Mozart family grand tour

The Mozart family grand tour was a journey through western Europe, undertaken by Leopold Mozart, his wife Anna Maria, and their musically gifted children Maria Anna (Nannerl) and Wolfgang Theophilus (Wolferl) from 1763 to 1766. At the start of the tour the children were aged eleven and seven respectively. Their extraordinary skills had been demonstrated during a visit to Vienna in 1762, when they had played before the Empress Maria Theresa at the Imperial Court. Sensing the social and pecuniary opportunities that might accrue from a prolonged trip embracing the capitals and main cultural centres of Europe, Leopold obtained an extended leave of absence from his post as deputy Kapellmeister to the Prince-Archbishopric of Salzburg. Throughout the subsequent tour, the children's Wunderkind status was confirmed as their precocious performances consistently amazed and gratified their audiences.

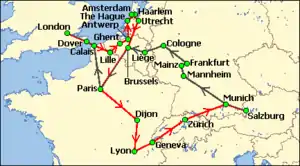

The first stage of the tour's itinerary took the family, via Munich and Frankfurt, to Brussels and then on to Paris where they stayed for five months. They then departed for London, where during a stay of more than a year Wolfgang made the acquaintance of some of the leading musicians of the day, heard much music, and composed his first symphonies. The family then moved on to the Netherlands, where the schedule of performances was interrupted by the illnesses of both children, although Wolfgang continued to compose prolifically. The homeward phase incorporated a second stop in Paris and a trip through Switzerland, before the family's return to Salzburg in November 1766.

The material rewards of the tour, though reportedly substantial, did not transform the family's lifestyle, and Leopold continued in the Prince-Archbishop's service. However, the journey enabled the children to experience to the full the cosmopolitan musical world, and gave them an outstanding education. In Wolfgang's case this would continue through further journeys in the following six years, prior to his appointment by the Prince-Archbishop as a court musician.

Child prodigies

The Mozart children were not alone as 18th-century music prodigies. Education writer Gary Spruce refers to hundreds of similar cases, and cites that of William Crotch of Norwich who in 1778, at the age of three, was giving organ recitals.[1] British scholar Jane O'Connor explains the 18th century fascination with prodigies as "the realisation of the potential entertainment and fiscal value of an individual child who was in some way extraordinary".[2] Other childhood contemporaries of Mozart included the violinist and composer Thomas Linley, born the same year as Wolfgang, and the organist prodigy Joseph Siegmund Bachmann.[3][4] Mozart eventually became recognised among prodigies as the future standard for early success and promise.[5]

Of seven children born to Leopold and Anna Maria Mozart, only the fourth, Maria Anna (Nannerl), born 31 July 1751, and the youngest, Wolfgang, born 27 January 1756, survived infancy.[6] The children were educated at home, under Leopold's guidance, learning basic skills in reading, writing, drawing and arithmetic, together with some history and geography.[7] Their musical education was aided by exposure to the constant rehearsing and playing of Leopold and his fellow musicians.[7] When Nannerl was seven her father began to teach her to play the harpsichord, with Wolfgang looking on; according to Nannerl's own account "the boy immediately showed his extraordinary, God-given talent. He often spent long periods at the clavier, picking out thirds, and his pleasure showed that they sounded good to him... When he was five years old he was composing little pieces which he would play to his father who would write them down".[8] A family friend, the poet Johann Andreas Schachtner, recounted that at the age of four Wolfgang began to compose a recognisable piano concerto, and was able to demonstrate a phenomenal sense of pitch.[7]

Nannerl herself was an apt pupil, no less quick to learn than her brother, and was playing the keyboard with striking virtuosity by the time she was eleven.[9] In that year, 1762, Leopold brought the children to Munich to play before Maximilian III Joseph, Elector of Bavaria.[10] Leopold then took the entire family to Vienna, on a trip that lasted for three months.[11] He had secured invitations from several noble patrons, and within three days of arriving the children were playing at the palace of Count Collalto. Among those present was the Viennese Treasury councillor and future prime minister Karl von Zinzendorf, who noted in his diary that "a little boy, said to be only five-and-a-half years old [Wolfgang was actually nearly seven], played the harpsichord".[11] After an appearance before the Imperial Vice-Chancellor, the Mozarts were invited to the royal court, where the Empress Maria Theresa tested Wolfgang's abilities by requiring him to play with the keyboard covered.[11] During this court visit Wolfgang met the Archduchess Maria Antonia, the future Queen Marie Antoinette of France, who was two months his senior. Mozart's biographer Eric Blom recounts an anecdote of how the Archduchess helped Wolfgang when he slipped on the polished floor; she is supposed to have received a proposal of marriage in return.[12]

