Mother Goose

The figure of Mother Goose is the imaginary author of a collection of French fairy tales and later of English nursery rhymes.[1] As a character, she appeared in a song, the first stanza of which often functions now as a nursery rhyme.[2] This, however, was dependent on a Christmas pantomime, a successor to which is still performed in the United Kingdom.

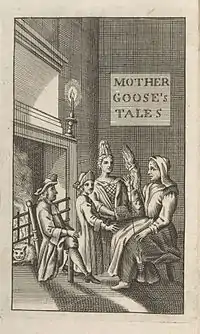

The term's appearance in English dates back to the early 18th century, when Charles Perrault's fairy tale collection, Contes de ma Mère l'Oye, was first translated into English as Tales of My Mother Goose. Later a compilation of English nursery rhymes, titled Mother Goose's Melody, or, Sonnets for the Cradle, helped perpetuate the name both in Britain and the United States.

The character

Mother Goose's name was identified with English collections of stories and nursery rhymes popularised in the 17th century. English readers would already have been familiar with Mother Hubbard, a stock figure when Edmund Spenser published the satire Mother Hubberd's Tale in 1590, as well as with similar fairy tales told by "Mother Bunch" (the pseudonym of Madame d'Aulnoy) in the 1690s.[3] An early mention appears in an aside in a versified French chronicle of weekly events, Jean Loret's La Muse Historique, collected in 1650.[4] His remark, comme un conte de la Mère Oye ("like a Mother Goose story") shows that the term was readily understood. Additional 17th-century Mother Goose/Mere l'Oye references appear in French literature in the 1620s and 1630s.[5][6][7]

Speculation about origins

In the 20th century, Katherine Elwes-Thomas theorised that the image and name "Mother Goose" or "Mère l'Oye" might be based upon ancient legends of the wife of King Robert II of France, known as "Berthe la fileuse" ("Bertha the Spinner") or Berthe pied d'oie ("Goose-Footed Bertha" ), often described as spinning incredible tales that enraptured children.[8] Other scholars have pointed out that Charlemagne's mother, Bertrada of Laon, came to be known as the goose-foot queen (regina pede aucae).[9] There are even sources that trace Mother Goose's origin back to the biblical Queen of Sheba.[10] Stories of Bertha with a strange foot (goose, swan or otherwise) exist in many languages including Middle German, French, Latin and, Italian. Jacob Grimm theorised that these stories are related to the Upper German figure Perchta or Berchta (English Bertha).[11] Like the legends of "Bertha la fileuse" in France and the story of Mother Goose Berchta was associated with children, geese, and spinning or weaving,[12] although with much darker connotations.

Despite evidence to the contrary,[13] it has been stated in the United States that the original Mother Goose was the Bostonian wife of Isaac Goose, either named Elizabeth Foster Goose (1665–1758) or Mary Goose (d. 1690, age 42).[14] She was reportedly the second wife of Isaac Goose (alternatively named Vergoose or Vertigoose), who brought to the marriage six children of her own to add to Isaac's ten.[15] After Isaac died, Elizabeth went to live with her eldest daughter, who had married Thomas Fleet, a publisher who lived on Pudding Lane (now Devonshire Street). According to Early, "Mother Goose" used to sing songs and ditties to her grandchildren all day, and other children swarmed to hear them. Finally, it was said, her son-in-law gathered her jingles together and printed them. No evidence of such printing has been found, and historians believe this story was concocted by Fleet's great-grandson John Fleet Eliot in 1860.[16]

Iona and Peter Opie, leading authorities on nursery lore, give no credence to either the Elwes-Thomas or the Boston suppositions. It is generally accepted that the term does not refer to any particular person.[17]

Nursery tales and rhymes

Charles Perrault, one of the initiators of the literary fairy tale genre, published a collection of such tales in 1695 called Histoires ou contes du temps passés, avec des moralités under the name of his son, which became better known under its subtitle of Contes de ma mère l'Oye or Tales of My Mother Goose.[18] Perrault's publication marks the first authenticated starting-point for Mother Goose stories. An English translation of Perrault's collection, Robert Samber's Histories or Tales of Past Times, Told by Mother Goose, appeared in 1729 and was reprinted in America in 1786.[19]

Nursery rhymes were once believed to have been published in John Newbery's compilation Mother Goose's Melody, or, Sonnets for the cradle[20] published some time in London in the 1760s, but the first edition was probably published in 1780 or 1781 by Thomas Carnan, Newbery's stepson and successor. Although this edition was registered with the Stationers' Company in 1780, no copy has ever been confirmed, and the earliest surviving edition is dated 1784.[21] The name "Mother Goose" has been associated in the English-speaking world with children's poetry ever since.[22]

Pantomime

_MS_Thr_847.jpg.webp)

