Moscow Mathematical Papyrus

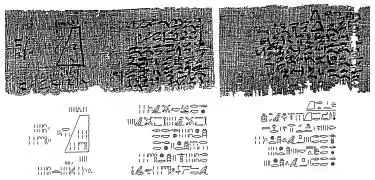

The Moscow Mathematical Papyrus, also named the Golenishchev Mathematical Papyrus after its first non-Egyptian owner, Egyptologist Vladimir Golenishchev, is an ancient Egyptian mathematical papyrus containing several problems in arithmetic, geometry, and algebra. Golenishchev bought the papyrus in 1892 or 1893 in Thebes. It later entered the collection of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow, where it remains today.

| Moscow Mathematical Papyrus | |

|---|---|

| Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow | |

14th problem of the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus (V. Struve, 1930) | |

| Date | 13th dynasty, Second Intermediate Period of Egypt |

| Place of origin | Thebes |

| Language(s) | Hieratic |

| Size | Length: 5.5 metres (18 ft) Width: 3.8 to 7.6 cm (1.5 to 3 in) |

Based on the palaeography and orthography of the hieratic text, the text was most likely written down in the 13th Dynasty and based on older material probably dating to the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt, roughly 1850 BC.[1] Approximately 5½ m (18 ft) long and varying between 3.8 and 7.6 cm (1.5 and 3 in) wide, its format was divided by the Soviet Orientalist Vasily Vasilievich Struve[2] in 1930[3] into 25 problems with solutions.

It is a well-known mathematical papyrus, usually referenced together with the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus. The Moscow Mathematical Papyrus is older than the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, while the latter is the larger of the two.[4]

Exercises contained in the Moscow Papyrus

The problems in the Moscow Papyrus follow no particular order, and the solutions of the problems provide much less detail than those in the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus. The papyrus is well known for some of its geometry problems. Problems 10 and 14 compute a surface area and the volume of a frustum respectively. The remaining problems are more common in nature.[1]

Ship's part problems

Problems 2 and 3 are ship's part problems. One of the problems calculates the length of a ship's rudder and the other computes the length of a ship's mast given that it is 1/3 + 1/5 of the length of a cedar log originally 30 cubits long.[1]

Aha problems

| ꜥḥꜥ (aha) in hieroglyphs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Era: New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC) | |||

Aha problems involve finding unknown quantities (referred to as aha, "stack") if the sum of the quantity and part(s) of it are given. The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus also contains four of these type of problems. Problems 1, 19, and 25 of the Moscow Papyrus are Aha problems. For instance, problem 19 asks one to calculate a quantity taken 1 and ½ times and added to 4 to make 10.[1] In other words, in modern mathematical notation one is asked to solve .

Pefsu problems

Most of the problems are pefsu problems (see: Egyptian algebra): 10 of the 25 problems. A pefsu measures the strength of the beer made from a hekat of grain

A higher pefsu number means weaker bread or beer. The pefsu number is mentioned in many offering lists. For example, problem 8 translates as:

- (1) Example of calculating 100 loaves of bread of pefsu 20

- (2) If someone says to you: "You have 100 loaves of bread of pefsu 20

- (3) to be exchanged for beer of pefsu 4

- (4) like 1/2 1/4 malt-date beer"

- (5) First calculate the grain required for the 100 loaves of the bread of pefsu 20

- (6) The result is 5 heqat. Then reckon what you need for a des-jug of beer like the beer called 1/2 1/4 malt-date beer

- (7) The result is 1/2 of the heqat measure needed for des-jug of beer made from Upper-Egyptian grain.

- (8) Calculate 1/2 of 5 heqat, the result will be 2 1/2

- (9) Take this 2 1/2 four times

- (10) The result is 10. Then you say to him:

- (11) "Behold! The beer quantity is found to be correct."[1]

Baku problems

Problems 11 and 23 are Baku problems. These calculate the output of workers. Problem 11 asks if someone brings in 100 logs measuring 5 by 5, then how many logs measuring 4 by 4 does this correspond to? Problem 23 finds the output of a shoemaker given that he has to cut and decorate sandals.[1]

Two geometry problems

Problem 10

The tenth problem of the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus asks for a calculation of the surface area of a hemisphere (Struve, Gillings) or possibly the area of a semi-cylinder (Peet). Below we assume that the problem refers to the area of a hemisphere.

The text of problem 10 runs like this: "Example of calculating a basket. You are given a basket with a mouth of 4 1/2. What is its surface? Take 1/9 of 9 (since) the basket is half an egg-shell. You get 1. Calculate the remainder which is 8. Calculate 1/9 of 8. You get 2/3 + 1/6 + 1/18. Find the remainder of this 8 after subtracting 2/3 + 1/6 + 1/18. You get 7 + 1/9. Multiply 7 + 1/9 by 4 + 1/2. You get 32. Behold this is its area. You have found it correctly."[1][5]

The solution amounts to computing the area as

The formula calculates for the area of a hemisphere, where the scribe of the Moscow Papyrus used to approximate π.

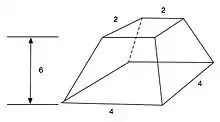

Problem 14: Volume of frustum of square pyramid

The fourteenth problem of the Moscow Mathematical calculates the volume of a frustum.