As the Mozarts began to be noticed by the Viennese aristocracy, they were often required to give several performances during a single day.[11] They were well rewarded for this activity—at the end of their first hectic week in Vienna, Leopold was able to send home the equivalent of more than two years' salary.[13] Their schedule was interrupted when Wolfgang fell ill with scarlet fever, and their former momentum was not regained. Nevertheless, the visit left Leopold eager to pursue further opportunities for social and financial success.[13] On their return to Salzburg, Wolfgang played the harpsichord and violin at a birthday concert for the archbishop, to the evident astonishment of those present.[14]

Grand tour

Preparations

In a letter to his friend and landlord Johann Lorenz Hagenauer (1712–1792), a prominent Salzburg merchant, written after the tour, Leopold quotes the German diplomat Friedrich Melchior, Baron von Grimm, who after hearing the children play had said: "Now for once in my life I have seen a miracle: this is the first".[15] Leopold believed that it was his duty to proclaim this miracle to the world, otherwise he would be "the most ungrateful creature".[15] He was said to have described Wolfgang as "The miracle which God let be born in Salzburg."[16] Mozart biographer Wolfgang Hildesheimer has suggested that, at least in the case of Wolfgang, this venture was premature: "Too soon, [the] father dragged [the] son all over Western Europe for years. This continual change of scene would have worn out even a robust child..."[17] However, there is little evidence to suggest that Wolfgang was physically harmed or musically hindered by these childhood exertions; it seems that he felt equal to the challenge from the start.[18]

Leopold wanted to begin the tour as soon as possible—the younger the children were, the more spectacular would be the demonstration of their gifts.[15] The route he intended to take included southern Germany, the Austrian Netherlands, Paris, Switzerland and possibly northern Italy. The London leg was only added after urgings during the Paris visit, and the eventual Dutch trip was an unplanned detour.[15][19] The plan was to take in as many princely European courts as possible, as well as the great cultural capitals—Leopold was relying on his professional musical network and on his more recent social contacts to obtain invitations from the royal courts. Practical assistance came from Hagenauer, whose trading connections in the major cities would supply the Mozarts with what were effectively banking facilities.[13] These would enable them to obtain money en route, while waiting for the proceeds from their performances to accumulate.[20]

Wolfgang prepared for the tour by perfecting himself on the violin, which he had learned to play apparently without any tutelage whatsoever.[21] As for more general preparation, the children delighted in making music together, something they never lost.[22] On tour, even during the busiest travelling days they would fit in their daily practice, appearing to thrive on the hectic schedule.[23] Before the journey could begin, Leopold needed the consent of his employer, the prince-archbishop. Leopold had only been appointed deputy Kapellmeister in January 1763; nevertheless the archbishop's consent to an extended leave of absence was granted, on the grounds that the Mozarts' successes would bring glory to Salzburg, its ruler, and to God.[15]

Early stages (July–November 1763)

.jpg.webp)

The journey's beginning, on 9 July 1763, was inauspicious; on the first day a carriage wheel broke, requiring a 24-hour pause while repairs were carried out. Leopold turned this delay to advantage by taking Wolfgang to the nearby church at Wasserburg, where according to Leopold the boy played on the organ pedalboard as if he had been studying it for months.[24] In Munich, on successive evenings, the children played before Elector Maximilian III, earning from these engagements the equivalent of half of Leopold's annual salary of 354 florins.[25][26][27] The next stop was Augsburg, where Leopold's estranged mother refused to attend any of the three concerts given there.[28] The family then moved on to Schwetzingen and the Mannheim court, where the children's performance apparently amazed Elector Palatine Karl Theodor and his Electress.[26]

The next extended stop was at Mainz. The Elector was ill, but the Mozarts gave three concerts in the town, which brought in 200 florins.[29] From Mainz the family took the market boat up the River Main to Frankfurt, where several public concerts were given. Among those present at the first of these was the fourteen-year-old Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who would many years later recall "the little fellow with his wig and his sword".[26] An advertisement for these concerts announced that "the girl" would play "the most difficult pieces by the greatest masters", while "the boy" would play a concerto on the violin and also repeat his Vienna trick of playing with the keyboard completely covered by a cloth. Finally, "he will improvise out of his head, not only on the fortepiano but also on the organ...in all the keys, even the most difficult, that he may be asked".[26]

