Mudburra language

Mudburra, also spelt Mudbura, Mudbarra and other variants, and also known as Pinkangama, is an Aboriginal language of Australia.

| Mudbura | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Northern Territory, Australia |

| Region | Victoria River to Barkly Tablelands |

| Ethnicity | Mudbura, Kwarandji |

Native speakers | 92 (2016 census)[1] |

Pama–Nyungan

| |

| Mudbura Sign Language | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | dmw |

| Glottolog | mudb1240 |

| AIATSIS[1] | C25 |

| ELP | Mudburra |

McConvell suspects Karrangpurru was a dialect of Mudburra because people said it was similar. However, it is undocumented and thus formally unclassifiable.[1]

The language Mudburra is native to the western area of Barkly Region, southern area of Sturt Plateau and eastern area of Victoria River District, in Northern Territory Australia.[2] Furthermore, the areas in which the Mudbura people live are Yingawunarri (Top Springs), Marlinja (Newcastle Waters Station), Kulumindini (Elliott) and Stuart Highway.[2]

Information from the 2016 Australian census documented that there were 96 people speaking the Mudburra language, while other reports state that fewer than 10 people speak it fluently. It was also reported that children do not learn the traditional form of the language any more.[2]

Classification

The Mudbura language is classified under the family Pama- Nyungan and the subgroup Ngumpin- Yapa. Mudbura is subdivided as Eastern Mudbura dialect (also called Kuwaarrangu) and Western Mudbura dialect (also called Kuwirrinji) by native speakers.[2] This separation occurred due to the communication with speakers of other languages or dialects that happened over time. Proximately associated languages are Gurindji, Bilinarra, and Ngarinyman.[2]

History

During the pre- European era, the Mudbura people practised seasonal migration.[2] They resided around and south of the Murranji stock path, as well as the eastern side of Victoria River.[2] The Mudbura country was very arid and so the natives had to cover long distances to accommodate food search and other needs.[3] In the mid-1800s the Europeans arrived in the Barkley area and Victoria River and the first expedition of Victoria River occurred in 1855 by Augustus Charles Gregor's party.[4] In 1861 John McDouall Stuart and his party explored for the first time the Barkly Tablelands in search for a path from south to north.[5] Stuart named the water source “Newcastle Water” after his Grace the Duke of Newcastle, Secretary for the Colonies.[6] After examining it, it was apparent to him that this tributary was frequently occupied by the Mudbura people and neighboring communities as a water and food source.[6] In 1883, Newcastle Waters Station and Wave Hill Station were established and stocked with livestock.[5] As a result, the Mudbura people were being driven off their grounds from both sides.[2] The livestock farming that begun taking place in these areas resulted in significant changes on their environment and resources that had been a part of their lives for more than 10000 years ago.[2] Mudbura people moved to the stations in order to work as domestic or station workers to receive in return scarce quantities of food and to avoid violent encounters with Europeans.[2] The Stations, that were managed by Europeans, were not offering equal wages or satisfactory living conditions. In Newcastle Waters Station Mudbura was the major language spoken.[2]

Mudbura people created a type of shelter known as ‘nanji’ that was composed of ‘kurrunyu’ (bark) from ‘karnawuna’, lancewood (Acacia shirleyi).[2] Nanji would have a short door opening and inside the height from the ground to the ceiling was enough for an adult to stand upright.[2] Inside it offered enough space for up to 6 people and had ‘Liwiji’ (silky browntop grass) or ‘liyiji’ (desert red grass), handcrafted beds made by Mudbura people.[2]

Kriol was the language that resulted from a combination of Aboriginal languages and English that Aboriginal workers created in order to communicate with the Europeans in the 1900s.[7] Kriol started spreading to Mudbura community through the years and has since remained as language in their community.[7]

