Murder of William de Cantilupe

The murder of Sir William de Cantilupe, who was born around 1345, by members of his household, took place in Scotton, Lincolnshire, in March 1375. The family was a long-established and influential one in the county; de Cantilupes traditionally provided officials to the Crown both in central government and at the local level. Among William de Cantilupe's ancestors were royal councillors, bodyguards and, distantly, Saint Thomas de Cantilupe.

De Cantilupe's death by multiple stab wounds was a cause célèbre. The chief suspects were two neighbours—a local knight, Ralph Paynel; and the sheriff, Sir Thomas Kydale—as well as de Cantilupe's entire household, particularly his wife Maud, the cook and a squire. The staff were probably paid either to carry out or to cover up the crime, while Paynel had been in dispute with the de Cantilupes for many years; it is possible that Maud was conducting an affair with Kydale, during her husband's frequent absences on service in France during the Hundred Years' War.

The Treason Act 1351 laid down that the murder of a husband by his wife or servants was to be deemed petty treason. De Cantilupe's murder was the first to come within the purview of the Act, as were the subsequent trials of Maud and several members of her staff. Many people were indicted for the crime, although only two were convicted and, in the end, executed for it. Others were also summoned but, as they never appeared, were outlawed instead. Other influential local figures, such as the sheriff, were accused of aiding and abetting the criminals. The last trial and acquittal was in 1378, although the case had long-term consequences. No motive has been established for de Cantilupe's killing; historians consider it most likely that responsibility rested with de Cantilupe's wife, her lover, the cook and their neighbour, with a mix of motives including love and revenge.

Background

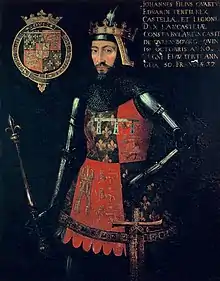

The de Cantilupes[note 1] were a long-established Lincolnshire family based at Scotton in the northeast of the county.[2] They were also major landholders in the Midlands, with estates in Greasley, Ilkeston and Withcall.[3] The family had traditionally played an important role in both local society and central government[4] with a history of loyal and diligent service to the crown.[3][note 2] Not only were they lords of the realm—"one of the richest and most influential families in fourteenth-century England",[7] suggests the scholar Frederik Pedersen—but the family possessed Saint Thomas de Cantilupe in its ancestry, and considered themselves to be under his special protection.[2] William de Cantilupe, 30 years old at the time of his death,[8] was a "knight of some stature" in the region, notes the historian J. G. Bellamy,[9] and by then had been retained by John of Gaunt.[10]

Family tree

The relationships between de Cantilupe, Paynel and Kydale were:[note 3]

| Sir William de Cantilupe, d. 1377 | Joan, dau. of Sir Adam de Welles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Katherine dau. of Sir Ralph Paynel of Scotton, d. 1383 | Sir Nicholas de Cantilupe, d. 1370 | Sir William de Cantilupe, d. 1375 | Maud, dau. of Sir Philip Nevil of Scotton | Sir Thomas Kydale, d. 1381 | Sir John Bussey, d. 1399 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Household

Although the de Cantilupe family's main residence was Greasley Castle, Nottinghamshire, in the spring of 1375 William was staying at the manor of Scotton. This estate had come to him through his marriage to Maud Nevil, daughter of Sir Philip Nevil of Scotton.[12]

The household, as named in later indictments, comprised: William de Cantilupe and his wife Maud; Maud's maid, Agatha Lovel;[note 4] Richard Gyse, squire; Roger Cooke,[note 5] the cook[13] (who may also have been the butler or "botiller"); Robert de Cletham, the seneschal; Augustine Morpath; John Barneby de Beckingham; John de Barnaby,[note 6] the household chamberlain; William Chaumberleyn;[note 7] John Chaumberleyn;[note 8] Walter de Hole;[note 9] Henry Taskare; Augustine Forster;[note 10] Augustine Warner and John Astyn.[13] Gyse and Cooke may have been impoverished, suggests Pedersen, and so ripe for recruitment as de Cantilupe's killers.[14][15]

Death of de Cantilupe

A later jury established that de Cantilupe was "at peace with God and the lord king", and Pedersen has taken this to indicate that he had prayed, and, therefore, was about to retire for the night.[10] In a premeditated and minutely planned attack,[16] de Cantilupe was stabbed to death with many blows. The precise date of the crime is unknown; the juries that heard the indictments offered dates varying from 13 February to 11 April 1375.[9] Pedersen has suggested the evening of Friday, 23 March[17] or the following Friday, as most probable.[8] Five of the seven quarter sessions juries which subsequently sat suggested the latter, the other two decided it was the former date.[18][note 11]

It was probably the maid, Lovel, who gave Cooke and Gyse access to de Cantilupe's room.[19] Having killed him, according to the later court records, they washed his corpse "with heated-up water so that they not be discredited by the effusion of the blood of his wounds".[19] The hot water cauterised de Cantilupe's wounds and (it has been suggested) made his body easier to transport;[20] it also, suggests Pedersen, implies that they had assistance from the house's domestic staff, and, by extension, that the "entire household was involved in aiding and abetting the murder".[19] He argues that

