular in several languages. It had a considerable influence on early Romantics in England, France and Germany. William Blake was commissioned to illustrate a later edition.

In the visual arts, this fashionable intellectual melancholy occurs frequently in portraiture of the era, with sitters posed in the form of "the lover, with his crossed arms and floppy hat over his eyes, and the scholar, sitting with his head resting on his hand"[43] – descriptions drawn from the frontispiece to the 1638 edition of Burton's Anatomy, which shows just such by-then stock characters. These portraits were often set out of doors where Nature provides "the most suitable background for spiritual contemplation"[44] or in a gloomy interior.

In music, the post-Elizabethan cult of melancholia is associated with John Dowland, whose motto was Semper Dowland, semper dolens ("Always Dowland, always mourning"). The melancholy man, known to contemporaries as a "malcontent", is epitomized by Shakespeare's Prince Hamlet, the "Melancholy Dane".

A similar phenomenon, though not under the same name, occurred during the German Sturm und Drang movement, with such works as The Sorrows of Young Werther by Goethe or in Romanticism with works such as Ode on Melancholy by John Keats or in Symbolism with works such as Isle of the Dead by Arnold Böcklin. In the 20th century, much of the counterculture of modernism was fueled by comparable alienation and a sense of purposelessness called "anomie"; earlier artistic preoccupation with death has gone under the rubric of memento mori. The medieval condition of acedia (acedie in English) and the Romantic Weltschmerz were similar concepts, most likely to affect the intellectual.[45]

Modern connotations

In the 18th to 19th centuries, the concept of "melancholia" became almost solely about abnormal beliefs, and lost its attachment to depression and other affective symptoms.[7]

Melancholia was a category that "the well-to-do, the sedentary, and the studious were even more liable to be placed in the eighteenth century than they had been in preceding centuries."[46][47]

In the 20th century, "melancholia" lost its attachment to abnormal beliefs, and in common usage became entirely a synonym for depression.[7] Sigmund Freud published a paper on Mourning and Melancholia in 1918. In the early 20th century, some believed there was distinct condition called involutional melancholia, a low mood disorder affecting people of advanced age.

In 1996, Gordon Parker and Dusan Hadzi-Pavlovic described "melancholia" as a specific disorder of movement and mood.[48] They attached the term to the concept of "endogenous depression" (claimed to be caused by internal forces rather than environmental influences).[49]

In 2006, Michael Alan Taylor and Max Fink also defined melancholia as a systemic disorder that could be identified by depressive mood rating scales, verified by the presence of abnormal cortisol metabolism.[50] They considered it to be characterized by depressed mood, abnormal motor functions, and abnormal vegetative signs, and they described several forms, including retarded depression, psychotic depression and postpartum depression.[50]

For the purposes of medical diagnostic classification, the terms "melancholia" and "melancholic" are still in use (for example, in ICD-11 and DSM-5) to specify certain features that may be present in major depression, such as:[13][14]

- severely depressed mood, wherein the person often feels despondent, forlorn, disconsolate, or empty

- pervasive anhedonia – loss of interest or pleasure in most activities that are normally enjoyable

- lack of emotional responsiveness (mood does not brighten, even briefly) to normally pleasurable stimuli (such as food or entertainment) or situations (such as warm, affectionate interactions with friends or family)

- terminal insomnia – unwanted early morning awakening (two or more hours earlier than normal)

- marked psychomotor retardation or agitation

- marked loss of appetite or weight loss

In May 2020, BBC Radio 4 broadcast a twelve part series titled The New Anatomy of Melancholy, looking at depression from the perspectives of Robert Burton's 1621 book The Anatomy of Melancholy.[51]

See also

Citations

- Burton, Bk. I, p. 147

- Bell M (2014). Melancholia: The Western Malady. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-107-06996-1. Archived from the original on 2022-08-28. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- "The Four Human Temperaments". www.thetransformedsoul.com. Archived from the original on 2022-07-07. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- Hippocrates, Aphorisms, Section 6.23

- Epidemics, III, 16 cases, case II

- Clarke, R. J.; Macrae, R. (1988). Coffee: Physiology. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-85166-186-2. Archived from the original on 2022-07-03. Retrieved 2022-08-28 – via Google Books.