The family proceeded by riverboat to Koblenz, Bonn and Cologne. Turning west they reached Aachen, where a performance was given before Princess Anna Amalia of Prussia, the sister of Frederick the Great.[14] The princess tried to persuade Leopold to abandon his itinerary and go to Berlin, but Leopold resisted. "She has no money", he wrote to Hagenauer, recounting that she had repaid the performance with kisses. "Howbeit, neither mine host nor the postmaster are to be contented with kisses."[30] They proceeded into the Austrian Netherlands, an area corresponding roughly to present-day Belgium and Luxembourg,[31] where they arrived in the regional capital, Brussels, on 5 October. After several weeks' waiting for the governor-general, Prince Charles of Lorraine, to summon them ("His highness the prince does nothing but hunt, gobble and swill", wrote Leopold to Hagenauer),[30] the Mozarts gave a grand concert in the prince's presence on 7 November. On the 15th the family departed for Paris.[26]

During the hiatus in Brussels, Wolfgang turned his attention briefly from performing to composing. On 14 October he finished an Allegro for harpsichord, which would later be incorporated into the C major sonata, K. 6, which he completed in Paris.[26]

Paris (November 1763 – April 1764)

On 18 November 1763 the Mozart family arrived in Paris, one of the most important musical centres of Europe, and also a city of great power, wealth, and intellectual activity.[32] Leopold hoped to be received by the court of Louis XV at nearby Versailles. However, a recent death in the royal family prevented any immediate invitation, so Leopold arranged other engagements.[32] One person who took particular note of the children was the German diplomat Friedrich Melchior von Grimm, whose journal records Wolfgang's feats in glowing terms: "the most consummate Kapellmeister could not be more profound in the science of harmony and modulation".[32] Leopold's own assessment, written a few months later, was similarly effusive: "My little girl, although only 12 years old, is one of the most skilful players in Europe and, in a word, my boy knows more in his eighth year than one would expect for a man of forty".[33][34]

On 24 December the family moved to Versailles for two weeks during which, through a court connection, they were able to attend a royal dinner, where Wolfgang was reportedly allowed to kiss the hand of the Queen.[32] At Versailles they also visited the famous courtesan Madame de Pompadour, then in the last months of her life—"an extremely haughty woman who still ruled over everything", according to Leopold.[35] In Nannerl's later recollections, Wolfgang was made to stand on a chair to be examined by the Madame, who would not allow him to kiss her.[36]

.jpg.webp)

Mozart did play some instruments at Versailles for the royal family,[37] although there is no record of him or the children giving a formal concert at Versailles. In February 1764 they were given 50 louis d'or (about 550 florins) and a gold snuff-box by the royal entertainments office, presumably for entertaining the royal family privately, but no more details are available.[32] Further concerts were given in Paris on 10 March and on 9 April, at a private theatre in the rue et Porte St Honoré.[32] At the same time Wolfgang's first published works were printed: two pairs of sonatas for harpsichord and violin, K. 6 and 7, and K. 8 and 9. These pairs became Opus 1 and Opus 2 in Leopold's private catalogue of his son's work.[33] The first pair was dedicated to the king's daughter, Madame Victoire de France, the second to the Countess of Tessé. Mozart biographer Stanley Sadie comments that some aspects of these pieces are rather childish and naïve, but that nevertheless their technique is "astonishingly sure, their line of thinking is clear and smooth, and their formal balance is beyond reproach".[38]

A decision was taken in Paris to go to London, perhaps on the advice of Leopold's musical and court acquaintances, who would probably have advised him that England was, in the words of the Mozart scholar Neal Zaslaw, "known for the enthusiasm with which it received continental musicians and the extravagance with which it rewarded them".[39] On 10 April the family left for Calais and after an unpleasant crossing to Dover on a hired boat, and some delays, arrived in London on 23 April.[40]

London (April 1764 – July 1765)

The Mozarts' first London lodgings were above a barber's shop in Cecil Court, near St Martin-in-the-Fields. Letters of introduction from Paris proved effective; on 27 April 1764, four days after their arrival, the children were playing before King George III and his 19-year-old German queen, Charlotte Sophia.[41] A second royal engagement was fixed for 19 May,[42] at which Wolfgang was asked by the king to play pieces by Handel, Johann Christian Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel. He was allowed to accompany the queen as she sang an aria, and he later improvised on the bass part of a Handel aria from which, according to Leopold, he produced "the most beautiful melody in such a manner that everyone was astonished".[41][43]

