Mpala

Mpala is the location of an early Catholic mission in the Belgian Congo. A military station was established at Mpala on the shores of Lake Tanganyika in May 1883. It was transferred to the White Fathers missionaries in 1885. At one time it was hoped that it would form the nucleus of a Christian kingdom in the heart of Africa. However, after a military expedition had to be sent to protect the mission from destruction by local warlords in 1892, civil control returned to the Belgian colonial authorities. The first seminary in the Congo was established at Mpala, and later the mission played an important role in providing practical education to the people of the region.

Mpala | |

|---|---|

Bishop’s Palace, Mission of Our Lady of M'Pala | |

Mpala | |

| Coordinates: 6.746314°S 29.531679°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Tanganyika |

| Territory | Moba |

| Founded by | Captain Émile Storms (Association Internationale Africaine) |

Location

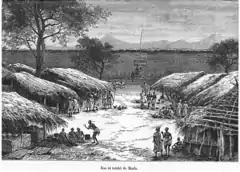

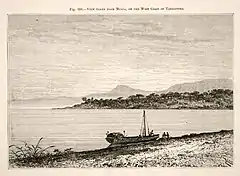

Mpala lies on the west shore of Lake Tanganyika in Tanganyika Province, to the north of Moba and south of Kalemie.[1] The station was established at the mouth of the Lufuku River.[2] The lake is about 400 miles (640 km) long and 45 miles (72 km) across. An 1898 book described it as an inland sea, navigated by a regular flotilla. At that time Albertville (now Kalemie), Mpala and Baudouinville (now Kirungu) were the main stations on the west shore of the lake.[3] Captain Storms, who founded Mpala, said the climate was healthy.[4] According to an 1886 in the Dublin Review,

... the fertility of the ground is such as to yield two crops of wheat or three of rice in a single year. Palm oil and india-rubber are to be had in abundance, the ivory furnished is said to be of the best quality, and the forests contain inexhaustible supplies of valuable timber. The stations were not only able to subsist on their own resources, but also to supply the wants of passing caravans...[5]

Foundation

In 1882 the International African Association had a military post at Karema on the east shore of Lake Tanganyika.[6] Captain Émile Storms took command of this post, then founded Mpala on the west shore of the lake, opposite Karema on the east shore, laying the foundations on 4 May 1883. He was assisted by the German explorer Paul Reichard.[7] He named the station after the friendly local chief Mpala, who on his deathbed told his people to obey the Europeans.[6] Storms gained authority during the two and a half years he spent at Mpala. The local chiefs came to rely on him for a monthly salary and for protection.[8]

On 30 November 1884 Reichart arrived at Mpala, coming from Katanga, and told him that his companion Richard Böhm had died in March.[8] A cable sent by Reichard from Mpala reported laconically "Böhm dead. Lake Upemba, Lufira [River], copper mines Katanga discovered".[9] Storms had his people build a great square stockade 30 metres (98 ft) on each side, using five thousand trees. The walls were made of mudbrick and were 60 centimetres (24 in) thick. The interior had seventeen rooms around a covered courtyard.[10] On 19 May 1885, Storms' great stockade was burned to the ground. Once the dried thatch had caught fire, little could be saved apart from the gunpowder.[11]

Storms found himself in a violent confrontation with Lusinga Iwa Ng'ombe, a powerful slaver whom the explorer Joseph Thomson called a "sanguinary potentate".[12] In the end, Lusinga was beheaded.[12] Another leader, Kansawara, who had submitted to Storms, decided to move into the vacancy left by Lusinga. He was defeated on 15 December 1884 and soon after submitted to Storms.[8]

At the Berlin Conference (1884-1885) the east side of the lake was assigned to the German sphere of influence.[6] King Leopold II of Belgium decided to focus his colonizing efforts on the lower Congo. He asked Mgr. Charles Lavigerie, the founder of the White Fathers missionary society, if he would like to replace the Belgian agents by missionaries at the two stations on Lake Tanganyika. Mgr. Lavigerie had a dream of founding a Christian kingdom in equatorial Africa to halt the tribal wars and to provide a base for the propagation of the faith. He wrote to Father Léonce Bridoux that this could be the moment to try to establish a Christian kingdom.[13]