The boiled water would have had to be carried through the manor from the kitchen to William's bed-chamber either before the murder (and thus be prepared ahead of time, implying premeditation) or have been carried in full view of the servants after the murder (thus implying their complicity).[19]

— Frederik Pedersen

The corpse was placed in a sack, and the killers transported it seven miles (11 km) to the east, dumping it near Grayingham.[21] Here they dressed the corpse in "fine garments",[9] including a belt and spurs. Pedersen speculates that this was to present the appearance of an attack by highwaymen[21] or footpads.[9] The body was discovered by passers-by, who reported that, in their view, he had been killed on the road.[16] The discovery may not have occurred for some time though, or at least not have been reported, argues Bellamy, which may account for the number of possible dates on which the crime could have been committed.[22]

The attempt to foist guilt upon highwaymen was a piece of cool calculation and the dressing up of William's body while rigor mortis set in shows a cold-blooded attitude to the job which would be impressive were it not so horrific.[16]

Graham Platts

Escape

Immediately after the murder, it appears that the entire house was closed up and its staff dispersed. Pedersen suggests this was what originally indicated to the authorities that something was amiss.[19] Four members of the household were later alleged to have sought refuge with Sir Ralph Paynel, whose manor was 90 miles (140 km) north of Scotton. Those who apparently escaped to Paynel's house were Maud, Lovel, Gyse and Cooke.[21] Paynel was an important figure in Lincolnshire society, and had been a retainer of King Edward III, although Pedersen describes him as something of a "loose cannon",[note 12] due to Paynel's having been summoned several times to answer allegations of excess.[25][note 13]

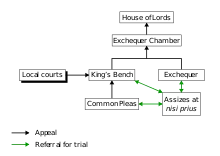

Indictments, trials and convictions

Although most of the household were later indicted for de Cantilupe's killing, it is not known who was in charge of the operation. The medievalist Rosamund Sillem has identified Paynel as the conspiracy's mastermind,[30] for example, while Pedersen has argued that "there is a strong circumstantial case to be made that they were acting under the direction of William's wife, Maud Nevil".[21]

Sessions of the Peace

The case came before the commission of county coroners,[16] headed by the sheriff, Thomas Kydale of South Ferriby,[31][32] on 25 June 1375.[16] Several charges were presented and many suspects arraigned.[21] Maud was named as a party,[9] although in these early proceedings there was some uncertainty as to the role she had played, some juries naming her as an instigator and others as an accessory.[33] Her seneschal, Robert de Cletham, was charged with aiding and abetting her.[18] Ten juries investigated over a period of some weeks. This may indicate a greater than usual effort by the Crown to establish the facts, and perhaps reflects the degree of complexity investigators encountered.[22] The juries presenting to the justices believed the crime was committed around the Feast of the Annunciation.[18] They established few details of the crime, but were the first juries to level charges against the whole household.[18]

Maud accuses

As well as being named a suspect, Maud also lodged her own accusations against 16 men and women.[13] Pedersen argues that, "given her almost certain complicity in the murder it must have come as a surprise to the two assassins, William’s squire, Richard Gyse, and Roger Cooke, that Maud named them as the murderers".[35] Bellamy suggests that an accusation of this nature would have been expected of any woman who was in the house and on the scene when her husband was killed. It would not necessarily have implied complicity to her contemporaries, although it may also have been, says Pedersen, an attempt at diverting suspicion.[22][35] The historian Paul Strohm has argued that, "like other women raising a hue ... she then found herself under suspicion and indictment for complicity".[20][note 15]

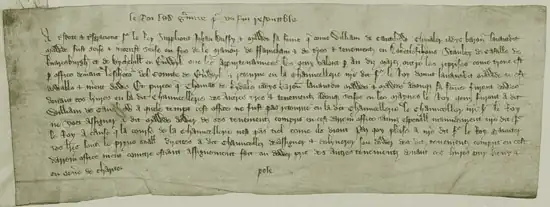

King's Bench sessions

The Court of King's Bench convened in Lincoln on 29 September 1375. Once more Kydale presided.[35] Usually in medieval indictments the accused ranged from "unknown felons [to] notorious robbers";[9] the accusations against 15 members of de Cantilupe's household, Maud herself[16] and an important local figure such as Sir Ralph Paynel were exceptional.[13] Both the indictments of the peace sessions and Maud's June allegations were presented to the bench, and Gyse and Cooke were arraigned.[13] Whereas the juries which presented their conclusions to the peace commission believed the crime was committed around the Feast of the Annunciation, it is with the juries presenting to the bench that a dating disparity is introduced. The King's Bench juries suggested, between them, 10 different dates spread over two months. Sillem suggests that this may be explained by the fact that, by the time they came to consider the evidence, they could only rely on memories to an event which occurred at least six months previously.[18][note 16]