- Telles-Correia, Diogo; Marques, João Gama (3 February 2015). "Melancholia Before the Twentieth Century: Fear and Sorrow or Partial Insanity?". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 81. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00081. PMC 4314947. PMID 25691879.

- Azzone P. (2013) pp. 23ff.

- Azzone P (2012) Sin of Sadness: Acedia vel Tristitia Between Sociocultural Conditioning and Psychological Dynamics of Negative Emotions. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 31: 50–64.

- "18th-Century Theories of Melancholy & Hypochondria". loki.stockton.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- Berrios G E (1988) Melancholia and Depression during the 19th Century. British Journal of Psychiatry 153: 289–304

- Kendler KS (August 2020). "The Origin of Our Modern Concept of Depression-The History of Melancholia from 1780–1880: A Review" (PDF). JAMA Psychiatry. 77 (8): 863–868. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4709. PMID 31995137. S2CID 210949394. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-08-12. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- World Health Organization, "6A80.3 Current depressive episode with melancholia", International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th rev. (September 2020).

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). United States: American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-89042-557-2. Archived from the original on 2021-07-10. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- "Definition of Lugubrious". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- Porter, Stanley C.; Malcolm, Matthew R., eds. (2013-04-25). Horizons in Hermeneutics: A Festschrift in Honor of Anthony C. Thiselton. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-8028-6927-2.

Melancholia [is] also translated as "lugubriousness," "moroseness," or "wistfulness".

- "Definition of Moroseness". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- "Definition of Wistfulness". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- "Definition of Saturnine". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- Wallace, Ian, ed. (2015). Voices from Exile: Essays in Memory of Hamish Ritchie. Brill. p. 213. ISBN 978-90-04-29639-8.

[This is] what humour-based physiology of the renaissance and baroque periods described as saturnine melancholia.

- Hippocrates, De aere aquis et locis, 10.103 Archived 2022-06-01 at the Wayback Machine, on Perseus Digital Library

- μέλας Archived 2011-06-05 at the Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- χολή Archived 2022-07-08 at the Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Fifth Edition. APA, Washington DC., pp. 160–161.

- Azzone P. (2013): Depression as a Psychoanalytic Problem. University Press of America, Lanham, Md., 2013

- Delfaridi, Behnam (2014). "Melancholia in Medieval Persian Literature: The View of Hidayat of Al-Akhawayni". World Journal of Psychiatry. 4 (2): 37–41. doi:10.5498/wjp.v4.i2.37. PMC 4087154. PMID 25019055.

- Matini, Jalal (1965). Hedayat al-Motaallemin fi Tebb. University Press, Mashhad.

- Guillamont A., Guillamont C. (Eds.) (1971) Évagre le Pontique. Traité pratique ou le moine, 2 VV.. Sources Chrétiennes 170–171, Les Éditions du Cerf, Paris

- Gregorius Magnus. Moralia in Iob. In J.-P. Migne (Ed.) Patrologiae Latinae cursus completus (Vol. 75, col. 509D – Vol. 76, col. 782AG)

- Farmer, Hugh. An essay on demoniacs of the New Testament 56 (1818)

- Huizinga, "Pessimism and the ideal of the sublime life", The Waning of the Middle Ages, 1924:22ff.

- "I, man of sadness, born in an eclipse of darkness, and thick fogs of lamentation".

- Huizinga 1924:25.

- Britton, Piers, "Mio malinchonico, o vero... mio pazzo": Michelangelo, Vasari, and the Problem of Artists' Melancholy in Sixteenth-Century Italy, The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 34, No. 3 (Fall, 2003), pp. 653–675, doi:10.2307/20061528, JSTOR Archived 2020-11-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Dürer's Solid". mathworld.wolfram.com. Archived from the original on 2022-01-30. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- Cf. The Anatomy of Melancholy, subsection 3, on and after line 3480, "Music a Remedy":

- "Gutenberg.org". Archived from the original on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- "Humanities are the Hormones: A Tarantella Comes to Newfoundland. What should we do about it?" Archived February 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine by Dr. John Crellin, Munmed, newsletter of the Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1996.