Present

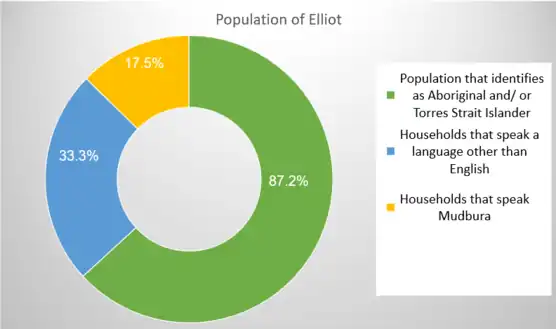

Nowadays, most Mudbura people reside in Elliott, a small area that is located between Darwin and Alice Springs, or in Marlinja. According to the 2016 census, 339 people live in Elliott.[8] The Mudbura language is currently at risk of obliteration as nowadays speakers of Mudbura communities either speak Aboriginal English or Kriol with the exception of a few elders that can still communicate it.[2]

Connection to similar dialects

Prior to the appearance of Europeans, Mudbura speakers were able to speak multiple Aboriginal languages that neighbored their land.[2] Such languages were Gurindji and Jingulu.[2] Speakers of Eastern Mudbura dialect, that live near Elliott and Marlinja have always been in close proximity to speakers of Jingulu and as a result some features of both communities have assimilated into each other.[2] Apart from that, a massive borrowing of words occurs between the two languages.[9] Speakers of the Western Mudbura dialect have been close to the Gurindji community and are characterized with a few shared features, that are different to Eastern Mudbura.[10]

Pensalfini[11] reported that: “The resulting mixing of Mudburra and Jingili people produced a cultural group who are referred to (by themselves in many cases, and by older Jingili) as ‘Kuwarrangu’, distinct from either Jingili or Mudburra”.

Phonology

Consonants

| Peripheral | Laminal | Apical | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labial | Velar | Palatal | Alveolar | Retroflex | |

| Stop | p~b | k~ɡ | c~ɟ | t~d | ʈ~ɖ |

| Nasal | m | ŋ | ɲ | n | ɳ |

| Lateral | ʎ | l | ɭ | ||

| Rhotic | ɾ | ||||

| Approximant | w | j | ɻ | ||

Alphabet

The alphabet of Mudbura language is written identically to the English language but it is spoken differently.[2] Mudbura language has 3 vowels: a, i and u. Letter a is pronounced like the vowel in “father”, in English.[2][12] Letter i sounds like the vowel in “bit” and u is pronounced like the vowel in “put”, in English.[2][12] Vowel combinations that produce different sounds are: “aw”, “ay”, “iyi”, “uwu”, “uwa”, “uwi”.[2] The consonats that are pronounced sometimes differently than in English are: b, d, k, j and the rest sound similarly to the English consonants.[2] Consonant combinations include: “rd”, “rn”, “rl”, “ng”, “ny”, “ly”, “rr”.[2] The sound “rd” is unique in the way that it resembles the sound of rolling the r combined with d.[2]

Grammar

Verbs

In Mudbura language there are verbs and coverbs.[2] Verbs have “inflection” endings depending on the role of a verb in a sentence.[2] The four inflections are: Imperative verbs, past tense verbs, present tense verbs and potential verbs.[2] There are 5 different conjugations that these inflecting verbs fall under, and each comes with different groups of endings.[2]

Example of Conjugation Group 1A:[2]

- Imperative: wanjarra (leave it!)

- Past: wanjana (left it)

- Present: wanjanini (leaves it)

- Potential: wanjarru (will leave it)

Example of Conjugation Group 1B:[2]

- Imperative: warnda (get it!)

- Past: warndana (got it)

- Present: warndanini (gets it)

- Potential: warndu (will get it)

Example of Conjugation Group 2A:[2]

- Imperative: yinba (sing it!)

- Past: yinbarna (sang it)

- Present: yinbarnini (sings it)

- Potential: yinba (will sing it)

Example of Conjugation Group 2B:[2]

- Imperative: janki (burn it!)

- Past: jankiyina (burnt it)

- Present: jankiyini (burns it)

- Potential: janki (will burn it)

Example of Conjugation Group 3:[13]

- Imperative: ngardangka (abandon it!)

- Past: ngardangana (abandoned it)

- Present: ngardanganini (abandons it)

- Potential: ngardangangku (will abandon it)

Example of Conjugation Group 4:[2]

- Imperative: nganja (eat it!)

- Past: ngarnana (ate it)

- Present: ngarnini (eats it)

- Potential: ngalu (will eat it)

Example of Conjugation group 5:[2]

- Imperative: yanda (go!)

