Murder of Marcia Trimble

Marcia Virginia Trimble was a nine-year-old girl who disappeared on February 25, 1975, while delivering Girl Scout Cookies in the affluent Green Hills area of Nashville, Tennessee, United States. Her body was discovered 33 days later on Easter Sunday near the Trimble family home. She had been sexually assaulted. During the early years of their inquiry into the assault and murder, the police persisted in investigating one particular suspect, finally charging him in 1979 but he was released in 1980 for lack of evidence.

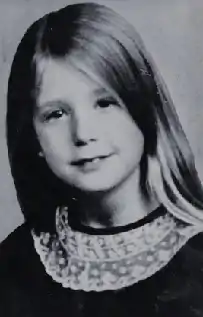

Marcia Trimble | |

|---|---|

Marcia Trimble, c. 1975 | |

| Born | Marcia Virginia Trimble March 28, 1965 |

| Died | February 25, 1975 (aged 9) Nashville, Tennessee |

| Cause of death | Strangulation |

| Occupation | Student |

| Known for | Murder victim |

In 2008, 33 years after the killing, Jerome Sydney Barrett – not the person police had pursued in the 1970s – was charged with Trimble's assault and murder after DNA evidence recovered from her remains linked him to the crime. Barrett had been arrested just days after Trimble's disappearance on suspicion of an unrelated sexual assault and was still in jail when Trimble's body was found. Despite this and his convictions for attacks on other women and children, police had not investigated him in relation to the murder. On July 18, 2009, a jury convicted him for the killing and he was sentenced to 44 years in prison.

Trimble's murder occurred soon after two other crimes linked to Barrett:

- On February 2, 1975, Sarah Des Prez, a Vanderbilt University student, was murdered near the university, which is located close to Green Hills. Barrett was linked to this crime at the same time that his DNA was linked to Trimble's murder.

- On February 17, 1975, a Belmont University student was raped in Nashville. Barrett was arrested in March 1975, in connection with this crime. He was convicted a year later.

Early murder investigation

Marcia Trimble disappeared while delivering Girl Scout Cookies in Green Hills, an affluent neighborhood in Nashville, Tennessee. The disappearance was investigated by local and state police; the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) soon joined the investigation due to the possibility of kidnapping. Trimble's body was discovered more than a month later. It was found that she had been sexually assaulted before being killed.

Investigators searched the neighborhood, believing it likely that the murderer was a local resident. Police attention soon focused on Jeffrey Womack, a 15-year-old boy who lived near the Trimble home and one of the last people to see her alive.

Trimble had come to Womack's house the day of her disappearance. Womack said that he had sent her away because he did not have money to buy cookies. He said that, after he learned of the girl's disappearance, he went to her house to tell the police there what he knew. According to Womack, the police aggressively questioned him and then made him empty out his pockets. Inside the pockets, police found a half roll of pennies, a five-dollar bill, and a condom. This seemed to contradict Womack's testimony that he lacked the money to pay Trimble. (He was turning her away without being rude.) The condom suggested to police that he may have sexually abused Trimble. Womack later said that he had the condom because he was having a sexual relationship with a local woman.

According to Womack, his mother and a neighbor found out that the police were questioning him and insisted that any further interrogation must be done with a lawyer present.

Reporter Demetria Kalodimos believed that Womack's decision to call a lawyer made police more suspicious of him. They felt that an innocent person had no need of a lawyer. Womack's attorney, John Hollins, advised him to stop cooperating with police. After that, Womack refused to discuss the case with either the police or the media.

Unable to obtain a confession, the police resorted to other means to try and gather evidence against Womack. When Womack was 17 years old and working as a bus boy in a restaurant, the police sent an undercover officer into the restaurant to befriend him, but they did not get any incriminating evidence. Womack passed two polygraph tests. In 1980, authorities finally arrested him for Marcia Trimble's murder, but the charge was dismissed for lack of evidence. Many police officers involved in the case continued to believe that he was guilty.[1]

DNA samples were taken from semen collected from Trimble's body, but these samples were stored improperly and deteriorated over time, limiting investigators' ability to identify or exclude suspects. Police collected DNA samples from 96 suspects, including Womack, but none of these samples matched the DNA found in the semen.