When Storms heard that he was to be recalled, he was furious.[14] However, when two French priests, Isaac Moinet and Auguste Moncet, reached Mpala on 5 July 1885, Captain Storms handed over the fort, arms and ammunition, a sailboat and a garrison of askaris who had been paid for six months. The priests had five servants, of whom one was Christian.[13] The mission that had been founded at Mkapakwe on 12 September 1884 was transferred to the new mission, now called Mpala Notre Dame.[15] Moinet asked Storms what title he should take as successor to "His Majesty Emile the First, King of Tanganyika", and signed a letter he wrote to Storms "I, Moinet, Acting King of Mpala." However, the priests were committed to Lavigerie's dream of a Christian Kingdom, and saw the territory that Storms had acquired as the nucleus of the new state.[16]

Christian kingdom

The memory of the execution of Lusinga helped the priests, since the local chiefs did not want to suffer the same fate.[17] However, the fathers inherited a difficult situation. Various chiefs had submitted to Storms, giving him authority over a territory that extended 100 kilometres (62 mi) along the lake shore and 20 to 30 kilometres (12 to 19 mi) inland. This came with responsibility for defense and for resolving disputes. The fathers led a military expedition against a rebel leader in which villages were burned and slaves captured. This was not the role of a missionary.[13]

The French soldier Captain Léopold Louis Joubert offered his services to Lavigerie, and this was accepted in a letter of 20 February 1886. Joubert reached Zanzibar on 14 June 1886, and reached the mission at Karema on the east shore of the lake on 22 November 1886. He remained there for some months at the request of the Vicar Apostolic, Mgr. Jean-Baptiste-Frézal Charbonnier, to protect the mission against attacks by slavers. He crossed the lake and reached Mpala on 20 March 1887. Charbonnier had given him full authority as civil and military ruler of the Mpala region. He found that the priests had organized a police force of local warriors.[13]

Immediately after arriving, Joubert was thrown into the struggle with dealers in slaves and ivory. He engaged in skirmishes in March and again in August, where his small force of thirty soldiers armed with rifles came close to defeat. Joubert again had to intervene in November 1887, and in 1888 defeated a force of 80 slavers, but his forces were too small to prevent continued attacks. The constant fighting also worried some of the missionaries, notably Father François Coulbois, who were concerned that the slavers might decide to attack the mission itself.[13] Joubert married Agnes Atakaye on 13 February 1888.[18] She was the daughter of Kalembe, from Mpala. They were to have ten children, two of whom became priests.[19]

When Mgr. Charbonnier died on March 16, 1888, Coulbois became Pro-Vicar of Upper Congo. He did not recognize that Joubert had civil authority, and imposed tight restrictions on his actions. Both men appealed for support to Cardinal Lavigerie. In response, Lavigerie said that the missionaries must have no involvement with military affairs, and the military leader must live at a distance from the mission to avoid being identified with the mission. The new Vicar Apostolic, Bishop Bridoux, arrived in January 1889. He confirmed that Joubert was both civil and military leader, but said that military operations must be purely defensive. Joubert moved to St Louis de Murumbi, some distance away. In January 1889 the mission was cut off from the outside world by Abushiri Revolt against the Germans in Bagamoyo and Dar es Salaam. The mission suffered from repeated and deadly raids.[13] In 1890 the slavers Rajabu and Rumaliza launched a major attack on Mpala from the lake, but were beaten off. By 1891 the slavers had control of the entire western shore of the lake apart from Mpala and the Mrumbi plain.[19]

