Programming paradigm

Programming paradigms are a way to classify programming languages based on their features. Languages can be classified into multiple paradigms.

Some paradigms are concerned mainly with implications for the execution model of the language, such as allowing side effects, or whether the sequence of operations is defined by the execution model. Other paradigms are concerned mainly with the way that code is organized, such as grouping a code into units along with the state that is modified by the code. Yet others are concerned mainly with the style of syntax and grammar.

Some common programming paradigms are,[1][2][3]

- Imperative in which the programmer instructs the machine how to change its state,

- procedural which groups instructions into procedures,

- object-oriented which groups instructions with the part of the state they operate on,

- Declarative in which the programmer merely declares properties of the desired result, but not how to compute it

- functional in which the desired result is declared as the value of a series of function applications,

- logic in which the desired result is declared as the answer to a question about a system of facts and rules,

- reactive in which the desired result is declared with data streams and the propagation of change

Symbolic techniques such as reflection, which allow the program to refer to itself, might also be considered as a programming paradigm. However, this is compatible with the major paradigms and thus is not a real paradigm in its own right.

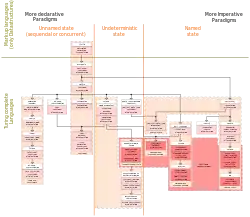

For example, languages that fall into the imperative paradigm have two main features: they state the order in which operations occur, with constructs that explicitly control that order, and they allow side effects, in which state can be modified at one point in time, within one unit of code, and then later read at a different point in time inside a different unit of code. The communication between the units of code is not explicit. Meanwhile, in object-oriented programming, code is organized into objects that contain a state that is only modified by the code that is part of the object. Most object-oriented languages are also imperative languages. In contrast, languages that fit the declarative paradigm do not state the order in which to execute operations. Instead, they supply a number of available operations in the system, along with the conditions under which each is allowed to execute.[4] The implementation of the language's execution model tracks which operations are free to execute and chooses the order independently. More at Comparison of multi-paradigm programming languages.

Overview

Just as software engineering (as a process) is defined by differing methodologies, so the programming languages (as models of computation) are defined by differing paradigms. Some languages are designed to support one paradigm (Smalltalk supports object-oriented programming, Haskell supports functional programming), while other programming languages support multiple paradigms (such as Object Pascal, C++, Java, JavaScript, C#, Scala, Visual Basic, Common Lisp, Scheme, Perl, PHP, Python, Ruby, Oz, and F#). For example, programs written in C++, Object Pascal or PHP can be purely procedural, purely object-oriented, or can contain elements of both or other paradigms. Software designers and programmers decide how to use those paradigm elements.

In object-oriented programming, programs are treated as a set of interacting objects. In functional programming, programs are treated as a sequence of stateless function evaluations. When programming computers or systems with many processors, in process-oriented programming, programs are treated as sets of concurrent processes that act on a logical shared data structures.

Many programming paradigms are as well known for the techniques they forbid as for those they enable. For instance, pure functional programming disallows use of side-effects, while structured programming disallows use of the goto statement. Partly for this reason, new paradigms are often regarded as doctrinaire or overly rigid by those accustomed to earlier styles.[7] Yet, avoiding certain techniques can make it easier to understand program behavior, and to prove theorems about program correctness.

Programming paradigms can also be compared with programming models, which allows invoking an execution model by using only an API. Programming models can also be classified into paradigms based on features of the execution model.

For parallel computing, using a programming model instead of a language is common. The reason is that details of the parallel hardware leak into the abstractions used to program the hardware. This causes the programmer to have to map patterns in the algorithm onto patterns in the execution model (which have been inserted due to leakage of hardware into the abstraction). As a consequence, no one parallel programming language maps well to all computation problems. Thus, it is more convenient to use a base sequential language and insert API calls to parallel execution models via a programming model. Such parallel programming models can be classified according to abstractions that reflect the hardware, such as shared memory, distributed memory with message passing, notions of place visible in the code, and so forth. These can be considered flavors of programming paradigm that apply to only parallel languages and programming models.