- Aung, Steven K.H.; Lee, Mathew H.M. (2004). "Music, Sounds, Medicine, and Meditation: An Integrative Approach to the Healing Arts". Alternative & Complementary Therapies. 10 (5): 266–270. doi:10.1089/act.2004.10.266.

- Denis Diderot (2015). "Melancholia". The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- Goldring, Elizabeth (August 2005). "'So Lively a Portrait of His Miseries': Melancholy, Mourning, and the Elizabethan malady". British Art Journal. 6 (2): 12–22. JSTOR 41614620. – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Ribeiro, Aileen (2005). Fashion and Fiction: Dress in Art and Literature in Stuart England. New Haven CN; London: Yale University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-300-10999-3.

- Strong, Roy (1964). "The Elizabethan Malady: Melancholy in Elizabeth and Jacobean Portraiture". Apollo. LXXIX., reprinted in Strong, Roy (1969). The English Icon: Elizabethan and Jacobean Portraiture. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Ribeiro, Aileen (2005). Fashion and Fiction: Dress in Art and Literature in Stuart England. New Haven, CN; London: Yale University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-300-10999-3.

- Perpinyà, Núria (2014). Ruins, Nostalgia and Ugliness. Five Romantic Perceptions of Middle Ages and a Spoon of Game of Thrones and Avant-Garde Oddity Archived 2016-03-13 at the Wayback Machine. Berlin: Logos Verlag

- Wear, A (2001). The Oxford Companion to the Body. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2021-10-15. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- Ordronaux, John (1871). Regimen sanitatis salernitanum. Code of health of the school of Salernum. Philadelphia, J.B. Lippincott & co.

- Parker, Gordon; Hadzi-Pavlovic, Dusan, eds. (1996). Melancholia: A Disorder of Movement and Mood: A Phenomenological and Neurobiological Review. Sydney: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511759024. ISBN 978-0-521-47275-3. Archived from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- Parker, Gordon. "Back to Black: Why Melancholia Must Be Understood as Distinct from Depression". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2022-03-30. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- Taylor, Michael Alan; Fink, Max (2006). Melancholia: The Diagnosis, Pathophysiology and Treatment of Depressive Illness. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84151-1. Archived from the original on 2022-05-03. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- "New BBC Radio Series: The Anatomy of Melancholy – Department of Psychiatry". www.psych.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2022-05-11. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

Further reading

- Azzone, Paolo: Depression as a Psychoanalytic Problem. University Press of America, Lanham, Md., 2013. ISBN 978-0-761-86041-9

- Blazer, Dan G.: The Age of Melancholy: "Major Depression" and its Social Origin. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 978-0-415-95188-3

- Bowring, Jacky: A Field Guide to Melancholy. Oldcastle Books, 2009. ISBN 978-1-842-43292-1

- Boym, Svetlana: The Future of Nostalgia. Basic Books, 2002. ISBN 978-0-465-00708-0

- Jackson, Stanley W.: Melancholia and Depression: From Hippocratic Times to Modern Times. Yale University Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0-300-03700-5

- Klibansky, Raymond; Panofsky, Erwin; Saxl, Fritz: Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion, and Art. McGill-Queen's Press, 1964 [2019] ISBN 978-0-7735-5952-3

- Kristeva, Julia: Black Sun. Columbia University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0-231-06707-2

- Radden, Jennifer: The Nature of Melancholy: From Aristotle to Kristeva. Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-195-15165-7

- Schwenger, Peter: The Tears of Things: Melancholy and Physical Objects. University of Minnesota Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-816-64631-9

- Shenk, Joshua W.: Lincoln's Melancholy: How Depression Challenged a President and Fueled His Greatness. Mariner Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0-618-77344-2

- Various: Melancholy Experience in Literature of the Long Eighteenth Century. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. ISBN 978-1-349-31949-7

External links

- Grunwald Center website: Durer's Melencolia and clinical depression, iconography and printmaking techniques

- "Dürer's Melancholia": sonnet by Edward Dowden

- Melancholy and abstraction, on the Berlin exhibition "Melancholy: Genius and Madness in Art"

- Diderot's historic writing on Melancholy

- "The Four Humours" on "In Our Time"

- "An Anatomy of Melancholy" on "In Our Time"

- At the Roots of Melancholy