- Past: yanana (went)

- Present: yanini (goes)

- Potential: yandu (will go)

Coverbs

In Mudbura, coverbs accompany inflecting verbs to indicate that the action is continuous.[2] Some of these have specific inflecting verbs with which they are exclusively combined.[2] Coverbs may be combined with different endings that change their meaning or their role in a sentence.[2]

Demonstratives

In Mudbura language definite and indefinite articles are not necessary before nouns, only demonstratives such as “nginya” and “yali” that mean this and that one close up, respectively.[2] The four demonstratives of Mudbura are used in any order in a sentence and they are: “nginya” (or “minya”), “yali” as stated before, “kadi” which means that one close up and “kuwala”, which means like this[2]. Demonstratives can have different endings that are similar to the Mudbura grammatical case endings[2]. The Mudbura cases are: nominative, ergative, dative, locative, allative and ablative.[2] Demonstratives can also take endings that indicate quantity like “-rra” for many and “-kujarra” for two[2].

Conjugation of "nginya":[2]

- Nominative: nginya, minya / this (one)

- Ergative: nginyali, minyali / this (one) did it

- Dative: nginyawu, minyawu / for this (one)

- Locative: nginyangka, minyangka / here

- Allative: nginyangkurra, mingyangkurra / to here

- Ablative: nginyangurlu, minyangurlu / from here

Conjugation of "kadi"[2]:

- Nominative: kadi/ that (one) close up

- Ergative: kadili / that (one) did it

- Dative: kadiwu / for that (one)

- Locative: kadingka / there

- Allative: kadingkurra / to there

- Ablative: kadingurlu / from there

Conjugation of "yali"[2]:

- Nominative: yali / that (one) long way away

- Ergative: yalili / that (one) did it

- Dative: yaliwu/ for that (one)

- Locative: yalingka/ there

- Allative: yalingkurra/ to there

- Ablative: yalingurlu/ from there

Pronouns

Mudbura pronouns are divided to three groups, the bound pronouns, the free pronouns and the indefinite pronouns.[2] Bound pronouns can be found free in a sentence or accompanying a noun or a free pronoun and usually they are combined at the end of the word “ba”.[2] They vary depending on the quantity of people and whether these are the subject or the object of the sentence, however there are no third person bound pronouns.[2] There are singular, dual and plural forms of bound pronouns.[2] Free pronouns are used to highlight a person and they also have possessive types that indicate ownership.[2] The three types of free pronouns are “ngayu” and “ngayi” which means I and me, “nyundu” which means you and “nyana” that means he/him/she/her.[2]

- Free pronouns:

- ngayu, ngayi / i, me

- nyundu / you

- nyana / he or him, she or her

The possessive forms of these are “ngayinya” which means my or mine, “nyununya” which means your or yours and “nyanunya” that means his, her or hers.[2]

- Possessive pronouns:

- ngayinya / my, mine

- nyununya / your, yours

- nyanunya / his, her, hers

When referring to many people the quantity endings that are stated in the Demonstratives section are added.[2] Indefinite pronouns are used to refer to unidentified objects or people.[2] They are: “nyamba” (something), “ngana” (someone), “nganali” (someone did it), “nyangurla” (sometime), “ngadjanga” (some amount), “wanjuwarra” (somewhere).[2]

Quantity endings

Quantity and numbers are indicated with endings that are added to words. Such are “-kujarra” for two, “-darra” or “-walija” for many.[2]

Sentences

The structure of sentences in Mudbura language does not follow specific rules, the subject can go in any order throughout a sentence and noun phrases may come apart if needed under the condition that all words of the phrase follow the same grammatical case.[2] Sentences can be intransitive meaning they do not include an object, transitive in which they include an object and a subject, semi-transitive in which they include a subject and an indirect object, and ditransitive in which they include a subject, an object and an indirect object.[2] Showing possession in a sentence can be expressed with bound or free pronouns in the case the speaker is referring to a part of their body, or with possessive pronouns in the case the speaker is referring to something they own.[2] Negative sentences are formed with the word “kula” combined with the verb in the associated tense.[2] This indicates that something is not, was not or will not and in terms of structure “kula” is found at the beginning of the sentence or right after the first word.[2] Other words and endings such as “-mulu” (don't), “wakurni” (no or nothing) and “-wangka” (without) can be used to express negativity.[2] Linking words or additional endings may be used in more complex sentences when these include more than 1 clause.[2] Examples are: “-baa” and “-maa” that mean when, if, which, who, “abala” that means when, that, while, which, then and “amba” that means so that, that, which, while.[2] The word and does not exist in the Mudbura language as words are either expressed consecutively without any linking words or some of the linking words stated above may be used.[2]

Vocabulary

Common question words[2]

- nyamba / what?