When the case was eventually heard, it was not as murder, but as petty treason, since it involved either household servants rebelling against their master, or a wife against her husband,[16] and was the first time the 1351 Treason Act had been used against members of a household in the death of their master.[38][note 17] The King's Bench juries deliberately used the language of treason rather than felony: tradiciose, false et sediciose, seditacione precogitata: treason, lies and sedition, seditious aforethought. All of which, argues Sillem, suggested to observers this "conveyed that most heinous of crimes, treachery to the lord".[18]

Maud withdrew her allegations—paying a fine (having made them) for doing so[35]—and Gyse and Cooke were therefore acquitted on her charges. The jury indictments remained, however.[13] Most of those she had accused in June had never presented themselves to court—they seem to have disappeared—and apart from Cooke and Gyse, only she and her husband's seneschal stood trial.[38] De Cletham had been charged only with aiding and abetting by the peace sessions juries but, at the bench, he was also charged with murder, as Maud had been. They were acquitted on both that charge and one of aiding and abetting Gyse and Cooke.[39] Maud and de Cletham were released on a bond of mainprise on the charges of aiding and abetting those other principals who had failed to appear.[note 18] Paynel was charged with harbouring Maud, Lovel, Gyse and Cooke[9][16] on his Caythorpe manor, and also released on mainprise until Michaelmas the following year.[39] The only accused to be found guilty before the bench were Gyse and Cooke.[18]

Westminster sessions

The case moved to the King's Bench at Westminster in September 1376.[39] Members of the de Cantilupe household who had failed to appear in court were outlawed as felons.[9][note 19] Maud and the seneschal, though, were acquitted on the charge of having aided and abetted them.[39] Paynel was again indicted for harbouring criminals.[9][16]

Kydale, Paynel and Lovel

The sheriff, Kydale, was also suspected of complicity in the crime due to his standing surety for Maud during her appearances.[16] He was already associated with Paynel, and this may have hardened suspicions against him.[22] One of Kydale's duties as sheriff was to select the juries that sat on the case, and by extension, that would decide Maud's guilt or innocence.[33]

The longest trial to take place was that of Paynel. Indicted at Lincoln in 1375, he was released on mainprise until September. He was then not tried for another six months. At the Easter term King's Bench sessions held at Westminster in 1376 he was released nisi prius.[44][note 20] Kydale was the sheriff who appointed the jury that released Paynel on mainprise, but Kydale's term ended in September 1375. As Paynel had been appointed sheriff in September 1376, he was in charge of overseeing the transfer of his own case to London.[45][32] In the event, Paynel was acquitted in the last few months of his shrieval term, which expired in October.[14][note 21] Paynel was replaced as sheriff by Kydale, whose second term of office lasted until 1378.[46]

Sillem says that "a certain amount of mystery surrounds Agatha"[13] the maid. Both she and Maud had been accused as both principals and accomplices—court records describe her as "notoriously suspect" in the crime[13]—but "like so many of the accused, she failed to appear in court".[39] Nothing is known of her as a person outside the de Cantilupe case, and her surname alternates in the documents between Lovel and Frere. In her case, though—unlike so many of her comrades—her reason for not appearing has been established. On Monday 27 August 1375[13] she escaped the immediate dispensing of justice by bribing her gaolers in Lincoln Castle, where she had been imprisoned awaiting trial.[44][note 22] The castle bailiffs, Thomas Thornhaugh and John Bate, were later arrested and tried for allowing Agatha to escape justice. Thornhaugh produced witnesses who swore he was innocent of the offence;[44] he was acquitted of felony but fined for dereliction of duty.[13] Pedersen reports that Bate "provided a somewhat more unusual defence".[44] Accused in July 1377 of accepting £10 to allow Agatha to flee, he produced a pardon from the new king, Richard II, absolving Bate from any malfeasance of office, and a second pardon, dated the 8th of the same month, from the late king Edward III.[44][note 23]

Cooke and Gyse

Cooke and Gyse were charged of having with sedicioni precogitale ... interfecerunt et murdraverunt ("sedition aforethought ... killed and murdered") their master.[50][note 24] As such, they were tried and subsequently convicted of petty treason.[21] No motive was ever established for their role in the killings. The archivist Graham Platts notes that "the affair was so complicated that no convictions for murder were made".[16] Although they had disappeared following their escape to Paynel's, in 1377 they were apprehended for the murder and executed for the crime (by being drawn and hanged).[35] It is possible that they expected protection that never came. Pedersen suggests they may have been promised a form of insurance by their social betters against capture and conviction, or that if that occurred, they would be treated leniently and their families "looked after in case [Gyse and Cooke] were not able to flee the country".[35]