Evidence found

Investigators said they believed more than one man's semen was found inside Trimble's body. Semen also was found on her clothes. Investigators believed Trimble had been lured into a garage and killed there. Her body was found fully clothed next to bags of fertilizer in the garage. Despite having been deceased for a month, there was little decomposition, due to the cool, dry environment.

The cause of death was determined to be strangulation because Trimble had suffered a broken hyoid bone.

Police found it difficult to determine how many people were involved in the crime. They believed the perpetrator was a juvenile and someone Trimble knew. Dirt that was found on her shoe was mainly upon the sole, indicating that she had walked into the garage, and had not been dragged into it.

Semen was found on the girl's blouse and pants but not on her underwear. Semen was also found in her vagina, but there was no other sign of rape or penetration. Investigators believed Trimble's attacker was either an adolescent boy or a man with a very small penis. DNA tests seemed to indicate there was semen from as many as four different attackers. One investigator doubted this because the samples had been poorly preserved. "I'm not confident in the DNA sample that we've got," Nashville homicide detective Tommy Jacobs said.[2]

Theories pursued by investigators

In 2001, a local paper interviewed Police Captain Mickey Miller, former homicide detective Tommy Jacobs of the Nashville Police, and former FBI agent Richard Knudsen about the unsolved Trimble case. Each had a different theory about what had happened on the evening when Trimble disappeared.

Captain Miller said that while Trimble was killed in the garage where she was found, that may not have been where she was sexually assaulted. Miller thought that Trimble might have been sexually assaulted at a tree nursery which became part of the investigation. Citing DNA evidence, he also believed that she was sexually assaulted by up to three boys.[3]

Jacobs was not sure that Trimble left her home to deliver cookies to Marie Maxwell. He suggested she might have been planning to meet up with Womack. Jacobs said he thought that someone Marcia knew lured her into the garage. He did not know if it was Womack or just an "adolescent teenager with his hormones blitzing." "The suspect just raped someone. It was probably a new experience for him, and it was a new experience for Marcia. It was a tense situation. Marcia screamed. I don't think the perpetrator wanted to kill her. I think he wanted to gain control of her and make her be quiet."[4] In contrast to Miller (his former boss), Jacobs did not believe that Marcia was sexually assaulted by more than one person.[3]

The FBI's Knudsen posed a different theory. He said that Marcia had walked to Marie Maxwell's home as the woman was pulling into her driveway. Given the timing, Marcia could not have known that Maxwell was returning home unless someone had called to tell her. Just minutes earlier, Maxwell had parked her car in front of a neighbor's driveway to ask a quick question. That house was across the street from the Womack and Morgan homes. If Jeffrey Womack was home during that time, or if he was at Peggy Morgan's house, he could have seen Maxwell's car and called to Marcia. Knudsen placed Womack at the driveway with Marcia.[3]

The three investigators' theories varied widely, but they concluded that whoever killed Marcia most likely was a juvenile who lived in the neighborhood.

Indictment of Jerome Barrett

On June 6, 2008, a Davidson County Grand Jury indicted 60-year-old Jerome Sydney Barrett, charging him with first-degree murder and felony in the case of Marcia Trimble. Barrett had formerly been indicted and convicted for other assaults against women and children. At the time of Marcia's murder, Barrett was working in her neighborhood.[5][6]

Barrett first took responsibility for the 1975 murder during a private conversation on the rooftop of the Davidson County Criminal Justice Center. During questioning, "He said he did not rape her. He killed her." "He said his DNA was on her, but not in her." Barrett once again claimed to have killed Marcia immediately after he had had an altercation with another jail inmate. It was during this altercation, the convict said, that Barrett claimed to have killed "four blue-eyed bitches."

Journalists revealed that, for more than a decade, investigators had concealed the fact that DNA evidence excluded numerous neighbors as potential suspects. A retired police detective admitted that the men were excluded and that they had not been told of the fact.

In the early years of the investigation, the use of DNA evidence was new, and investigators did not thoroughly understand its implications. Investigators were not sure the DNA evidence was conclusive for excluding suspects. In addition, detectives admitted to careless handling of Marcia's body, stating that they simply cut her blouse and pants off in the shed without wearing protective gloves.