- nyambawu / why?

- ngana / who?

- nganawu / whose?

- wanji / which?

- wanjuwarra / where?

- ngadjanga / how much? or how many?’

- nyangurla / when?

- ngadarra / how?

Indicating direction[2]

- kankulu / up, above, on top of

- kanju / down, under, on the bottom, underneath, in

- kirrawarra / north

- kurlarra / south

- karlarra / west

- karrawarra / east

Numbers[2]

- nyangarlu / one

- kujarra / two

- murrkuna / three

- dardudardu / more, many, a whole lot

Note: Numbers 1, 2 and 3 are the only ones that have words in the Mudbura language.

Sign language

The Mudbura has (or had) a well-developed signed form of their language.[14] “Marnamarnda” is the name of the Mudbura sign language, which can be incorporated with speech or used by itself.[2] Mudburra people use it when hunting or to accommodate long-distance communication.[2]

References

- C25 Mudbura at the Australian Indigenous Languages Database, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- Meakins, Felicity (2021). Mudburra to English Dictionary. Chicago: Aboriginal Studies Press. ISBN 978-1-925302-59-2. OCLC 1255228353.

- Office of the Aboriginal Land Commissioner [Toohey, John]. (1980). Yingawunarri (Old Top Springs) Mudbura land claim: Report by the Aboriginal Land Commissioner, Mr. Justice Toohey, to the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs and to the Minister for Home Affairs. Canberra: Australian Government Public Service.

- Powell, Alan, 1936- (2015). Far Country: A Short History of the Northern Territory. UniprintNT, Charles Darwin University. ISBN 978-1-925167-10-8. OCLC 905215176.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - (Darrell), Lewis, D. (2011). The Murranji Track : ghost road of the drovers. Boolarong Press. ISBN 978-1-921920-23-3. OCLC 759165399.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Stuart, J.M. (1865). Fifth expedition, from November, 1860, to September, 1861. From the journals of John McDouall Stuart during the years 1858, 1859, 1860, 1861, & 1862. From https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/s/stuart/ john_mcdouall/journals/complete.html

- The Languages and Linguistics of Australia A Comprehensive Guide. Harold Koch, Rachel Nordlinger. Berlin/Boston. 2014. ISBN 978-3-11-039512-9. OCLC 890773949.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2018, 13 December). 2016 Census QuickStats: Elliott. From: http://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_ services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/UCL722014

- Black, Paul (1 April 2007). "Lexicostatistics with Massive Borrowing: The Case of Jingulu and Mudburra". Australian Journal of Linguistics. 27 (1): 63–71. doi:10.1080/07268600601172959. ISSN 0726-8602. S2CID 145770425.

- Meakins, Felicity; Pensalfini, Rob; Zipf, Caitlin; Hamilton-Hollaway, Amanda (2 July 2020). "Lend me your verbs: Verb borrowing between Jingulu and Mudburra". Australian Journal of Linguistics. 40 (3): 296–318. doi:10.1080/07268602.2020.1804830. ISSN 0726-8602. S2CID 225289078.

- Pensalfini, Robert (2001). On the Typological and Genetic Affiliation of Jingulu. Forty Years on: Ken Hale and Australian languages. Edited by Simpson, Jane, Nash, David, Laughren, Mary, Austin, Peter, and Alpher, Barry. Australian National University, Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.385-399.

- Nash, David; McConvell, Patrick; Capell, Arthur; Hale, Ken; Sutton, Peter; Rose, Deborah Bird; Wafer, Jim. Mudburra wordlist.

- Meakins, Felicity (2021). Mudburra to English Dictionary. Chicago: Aboriginal Studies Press. ISBN 978-1-925302-59-2. OCLC 1255228353.

- Kendon, A. (1988) Sign Languages of Aboriginal Australia: Cultural, Semiotic and Communicative Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press