Human musculoskeletal system

The human musculoskeletal system (also known as the human locomotor system, and previously the activity system) is an organ system that gives humans the ability to move using their muscular and skeletal systems. The musculoskeletal system provides form, support, stability, and movement to the body.

| Musculoskeletal system | |

|---|---|

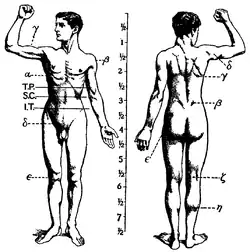

Features of the human activity system from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D009141 |

| TA2 | 351 |

| FMA | 7482 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

It is made up of the bones of the skeleton, muscles, cartilage,[1] tendons, ligaments, joints, and other connective tissue that supports and binds tissues and organs together. The musculoskeletal system's primary functions include supporting the body, allowing motion, and protecting vital organs.[2] The skeletal portion of the system serves as the main storage system for calcium and phosphorus and contains critical components of the hematopoietic system.[3]

This system describes how bones are connected to other bones and muscle fibers via connective tissue such as tendons and ligaments. The bones provide stability to the body. Muscles keep bones in place and also play a role in the movement of bones. To allow motion, different bones are connected by joints. Cartilage prevents the bone ends from rubbing directly onto each other. Muscles contract to move the bone attached at the joint.

There are, however, diseases and disorders that may adversely affect the function and overall effectiveness of the system. These diseases can be difficult to diagnose due to the close relation of the musculoskeletal system to other internal systems. The musculoskeletal system refers to the system having its muscles attached to an internal skeletal system and is necessary for humans to move to a more favorable position. Complex issues and injuries involving the musculoskeletal system are usually handled by a physiatrist (specialist in physical medicine and rehabilitation) or an orthopaedic surgeon.

Subsystems

Skeletal

The skeletal system serves many important functions; it provides the shape and form for the body, support and protection, allows bodily movement, produces blood for the body, and stores minerals.[4] The number of bones in the human skeletal system is a controversial topic. Humans are born with over 300 bones; however, many bones fuse together between birth and maturity. As a result, an average adult skeleton consists of 206 bones. The number of bones varies according to the method used to derive the count. While some consider certain structures to be a single bone with multiple parts, others may see it as a single part with multiple bones.[5] There are five general classifications of bones. These are long bones, short bones, flat bones, irregular bones, and sesamoid bones. The human skeleton is composed of both fused and individual bones supported by ligaments, tendons, muscles and cartilage. It is a complex structure with two distinct divisions; the axial skeleton, which includes the vertebral column, and the appendicular skeleton.[6]

Function

The skeletal system serves as a framework for tissues and organs to attach themselves to. This system acts as a protective structure for vital organs. Major examples of this are the brain being protected by the skull and the lungs being protected by the rib cage.

Located in long bones are two distinctions of bone marrow (yellow and red). The yellow marrow has fatty connective tissue and is found in the marrow cavity. During starvation, the body uses the fat in yellow marrow for energy.[7] The red marrow of some bones is an important site for blood cell production, approximately 2.6 million red blood cells per second in order to replace existing cells that have been destroyed by the liver.[4] Here all erythrocytes, platelets, and most leukocytes form in adults. From the red marrow, erythrocytes, platelets, and leukocytes migrate to the blood to do their special tasks.

Another function of bones is the storage of certain minerals. Calcium and phosphorus are among the main minerals being stored. The importance of this storage "device" helps to regulate mineral balance in the bloodstream. When the fluctuation of minerals is high, these minerals are stored in the bone; when it is low it will be withdrawn from the bone.

Muscular

There are three types of muscles—cardiac, skeletal, and smooth. Smooth muscles are used to control the flow of substances within the lumens of hollow organs, and are not consciously controlled. Skeletal and cardiac muscles have striations that are visible under a microscope due to the components within their cells. Only skeletal and smooth muscles are part of the musculoskeletal system and only the muscles can move the body. Cardiac muscles are found in the heart and are used only to circulate blood; like the smooth muscles, these muscles are not under conscious control. Skeletal muscles are attached to bones and arranged in opposing groups around joints.[8] Muscles are innervated, whereby nervous signals are communicated[9] by nerves, which conduct electrical currents from the central nervous system and cause the muscles to contract.[10]

Contraction initiation

In mammals, when a muscle contracts, a series of reactions occur. Muscle contraction is stimulated by the motor neuron sending a message to the muscles from the somatic nervous system. Depolarization of the motor neuron results in neurotransmitters being released from the nerve terminal. The space between the nerve terminal and the muscle cell is called the neuromuscular junction. These neurotransmitters diffuse across the synapse and bind to specific receptor sites on the cell membrane of the muscle fiber. When enough receptors are stimulated, an action potential is generated and the permeability of the sarcolemma is altered. This process is known as initiation.[11]

Tendons

A tendon is a tough, flexible band of fibrous connective tissue that connects muscles to bones.[12] The extra-cellular connective tissue between muscle fibers binds to tendons at the distal and proximal ends, and the tendon binds to the periosteum of individual bones at the muscle's origin and insertion. As muscles contract, tendons transmit the forces to the relatively rigid bones, pulling on them and causing movement. Tendons can stretch substantially, allowing them to function as springs during locomotion, thereby saving energy.