Motive

Although no motive was established by the courts for the killing, historians have generally considered that Maud was romantically involved with Kydale and that they had de Cantilupe killed to facilitate their marriage.[38] Sillem noted the close connection between Kydale and Paynel—between 1375 and 1378, she says, they "must have practically controlled the affairs of Lincolnshire"[51][note 25] —and argues that they both had a motive for de Cantilupe's death. Kydale's, she suggests, was that he wanted to marry Maud while Paynel wanted revenge for his perceived previous ill-treatment at the hands of the de Cantilupe family.[51] De Cantilupe had been serving abroad in the years before his death, and it is possible that Maud and Kydale had begun a relationship in his absence.[note 26] But the others' motives are more obscure, argues Pedersen. Regarding Ralph Paynel, for example:

The literature has accepted that he probably played a crucial role in the murder, and that he was pivotal in ensuring that most of the persons involved in the crime avoided the censure of the law. But his reasons for becoming involved in the first place have been unclear.[54]

— Frederik Pedersen

Paynel "was no doubt acutely aware of the multitude of insults he had received at the hands of the de Cantilupes",[2] which went back to at least 1368. In that year de Cantilupe's elder brother, Nicholas, accused Paynel and his chamberlain of leading an armed force and attacking the de Cantilupe caput baroniae at Greasley Castle.[55] He further accused Paynel of raping Nicholas's wife, Katherine. She, however, was Paynel's daughter, and far from ravishing her, notes Pedersen, Paynel was rescuing her:[56][note 27] de Cantilupe had imprisoned his wife in the castle after she launched an annulment suit against him. This was on the grounds of impotence, and was heard before the Archbishop of York.[56][note 28] Nicholas died in Avignon a few months later while lobbying Pope Urban V to annul his wife's case[note 29] and William inherited his brother's property. Nicholas's death was deemed suspicious, and William was arrested on suspicion of poisoning his brother with arsenic. William was on royal service in Aquitaine at the time,[61] and Pedersen notes that "the suspicion had clearly been strong enough for the King to provide an expensive armed guard to ensure that William answered for his alleged crime in London". He was held in the Tower of London during the council's investigation, which seems to have concluded that Nicholas's death was from natural causes.[62] William took livery of his lands in September 1370.[note 30] In December he also successfully claimed three manors from Paynel[62] that had originally been Katherine's dower. This, combined with the insult to his daughter, may have been sufficient cause for Paynel to plot against William as he had his brother.[56]

Later events

Cooke and Gyse have been described as "remorseless" in the planning of the killing and its execution.[16] They were the only individuals to suffer punishment in connection with de Cantilupe's murder. Others escaped, either through complicated manipulation of the law and jury rigging—for example Maud, Kydale and Ralph—or simpler, more traditional methods, such as Agatha's prison break.[44] In the case of most of the household, no information survives on their fate or sentence. William de Hole, for example, is never mentioned on any subsequent extant court or legal document. For most of those outlawed, it is unknown whether they ever appealed their outlawry, were captured or subsequently pardoned.[39] Although they probably remained outlawed for their absence from court, all—including Paynel—were acquitted in 1377 of harbouring criminals.[9] Bellamy suggests that the reason the household workers ran away in the first place was probably down to the infamy the case had engendered, as a direct result of which, he says, "juries were more likely than usual to find the accused guilty".[22] Paynel eventually joined John of Gaunt's retinue and became a valued servant to Richard II.[67]

The case was a cause célèbre of its day.[16] Not only had it effectively ended a family which, in Sillem's words, had "played a considerable part in English history",[68] but the killing of a man by either his servants or his wife—or both—"was regarded as particularly heinous by all ranks of society".[22] On his death de Cantilupe was the last of his line, and the family died out.[38] There being no remaining male heirs, the de Cantilupe estates were broken up between two senior branches of the family, represented by the de Cantilupe brothers' cousins, William, Lord de la Zouche and John Hastings, who was then a minor.[15]

Kydale married Maud—by now "notorious"[69]—after her acquittal.[16][note 32] Their marriage was to be short-lived, as he was dead by November 1381.[70] The following year Maud married Sir John Bussy.[71] She was now a wealthy woman, bringing both large estates in her own right as well as dowers from her previous husbands.[note 33] The medievalist Carol Rawcliffe suggests that "whatever apprehensions Bussy may have felt in following the short-lived Kydale as her third husband were clearly overcome by the prospect of a greatly increased rent-roll".[69][note 34]

Maud—whom Rawcliffe described as "in her own way, as colourful a character as Bussy himself"—died in 1386.[71][69] The murder cast a long shadow for her and William's staff. In what Sillem calls a "curious exception" to the unknown fates of most of those who had been outlawed, at the supplication of Queen Anne in 1387, King Richard pardoned John Tailour of Barneby, Cantilupe's steward. Sillem believes that this pardon, "so many years after the event and to apparently only one of the outlaws adds yet another element of mystery".[39]