Criticism

Some programming language researchers criticise the notion of paradigms as a classification of programming languages, e.g. Harper,[8] and Krishnamurthi.[9] They argue that many programming languages cannot be strictly classified into one paradigm, but rather include features from several paradigms. See Comparison of multi-paradigm programming languages.

History

Different approaches to programming have developed over time, being identified as such either at the time or retrospectively. An early approach consciously identified as such is structured programming, advocated since the mid 1960s. The concept of a "programming paradigm" as such dates at least to 1978, in the Turing Award lecture of Robert W. Floyd, entitled The Paradigms of Programming, which cites the notion of paradigm as used by Thomas Kuhn in his The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962).[10] Early programming languages did not have clearly defined programming paradigms and sometimes programs made extensive use of goto statements, liberal use of these statements lead to "spaghetti code" which is difficult to work with. This led to the development of structured programming paradigms that disallowed the use of goto statements and only allow the use of clearly defined programming constructs.[11]

Machine code

The lowest-level programming paradigms are machine code, which directly represents the instructions (the contents of program memory) as a sequence of numbers, and assembly language where the machine instructions are represented by mnemonics and memory addresses can be given symbolic labels. These are sometimes called first- and second-generation languages.

In the 1960s, assembly languages were developed to support library COPY and quite sophisticated conditional macro generation and preprocessing abilities, CALL to (subroutines), external variables and common sections (globals), enabling significant code re-use and isolation from hardware specifics via the use of logical operators such as READ/WRITE/GET/PUT. Assembly was, and still is, used for time-critical systems and often in embedded systems as it gives the most direct control of what the machine does.

Procedural languages

The next advance was the development of procedural languages. These third-generation languages (the first described as high-level languages) use vocabulary related to the problem being solved. For example,

- COmmon Business Oriented Language (COBOL) – uses terms like file, move and copy.

- FORmula TRANslation (FORTRAN) – using mathematical language terminology, it was developed mainly for scientific and engineering problems.

- ALGOrithmic Language (ALGOL) – focused on being an appropriate language to define algorithms, while using mathematical language terminology, targeting scientific and engineering problems, just like FORTRAN.

- Programming Language One (PL/I) – a hybrid commercial-scientific general purpose language supporting pointers.

- Beginners All purpose Symbolic Instruction Code (BASIC) – it was developed to enable more people to write programs.

- C – a general-purpose programming language, initially developed by Dennis Ritchie between 1969 and 1973 at AT&T Bell Labs.

All these languages follow the procedural paradigm. That is, they describe, step by step, exactly the procedure that should, according to the particular programmer at least, be followed to solve a specific problem. The efficacy and efficiency of any such solution are both therefore entirely subjective and highly dependent on that programmer's experience, inventiveness, and ability.

Object-oriented programming

Following the widespread use of procedural languages, object-oriented programming (OOP) languages were created, such as Simula, Smalltalk, C++, Eiffel, Python, PHP, Java, and C#. In these languages, data and methods to manipulate it are kept as one unit called an object. With perfect encapsulation, one of the distinguishing features of OOP, the only way that another object or user would be able to access the data is via the object's methods. Thus, an object's inner workings may be changed without affecting any code that uses the object. There is still some controversy raised by Alexander Stepanov, Richard Stallman[12] and other programmers, concerning the efficacy of the OOP paradigm versus the procedural paradigm. The need for every object to have associative methods leads some skeptics to associate OOP with software bloat; an attempt to resolve this dilemma came through polymorphism.

Because object-oriented programming is considered a paradigm, not a language, it is possible to create even an object-oriented assembler language. High Level Assembly (HLA) is an example of this that fully supports advanced data types and object-oriented assembly language programming – despite its early origins. Thus, differing programming paradigms can be seen rather like motivational memes of their advocates, rather than necessarily representing progress from one level to the next. Precise comparisons of competing paradigms' efficacy are frequently made more difficult because of new and differing terminology applied to similar entities and processes together with numerous implementation distinctions across languages.

Further paradigms

Literate programming, as a form of imperative programming, structures programs as a human-centered web, as in a hypertext essay: documentation is integral to the program, and the program is structured following the logic of prose exposition, rather than compiler convenience.

