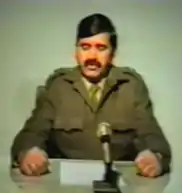

Mohammad Aslam Watanjar

Mohammad Aslam Watanjar (Pashto: محمداسلم وطنجار, 1946 – November 2000) was an Afghan Army general and politician. He played a significant role in the coup in 1978 that killed the Afghan president Mohammad Daud Khan and started the "Saur Revolution". Watanjar later became a member of the politburo in the Soviet-backed Democratic Republic of Afghanistan.

General Aslam Watanjar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Defence | |

| In office 6 March 1990 – April 1992 | |

| Preceded by | Shahnawaz Tanai |

| Succeeded by | Ahmad Shah Massoud |

| In office April – 28 July 1979 | |

| Preceded by | Abdul Qadir |

| Succeeded by | Hafizullah Amin |

| Minister of Internal Affairs | |

| In office 15 November 1988[1] – 6 March 1990 | |

| Preceded by | Sayed Mohammad Gulabzoy |

| Succeeded by | Raz Muhammad Paktin |

| In office 28 July 1979[2] – 19 September 1979 | |

| Preceded by | Sherjan Mazdoryar |

| Succeeded by | Vacant |

| In office 11 July 1978[3] – 1 April 1979 | |

| Preceded by | Nur Ahmad Nur |

| Succeeded by | Sherjan Mazoryar |

| Minister of Communications | |

| In office 10 January 1980 – 1988 | |

| Preceded by | Mohammad Zarif |

| Succeeded by | Unknown |

| In office 30 April 1978 – July 1978 | |

| Preceded by | Abdul Karim Attayee |

| Succeeded by | Sayed Mohammad Gulabzoy |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1946 Paktia Province, Kingdom of Afghanistan |

| Died | 24 November 2000 (aged 53–54) Odesa, Ukraine |

| Political party | PDPA-Khalq |

| Children | 8 (Including Illa Watanjar)[4] |

| Profession | Politician Military officer |

| Awards | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1967–1992 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | 1973 Afghan coup d'état[5] Saur Revolution 1979 uprisings in Afghanistan Tajbeg Palace assault (alleged)[6] Soviet-Afghan War Afghan Civil War (1989-1992) 1990 Afghan coup d'état attempt Afghan Civil War (1992-1996) (until 1992)[4] |

Early life

An Andar Ghilzai Pashtun from Zurmula in Paktia, Aslam Watanjar trained as a tank officer in the Soviet Union following his graduation from the Military Academy in Kabul in 1967. As a young tanker, He took part in the Coup of 1973 helping Daoud Khan into power but was later removed from his position.[7]

The Saur Revolution

Watanjar's role in the communist coup of 1978 was important. Instructed by Hafizullah Amin, he initiated the march of tank forces from the motorized forces of numbers 4 and 15 near Pul-e-Charkhi (seemingly 4th and 15th Armoured Brigades, see 201 Khalid Ibn Walid Corps) against the government.

Colonel Aslam Watanjar was the Army commander on the ground during the Coup, and his troops gained control of Kabul. Colonel Abdul Qadir, the leader of the Air Force squadrons, also launched a major attack on the Royal Palace, in the course of which Mohammed Daoud Khan was killed. Watanjar was present when corpses of the president and his family were buried in a pit.[8]

Colonel Watanjar was also in charge of the announcement over Radio Kabul, in the Pashto language, that a Revolutionary Council of the Armed Forces had been established, with Colonel Abdul Qadir at its head. The council's initial statement of principles, issued late in the evening of April 27, was a noncommittal affirmation of Islamic, democratic, and non-aligned ideals.

He was in charge of the operation until Amin took over from him in the evening. On April 30 the RC issued the first of a series of fateful decrees. The decree formally abolished the military's revolutionary council.

Part of the Khalqi Government

Following the coup, Watanjar was appointed deputy prime minister and minister of communications. Later he served successively as minister of the interior, of defense, and again of the interior until he joined others in a plot against Amin.

The Herat uprising also set off a new round in the Afghan regime's internal power struggle. To assuage charges of weak performance in the military leadership, Taraki finally granted Watanjar the position of Minister of Defense.