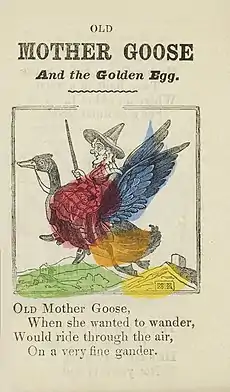

In addition to being the purported author of nursery rhymes, Mother Goose is herself the title character in one recorded by the Opies, only the first verse of which figures in later editions of their book.[23] Titled "Old Mother Goose and the Golden Egg", this verse prefaced a 15-stanza poem that rambled through a variety of adventures involving not only the egg but also Mother Goose's son Jack. There exists an illustrated chapbook omitting their opening stanza that dates from the 1820s[24] and another version was recorded by J. O. Halliwell in his The Nursery Rhymes of England (1842).[25] Other shorter versions were also recorded later.[26]

All of them, however, were dependent on a very successful pantomime first performed in London in 1806, and it is only by reference to its script that the unexplained gaps in the poem's narration are made clear.[27] The pantomime, staged at Covent Garden during the Christmas season, was the work of Thomas John Dibdin and its title, Harlequin and Mother Goose, or The Golden Egg, signals how it combines the Commedia dell'arte tradition and other folk elements with fable – in this case "The Goose That Laid the Golden Eggs".[28] The stage version became a vehicle for the clown Joseph Grimaldi, who played the part of Avaro, but there was also a shorter script for shadow pantomime which allowed special effects of a different kind.[29]

Special effects were needed since the folk elements in the story made a witch-figure of Mother Goose. In reference to this, and especially the opening stanza, illustrations of Mother Goose began depicting her as an old lady with a strong chin who wears a tall pointed hat and flies astride a goose.[9] Ryoji Tsurumi has commented on the folk aspects of this figure in his monograph on the play.[30] In the first scene, the stage directions show her raising a storm and, for the very first time onstage, flying a gander – and she later raises a ghost in a macabre churchyard scene. These elements contrast with others from the harlequinade tradition in which the old miser Avaro transforms into Pantaloon, while the young lovers Colin and Colinette become Harlequin and Columbine.

A new Mother Goose pantomime was written for the comedian Dan Leno by J. Hickory Wood in 1902. This had a different story line in which the poor but happy Mother Goose is tempted with wealth by the Devil.[31] This was the ancestor of all the pantomimes of that title that followed, adaptations of which continue to appear.[32]

Because nursery rhymes are usually referred to as Mother Goose songs in the US,[33] however, children's entertainments in which a medley of nursery characters are introduced to sing their rhymes often introduced her name into American titles. Early 20th century examples of these include A dream of Mother Goose and other entertainments by J. C. Marchant and S. J. Mayhew (Boston, 1908);[34] Miss Muffet Lost and Found : a Mother Goose play by Katharine C. Baker (Chicago, 1915);[35] The Modern Mother Goose: a play in three acts by Helen Hamilton (Chicago, 1916);[36] and the up-to-the-moment The Strike Mother Goose Settled by Evelyn Hoxie (Franklin Ohio and Denver Colorado, 1922).[37]

Sculpture

In the United States there is a granite statue of a flying Mother Goose by Frederick Roth at the entrance to Rumsey Playfield in New York's Central Park.[38] Installed in 1938, it has several other nursery rhyme characters carved into its sides.[39] On a smaller scale, there is Richard Henry Recchia's contemporary bronze rotating statue in the Rockport, Massachusetts, public library. There Mother Goose is depicted telling the tales associated with her to two small children, with twelve reliefs illustrating such stories about its round base.[40]

See also

- List of children's songs

- List of children's stories

- Luis van Rooten, Mots d'Heures: Gousses, Rames (1967)

- Thomas Fleet, published an American version of Mother Goose from stories told by his mother-in-law to his children.

References

- Macmillan Dictionary for Students Macmillan, Pan Ltd. (1981), p. 663. Retrieved 2010-7-15.

- See, for instance, item 364 in Peter and Iona Opie, The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, 1997.

- Ryoji Tsurumi, "The Development of Mother Goose in Britain in the Nineteenth Century" Folklore 101.1 (1990:28–35) p. 330 instances these, as well as the "Mother Carey" of sailor lore—"Mother Carey's chicken" being the European storm-petrel—and the Tudor period prophetess "Mother Shipton".

- Shahed, Syed Mohammad (1995). "A Common Nomenclature for Traditional Rhymes". Asian Folklore Studies. 54 (2): 307–314. doi:10.2307/1178946. JSTOR 1178946.