Historiography

Sillem's analysis of the Lincolnshire plea rolls in 1936 was the first major study of de Cantilupe's murder.[note 35] She highlighted how the case not only demonstrated contemporary approaches to crime and petty treason but also provided a wealth of information on the more mundane aspects of society, such as the organisation of a late-14th century magnatial household.[18] Her conclusion—that the murder was planned by Maud and Kydale with Paynel's assistance—led her to propose a pre-existing romantic connection between the first two, but she was unable to establish a motive for Paynel's involvement.[30] Sillem's analysis has mostly been followed by historians of the later-20th century,[69] although the lack of evidence as to most of the individuals' roles means that there are variations upon the theme. Rawcliffe, for example, suggests that Maud's lover was within the household—and so not Kydale—and that:[69]

Having almost certainly murdered her first husband, Sir William Cantilupe [sic], with the assistance of a young lover and other members of her household, she charmed the sheriff of Lincolnshire first into helping her to obtain a royal pardon and then into actually marrying her.[69]

— Carol Rawcliffe

The case was "notorious", says Bellamy, as an example of carefully planned premeditated murder,[50] planned with sufficient subtlety to thoroughly hinder the crown's ability to investigate.[22] Platts has compared the killing of de Cantilupe to the "kind of plotting in which Shakespeare's audiences revelled" two and a half centuries later,[16] while Bellamy suggests it "contained elements of the modern murder drama".[9] Not least, argues Bellamy, because of the transporting of the corpse and the attempt at blaming highwaymen, elements of crime which "are rarely found in medieval records".[22] Strohm has highlighted the role of Maud in public perception, noting how it fed into the popular perception of women generally and Maud specifically being "schemers and unworthy daughters of Eve working through gullible male accomplices seem to underlie many of the household treason narratives".[20][note 36]

He also notes that of the numerous cases in which women are executed for killing their husbands in the latter half of the 14th century, there is only one surviving example of a wife acting on her own, without the assistance of either neighbours, family or household.[73][note 37]

Pedersen has described the manipulation of the legal machinery as near "virtuosic",[75] and wondered whether Maud—assuming she was a guilty party—double crossed her accomplices. Perhaps, he queries, Gyse and Cooke being "neither wealthy nor influential had something to do with it".[35][note 38] Pedersen suggests that not only was de Cantilupe's murder cleverly planned over a long period, "it also bears all the hallmarks of ... having been put on hold until everybody was in positions of power where they could cover for each other."[44] Apart from Gyse and Cooke, he comments, everybody else involved "got away with murder".[44]

Notes

- Also written as de Cantilupo, Cauntiloue, Cauntelou, Cantiloue, Cauntilieu, Cantelo and Canteloo in the various legal records.[1]

- William's ancestors sat on the King's Bench at Westminster,[4] acted as curial sheriffs in the regions[5] and at least one was steward of the royal household.[6]

- The pared-down de Cantilupe family tree as described by Cokayne.[11]

- Sometimes Agatha Frere.[13]

- Sometimes Coke.[13]

- Also John Tayllour de Barnaby.[13]

- Sometimes Walter; also Chaumberleynman.[13]

- Also surnamed Henxteman.[13]

- Or Hayle.[13]

- Or Forester.[13]

- Sillem cautions that this divergence in dating "makes one wonder if their information on other points was equally reliable";[18] Bellamy, similarly questioned, "we may wonder if all the other details reported by the jurors were at all accurate".[9] Sillem suggests the anomaly could be down to something as simple as a scribal error, miswriting poste for ante, for example, as the two Fridays are the nearest before and after the Feast of the Annunciation.[18]

- He also, notes Pedersen, had a history of sheltering people from the law, as a few years earlier two of his servants were accused of killing a man in London and had taken refuge in their master's house. King Edward III had ordered the sheriff "to stay until further notice the taking of...Ralph Paynel by reason of his entertaining John Courcy and John de Scotton indicted for the death of Roger de Keleby".[23] This behaviour has led Pedersen to argue that Paynel was clearly "not averse to taking risks and that he was loyal to his servants".[24]

- The precise nature of Paynel's "excesses" are not always known, although contemporary legal records exist that show him as both accused and accuser.[26] In March 1355, for example, he was indicted for "divers trespasses and excesses", which the King wished his council to personally examine.[27] In September 1362 Paynel was involved in a local feud which resulted in his servant accidentally killing a man,[28] while three years later Paynel accused members of the local gentry of having "broke his close, carried away his goods and assaulted his servants",[29]

- This illuminated manuscript from about 1460 is the earliest known depiction of the court.[34]

- The social historian Barbara Hanawalt, for example, cites the example of a woman in Buckinghamshire who, having raised the hue and cry against a killer was then arrested and charged with larceny and theft herself.[36]

- These presentments are contained on Roll LL of the 1360–75 county peace commission records covering seven separate entries.[37] The discrete dates suggested by the King's Bench juries were 13 and 23 February; 9, 13, 16, 19 and 31 March; 5, 6, 11 April.[18]