Barrett's record

- Sarah Des Prez, a Vanderbilt student, was murdered about three weeks before Marcia Trimble. Metro's Cold Case Unit was able to apply new DNA analysis to evidence from the Des Prez murder to bring charges against Barrett.[5] At the announcement of the arrest of Barrett, police suggested that he might have murdered Marcia. The police said that Barrett's whereabouts and crimes during the period of Marcia's murder had placed him under increased scrutiny.

- On February 17, 1975, a Belmont University student was raped in Nashville. Jerome Barrett was arrested in March, 1975, in connection with this crime. He was convicted of it a year later.

- Barrett had been in jail from March 12, 1975, fifteen days after Marcia's disappearance, until after Marcia's body was found.

- On December 3, 2007, Nashville television stations reported that DNA recovered from the Trimble crime scene matched that of Barrett. "Advances in DNA testing enabled a match between crime-scene evidence and Jerome Barrett, a 60-year-old Memphis man with a criminal record of sexual assaults on both grown women and children."[7]

Impact upon Nashville

Residents were upset by the fact that the victim was a child, and that the crime took place in an affluent neighborhood. This was at a time when people felt that their children were safe.

The delay in finding and recovering the girl's body also disturbed people. FBI agents were brought in to assist with the investigation.[8]

After Womack's release in 1980, residents continued to be haunted by this unsolved murder. Each year, Nashville media highlighted the story on the anniversary of Marcia's disappearance or of the discovery of her body. The case marked a time of great change in how news was covered by local media, and in the emerging importance of DNA evidence (not well understood in earlier years).[8]

Nashville Police Captain Mickey Miller said of the case:

In that moment, Nashville lost its innocence. Our city has never been, and never will be, the same again. Every man, woman, and child knew that if something that horrific could happen to that little girl, it could happen to anyone.[9]

See also

References

- "Transcript - This American Life". www.thisamericanlife.org. 11 October 2013.

- Matt Pulle, "The File on Marcia Trimble Part II," Nashville Scene, 2001-06-28

- Pulle, Matt. "The File on Marcia Trimble",Part I Archived 2009-07-26 at the Wayback Machine, The Nashville Scene and "The File on Marcia Trimble, Part II" Archived 2009-07-26 at the Wayback Machine, The Nashville Scene, June 21 and 28, 2001

- "The File on Marcia Trimble Part II". Nashville Scene. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- E. Thomas Wood and Ken Whitehouse, "Arrest made in Trimble case". NashvillePost.com. 2008-06-06. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- "Arrest in Girl Scout's 33-Year-Old Murder Jolts City". Fox News via Associated Press. 2008-09-22. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- E. Thomas Wood and Ken Whitehouse, "News analysis: Is it really over?". NashvillePost.com. 2007-12-07. Archived from the original on 2008-09-28. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- E. Thomas Wood, "Nashville now and then: A moment of closure?". NashvillePost.com. 2007-12-07. Archived from the original on 2008-09-29. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- Metro Nashville Police Department public statement, April 17, 2002

External links

- Thomas, Susan, "City lost its innocence with Marcia Trimble's murder", The Tennessean, February 25, 2001

- Pulle, Matt. "New Clues, Old Questions", The Nashville Scene, April 25 - May 1, 2002

- Demsky, Ian. "FBI to retest evidence from Marcia Trimble murder", The Tennessean, March 31, 2004

- WKRN Channel 2 News "Man Arrested For 1975 Vanderbilt Rape, Questioned In Another", WKRN News, November 21, 2007

- Bottorff, Christian. "Man investigated in Trimble case", The Tennessean, November 22, 2007

- WSMV Channel 4 News "Police To Make Arrest In Marcia Trimble Case", WSMV News, December 3, 2007

- Sutton David "Marcia Trimble Neighborhood with Photos Then and Now", Bing Maps, April 20, 2009

- Kalodimos, Demetria. Indelible: The Case Against Jeffrey Womack Archived 2013-01-18 at the Wayback Machine, WSMV.com, November 17, 2012. This 117-minute documentary film, fully available online, relies upon:

- documents from the Metro Nashville Police Department's case file

- photos obtained from the Trimble and Womack families

- audio from the police wiretap of the Trimble family telephone revealing the police mistakes and misconduct which led to the targeting of Womack as a suspect. In the documentary film and a simultaneously published book, The Suspect: A Memoir (co-authored with attorney John J. Hollins Sr.), Womack speaks publicly about his experiences for the first time.