Many of the nobility and gentry were leaving town for the summer, but Leopold reckoned that most would return for the king's birthday celebrations on 4 June, and accordingly organised a concert for the 5th.[44] This was deemed a success, and Leopold hastened to arrange for Wolfgang to appear at a benefit concert for a maternity hospital on 29 June, at Ranelagh Pleasure Gardens. Leopold apparently saw this effort to support charitable works as "a way to earn the love of this very special nation".[44] Wolfgang was advertised as "the celebrated and astonishing Master Mozart, a Child of Seven Years of Age..." (he was in fact eight), "justly esteemed the most extraordinary Prodigy, and most amazing Genius, that has appeared in any Age".[45] On 8 July there was a private performance at the Grosvenor Square home of the Earl of Thanet, from which Leopold returned with an inflammation of the throat and other worrying symptoms.[44] "Prepare your heart to hear one of the saddest events", he wrote to Hagenauer in anticipation of his own imminent demise.[46] He was ill for several weeks, and for the sake of his health the family moved from their Cecil Court lodgings to a house in the countryside, at 180 Ebury Street, then considered part of the village of Chelsea.[47]

During Leopold's illness performances were impossible, so Wolfgang turned to composition. According to the writer and musician Jane Glover, Wolfgang was inspired to write symphonies after meeting Johann Christian Bach.[47] It is not clear when this meeting occurred, or when Wolfgang first heard J. C. Bach's symphonies, although he had played the older composer's harpsichord works in his May 1764 royal recital.[48] Wolfgang soon completed his Symphony No. 1 in E flat, K. 16, and started his No. 4 in D major, K. 19 (which Zaslaw concludes was more likely composed, or at least completed, in The Hague).[49][50] The D major symphony has, in Hildesheimer's words, "an originality of melody and modulation which goes beyond the routine methods of his [grown-up] contemporaries".[51] These are Wolfgang's first orchestral writings, although Zaslaw hypothesises a theoretical "Symphony No. 0" from sketches in Wolfgang's musical notebook.[52] Three lost symphonies, identified in the Köchel catalogue of Mozart's works only by their incipits (first few bars of music), may also have originated from the London period.[34] Other works composed by Wolfgang in London include several instrumental sonatas, the jewel of which, according to Hildesheimer, is the C major sonata for piano, four hands, K. 19d.[53] A set of violin sonatas, with extra flute and cello parts, was dedicated to Queen Charlotte at her request, and presented to her with an appropriate inscription in January 1765.[54] Wolfgang also wrote his first vocal works, the motet "God is our Refuge", K. 20, and the tenor aria Va, dal furor portata, K. 21.[55] At the end of September, with Leopold's recovery, the family moved back to central London, to lodgings in Thrift Street (later 20 Frith Street), Soho. These lodgings were located conveniently close to several concert rooms, and to the residences of both J. C. Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel. Bach, a son of Johann Sebastian Bach, soon became a family friend; Nannerl later recalled Bach and the eight-year-old Wolfgang playing a sonata together, taking turns to play a few bars individually, and that "anyone not watching would have thought it was played by one person alone".[56] There is no record that the Mozarts met Abel, but Wolfgang knew his symphonies, perhaps through the medium of the annual Bach-Abel concert series, and was much influenced by them.[57]

On 25 October, at King George's invitation, the children played at the celebrations marking the fourth anniversary of the king's accession.[58] Their next public appearance was a concert on 21 February 1765, before a moderate audience—the date clashed with a Bach-Abel concert. Only one more London concert was given, on 13 May at Hickford's Long Room, but between April and June members of the public could go to the Mozarts' lodgings where, for a five shilling fee, Wolfgang would perform his musical party pieces.[59] During June both the "young Prodigies"[60] performed daily at the Swan and Harp Tavern in Cornhill, the charge this time being a mere two shillings and sixpence. These were, as Sadie puts it, "Leopold's last, desperate effort to extract guineas from the English public".[61] Hildesheimer likens this part of the tour to a travelling circus, comparing the Mozarts to a family of acrobats.[17]

The Mozarts left London for the continent on 24 July 1765. Before this, Leopold allowed Wolfgang to be subjected to a scientific examination, conducted by The Hon. Daines Barrington. A report, issued in Philosophical Transactions for the year 1770, confirms the truth of Wolfgang's exceptional capabilities.[62] Practically the last act of the family in London was the gift to the British Museum of the manuscript copy of "God is our refuge".[62]

The Netherlands (September 1765 – April 1766)

Leopold had been specific in letters to Hagenauer that the family would not visit the Dutch Republic, but would go to Paris and then return home to Salzburg.[49] However, he was persuaded by an envoy of the Princess Carolina of Orange-Nassau, sister of the Prince of Orange, to go instead to The Hague and to present the children to her, as official guests of the court.[49] After the party's landing at Calais there was a month's delay at Lille, as first Wolfgang fell sick with tonsillitis, then Leopold suffered prolonged dizziness attacks.[63] Early in September the family moved on to Ghent, where Wolfgang played on the new organ at the Bernardines chapel; a few days later he played on the cathedral organ at Antwerp.[64] On 11 September the family finally reached The Hague.[63]

After arriving in The Hague, Nannerl developed a severe cold and was unable to participate in the initial concerts before the Princess during their first week, nor in a performance before the Prince a few days later.[63] Leopold was sufficiently confident of Nannerl's recovery to announce the appearances of both prodigies at a concert to be given at the hall of the Oude Doelen on 30 September. The notice for this concert gives Wolfgang's age as eight (he was nine), but correctly gives Nannerl's as fourteen. The advertisement concentrates on Wolfgang: "All the overtures will be from the hands of this young composer [...] Music-lovers may confront him with any music at will, and he will play it at sight".[49] It is not certain whether this concert in fact took place—Sadie believes it may have been postponed.[63] If it did happen, Wolfgang appeared alone, for by this time Nannerl's cold had turned into typhoid fever. Her condition grew steadily worse, and on 21 October she was given the last sacrament.[63] A visit from the royal physician turned the tide; he changed the treatment, and by the end of the month she was recovering. Then Wolfgang fell ill, and it was mid-December before he was on his feet again.[63]

Both children were able to appear at the Oude Doelen on 22 January 1766, in a concert which may have included the first public performance of one of Wolfgang's London symphonies, K. 19, and possibly of a new symphony in B flat major K. 22, composed in the Netherlands.[65] Following this concert they spent time in Amsterdam before returning to The Hague early in March.[63] The main reason for their return was the forthcoming public celebrations of the Prince of Orange's coming of age. Wolfgang had composed a quodlibet (song medley) for small orchestra and harpsichord, entitled Gallimathias musicum, K. 32, which was played at a special concert to honour the Prince on 11 March.[66] This was one of several pieces composed for the occasion; Wolfgang also wrote arias for the Princess using words from Metastasio's libretto Artaserse (including Conservati fedele, K. 23), and keyboard variations on a Dutch song Laat ons juichen, Batavieren! K. 24. He wrote a set of keyboard and violin sonatas for the Princess, as he had earlier for the French princess and for the Queen of Great Britain. Another symphony, K. 45a, commonly known as "Old Lambach" and once thought to have been written several years later, was also written in The Hague, possibly for the Prince's coming-of-age concert.[63][67]

The family left The Hague at the end of March, moving first to Haarlem, where the organist of St Bavo's Church invited Wolfgang to play on the church's organ, one of the largest in the country.[63] From there they traveled east and south, giving concerts along the way at Amsterdam and Utrecht at 21 April, before leaving the Netherlands and traveling through Brussels and Valenciennes, to arrive in Paris on 10 May.[63]

Homeward journey (April–November 1766)

The family remained in Paris for two months. No concerts were given by them in this period although, according to Grimm, there were performances of Wolfgang's symphonies.[68] Grimm was effusive about the development of both children; Nannerl, he wrote, "had the finest and most brilliant execution on the harpsichord", and: "no-one but her brother can rob her of supremacy".[69] Of Wolfgang he quoted a Prince of Brunswick as saying that many Kapellmeisters at the peak of their art would die without knowing what the boy knew at the age of nine. "If these children live," wrote Grimm, "they will not remain in Salzburg. Monarchs will soon be disputing about who should have them."[69]

The only surviving music composed by Wolfgang during this Paris visit is his Kyrie in F major, K. 33, his first attempt to write formal church music.[70] On 9 July, the family left Paris for Dijon, following an invitation from the Prince of Conti. The children played in a concert there on 19 July, accompanied by a local orchestra, about whose players Leopold made disparaging comments: Très médiocre – Un misérable italien détestable – Asini tutti – Un racleur (a scratcher) – Rotten.[71] They moved on to Lyon where Wolfgang "preluded for an hour and a quarter with the most capable master here, yielding nothing to him".[72]