- The 1351 Statute of Treason codified the killing of a master by a servant as petty treason, although the crime was rare.[18] Platts argues that "the killing of a master by a servant was a rare occurrence, it struck at the root of a fundamental relationship within feudal society and as such the de Cantilupe murder was not just treason but an act of anarchy".[16] Petty treason was the only form of treason which Justices of the Peace were able to hear in this period,[37] and Sillem notes that the de Cantilupe case contains two out of the three definitions under the 1351 act.[18]

- Mainprise was a form of bail, in which a person was released on condition of reappearing in court on payment of a bond by others' guarantee. Unlike bail, under which they officially remained in custody and could be arrested at any time, release under the writ de manucaptores effectively withdrew custody from the individual until the judicial hearing.[40][41]

- In English common law, an outlaw was a person who had defied the laws of the realm, by such acts as ignoring a summons to court, or fleeing instead of appearing to plead when charged with a crime.[42]

- On account of the case already having been heard at the Lincoln assize.[44] The term—Latin for "unless before"—stems from the wording of the writ used to summon cases. As the legal scholar Roscoe Pound records:[43]

The sheriff of the county where the venue lay was commanded to cause twelve good and lawful men of the vicinage to come to Westminster to give their verdict on the issue by a certain date unless before that time (nisi prius) the justices of assize came into the county.[43]

- Far from Paynel improving his reputation, Pedersen notes that "complaints continued to be heard in London concerning his abuses of power right up to his death in 1383".[14]

- Sillem has commented on the rarity for a woman to be accused as Agatha was, noting that she found "no other recorded instance, and the lawbooks offer no information".[47]

- Edward III had died on 21 June 1377; his eldest son, the Black Prince had predeceased Edward, so his grandson Richard had become king while a minor.[48][49]

- This became favoured legal terminology in the 15th century, but the de Cantilupe case, according to the historian J. G. Bellamy, is the first recorded use of it.[50]

- Sillem comments that the county's political class was not particularly extensive, "even when due allowance is taken for the smallness of the medieval population, for the same men served again and again" in the various royal offices, and further, were connected by marriage, as the Paynels and de Cantilupes had been.[52]

- Although Kydale had also served in France under the Earl of Hereford in 1372.[53]

- Nicholas de Cantilupe alleged that as well as the abduction of his wife, Paynel had caused much damage to the house and had stolen plate and jewels worth £2,000. Furthermore, notes, Pedersen, his "inability to defend his castle against assailants armed with 'sticks, bows and arrows' may have been acutely embarrassing".[56]

- The records of de Cantilupe's annulment case are still extant, and are housed in the Borthwick Institute's archives at the University of York, classified as Cause Paper E 259.[57] They comprise 16 records, and include 10 depositions from seven witnesses.[58] Katherine claimed that Nicholas had no genitalia—which caused "great disbelief and consternation", says Pedersen, and to which Nicholas reacted with threats and the violence, and refused to appear before the court.[59]

- Between 1309 and 1376 there was a papal schism between popes loyal to either of the two major European powers. Those loyal to the French crown resided at Avignon, while popes loyal to the Holy Roman Empire remained in Rome.[60]

- The feudal system was based on the premise that all land belonged to the king, and that other men—tenants-in-chief, such as the de Cantilupes[63]—held their land from him. Heirs had to apply for legal recognition of their rights before they could enjoy them.[64] The king would hold the estates until the heir applied for livery of seisin: the right to enter his estates. Possession was usually obtained by paying a fine to the exchequer.[65]

- Held at The National Archives, Kew, and classified as SC 8/222/11086.[66]

- They had married by 4 October 1379, when Kydale paid a fine for marrying without the King's permission.[33]

- The English legal concept of dower had existed since the late twelfth century as a means of protecting a woman from being left landless if her husband died first. He would, when they married, assign certain estates to her—a dos nominata, or dower—usually a third of everything he was seised of. By the fifteenth century, the widow was deemed entitled to her dower.[72]

- Bussy was to have a profitable career under Richard II, but as a pillar of the regime, he did not survive Richard's deposition in 1399 and Henry Bolingbroke's accession as Henry IV: Bussy was beheaded in Bristol Castle within weeks of Henry's landing.[71][69]

- Sillem notes that until her study—and despite contemporary records such as the Charter Rolls and the Inquisitions post mortem holding "ample evidence"—previous historians, such as those who wrote the entries on the de Cantilupe family for the Dictionary of National Biography or the revised Complete Peerage omit all mention of the 1375 murder.[1]

- Strohm notes that the converse was also true:

Just as the records suggest ingrained suspicions of women, so do they contain the opposite, idealizations of women as the most steadfast and self-effacing of mourners. When Richard Pope and William del Idle slew their master John Coventry, his wife Elena set a standard of spousal rectitude that is singled out for approving mention, promptly pursuing the fleeing murderers through four neighboring villages and beyond. [20]

- Strohm comments that it is unknown whether this was because the women involved chose it to be this way, or whether "the male judicial system was unable to imagine them functioning any other way".[74]

- The former, the court established, was worth ten shillings and half an acre of land; the latter, nothing.[35]

References

- Sillem 1936, p. lxvi.