Return to security

A relief expedition was organized. It was led by Captain Alphonse Jacques and three other Europeans, and reached Zanzibar in June 1891, Karema on 16 October 1891 and Mpala on 30 October 1891. Captain Jacques gave Captain Joubert papers that made him a Belgian citizen and officer of the armed forces.[13] The expedition fought another pitched battle against the slavers. They founded the fortress of Albertville, and a few months later it was besieged by Rumaliza. The European press was critical of these actions, described as "military adventures of Cardinal Lavigerie".[19] Jacques left the volunteer Alexis Vrithoff to assist Joubert. Vrithoff died during an engagement on 5 April 1892. The danger from slavers was not finally removed until the 1893 expedition of Baron Francis Dhanis. The “kingdom” of Mpala was absorbed into the King Leopold’s Congo Free State.[13] Joubert lived on at St Louis de Murumbi until 1910, when it was abandoned due to sleeping sickness. He died at Moba on 27 May 1927.[13]

Later years

Although officially part of the Congo. the territory of Mpala retained considerable autonomy through the first half of the 1890s, administered by the missionaries.[16] The White Fathers erected a church and other buildings, and established gardens.[20]

A species of catfish locally called ndjagali use the Lufufo river for spawning from September to November.[21] The fish are considered a delicacy by the people of the region. In the past they were owned and caught communally, and traded with other communities for salt or iron. The people considered that the spirit of the earth, Kaomba, caused them to multiply.[22] The catfish were a major source of food for the villagers.[21] The missionaries recognized the beliefs about Kaomba and identified the sacred parts of the river. For many years they controlled access to the river, using it for their own food or to reward those loyal to them.[22]

A catechist training center was established in 1893.[23] On 26 August 1897 Father Auguste Huys arrived at Mpala, and after a few months was made director of the catechist school. He founded the first junior seminary in the Congo. After the summer holidays of 1898, with the authority of the Vicar-General Mgr. Victor Roelens, he brought all the most pious and best behaved pupils to Mpala and began to teach them the elements of Latin grammar. Soon after, Father Joseph Weghsteen created a Latin-Swahili grammar, which he printed on the press at Mpala. A history of the church and other works were also printed.[24] The junior seminary was officially inaugurated on 3 January 1899, with six candidates.[25]

In 1904 the first signs of sleeping sickness appeared, and for several years the disease raged among the population and the missionaries. Seven of the twenty one missionaries died. The missionaries built a sanctuary of the Blessed Virgin on one of the hills that overlooked the Mpala plain in the hope that she would provide protection against the epidemic. They also built lazarets where the White Sisters could provide assistance and comfort to the sick.[26] On 19 July 1905 all the pupils at Mpala left for the mission at Lusaka Saint-Jacques et Sainte Emilie, about 60 kilometres (37 mi) inland from the lake.[27]

With technological advances at the start of the twentieth century it became possible to fish the lake far from the shores, and fishing became an individual occupation, rather than communal as before.[22] In 1920 Father Tielemans, Superior of the Mpala mission, launched the Catholic Scouting movement in the Congo with a group of Sea Scouts.[28] Composer and politician Joseph Kiwele was born in Mpala in 1912. The mission developed commercial farming of wheat, potatoes and onions in the period between the two world wars. The missionaries taught the local people carpentry, masonry and boat making, all valuable skills. The majority of the mission-trained people found well paid work in commercial enterprises.[29] The old fortified buildings were still standing in 2005.[30] The buildings in the Mpala region today combine old and new forms. The materials and method of construction are traditional, but the rectangular structures draw from the traditional Western designs promoted by the missionaries.[31]

References

Citations

- Democratic Republic of the Congo (map).

- Royal Geographical Society 1884, p. 88.

- Boulger 1898, p. 85.

- Wiseman 1886, p. 413.

- Wiseman 1886, p. 413-414.

- Boulger 1898, p. 25.

- Coosemans 1947, p. 899-900.

- Coosemans 1947, p. 901.

- Fabian 2000, p. 148.

- Roberts 2012, p. 29.

- Roberts 2012, p. 43.