- Saint-Regnier (1626). Les satyres de Saint-Regnier – ... Saint-Regnier – Google Books. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- Labrosse, Guido de (21 September 2009). De la nature, vertu et utilité des plantes – Guido de Labrosse – Google Boeken. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- Pièces curieuses en suite de celles du Sieur de St. Germain – Google Boeken. 1644. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- The Real Personages of Mother Goose, Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co., 1930, p.28

- Cullinan, Bernice; Person, Diane (2001). The Continuum Encyclopedia of Children's Literature. New York: Continuum. p. 561. ISBN 978-0-8264-1516-5.

- Parker, Jeanette; Begnaud, Lucy (2004). Developing Creative Leadership. Portsmouth, NH: Teacher Ideas Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-56308-631-1.

- Grimm, J. L. C. [. w. (1882). Teutonic mythology, tr. by J.S. Stallybrass. United Kingdom: (n.p.).

- Grimm, Jacob Ludwig C. [single works]. Teutonic mythology, tr. by J.S. Stallybrass. United Kingdom, n.p, 1882.

- Benton, Joel (4 February 1899). "MOTHER GOOSE – Longevity of the Boston Myth – The Facts of History in this Matter – Review". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- [ Displaying Abstract ] (20 October 1886). "MOTHER GOOSE". THE New York Times. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- Wilson, Susan (2000). Literary Trail of Greater Boston. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 23. ISBN 0-618-05013-2.

- Hahn, Daniel; Morpurgo, Michael (1983). The Oxford Companion to Children's Literature (e-Book, Google Books). Oxford University Press. p. 400. ISBN 978-0-19-969514-0. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, Oxford University Press 1997; see the section "Mother Goose in America", pp. 36–39

- Jansma, Kimberly; Kassen, Margaret (2007). Motifs: An Introduction to French. Boston, MA: Thomson Higher Education. p. 456. ISBN 978-1-4130-2810-2.

- Charles Francis Potter, "Mother Goose", Standard Dictionary of Folklore, Mythology, and Legends II (1950), p. 751f.

- "Mother Goose's melody: Prideaux, William Francis, 1840–1914". Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- Nigel Tattersfield in Mother Goose's melody ... (a facsimile of an edition of c. 1795, Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2003).

- Driscoll, Michael; Hamilton, Meredith; Coons, Marie (2003). A Child's Introduction Poetry. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-57912-282-9.

- The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, pp. 373–4]

- Available as a PDF from Toronto Public Library

- Google Books, pp.32-4

- "Diploma thesis" (PDF).

- Jeri Studebaker, Breaking the Mother Goose Code, Moon Books 2015, Chapter 6

- Dibdin, Thomas. Harlequin and Mother Goose; or, the golden egg! A comic pantomime. London: Thomas Hailes Lacy. hdl:2027/iau.31858004934059.

- "Mother Goose; or, Harlequin and the Golden Egg: an original shadow pantomime". 21 August 1864 – via Google Books.

- Ryoji Tsurumi (1990) "The Development of Mother Goose in Britain in the Nineteenth Century", Folklore 101:1, pp.28-35

- Caroline Radcliffe, p. 127–9 "Dan Leno, Dame of Drury Lane" in Victorian Pantomime: A Collection of Critical Essays, Palgrave Macmillan 2010

- Michael Billington's Mother Goose review, The Guardian, 12 Dec. 2016

- The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, p. 1

- Marchant, J. C.; Mayhew, S. J.; et al. (21 August 1908). A dream of Mother Goose and other entertainments. Boston: Walter H. Baker. hdl:2027/hvd.hxdltb.

- "Miss Muffet lost and found: a Mother Goose play". 21 August 1915 – via Hathi Trust.

- "The modern Mother Goose ..: Hamilton, Helen. [old catalog heading]: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming". Internet Archive. Chicago, Rand McNally & Co. 1916.

- "The strike Mother goose settled ..: Hoxie, Evelyn. [from old catalog]: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming". Internet Archive. Franklin, Ohio, Eldridge Entertainment House. 1922.

- Raymond Carroll, The Complete Illustrated Map and Guidebook to Central Park, Sterling Publishing Company, 2008, p. 26

- Illustrations at Central Park in Bronze

- "Mother Goose genius design"

External links

- 1904 Facsimile of earliest American compilation, John Newberry's Mother Goose's Melody, 1791 edition

- "Who was Mother goose?"

- At Project Gutenberg:

- The Tales of Mother Goose by Charles Perrault translated by Charles Welsh

- The Real Mother Goose illustrated by Blanche Fisher Wright

- The Only True Mother Goose Melodies (Anonymous)

- Mother Goose in Prose by L. Frank Baum

Mother Goose public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Mother Goose public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Mother Goose Clip Art Public domain illustrations of Mother Goose rhymes

- Collection of Mother Goose verses

- Verses with artwork and audio recordings

- Play and education with Mother Goose nursery rhymes

- Earliest extant evidence of an American Mother Goose in 1691

- Illustrated Editions of Traditional Mother Goose Rhymes: A Bibliographical Listing