Submarine hull

A submarine hull has two major components, the light hull and the pressure hull. The light hull (casing in British usage) of a submarine is the outer non-watertight hull which provides a hydrodynamically efficient shape. The pressure hull is the inner hull of a submarine that maintains structural integrity with the difference between outside and inside pressure at depth.

Shapes

Modern submarines are usually cigar-shaped. This design, already visible on very early submarines, is called a "teardrop hull". It is structurally efficient for withstanding external pressure, and significantly reduces the hydrodynamic drag on the sub when submerged, but decreases the sea-keeping capabilities and increases drag while surfaced.

History

The concept of an outer hydrodynamically streamlined light hull separated from the inner pressure hull was first introduced in the early pioneering submarine Ictineo I designed by the Spanish inventor Narcís Monturiol in 1859.[1][2] However, when military submarines entered service in the early 1900s, the limitations of their propulsion systems forced them to operate on the surface most of the time; their hull designs were a compromise, with the outer hulls resembling a ship, allowing for good surface navigation, and a relatively streamlined superstructure to minimize drag under water. Because of the low submerged speeds of these submarines, usually well below 10 knots (19 km/h), the increased drag for underwater travel by the conventional ship-like outer hull was considered acceptable. Only late in World War II, when technology enhancements allowed faster and longer submerged operations and increased surveillance by enemy aircraft forced submarines to spend most of their times below the surface, did hull designs become teardrop shaped again, to reduce drag and noise. USS Albacore (AGSS-569) was a unique research submarine that pioneered the American version of the teardrop hull form (sometimes referred to as an "Albacore hull") of modern submarines. On modern military submarines the outer hull (and sometimes also the propeller) is covered with a thick layer of special sound-absorbing rubber, or anechoic plating, to make the submarine more difficult to detect by active and passive sonar.

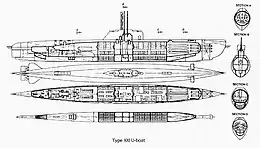

Types

All small modern submarines and submersibles, as well as the oldest ones, have a single hull. However, for large submarines, the approaches have separated. All Soviet heavy submarines are built with a double hull structure, but American submarines usually are single-hulled. They still have light hull sections in bow and stern, which house main ballast tanks and provide hydrodynamically optimized shape, but the main, usually cylindrical, hull section has only a single plating layer.

Light hull

The double hull of a submarine is different from a ship's double hull. The external hull, which actually forms the shape of submarine, is called the outer hull, casing or light hull. It defines the hydrodynamic performance of submarine, which affects the amount of power required to drive the vessel through the water. This term is especially appropriate for Russian submarine construction, where the light hull is usually made of thin steel plate, as it has the same pressure on both sides. The light hull can be used to mount equipment, which if attached directly to the pressure hull could cause unnecessary stress. The double hull approach also saves space inside the pressure hull, as the ring stiffeners and longitudinals can be located between the hulls. These measures help minimise the size of the pressure hull, which is much heavier than the light hull. Also, in case the submarine is damaged, the light hull takes some of the damage and does not compromise the vessel's integrity, as long as the pressure hull is intact.

Pressure hull

Inside the outer hull there is a strong hull, or pressure hull, which withstands the outside pressure and has normal atmospheric pressure inside. The pressure hull is generally constructed of thick high-strength steel with a complex stiffening structure and high strength reserve, and is divided by watertight bulkheads into several compartments. The pressure and light hulls are separated by a gap in which numerous steel structural elements connect the light hull and pressure hull and form a three-dimensional structure which provides increased strength and buckling stability. The interhull space is used for some of the equipment which can tolerate the high external pressure at maximum depth and exposure to the water. This equipment significantly differs between submarines, and generally includes various water and air tanks. In a single-hull submarine, the light hull is discontinuous and exists mainly at the bow and stern.

Pressure hulls have a circular cross section as any other shape would be substantially weaker. The construction of a pressure hull requires a high degree of precision. This is true irrespective of its size. Even a one-inch (25 mm) deviation from cross-sectional roundness results in over 30 percent decrease of hydrostatic load capacity.[3] Minor deviations are resisted by the stiffener rings, and the total pressure force of several million longitudinally-oriented tons must be distributed evenly over the hull by using a hull with a circular cross section. This design is the most resistant to compressive stress and without it no material could resist water pressure at submarine depths. A submarine hull requires expensive transverse framing construction, with ring frames closely spaced to stiffen against buckling instability. No hull parts may contain defects, and all welded joints are checked several times using different methods.

Typhoon-class submarines feature multiple pressure hulls that simplify internal design while making the vessel much wider than a normal submarine. In the main body of the sub, two long pressure hulls lie parallel side by side, with a third, shorter pressure hull above and partially between them (which protrudes just below the sail), and two other centreline pressure hulls, for torpedoes at the bow, and steering gear at the stern. This also greatly increases their survivability – even if one pressure hull is breached, the crew members in the others are relatively safe if the submarine can be prevented from sinking, and there is less potential for flooding.

Dive depth

The dive depth cannot be increased easily. Simply making the hull thicker increases the weight and requires reduction of the weight of onboard equipment, ultimately resulting in a bathyscaphe. This is affordable for civilian research submersibles, but not military submarines, so their dive depth was always bounded by current technology.

World War One submarines had their hulls built of carbon steel, and usually had test depths of no more than 100 metres (330 ft). During World War Two, high-strength alloyed steel was introduced, allowing for depths up to 200 metres (660 ft); post-war calculations have suggested crush depths exceeding 300 metres (980 ft) for late-war German Type VII U-boats. High-strength alloyed steel is still the main material for submarines today, with 250 to 350 metres (820 to 1,150 ft) depth limit, which cannot be exceeded on a military submarine without sacrificing other characteristics. To exceed that limit, a few submarines were built with titanium hulls. Titanium has a better strength to weight ratio and durability than most steels, and is non-magnetic. Titanium submarines were especially favoured by the Soviets, as they had developed specialized high-strength alloys, built an industry for producing titanium with affordable costs, and have several types of titanium submarines. Titanium alloys allow a major increase in depth, but other systems need to be redesigned as well, so test depth was limited to 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) for the Soviet submarine Komsomolets, the deepest-diving military submarine. Despite its benefits, the high costs of titanium submarine construction led to its abandonment as the Cold War ended.

Other types

There are examples of more than two hulls inside a submarine. The light hull of Typhoon-class submarines houses two main pressure hulls, a smaller third pressure hull constituting most of the sail, two other for torpedoes and steering gear, and between the main hulls 20 MIRV SLBMs along with ballast tanks and some other systems. The Royal Netherlands Navy Dolfijn- and Potvis-class submarines housed three main pressure hulls. The Russian submarine Losharik is able to dive over 2000 m with its multi-spherical hull.

See also

References

- Tom Chaffin (2010). The H. L. Hunley: The Secret Hope of the Confederacy. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-1-4299-9035-6.

- Matthew Stewart (2003). Monturiol's Dream: The Extraordinary Story of the Submarine Inventor who Wanted to Save the World. Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-41439-8.

- US Naval Academy