A letter to Hagenauer dated 16 August indicated that Leopold wished to proceed to Turin, then across northern Italy to Venice, and home via the Tyrol. "Our own interest and love of travel should have induced us to follow our noses", he wrote, but added: "...I have said I shall go [directly] home and I shall keep my word."[73] The family took a shorter route through Switzerland, arriving in Geneva on 20 August, where the children gave two concerts, and were received by the distinguished composer André Grétry. Many years later Grétry wrote of this encounter: "I wrote for him [Wolfgang] an Allegro in E flat, difficult but without pretension; he played it, and everyone, except myself, thought it was a miracle. The child had never broken off, but following the modulations, he had substituted a number of passages for those I had written."[73] This claim, that Wolfgang improvised when faced with passages he could not play, appears to be the only adverse comment from all those called upon to test him.[73]

The journey through Switzerland continued, with concerts at Lausanne and Zürich. Since leaving the Netherlands, Wolfgang had composed little; a minor harpsichord piece, K. 33B, written for the Zürich concerts, and later some cello pieces (since lost) written for the Prince of Fürstenberg. The prince received the party on 20 October, on its arrival in Donaueschingen on the German border, for a stay of some 12 days.[73] Resuming their journey, they reached Munich on 8 November. They were delayed here for nearly two weeks after Wolfgang fell ill, but he was well enough to perform before the Elector, with Nannerl, on 22 November.[73] A few days later they set out for Salzburg, arriving at their home on the Getreidegasse on 29 November 1766.[73]

Evaluation

Financial

The party had survived major setbacks, including several prolonged illnesses which had curtailed their earning powers. Although Leopold did not reveal the full extent of the tour's earnings, or its expenses,[74] the material benefits from the tour had evidently been considerable—but so had the costs. The librarian of St Peter's Abbey, Salzburg, thought that the gifts ("gewgaws") alone which they brought back were worth about 12,000 florins, but estimated the total costs of the enterprise at 20,000 florins.[75] The expenses were certainly high; in a letter to Hagenauer sent in September 1763, after ten weeks on the road, Leopold reported expenses to date as 1,068 florins, an amount covered by their concert earnings without, however, any significant surplus.[76] Leopold stated that "there was nothing to be saved, because we have to travel in noble or courtly style for the preservation of our health and the reputation of my court."[76] He later recorded that on arrival in Paris in November 1763 that they had "very little money".[77]

At times, the coffers were full; in April 1764, near the end of the Paris sojourn and after two successful concerts, Leopold announced he would shortly be depositing 2,200 florins with his bankers.[78] Two months later, after the initial London successes, Leopold banked a further 1,100 florins. However, in November of that year, after his illness and with uncertain earning prospects, he was worrying about the high costs of living in London—he informed Hagenauer that he had spent 1,870 florins in the four-month period since July.[79] The following summer, after little concert activity, Leopold resorted to increasingly desperate measures[80] to raise funds, including the children's daily circus performances at the Swan and Harp Inn at prices described by Jane Glover as humiliating.[80] The insecurity of travelling life led Leopold to believe, later, that Wolfgang was not worldly-wise enough to attempt such journeys alone, and needed to be anchored to an assured salary.[81]

Musical

In terms of musical development, while both children had advanced, Wolfgang's progress had been extraordinary, beyond all expectation.[74] The Mozarts were now known throughout the musical establishments and royal courts of Northern Europe.[74] As well as the encounters in palaces with kings, queens and nobility, the children could converse in several languages;[74] the tour represented, for them, an outstanding education.[18] However, these advantages had been gained at a price; Grimm, in Paris, noting the stress and strain on Wolfgang in particular, had feared that "so premature a fruit might fall before maturing".[74] However, Hildesheimer, while also expressing concerns, concludes that if Mozart's death at the age of 35 was caused by the exertions of his childhood, the intervening decades would not have been so productive, and obvious symptoms of decline would have manifested themselves.[18]

Of Wolfgang's music composed during the tour, around thirty pieces survive. A number of works are lost, including the Zürich cello pieces and several symphonies.[82] The surviving works include the keyboard sonatas written in Paris, London and The Hague, four symphonies, various arias, the assorted music written for the Prince of Orange, a Kyrie, and other minor pieces.[83][84] Mozart's career as a symphonist began in London where, in addition to the direct influences of Abel and J.C. Bach, he would have heard symphonies from leading London composers including Thomas Arne, William Boyce and Giuseppe Sammartini—"a nearly ideal introduction to the genre", according to Zaslaw.[34] The earliest symphonies, Zaslaw points out, while not in the same class as the later Mozart masterpieces, are comparable in length, complexity and originality to those written at the same time by the acknowledged symphonic masters of the day.[85] Indeed, Abel's Symphony No. 6 in E Flat was similar enough in style and technique to be mistaken as Mozart's, and is listed as such (Symphony No. 3, K. 18) in the original Köchel catalogue.[86] Sadie observes that the K. 22 symphony composed in The Hague is a good deal more sophisticated than the earlier ones which were written in London.[87]

