Islamic marital practices

Muslim marriage and Islamic wedding customs are traditions and practices that relate to wedding ceremonies and marriage rituals prevailing within the Muslim world. Although Islamic marriage customs and relations vary depending on country of origin and government regulations, both Muslim men and women from around the world are guided by Islamic laws and practices specified in the Quran.[1] Islamic marital jurisprudence allows Muslim men to be married to multiple women (a practice known as polygyny).

According to the teachings of the Quran, a married Muslim couple is equated with clothing. Within this context, both husband and wife are each other's protector and comforter, just as real garments “show and conceal” the body of human beings. Thus, they are meant “for one another”.[2] The Quran continues to discuss the matter of marriage and states, "And among His Signs is this, that he created for you mates from among yourselves, that you may dwell in tranquility with them, and He has put love and mercy between your [hearts]…".[3] Marriages within the Muslim community are incredibly important. The purpose of marriage in Islamic culture is to preserve the religion through the creation of a family. The family is meant to be “productive and constructive, helping and encouraging one another to be good and righteous, and competing with one another in good works”.[4]

Choice of partner

In Islam, polygyny is allowed with certain restrictions; polyandry is not. The Quran directly addresses the matter of polygyny in Chapter 4 Verse 3: "...Marry of the women that you please: two, three, or four. But if you feel that you should not be able to deal justly, then only one or what your right hand possesses. That would be more suitable to prevent you from doing injustice."[5] The Prophet accepts the marriage of multiple wives but only if the husband's duties will not falter as a result

Kissing is prohibited before the Nikkah and is highly disliked in public after the wedding.[6]

Although practices of polygamy have declined in practice and acceptance in most parts of the Muslim world (such as Turkey and Tunisia who have completely outlawed it), it is still legal in over 150 countries in Africa, Middle East, and most countries in the third world.[7][8] Since the 20th century and the rise of major feminist movements, polygamous marriages have severely declined. With changing economic conditions, female empowerment, and acceptance of family planning practices, polygamy seems to be severely declining as an acceptable and viable marriage practice within the Muslim world.[9]

In regards to interfaith marriages and partners, the rules for Muslim women are much more restrictive than the rules applied to Muslim men wishing to marry a non-Muslim.[10]

The specific passages of Islamic text that address the issue of interfaith marriage are in Quran 5:5, as well as in Quran 60:10:

This day the good things are allowed to you ... ; and the chaste from among the believing women and the chaste from among those who have been given the Book before you (are lawful for you); when you have given them their dowries, taking (them) in marriage, not fornicating nor taking them for paramours in secret ...[10]

O you who believe! ... ; and hold not to the ties of marriage of unbelieving women, and ask for what you have spent, and let them ask for what they have spent. That is Allah's judgment; He judges between you, and Allah is Knowing, Wise.[10]

Despite the Quranic text that seem to detest interfaith marriage, a growing movement of modern Islamic scholars are beginning to reinterpret and reexamine traditional Shari'a interpretations. While these scholars use "established and approved methodologies" in order to claim new conclusions, they are still met with a considerable amount of opposition from the majority of orthodox Islamic scholars and interpreters.[10]

Islamic dating practices and community programs

In most Islamic societies and communities it is not a common practice for young people to actively seek a partner for themselves by following modern and Western rituals, such as dating. Young Muslim men and women are strongly encouraged to marry as soon as possible, since the family is considered the foundation of Islamic society.[1] According to traditional Islamic law, women and men are not free to date or intermingle, which results in a more drawn-out and deliberate process.[1] The amount of choice and acceptance involved in choosing marriage partners often depends on the class and educational status of the family when it comes to society. In the religion itself though, choosing your partner is allowed and encouraged as long as there are no inappropriate relations, such as dating or being physical.[1] Some important characteristics in choosing a worthy mate are faith and chastity. These traits are pointed out in Quran Chapter 33 Verse 35 "For Muslim men and women, for believing men and women, for true men and women, for men and women who are patient and for men and women who guard their chastity, and for men and women who engage much in Allah's praise, for them has Allah prepared forgiveness and great reward."[1] ‘Forced’ marriages, where consent has not been given by the bride, or is given only under excessive pressure, is considered illegal in all schools of Islamic law. Forced marriage is absolutely and explicitly forbidden.