Problem 14 states that a pyramid has been truncated in such a way that the top area is a square of length 2 units, the bottom a square of length 4 units, and the height 6 units, as shown. The volume is found to be 56 cubic units, which is correct.[1]

The text of the example runs like this: "If you are told: a truncated pyramid of 6 for the vertical height by 4 on the base by 2 on the top: You are to square the 4; result 16. You are to double 4; result 8. You are to square this 2; result 4. You are to add the 16 and the 8 and the 4; result 28. You are to take 1/3 of 6; result 2. You are to take 28 twice; result 56. See, it is of 56. You will find [it] right" [6]

The solution to the problem indicates that the Egyptians knew the correct formula for obtaining the volume of a truncated pyramid:

where a and b are the base and top side lengths of the truncated pyramid and h is the height. Researchers have speculated how the Egyptians might have arrived at the formula for the volume of a frustum but the derivation of this formula is not given in the papyrus.[7]

Summary

Richard J. Gillings gave a cursory summary of the Papyrus' contents.[8] Numbers with overlines denote the unit fraction having that number as denominator, e.g. ; unit fractions were common objects of study in ancient Egyptian mathematics.

| No. | Detail |

|---|---|

| 1 | Damaged and unreadable. |

| 2 | Damaged and unreadable. |

| 3 | A cedar mast. of . Unclear. |

| 4 | Area of a triangle. of . |

| 5 | Pesus of loaves and bread. Same as No. 8. |

| 6 | Rectangle, area . Find and . |

| 7 | Triangle, area . Find and . |

| 8 | Pesus of loaves and bread. |

| 9 | Pesus of loaves and bread. |

| 10 | Area of curved surface of a hemisphere (or cylinder). |

| 11 | Loaves and basket. Unclear. |

| 12 | Pesu of beer. Unclear. |

| 13 | Pesus of loaves and beer. Same as No. 9. |

| 14 | Volume of a truncated pyramid. . |

| 15 | Pesu of beer. |

| 16 | Pesu of beer. Similar to No. 15. |

| 17 | Triangle, area . Find and . |

| 18 | Measuring cloth in cubits and palms. Unclear. |

| 19 | Solve the equation . Clear. |

| 20 | Pesu of 1000 loaves. Horus-eye fractions. |

| 21 | Mixing of sacrificial bread. |

| 22 | Pesus of loaves and beer. Exchange. |

| 23 | Computing the work of a cobbler. Unclear. Peet says very difficult. |

| 24 | Exchange of loaves and beer. |

| 25 | Solve the equation . Elementary and clear. |

Other papyri

Other mathematical texts from Ancient Egypt include:

- Berlin Papyrus 6619

- Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll

- Lahun Mathematical Papyri

- Rhind Mathematical Papyrus

General papyri:

- Papyrus Harris I

- Rollin Papyrus

For the 2/n tables see:

See also

Notes

- This table is a verbatim reproduction of Gillings, Mathematics in the Time of the Pharaohs, pp. 246–247. Only references to other chapters are omitted. The descriptions of problems 5, 8–9, 13, 15, 20–22 and 24 concluded with "See Chapter 12." for information on Pesu problems, the description of problem 19 concluded with "See Chapter 14." for information on linear and quadratic equations, and the descriptions of problems 10 and 14 concluded with "See Chapter 18." for information on surface areas of semicylinders or hemispheres.

References

- Clagett, Marshall. 1999. Ancient Egyptian Science: A Source Book. Volume 3: Ancient Egyptian Mathematics. Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society 232. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-232-5

- Struve V.V., (1889–1965), orientalist :: ENCYCLOPAEDIA OF SAINT PETERSBURG

- Struve, Vasilij Vasil'evič, and Boris Turaev. 1930. Mathematischer Papyrus des Staatlichen Museums der Schönen Künste in Moskau. Quellen und Studien zur Geschichte der Mathematik; Abteilung A: Quellen 1. Berlin: J. Springer

- Папирусы математические in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 1969–1978 (in Russian)

- Williams, Scott W. Egyptian Mathematical Papyri

- as given in Gunn & Peet, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 1929, 15: 176. See also, Van der Waerden, 1961, Plate 5

- Gillings, R. J. (1964), "The volume of a truncated pyramid in ancient Egyptian papyri", The Mathematics Teacher, 57 (8): 552–555, doi:10.5951/MT.57.8.0552, JSTOR 27957144,

While it has been generally accepted that the Egyptians were well acquainted with the formula for the volume of the complete square pyramid, it has not been easy to establish how they were able to deduce the formula for the truncated pyramid, with the mathematics at their disposal, in its most elegant and far from obvious form

. - Gillings, Richard J. Mathematics in the Time of the Pharaohs. Dover. pp. 246–247. ISBN 9780486243153.

Full text of the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus

- Struve, Vasilij Vasil'evič, and Boris Turaev. 1930. Mathematischer Papyrus des Staatlichen Museums der Schönen Künste in Moskau. Quellen und Studien zur Geschichte der Mathematik; Abteilung A: Quellen 1. Berlin: J. Springer

Other references

- Allen, Don. April 2001. The Moscow Papyrus and Summary of Egyptian Mathematics.

- Imhausen, A., Ägyptische Algorithmen. Eine Untersuchung zu den mittelägyptischen mathematischen Aufgabentexten, Wiesbaden 2003.

- Mathpages.com. The Prismoidal Formula.

- O'Connor and Robertson, 2000. Mathematics in Egyptian Papyri.

- Truman State University, Math and Computer Science Division. Mathematics and the Liberal Arts: Ancient Egypt and The Moscow Mathematical Papyrus.

- Williams, Scott W. Mathematicians of the African Diaspora, containing a page on Egyptian Mathematics Papyri.

- Zahrt, Kim R. W. Thoughts on Ancient Egyptian Mathematics Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine.