Muhammad Akbar (Mughal prince)

Mirza Muhammad Akbar (Persian: میرزا محمد اکبر) (11 September 1657 – 31 March 1706)[1] was a Mughal prince and the fourth son of Emperor Aurangzeb and his chief consort Dilras Banu Begum. He went into exile in Safavid Persia after a failed rebellion against his father in the Deccan.

| Muhammad Akbar محمد اکبر | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shahzada of the Mughal Empire Sultan | |||||

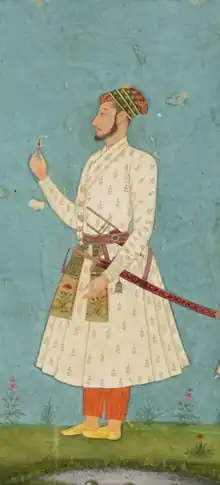

Prince holding a jewel, c. 1677 | |||||

| Born | 11 September 1657 Aurangabad, India | ||||

| Died | 31 March 1706 (aged 48) Mashad, Persia | ||||

| Burial | Mashad, Persia | ||||

| Spouse |

Salima Banu Begum

(m. 1672) | ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Babur | ||||

| Dynasty | |||||

| Father | Aurangzeb | ||||

| Mother | Dilras Banu Begum | ||||

He was the father of Neku Siyar, a pretender to the Mughal throne for a few months in 1719.[2]

Early life

Muhammad Akbar was born on 11 September 1657 in Aurangabad to Prince Muhiuddin (known as 'Aurangzeb' upon his accession) and his first wife and chief consort Dilras Banu Begum. His mother was a princess of the Safavid dynasty, and was the daughter of Mirza Badi-uz-Zaman Safavi, the viceroy of Gujarat. Dilras died when Muhammad Akbar was only one-month old.

Muhammad Akbar was brought up with special care and affection by his father and oldest sister, Princess Zeb-un-Nissa and described as his best-loved son in a letter to him, "God be my witness that I have loved you more than my other sons."[3]

Muhammad Akbar's siblings included his older sisters, Zeb-un-Nissa, Zinat-un-Nissa and Zubdat-un-Nissa and his older brother, Muhammad Azam Shah. Like other Mughal princes, Muhammad Akbar administered various provinces and fought minor campaigns under the guidance of experienced officers. His first independent command was during Aurangzeb's war of the Jodhpur succession.

Marriages

On 18 June 1672,[4] Muhammad Akbar was wedded to Princess Salima Banu Begum, the eldest daughter of Prince Sulaiman Shikoh, and a granddaughter of Dara Shikoh.[5]

Later, Muhammad Akbar also married a daughter of an Assamese nobleman. He was the father of two sons and two daughters, including Neku Siyar, who briefly became Mughal emperor in 1719.

Rajput rebellion

Maharaja Jaswant Singh, of Marwar, was also a high-ranking Mughal officer died at his post on the Khyber Pass on 10 December 1678 without leaving a male issue; two of his wives were pregnant at the time of his death, leaving his succession unclear. On learning of his death, Aurangzeb, immediately dispatched a large army on 9 January 1679 to occupy Jodhpur. One of the divisions of this army was commanded by Muhammad Akbar.

The occupation of Jodhpur was ostensibly to secure the succession for any male infant born to Jaswant's pregnant widows. Aurangzeb declared that such rightful heir would be invested with his patrimony upon coming of age. However, relations between Jaswant Singh and Aurangzeb had not been good, and it was feared that Aurangzeb would annex the state on this pretext. Indeed, incumbent Marwari officers were replaced by Mughals. After effectively annexing the largest Hindu state in northern India, Aurangzeb reimposed the jaziya tax on its non-Muslim population on 2 April 1679, almost a century after it had been abolished by emperor Akbar.

One of Jaswant's pregnant wives, Rani Jadav Jaskumvar, delivered a son, Ajit Singh. Officers loyal to Jaswant Singh brought his family back to Jodhpur and rallied the clan to the standards of the infant. The Rathore Rajputs of Jodhpur forged an alliance with the neighboring Sisodia Rajputs of Mewar. Raj Singh I withdrew his army to the western portion of his kingdom, marked by the rugged Aravalli Hills and secured by numerous hill-forts, triggering the Rajput rebellion. From their positions, the smaller but faster Rajput cavalry units could surprise the Mughal outposts in the plains, loot their supply trains, and bypass their camps to ravage neighbouring Mughal provinces.

In the second half of 1680, after several months of such setbacks, Aurangzeb decided on an all-out offensive. Niccolao Manucci, an Italian gunner in the Mughal army, says: "for this campaign, Aurangzeb put in pledge the whole of his kingdom." Three separate armies, under Aurangzeb's sons Muhammad Akbar, Azam Shah and Mirza Muhammad Mu'azzam, penetrated the Aravallis from different directions. However, their artillery lost its effectiveness while being dragged around the rugged hills and both Azam Shah and Mirza Muhammad Muaazzam were defeated by the Rajputs and retreated.[6]

Rebellion against Aurangzeb

Muhammad Akbar and his general Tahawwur Khan had been instructed to try to bribe the Rajput nobles to the Mughal side, but in these attempts, they themselves were ensnared by the Rajputs. The Rajputs incited Muhammad Akbar to rebel against his father and offered all support. They pointed out to him that Aurangzeb's attempt to annex the Rajput states was disturbing the stability of the sub-continent. They also reminded him that the open bigotry displayed by Aurangzeb in reimposing jaziya and demolishing temples was contrary to the wise policies of his ancestors. According to Bhimsen, he is also supposed to have written to his father:

On the Hindu community [firqa] two calamities have descended, the exaction of Jizya in the towns and the oppression of the enemy in the countryside.[7]

Muhammad Akbar lent a willing ear to the Rajputs and promised to restore the policies Akbar. On 1 January 1681, he declared himself emperor, issued a manifesto deposing his father, and marched towards Ajmer to fight him.