Since traditional Muslim societies are generally religiously homogeneous, it is much easier for individuals to find socially acceptable partners through traditional methods. Within these communities, families, friends, and services are used to help people find a significant other.[11] However, in non-Muslim countries, like the United States, there is no universal method for matchmaking or finding a spouse. These Muslims must use alternate methods in order to find a partner in a way that closely simulates the traditional process.

Muslims in non-Islamic countries like the United States use Islamic institutions or imams to help them find partners. Islamic institutions like the ISNA (Islamic Society of North America), NOI (Nation of Islam), ICNA (Islamic Circle of North America), and MANA (Muslim Alliance of North America), allow individuals to meet others at annual conventions.[12] The imam is a valued source among these Muslim communities as well. For any individual who values religious piety in a partner and does not have a Muslim social network, the imam is a valuable source of guidance.

The internet also offers new opportunities for Muslim individuals to meet one another. In the past 10 years, Matchmaking sites for Muslims have become an increasingly popular way to meet one's spouse.[13] The website, SingleMuslim.com one of the first matchmaking sites is very successful. Adeem Younis, the founder of the website, designed it in accordance with Islamic principles. Halal sites like SingleMuslim.com and helahel.com ask questions about individuals’ piety including prayer habits, fasting, and if they have made the hajj pilgrimage.[14] Among Islamic theological figures there is some dispute over the validity of these websites; however, these sites continue to be created and avidly used. According to Younis, “Because ‘dating’ is not allowed in Islam, the Internet is an ideal vehicle for a discreet first step in finding a marriage partner."[14] Websites such as, The International Muslim Matrimonial site, broaden the depth of choices for individuals looking for a partner.[15] Individual interests like, hobbies, political views, passions, activities, and family values, are all included to make a user profile. In some societies in both the Islamic world and the West, traditional matchmaking practices do not necessarily include this kind of expression of personal characteristics; therefore, these websites expand individuality while maintaining traditional Islamic ideals of matchmaking.

Diversity of Muslim weddings

Considering that there are over 2 billions Muslims in the Muslim World, there is no single way for all Muslim weddings to be held. There are 49 Muslim majority countries and each contains many regional and cultural differences. Additionally, many Muslims living in the West then mix family traditions with their host countries. [16]

United States

Muslims in the United States come from many backgrounds, but the largest segment are those from South Asia, Arab countries, and more recently from East Africa. When it comes to Muslim weddings the culture they come from heavily influences the kind of rituals that will take place. Similarly American-Muslims e.g. African-Americans, Caucasians, Hispanics and others have elements of both local, and Muslim influence. The central event in all American-Muslim Weddings will be the Nikah. This is the actual wedding ceremony, usually officiated by a Muslim cleric, an Imam. Although a Nikah can be done anywhere including the bride's home or reception hall, it is preferable and usually done in a mosque. [16]

A Muslim Wedding Survey of North American Muslims, revealed among other things the merger of two or more cultures. For example, the two most popular wedding dress colors are red and white. Whereas in traditional Muslim countries marriages have been arranged, in the United States, 57.75% of weddings are through friends, online or people the person has met at work. [17]

China

Prominent Muslims in China, such as generals, followed standard marriage practices in the 20th century, such as using western clothing like white wedding dresses.

Chinese Muslim marriages resemble typical Chinese marriages except traditional Chinese religious rituals are not used.[18]

Indian subcontinent

.JPG.webp)

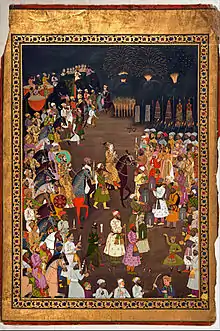

Muslims in the Indian subcontinent normally follow marriage customs that are similar to those practiced by Muslims of the Middle-East, which are based on Islamic convention.[19] These Islamic traditions were first handed down to medieval Indians by propagators of the Islamic religion that involved sultans and Moghul rulers at the time.[20] The blueprint is the same as the Middle-Eastern Nikah,[19] a pattern seen in marriage ceremonies of Sunnis.[20] Traditional Muslim Indian wedding celebrations typically last for three days.[19] Prior to the observance of the wedding ceremony proper, two separate pre-wedding rituals, which involve traditional dancing and singing, occurs in two places: at the groom's house and at the bride's home.[20]

On the eve of the wedding day, a bridal service known as the Mehndi ritual or henna ceremony is held at the bride's home. This ritual is sometimes done two days before the actual wedding day. During this bridal preparation ritual, turmeric paste is placed on the bride's skin for the purpose of improving and brightening her complexion, after which mehndi is applied on the bride's hands and feet by the mehndiwali, a female relative.[19][20]

Now long abandoned, anointing the teeth with a powder called 'missī' in order to blacken them used to be part of Islamic wedding rituals in India.[21]

The Indian Islamic wedding ceremony is also preceded by a marriage procession known as the groom's baraat. From this convoy arrives the groom, who will share a sherbet drink with a brother of his bride at the place of the marriage ceremony. This drinking ritual happens as the sisters of the bride engage in tomfooleries and playfully strike guests using flower-filled cudgels.[19]

The wedding ceremony, known as Nikah,[22] is officiated by the Maulvi, a priest also called Qazi.[19][20] Among the important wedding participants are the Walises, or the fathers of both groom and bride.[19] and the bride's legal representative.[20] It is the bride's father who promises his daughter's hand to the groom, a ritual known as the Kanya-dhan.[20] Also in this formal occasion, particularly in conventional Islamic weddings, when men and women typically have separate seating arrangements. Another common practice are wedding sequences that include the reading of Quranic verses, the groom's proposal and bride's acceptance parts known as the Ijab-e-Qubul[19] or the ijab and qabul;[20] the decision-making of the bride's and groom's families regarding the price of the matrimonial financial endowment known as the Mehar[19] or Mehr (a dower no less than ten dirhams[20]), which will come from the family of bridegroom. Blessings and prayers are then given by older women and other guests to the couple.[19] In return the groom gives salutatory salaam wishes to his blessers, especially to female elders.[20] The bride also usually receives gifts known generally as the burri, which may be in the form of gold jewelries, garments, money, and the like.[20]

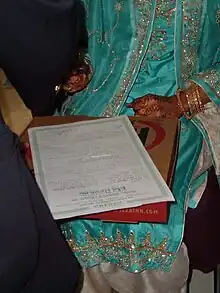

The marriage contract is known as the Nikaahnama, and is signed not only by the couple but also by the Walises and the Maulvi.[19]

After the Nikah, the now married couple joins each other to be seated among gender-segregated attendees.[19] The groom is customarily brought first to the women's area in order for him to be able to present gifts to his wife's sister.[20] Although jointly seated, the bride and the groom can only observe one another via mirrors, and a copy of the Quran is placed in between their assigned seats. With their heads sheltered by a dupatta and while guided by the Maulvi, the couple reads Muslim prayers.[19]

After the wedding ceremony, the bride is brought to the house of her husband, where she is welcomed by her mother-in-law, who holds a copy of the Quran over her head.[19]

The wedding reception hosted by the groom family is known as the Valimah[19] or the Dawat-e-walima.[20]

As per Muslim Personal Law Sharia Application Act of 1937, which is applicable to all Muslims in India (except in the state of Goa), polygamy is legal: a Muslim man may marry a maximum of four women at a time without divorce and with few conditions. Following are the laws applicable to Muslims in India (except in the state of Goa) regarding matters of marriage, succession, Inheritance etc.

- Muslim Personal Law Sharia Application Act,1937

- The Dissolution Of Muslim Marriages Act, 1939

- Muslim Women's Protection of Rights on Divorce Act,1986

Note: Above laws are not applicable in the state of Goa, as state of Goa has Uniform Civil Code i.e. same law irrespective of religion, caste or nationality.

The Malay Archipelago

Malay wedding traditions (Malay: Adat Perkahwinan Melayu; Jawi script: عادة ڤركهوينن ملايو), such as those that occur in Brunei, Singapore, Malaysia, and parts of Indonesia and Thailand, normally include the lamaran or marriage proposal, the betrothal, the determination of the bridal dowry known as the hantaran agreed upon by both the parents’ of the groom and the bride (usually done one year before the solemnization of marriage), delivery of gifts and the dowry (istiadat hantar belanja), the marriage solemnization (upacara akad nikah) at the bride's home or in a mosque, the henna application ritual known as the berinai, the costume changing of the couple known as the tukar pakaian for photography sessions, followed by wedding reception, a feast-meal for guests (pesta pernikahan or resepsi pernikahan) usually took place in the weekend (Saturday or Sunday), and the bersanding or the sitting-in-state ceremony when the couple sit in elaborate pelaminan (wedding throne) at their own home, or in wedding hall during the wedding reception.[23]

Prior to being able to meet his bride, sometimes a mak andam, a “beautician”, or any member of the family of the bride will intercept the groom to delay the joining of the would-be spouses; only after the groom was able to pay a satisfactory “entrance fee” could he finally meet his bride. The wedding ceremony proper is usually held on a weekend, and involves exchanging of gifts, Quranic readings and recitation, and displaying of the couple while within a bridal chamber. While seated at their pelaminan “wedding throne”, the newly-weds are showered with uncooked rice and petals, objects that signify fertility. The guests of the wedding celebration are typically provided by the couple with gifts known as the bunga telur (“egg flower”). The gifted eggs are traditionally eggs dyed with red coloring and are placed inside cups or other suitable containers bottomed with glutinous rice. These eggs also symbolize fertility, a marital wish hoping that the couple will bear many offspring. However, these traditional gifts are now sometimes replaced by non-traditional chocolates, jellies, or soaps.[24]

The marriage contract that binds the marital union is called the Akad Nikah, a verbal agreement sealed by a financial sum known as the mas kahwin, and witnessed by three persons. Unlike in the past when the father of the bride customarily acts as the officiant for the ceremonial union, current-day Muslim weddings are now officiated by the kadhi, a marriage official and Shariat (or) Syariah Court religious officer.[24] In Indonesia Muslim weddings are officiated and led by the penghulu, the official of Kantor Urusan Agama (KUA or Office of Religious Affairs). The Akad Nikah might be performed in the Office of Religious Affairs, or the penghulu is invited to a ceremonial place outside the Religious Affair Office (mosque, bride's house or wedding hall).[25]

The Philippines

Muslim communities in the Philippines include the Tausug and T'boli tribe, a group of people in Jolo, Sulu who practice matrimonial activities based on their own ethnic legislation and the laws of Islam. Their customary and legal matrimony is composed of negotiated arranged marriage (pagpangasawa), marriage through the “game of abduction” (pagsaggau), and elopement (pagdakup).[26] Furthermore, although Tausug men may acquire two wives, bigamous or plural marriages are rare.[26]

Tausug matrimonial customs generally include the negotiation and proclamation of the bridewealth (the ungsud) which is a composition of the “valuables for the offspring” or dalaham pagapusan (in the form of money or an animal that cannot be slaughtered for the marital feast); the "valuables dropped in the ocean" or dalaham hug a tawid, which are intended for the father of the bride; the basingan which is a payment – in the form of antique gold or silver Spanish or American coins – for the transference of kingship rights toward the usba or “male side”; the “payment to the treasury” (sikawin baytal-mal, a payment to officers of the law and wedding officiants); the wedding musicians and performers; wedding feast costs; and the guiding proverb that says a lad should marry by the time he has already personally farmed for a period of three years. This is the reason why young Tausug males and females typically marry a few years after they reached the stage of puberty.[27]