Mozart's creative progress is likewise reflected in the sonatas composed for the Princess of Orange, which, according to Sadie, mark a considerable advance in technique and ideas over the earlier Paris and London sets.[87] The arias composed in the Netherlands include Mozart's first attempts at "aria d'affetto", Per pièta, bell'idol mio, K. 73b, once thought to have been composed much later, as its higher K number indicates.[88] The tour thus saw Wolfgang's transformation from a composer of simple keyboard pieces to one with increasing mastery over a range of genres. This was evidenced in his home city, on 8 December, when one of his symphonies (it is uncertain which) was performed at High Mass at Salzburg Cathedral.[89][90] Leopold's employer, the Prince-Archbishop, was frankly sceptical about Wolfgang's compositions, believing them to be Leopold's because they were "not nearly bad enough to be the work of a child".[91]

Aftermath

Whatever the true extent of their financial rewards from the tour, the Mozart family continued to live in their cramped apartment on the Getreidegasse, while Leopold resumed his duties as a court musician.[92] However, travel and public display dominated the next six years of Wolfgang's life. In September 1767 the family was on the move again, this time to Vienna, remaining there (apart from an enforced evacuation during a smallpox epidemic) until January 1769.[93] In December of the same year Leopold and Wolfgang left for Italy—without Nannerl who, now 18, was no longer exhibitable as a child wonder.[94] They were away for sixteen months, and returned to Milan in August 1771 for five months, to attend rehearsals and the performance of Wolfgang's opera Ascanio in Alba.[95] A third and final visit to Italy, from October 1772 until March 1773, was the last of the extended trips; the new Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg, Hieronymous Colloredo, had distinct views about the roles of his court musicians, which precluded the freedoms that Leopold—and now Wolfgang, himself employed by the court[96]—had formerly enjoyed.[97]

See also

Notes and references

- Spruce, p. 71

- O'Connor, pp. 40–41

- Sadie, p. 102

- Sadie, pp. 192–93

- Knittel, p. 124

- The full baptismal names of these children were Maria Anna Walburgia Ignatia and Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus. Maria Anna was always known by the diminutive "Nannerl", while the boy's name was in his usage later Wolfgang Amadé (or Amadè). The form "Wolfgang Amadeus", occasionally used in his lifetime, has become popularised since. Theophilus and Amadeus are respectively the Greek and Latin forms of "Loved of God". Sadie, pp. 15–16

- Glover, pp. 16–17

- Sadie, p. 18

- Blom, p. 8

- Sadie, p. 22, casts doubt on this visit, suggesting that it might have been "falsely remembered" by Nannerl.

- Sadie, pp. 23–29

- Blom, p. 14. Gutman, Introduction p. xx, has the same story. See also Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette

- Glover, pp. 18–19

- Kenyon, p. 55

- Sadie, pp. 34–36

- "Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | Biography, Facts, & Works". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- Hildesheimer, pp. 30–31

- Hildesheimer, p. 29

- Blom, p. 23

- Halliwell, p. 67

- Blom, p. 14

- Glover, p. 19

- Halliwell, p. 56

- Leopold Mozart letter, quoted by Sadie, p. 37

- The florin, or (German: gulden) was the currency of the Austro-Hungarian empire. A florin was worth about one-tenth of a £ sterling.

- Sadie, pp. 37–47

- Sadie, p. 35

- Glover, p. 20

- Sadie, p. 41

- Blom, p. 17

- Sadie, p. 46

- Sadie, pp. 47–50

- Kenyon, p. 56

- Zaslaw, pp. 28–29

- Baker, p. 22

- Blom, p. 19

- "Visit from the child Mozart, 1763–1764". Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- Sadie, p. 57

- Zaslaw, p. 42

- Sadie, pp. 58–59

- Sadie, pp. 58–60

- Zaslaw dates this second royal recital 28 May – Zaslaw, p. 26

- Blom, pp. 23–24

- Blom, p. 25

- Sadie, p. 62

- Sadie, pp. 63–65

- Glover, p. 25

- Zaslaw, pp. 25–26

- Zaslaw, pp. 44–45

- The symphonies numbered 2, K. 17 and 3, K. 18 are each spurious. No. 2 is the work of Leopold, No. 3 of Carl Friedrich Abel. Blom, p. 26