Watanjar's move to take over the Defense Ministry was a demonstrable exploitation of Amin's vulnerability in the aftermath of the failings of the army. However Watanjar's criticism of Amin's mass repression[9] led to Amin taking over the defense portfolio on July 1979, replacing Watanjar on the grounds that he was a Taraki-sympathizer.

Aslam Watanjar joined forces with Sarwari, Gulabzoy and others Khalqis in a plot against then Prime Minister Hafizullah Amin.

Except for Sarwari, who was from the province of Ghazni, the others were from Paktia. They had influence with the army, which was officered by a considerable number of persons from Paktia.

Until their break with Amin, Sarwari was head of the Intelligence Department (AGSA), while the others were cabinet ministers. At first close friends of Amin, they later turned against him, siding with President Nur Mohammad Taraki in opposition to Amin.

When Amin overcame them, they took refuge in the Soviet embassy along with Sarwari and Gulabzoy.

Part of the Parchamite Government

The presence in Soviet Army, Sarwari, Watanjar, and Gulabzoy might have influenced the officers of the Afghan Armed Forces to not to respond the invasion. Along with them, he served as a guide for the Soviets.

After the invasion he was promoted to membership in the central committee and the Revolutionary Council and was appointed Minister of Communications. In June 1981 he was added to the Politburo.

Later he served successively as Minister of Defense and again of the Interior.

He also headed the official Afghan delegation to Baikonur, in his position of communications minister and member of its ruling Politburo.

On March 6, 1990, General Watanjar intercepted a tank battalion of Shahnawaz Tanai during Tanai's coup attempt, which eventually failed. Watanjar was awarded a four-star rank by President Najibullah and he also became Secretary of Defense.[10]

After the fall of Kabul and the collapse of President Najibullah's government, he left the country.

Later life and death

On 24 November 2000, Watanjar died of cancer while in exile, in the Ukrainian city of Odesa. He was 56.[11]

About Watanjar's later years of life, Soviet General Makhmut Gareev said:

He lived in Moscow with a large family, having, like most Afghan emigrants, no apartment, no residence permit, no means of subsistence. In the end, he was thrown out of the apartment he temporarily occupied, and he was forced to move to Odessa. None of the leaders of the Russian Ministry of Defense of that Yeltsin era wanted to meet with the Afghan military leader, with whom we solved our common tasks in Afghanistan.[12]

Speaking about the personality of Mohammad Watanjar, Gareev notes:

The main drawback of Watanjar was that his soulfulness, overly gentle nature and kindness prevented him from fully exercising power, practically organizing and demanding the fulfillment of assigned tasks. In the conditions of low organization and disorder that existed then in Afghanistan, these flaws in the nature and methods of Watanjar's work weakened the control of subordinate departments and troops. But in general, General Watanjar served his people and the Republic of Afghanistan honestly and faithfully.[12]

References

- Bradsher, Harry (1999). Afghan Communism and Soviet Intervention. Oxford University Press. pp. 313, 342. ISBN 0195790170.

- Male, Beverly (1982). Revolutionary Afghanistan: A Reappraisal. Croom Helm. p. 155. ISBN 0709917163.

- Male, Beverly (1982). Revolutionary Afghanistan: A Reappraisal. Croom Helm. p. 111. ISBN 0709917163.

- "ВАТАНДЖАР Мохаммад Аслам" (in Russian). База персоналий "Кто есть кто в Центральной Азии". Archived from the original on 2016-09-23. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- "ArtOfWar. Каменев Александр Иванович. Закат Апрельской революции (записки военного переводчика)". artofwar.ru. Retrieved 2023-07-08.

- Braithwaite 2011.

- "Напрасно ли сражались герои Афганской революции?". 2007-11-16. Archived from the original on 2007-11-16. Retrieved 2023-07-08.

- "An Afghan Secret Revealed Brings End of an Era". The New York Times. 1 February 2009.

- "Напрасно ли сражались герои Афганской революции?". 2007-11-16. Archived from the original on 2007-11-16. Retrieved 2023-07-08.

- Burns, John F. (10 May 1990). "Kabul Journal; in Power Still, Afghan Can Thank His 4-Star Aide". The New York Times.

- "In memoriam / Заметки на погонах / Независимая газета". nvo.ng.ru. Retrieved 2023-07-08.

- "Напрасно ли сражались герои Афганской революции?". 2007-11-16. Archived from the original on 2007-11-16. Retrieved 2023-07-08.