As the commander of a Mughal division, Akbar had a force of 12,000 cavalry with supporting infantry and artillery. Maharana Amar Singh II of Mewar added 6,000 Rajput cavalry, half his own army. As this combined army crossed Marwar, numerous war-bands of Rathores joined up and increased its strength to 25,000 cavalry. Meanwhile, various Mughal divisions deployed around the Aravallis had been racing to come to Aurangzeb's aid. Aurangzeb however resorted to threats and treachery: he sent a letter to Tahawwur Khan promising to pardon him but also threatening to have his family publicly dishonored by camp ruffians if he refused to submit. Tahawwur Khan secretly came over to meet Aurangzeb but was killed in a scuffle at the entrance to Aurangzeb's tent.

Aurangzeb then wrote a false letter to Muhammad Akbar and arranged it such that the letter was intercepted by the Rajputs.[8] In this letter, Aurangzeb congratulated his son for finally bringing the Rajput guerillas out in the open where they could be crushed by father and son together. The Rajput commanders suspected this letter to be false but took it to Muhammad Akbar's camp for an explanation. Here they discovered that Tahawwur Khan had disappeared. Suspecting the worst, the Rajputs departed in the middle of the night. The next morning, Akbar woke to find his chief adviser and his allies gone and his own soldiers deserting by the hour to Aurangzeb. Muhammad Akbar avoided the near-certain prospect of war and defeat to his father by hastily departing the camp with a few close followers. He caught up with the Rajput commanders and mutual explanations followed.

Exile with Marathas and in Persia

Seeing that Muhammad Akbar had attempted no treachery and that he could be useful, the Rathore leader Durgadas Rathore took Akbar to the court of the Maratha Chhatrapati Sambhaji, seeking support for the project of placing him on the throne of Delhi. Muhammad Akbar stayed with Sambhaji for five years, hoping to be lent men and money to seize the Mughal throne. Sambhaji was occupied by wars against the Siddis of Janjira; Chikka Devaraja of Mysore; the Portuguese in Goa; and Aurangzeb himself.

In September 1686, Sambhaji sent Muhammad Akbar into exile in Persia. Muhammad Akbar was said to pray daily for the early death of his father, hoping that would give him another chance to seize the Mughal throne for himself. On hearing of this, Aurangzeb is said to have remarked, "Let us see who dies first. He or I!" Muhammad Akbar died in 1706, one year before his father, in the town of Mashhad.

Two of Muhammad Akbar's children, brought up by the Rajputs, were handed over to Aurganzeb as a result of peace negotiations. Muhammad Akbar's daughter Safiyat-un-nissa was sent to her grandfather in 1696 and his son Buland Akhtar was returned in 1698. The latter, when presented in court, shocked the emperor and nobles by speaking fluently in the Rajasthani language.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Muhammad Akbar (Mughal prince) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Legacy

In the words of Sir Jadunath Sarkar:

The rebellion of Prince Akbar, though it was fostered by the Rajputs and originated, grew to fullness, and expired in Northern India, changed the history of the Deccan and hastened the fate of the Mughal Empire as well. His flight to Shambhuji raised a danger to the throne of Delhi which could be met only by Aurangzib's personal appearance in the south.

But for this alliance, the Emperor would have left Bijapur and Golconda to be occasionally threatened and fleeced by his generals, while the Maratha king would have been tolerated as a necessary evil and even as a thorn in the side of Bijapur.

But Akbar's flight to the Deccan forced a complete change on the imperial policy in that quarter. The first task of Aurangzeb now was to crush the power of Shambhuji and render Akbar impotent for mischief. For this he patched up a peace with the Maharana (June 1681) and left for the Deccan to direct the operations of his army.

Notes

- According to Tarikh-i-Muhammadi, his date of death is 31 March 1706 (Irvine, William (1922) Later Mughals, Volume I, Jadunath Sarkar ed., Calcutta: M. C. Sarkar & Sons, p.1)

- Elliot, Sir Henry Miers (1959). Later Moghuls. Susil Gupta (India) Private. p. 97.

- Sir Jadunath Sarkar (1919). Studies in Mughal India. W. Heffer and Sons. p. 91.

- Sarker, Kobita (2007). Shah Jahan and his paradise on earth : the story of Shah Jahan's creations in Agra and Shahjahanabad in the golden days of the Mughals (1. publ. ed.). Kolkata: K.P. Bagchi & Co. p. 142. ISBN 9788170743002.

- Hansen, Waldemar (1972). The peacock throne : the drama of Mogul India (1. Indian ed., repr. ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 394. ISBN 812080225X.

- Storia do Mogor By Niccolao Manucci

- Kruijtzer, Gjis, ed. (2009), "Muhammmad Akbar", Xenophobia in the Seventeenth-century India, Leiden University press, p. 200, ISBN 978-9087280680

- Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. p. 190. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

References

- Jadunath Sarkar, History of Aurangzeb, Vols. 3&4

- Manucci, Storia do Mogor.