Independent of the imperative branch, declarative programming paradigms were developed. In these languages, the computer is told what the problem is, not how to solve the problem – the program is structured as a set of properties to find in the expected result, not as a procedure to follow. Given a database or a set of rules, the computer tries to find a solution matching all the desired properties. An archetype of a declarative language is the fourth generation language SQL, and the family of functional languages and logic programming.

Functional programming is a subset of declarative programming. Programs written using this paradigm use functions, blocks of code intended to behave like mathematical functions. Functional languages discourage changes in the value of variables through assignment, making a great deal of use of recursion instead.

The logic programming paradigm views computation as automated reasoning over a body of knowledge. Facts about the problem domain are expressed as logic formulas, and programs are executed by applying inference rules over them until an answer to the problem is found, or the set of formulas is proved inconsistent.

Symbolic programming is a paradigm that describes programs able to manipulate formulas and program components as data.[3] Programs can thus effectively modify themselves, and appear to "learn", making them suited for applications such as artificial intelligence, expert systems, natural-language processing and computer games. Languages that support this paradigm include Lisp and Prolog.[13]

Differentiable programming structures programs so that they can be differentiated throughout, usually via automatic differentiation.[14][15]

Support for multiple paradigms

Most programming languages support more than one programming paradigm to allow programmers to use the most suitable programming style and associated language constructs for a given job.[16]

See also

References

- Nørmark, Kurt. Overview of the four main programming paradigms. Aalborg University, 9 May 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- Frans Coenen (1999-10-11). "Characteristics of declarative programming languages". cgi.csc.liv.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2014-02-27. Retrieved 2014-02-20.

- Michael A. Covington (2010-08-23). "CSCI/ARTI 4540/6540: First Lecture on Symbolic Programming and LISP" (PDF). University of Georgia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-07. Retrieved 2013-11-20.

- "Programming paradigms: What are the principles of programming?". IONOS Digitalguide. 20 April 2020. Archived from the original on Jun 29, 2022. Retrieved 2022-05-03.

- Peter Van Roy (2009-05-12). "Programming Paradigms: What Every Programmer Should Know" (PDF). info.ucl.ac.be. Retrieved 2014-01-27.

- Peter Van-Roy; Seif Haridi (2004). Concepts, Techniques, and Models of Computer Programming. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-22069-9.

- Frank Rubin (March 1987). "'GOTO Considered Harmful' Considered Harmful" (PDF). Communications of the ACM. 30 (3): 195–196. doi:10.1145/214748.315722. S2CID 6853038. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 20, 2009.

- Harper, Robert (1 May 2017). "What, if anything, is a programming-paradigm?". FifteenEightyFour. Cambridge University Press.

- Krishnamurthi, Shriram (November 2008). "Teaching programming languages in a post-linnaean age". ACM SIGPLAN Notices. ACM. 43 (11): 81–83. doi:10.1145/1480828.1480846. S2CID 35714982..

- Floyd, R. W. (1979). "The paradigms of programming". Communications of the ACM. 22 (8): 455–460. doi:10.1145/359138.359140.

- Soroka, Barry I. (2006). Java 5: Objects First. ISBN 9780763737207.

- "Mode inheritance, cloning, hooks & OOP (Google Groups Discussion)".

- "Business glossary: Symbolic programming definition". allbusiness.com. Retrieved 2014-07-30.

- Wang, Fei; Decker, James; Wu, Xilun; Essertel, Gregory; Rompf, Tiark (2018), Bengio, S.; Wallach, H.; Larochelle, H.; Grauman, K. (eds.), "Backpropagation with Callbacks: Foundations for Efficient and Expressive Differentiable Programming" (PDF), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 31, Curran Associates, Inc., pp. 10201–10212, retrieved 2019-02-13

- Innes, Mike (2018). "On Machine Learning and Programming Languages" (PDF). SysML Conference 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-09-20. Retrieved 2019-02-13.

- "Multi-Paradigm Programming Language". developer.mozilla.org. Mozilla Foundation. Archived from the original on 21 August 2013.