Joints, ligaments and bursae

Joints are structures that connect individual bones and may allow bones to move against each other to cause movement. There are three divisions of joints, diarthroses which allow extensive mobility between two or more articular heads; amphiarthrosis, which is a joint that allows some movement, and false joints or synarthroses, joints that are immovable, that allow little or no movement and are predominantly fibrous. Synovial joints, joints that are not directly joined, are lubricated by a solution called synovial fluid that is produced by the synovial membranes. This fluid lowers the friction between the articular surfaces and is kept within an articular capsule, binding the joint with its taut tissue.[6]

Ligaments

A ligament is a small band of dense, white, fibrous elastic tissue.[6] Ligaments connect the ends of bones together in order to form a joint. Most ligaments limit dislocation, or prevent certain movements that may cause breaks. Since they are only elastic they increasingly lengthen when under pressure. When this occurs the ligament may be susceptible to break resulting in an unstable joint.

Ligaments may also restrict some actions: movements such as hyper extension and hyper flexion are restricted by ligaments to an extent. Also ligaments prevent certain directional movement.[13]

Bursae

A bursa is a small fluid-filled sac made of white fibrous tissue and lined with synovial membrane. Bursa may also be formed by a synovial membrane that extends outside of the joint capsule.[7] It provides a cushion between bones and tendons or muscles around a joint; bursa are filled with synovial fluid and are found around almost every major joint of the body.

Clinical significance

Because many other body systems, including the vascular, nervous, and integumentary systems, are interrelated, disorders of one of these systems may also affect the musculoskeletal system and complicate the diagnosis of the disorder's origin. Diseases of the musculoskeletal system mostly encompass functional disorders or motion discrepancies; the level of impairment depends specifically on the problem and its severity. In a study of hospitalizations in the United States, the most common inpatient OR procedures in 2012 involved the musculoskeletal system: knee arthroplasty, laminectomy, hip replacement, and spinal fusion.[15]

Articular (of or pertaining to the joints)[16] disorders are the most common. However, also among the diagnoses are: primary muscular diseases, neurologic (related to the medical science that deals with the nervous system and disorders affecting it)[17] deficits, toxins, endocrine abnormalities, metabolic disorders, infectious diseases, blood and vascular disorders, and nutritional imbalances.

Disorders of muscles from another body system can bring about irregularities such as: impairment of ocular motion and control, respiratory dysfunction, and bladder malfunction. Complete paralysis, paresis, or ataxia may be caused by primary muscular dysfunctions of infectious or toxic origin; however, the primary disorder is usually related to the nervous system, with the muscular system acting as the effector organ, an organ capable of responding to a stimulus, especially a nerve impulse.[3]

One understated disorder that begins during pregnancy is pelvic girdle pain. It is complex, multi-factorial, and likely to be also represented by a series of sub-groups driven by pain varying from peripheral or central nervous system,[18] altered laxity/stiffness of muscles,[19] laxity to injury of tendinous/ligamentous structures[20] to maladaptive body mechanics.[18]

References

- Musculoskeletal+System at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Mooar, Pekka (2007). "Muscles". Merck Manual. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- Kahn, Cynthia; Scott Line (2008). Musculoskeletal System Introduction: Introduction. New Jersey, US: Merck & Co., Inc.

- Applegate, Edith; Kent Van De Graaff. "The Skeletal System". Archived from the original on 3 June 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- Engelbert, Phillis; Carol DeKane Nagel (2009). "The Human Body / How Many Bones Are In The Human Body?". U·X·L Science Fact Finder. eNotes.com, Inc. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- Gary, Farr (25 June 2002). "The Musculoskeletal System". Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

- "Skeletal System". 2001. Archived from the original on 25 February 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- Mooar, Pekka (2007). "Muscles". The Merck Manuals Online Medical Library. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- "innervated". Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com, LLC. 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- Bárány, Michael (2002). "SMOOTH MUSCLE". Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- "The Mechanism of Muscle Contraction". Principles of Meat Science (4th Edition). Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

- Jonathan, Cluett (2008). "Tendons". Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- Bridwell, Keith. "Ligaments". Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- Fingar KR, Stocks C, Weiss AJ, Steiner CA (December 2014). "Most Frequent Operating Room Procedures Performed in U.S. Hospitals, 2003–2012". HCUP Statistical Brief #186. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- "articular". Random House Unabridged Dictionary. Random House, Inc. 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- "neurologic". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- Diagnosis and classification of pelvic girdle pain disorders— Part 1: A mechanism based approach within a bio psychosocial framework. Manual Therapy, Volume 12, Issue 2, May 2007, PB. O’Sullivan and DJ Beales.

- Vleeming, Andry; Albert, Hanne B.; Östgaard, Hans Christian; Sturesson, Bengt; Stuge, Britt (June 2008). "European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain". European Spine Journal. 17 (6): 794–819. doi:10.1007/s00586-008-0602-4. PMC 2518998. PMID 18259783.

- Vleeming, Andry; de Vries, Haitze; Mens, Jan; van Wingerden, Jan-Paul (2002). "Possible role of the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament in women with peripartum pelvic pain". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 81 (5): 430–436. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810510.x. ISSN 0001-6349. PMID 12027817. S2CID 18323116.