- Pedersen 2016a, p. 93.

- Partington 2004.

- Pedersen 2000, p. 145.

- Carpenter 1976, pp. 1, 8 n.1.

- Powicke 1941, p. 305.

- Pedersen 2016b, p. 14.

- Pedersen 2016b, p. 1.

- Bellamy 1973, p. 54.

- Pedersen 2016b, p. 2.

- Cokayne 1913, pp. 112–115.

- Roskell & Clark 1993, p. 449.

- Sillem 1936, p. lxxii.

- Pedersen 2016b, p. 8.

- Sillem 1936, p. lxx.

- Platts 1985, p. 253.

- Pedersen 2016a, pp. 69, 72.

- Sillem 1936, p. lxxi.

- Pedersen 2016b, p. 3.

- Strohm 1992, p. 134 n.11.

- Pedersen 2016a, p. 69.

- Bellamy 1973, p. 55.

- HMSO 1910, p. 144.

- Pedersen 2016b, p. 4.

- Pedersen 2016a, pp. 69, 73.

- Pedersen 2016a, p. 73 n.10.

- HMSO 1896, p. 122.

- HMSO 1937, p. 188.

- HMSO 1912, p. 144.

- Pedersen 2016a, p. 70.

- Sillem 1936, p. lxvix.

- HMSO 1963, p. 79.

- Pedersen 2016b, p. 6.

- Inner Temple 1460.

- Pedersen 2016b, p. 5.

- Hanawalt 1974, p. 263.

- Sillem 1936, p. xl.

- Pedersen 2016a, p. 91.

- Sillem 1936, p. lxxiii.

- Finlason 1869, p. 544.

- Stephen 2014, p. 240.

- National Archives 2020.

- Pound 1944, pp. 328–330.

- Pedersen 2016b, p. 7.

- Pedersen 2016b, pp. 6–7.

- Sillem 1936, p. lxix.

- Sillem 1936, p. lxxiii n.3.

- Ormrod 1990, p. 52.

- McKisack 1992, pp. 392, 397.

- Bellamy 1998, p. 60.

- Sillem 1936, p. lxxiv.

- Sillem 1936, p. lxxvi.

- Holmes 1957, p. 80 n.4.

- Pedersen 2016a, pp. 91–92.

- Arnold 1987, pp. 83–84.

- Pedersen 2016a, p. 71.

- Pedersen 2016a, p. 76.

- Pedersen 2016b, p. 16.

- Pedersen 2016a, p. 78.

- Zutshi 2000, p. 263.

- Cokayne 1913, p. 115.

- Pedersen 2016a, p. 89.

- Wolffe 1971, pp. 56–58.

- Lawler & Lawler 2000, p. 11.

- Harriss 2005, pp. 16–17.

- National Archives 1382.

- Pedersen 2016b, pp. 8–9.

- Sillem 1936, p. lxv.

- Rawcliffe 1993.

- Roskell 1981, p. 47.

- Mackman 1999, pp. 303–304.

- Kenny 2003, pp. 59–60.

- Strohm 1992, p. 129 n.7.

- Strohm 1992, p. 129 n.11.

- Pedersen 2016b, p. 9.

Sources

- Arnold, M. S., ed. (1987), Select Cases of Trespass from the King's Courts, 1307–1399, London: Selden Society, OCLC 159829726

- Bellamy, J. G. (1973), Crime and public order in England in the later Middle Ages, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, ISBN 978-0-7100-7421-8

- Bellamy, J. G. (1998), The Criminal Trial in Later Medieval England: Felony Before the Courts from Edward I to the Sixteenth Century, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-4295-8

- Carpenter, D. A. (1976), "The Decline of the Curial Sheriff in England 1194-1258", The English Historical Review, 91: 1–32, doi:10.1093/ehr/XCI.CCCLVIII.1, OCLC 2207424

- Cokayne, G. E. (1913), Gibbs, V.; White, G. H. (eds.), The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, vol. III: Canonteign–Cutts (2nd ed.), London: The St. Catherine's Press, OCLC 61913641

- Finlason, W. F. (1869), Reeves' History of the English Law: From the Time of the Romans, to the End of the Reign of Elizabeth, vol. II, London: Reeves & Turner, OCLC 867030385

- Hanawalt, B. (1974). "The Female Felon in Fourteenth-Century England". Viator. 5: 253–268. doi:10.1484/J.VIATOR.2.301625. OCLC 819017263.

- Harriss, G. L. (2005), Shaping the Nation: England 1360–1461, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 978-0-19-822816-5

- HMSO (1896). Calendar of the Close Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office: Edward III, 1354–1360 (X ed.). London: Public Record Office. OCLC 53586026.

- HMSO (1910), Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1360–1364 (1st ed.), London: Public Record Office, OCLC 977899061

- HMSO (1912). Calendar of the Patent Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office: Edward III, 1364–1367 (XII ed.). London: Public Record Office. OCLC 2179027.