- Roberts 2012, p. 1.

- Casier 1987.

- Vail 1991, p. 196.

- Quatre Lettres Latins du Haut-Congo 1999, p. 365.

- Vail 1991, p. 197.

- Roberts 2012, p. 48.

- Il y a 80 ans ...

- Shorter 2003.

- Mudimbe 1994, p. 113.

- Bailey & Stewart 1984, p. 7.

- Roberts 1984, p. 49.

- Shorter 2003a.

- Quaghebeur & Kalengayi 2008, p. 19.

- Quaghebeur & Kalengayi 2008, p. 20.

- Quaghebeur & Kalengayi 2008, p. 25.

- Quaghebeur & Kalengayi 2008, p. 28.

- Tshimanga 2001, p. 117.

- Vail 1991, p. 200.

- Pirotte 2005, p. 93.

- Mudimbe 1994, p. 140.

Sources

- Bailey, Reeve M.; Stewart, Donald J. (6 September 1984). "Bagrid Catfishes from Lake Tanganyika, with a Key and Descriptions of New Taxa" (PDF). Ann Arbor: MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

- Boulger, Demetrius Charles (1898). The Congo State: Or, the Growth of Civilisation in Central Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-108-05069-2. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Casier, P. Jacques (1987). "Le royaume chrétien de Mpala : 1887 - 1893". Souvenirs Historiques. Nuntiuncula, Bruxelles (13). Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Coosemans, M. (4 December 1947). "STORMS (Emile Pierre Joseph)". Inst. Roy. Colon. Belge. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Democratic Republic of the Congo (map)" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Fabian, Johannes (2000). Out of Our Minds: Reasons and Madness in the Exploration of Central Africa. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92393-5. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- "Il y a 80 ans, le 27 Mai 1927, Mourait le Captiaine Joubert". Lavigerie. Archived from the original on 2013-06-17. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Mudimbe, V. Y. (1994). The idea of Africa. Indiana University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-253-20872-9. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Pirotte, Jean (2005). Les conditions matérielles de la mission: contraintes, dépassements et imaginaires, XVIIe-XXe siècles : Actes du colloque conjoint du CREDIC, de l'AFOM et du Centre Vincent Lebbe : Belley (Ain) du 31 août au 3 septembre 2004. KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 978-2-84586-682-9. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Quaghebeur, Marc; Kalengayi, Bibiane Tshibola (2008-01-01). Aspects de la culture à l'époque coloniale en Afrique centrale: Volume 8 : Presse ; Archives. L'Harmattan. p. 19. ISBN 978-2-296-05070-9. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- "Quatre Lettres Latins du Haut-Congo". Humanistica Lovaniensia. Leuven University Press. 1999. ISBN 978-90-6186-972-6. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Roberts, Allen F. (1984). "'Fishers of Men': religion and political economy among colonized Tabwa". Africa. 54 (2): 49–70. doi:10.2307/1159910. JSTOR 1159910. S2CID 145703116. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

- Roberts, Allen F. (2012-12-20). A Dance of Assassins: Performing Early Colonial Hegemony in the Congo. Indiana University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-253-00743-8. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Royal Geographical Society (1884). Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and monthly record of geography. Edward Stanford. p. 88. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Shorter, Aylward (2003). "Joubert, Leopold Louis". Dictionary of African Christian Biography. Archived from the original on 2013-05-24. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Shorter, Aylward (2003a). "Roelens, Victor". Dictionary of African Christian Biography. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Tshimanga, Charles (December 2001). JEUNESSE, FORMATION ET SOCIÉTÉ AU CONGO/KINSHASA 1890-1960. Editions L'Harmattan. p. 117. ISBN 978-2-296-40351-2. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Vail, LeRoy (1991). The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa. University of California Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-520-07420-0. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Wiseman, Nicholas Patrick (1886). "An African Eden". The Dublin Review. Burns and Oates. p. 413. Retrieved 2013-04-09.