- Hildesheimer, pp. 34–35

- Zaslaw, pp. 17–20

- Hildesheimer, p. 33

- Sadie, p. 86

- Blom, p. 26

- Sadie, p. 66

- Gutman, p. 184 (f/n)

- Blom, p. 27

- "Mozart in London". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. 26 April 1864. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

[reprints from London paper, probably Public Advertisor:] 'For the Benefit of Miss Mozart of Thirteen, and Master Mozart of Eight Years of Age, Prodigies of Nature. Hickford's Great Room in Brewer Street, 'This Day, May 13, wille A Concert of Vocal and Instrumental Music, with all the Overtures of this little Boy's own Composition...(13th May, 1765)'... 'Mr. Mozart, the Father of the celebrated young Musical Family...takes the time to inform the public that he has taken the great Room in the Swan and Hoop Tavern in Cornhill, where he will give an Opportunity to all the Curious to hear these two young Prodigies perform every day from Twelve to Three. (8th July, 1765)'

- Sadie, p. 72

- Sadie, p. 69

- Sadie, pp. 75–78

- Sadie, pp. 90–95

- Blom, p. 30

- Zaslaw, pp. 47–51

- Zaslaw, pp. 52–55

- Zaslaw, p. 64

- Zaslaw, pp. 64–66

- Sadie, pp. 96–99

- Blom. p. 32

- Zaslaw, p. 67. The other terms may be translated: très mediocre, "very undistinguished"; Un misérable italien détestable, "a repulsive Italian misery"; Asini tutti, "all idiots"; and Rotten, "inadequate".

- Quoted by Sadie, p. 99, from a contemporary report

- Sadie, pp. 99–103

- Glover, p. 26

- Sadie, p. 111

- Halliwell, p. 55

- Halliwell, p. 61

- Halliwell, p. 64

- Halliwell, p. 85

- Glover, p. 24

- Halliwell. p. 63

- Zaslaw, pp. 29–31

- Sadie, pp. 613–21 (summary of Köchel catalogue)

- "Köchel's catalogue of Mozart's works". Classical.net. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- Zaslaw, p. 35

- Sadie, p. 82. A similar misunderstanding arose over a symphony of Leopold's which Köchel called Symphony No 2, K. 17

- Sadie, pp. 104–08

- "Aria d'affeto" refers to arias of the slow, expressive type, such as "Dove sono" in Figaro or "Per pièta, ben mio, perdona" from Così fan tutte. Sadie, p. 108

- Zaslaw, p. 70

- Sadie, pp. 111–12

- Blom, p. 34

- Glover, p. 28

- Kenyon, p. 61

- Sadie, p. 176

- Kenyon, p. 64

- He had been made a concert master with a salary of 150 florins. Blom, p. 60

- Kenyon, p. 65

Sources

- Baker, Richard (1991). Mozart: An Illustrated Biography. London: Macdonald and Co. ISBN 0-356-19695-X.

- Blom, Eric (1935). 'Mozart' (Master Musicians series). London: J. M. Dent.

- Glover, Jane (2005). Mozart's Women. London: Macmillan. ISBN 1-4050-2121-7.

- Chrissochoidis, Ilias. "London Mozartiana: Wolfgang's disputed age & early performances of Allegri's Miserere", The Musical Times, vol. 151, no. 1911 (Summer 2010), 83–89.

- Gutman, Robert W. (1999). Mozart: A Cultural Biography. San Diego: Harcourt Inc. ISBN 0-15-601171-9.

- Halliwell, Ruth (1998). The Mozart Family: Four Lives in a Social Context. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816371-1.

- Hildesheimer, Wolfgang (1985). Mozart. London: J. M. Dent. ISBN 0-460-02401-9.

- Kenyon, Nicholas (2006). The Pegasus Pocket Guide to Mozart. New York: Pegasus Books. ISBN 1-933648-23-6.

- Knittel, K.M. (2001). "The Construction of Beethoven". The Cambridge History of Nineteenth Century Music, ed. Samson, Jim. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59017-5.

- O'Connor, Jane (2008). The Cultural Significance of the Child Star. London: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-96157-8.

- Sadie, Stanley (2006). Mozart: The Early Years, 1756–1781. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-06112-4.

- Spruce, Gary (1996). Teaching Music. London: RoutledgeFalmer. ISBN 0-415-13367-X.

- Zaslaw, Neal (1991). Mozart's Symphonies: Context, Performance Practice, Reception. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-816286-3.

- "Köchel's catalogue of Mozart's works". Classical.net. Retrieved 27 October 2008.