- HMSO (1937). Calendar of Inquisitions Miscellaneous, Chancery (III ed.). London: Public Record Office. OCLC 465228912.

- HMSO (1963), List of Sheriffs of England and Wales from the Earliest times to A.D. 1831 (reprint ed.), London: Public Record Office, OCLC 217258623

- Holmes, G. A. (1957), The Estates of the Higher Nobility in Fourteenth-century England, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, OCLC 317918203

- Inner Temple (1460), "Manuscript Collection", archived from the original on 22 August 2010, retrieved 26 August 2010

- Kenny, G. (2003), "The Power of Dower: The Importance of Dower in the Lives of Medieval Women in Ireland", in Meek, C.; Lawless, C. (eds.), Studies on Medieval and Early Modern Women: Pawns Or Players?, Dublin: Four Courts, pp. 59–74, ISBN 978-1-85182-775-6

- Lawler, J. J.; Lawler, G. G. (2000) [1940], A Short Historical Introduction to the Law of Real Property (repr. ed.), Washington, DC: Beard Books, ISBN 978-1-58798-032-9

- Mackman, J. S. (1999), The Lincolnshire Gentry and the Wars of the Roses (DPhil. thesis), York, OCLC 53567469

- McKisack, M. (1992), The Fourteenth Century 1307–1399, Oxford History of England, vol. V (repr. ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 978-0-19-821712-1

- National Archives, "SC 8/222/11086" (1382) [Petitioners: John Bussy (Busshy) and Maud Bussy (Busshy), his wife], SC 8 – Special Collections: Ancient Petitions, Series: manuscript, London: The National Archives

- National Archives (2020). "The Outlaw in Medieval and Early Modern England". London: The National Archives. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Ormrod, M. W. (1990), The Reign of Edward III: Crown and Political Society in England, 1327–1377, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-05506-1

- Partington, R. (2004), "Cantilupe [Cantelupe], Nicholas, third Lord Cantilupe (c. 1301–1355)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4567, ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8, archived from the original on 22 April 2020, retrieved 1 October 2018 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Pedersen, F. J. G. (2000), Marriage Disputes in Medieval England, London: Hambledon, ISBN 978-1-85285-198-9

- Pedersen, F. J. G. (2016a), "Motives for Murder: The Role of Sir Ralph Paynel in the Murder of William Cantilupe (1375)", in Simpson, A.; Wilson, L. M.; Styles, S.; West, E. (eds.), Continuity, Change and Pragmatism in the Law: Essays in Memory of Professor Angelo Forte, Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, pp. 68–93, ISBN 978-1-85752-039-2

- Pedersen, F. J. G. (2016b), "Murder, Mayhem and a Very Small Penis", American Historical Association, AHA, pp. 1–32, OCLC 477282618, archived from the original on 22 April 2020

- Platts, G. (1985), Land and people in Medieval Lincolnshire, Lincoln: History of Lincolnshire Committee for the Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, ISBN 978-0-902668-03-4

- Pound, R. (1944). "Legal Profession in England from the End of the Middle Ages to the Nineteenth Century". Notre Dame Law Review. 19: 315–333. OCLC 495288706.

- Powicke, F. M. (1941), "The Murder of Henry Clement and the Pirates of Lundy Island", History, 25 (100): 285–310, doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1941.tb00747.x, OCLC 993085645

- Rawcliffe, C. (1993), "Bussy, Sir John (exec. 1399), of Hougham, Lincs. and Cottesmore, Rutland.", The History of Parliament Online, archived from the original on 2 October 2019, retrieved 2 October 2019

- Roskell, J. S. (1981). Parliament and Politics in Late Medieval England. London: Hambledon. ISBN 978-0-9506882-9-9.

- Roskell, J. S.; Clark, L. (1993), The House of Commons, 1386–1421, vol. Members, A–D, London: History of Parliament Trust, ISBN 978-0-86299-943-8

- Sillem, R., ed. (1936), Records of Some Sessions of the Peace in Lincolnshire: 1360–1375, Publications of the Lincoln Record Society, vol. XXX, Lincoln: Lincoln Record Society, OCLC 29331375

- Stephen, J. F. (2014) [1883], A History of the Criminal Law of England, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-108-06071-4

- Strohm, P. (1992). Hochon's Arrow: The Social Imagination of Fourteenth-Century Texts. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6305-1.

- Wolffe, B. P. (1971). The Royal Demesne in English History: The Crown Estate in the Governance of the Realm from the Conquest to 1509. Athens, GA: Ohio University Press. OCLC 277321.

- Zutshi, P. N. R. (2000). Jones, M. (ed.). The Avignon Papacy. The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 1300–c. 1415. Vol. VI. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-05574-1.

Further reading

- Julian-Jones, Melissa (2020) Murder During the Hundred Year War: The Curious Case of Sir William Cantilupe ISBN 1-5267-5079-1