Regular arranged Islamic marriages through negotiation are typically according to parental wishes, although sometimes the son will also suggest a woman of his choice. This is the ideal, esteemed, and considered “most proper” in the legal point of view of Tausug culture, despite of being a time-consuming and costly practice for the groom. If the parents disagree with their son's choice of a woman to marry, he might decide to resort to a marriage by abducting the woman of his choice, run away, run amuck, or choose to become an outlaw. In relation to this type of marriage, another trait that is considered ideal in Tausug marriage is to wed sons and daughters with first or second cousins, due to the absence of difficulty in negotiating and simplification of land inheritance discussions.[26] However, there is also another way of arranging a Tausug marriage, which is through the establishment of maglillah pa maas sing babai or by “surrendering to the lady’s parents”, wherein the lad proclaims his intention while at the house of the parents of the woman of his choice; he will not depart until he receives permission to marry. In other circumstances, the lad offers a sum of money to the parents of the lass; a refusal by the father and mother of the woman would mean paying a fine or doubling the price offered by the negotiating man.[27]

“Abduction-game marriages” are characteristically in accord with the grooms’ requests, and are performed either by force or “legal fiction”.[26] This strategy of marrying a woman is actually a “courtship game” that expresses a Tausug man's masculinity and bravery. Although the woman has the right to refuse marrying her “abductor”, reluctance and refusal does not always endure because the man will resort to seducing the “abductee”. In the case of marriages done through the game of abduction, the bridewealth offered is a gesticulation to appease the woman's parents.[26]

Elopements are normally based on the brides’ desires, which may, at times, are made to resemble a “bride kidnapping” situation (i.e. a marriage through the game of abduction) in order to prevent dishonoring the woman who wished to be eloped.[26] One way of eloping is known to the Tausugs as muuy magbana or the "homecoming to get hold of a husband", wherein a Tausug woman offers herself to the man of her choice or to the parents of the man who she wants to become her spouse. Elopement is also a strategy used by female Tausugs in order to be able to enter into a second marriage, or done by an older unwed lady by seducing a man who is younger than her.[28]

During the engagement period, the man may render service to his bride's parents in the form of performing household chores.[29] After the period of engagement has lapsed, the marital-union ceremony is observed by feastings, delivery of the whole bridewealth, slaughtering of a carabao or a cow, playing gongs and native xylophones, reciting prayers in the Arabic and Tausug languages, symbolic touching by the groom of his bride's forehead, and the couple's emotionless sitting-together ritual. In some instances when a groom is marrying a young bride, the engagement period may last longer until the Tausug lass has reached the right age to marry; or the matrimonial ceremony may proceed – a wedding the Tausug termed as “to marry in a handkerchief” or kawin ha saputangan – because the newly-wed man can live after marriage at the home of his parents-in-law but cannot have marital sex with his wife until she reaches the legal age.[29]

Tausug culture also allows the practice of divorce.[29]

There are also other courtship, marriage, and wedding customs in the Philippines.

United Arab Emirates

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) |

|---|

| Islamic studies |

Generally, wedding ceremonies in the United Arab Emirates traditionally involves scheduling the wedding date, preparation for the bride and groom, and carousing with dancing and singing which takes place one week or less prior to the wedding night. Bridal preparation is done by women by anointing the body of the bride with oil, application of perfumes to the bride's hair, use of creams, feeding the bride with special dishes, washing the bride's hair with amber and jasmine extracts, use of the Arabian Kohl or Arabian eye liner, and decorating the hands and feet with henna (a ritual known as the Laylat Al Henna or “henna night” or "night of henna", and performed a few days before being wed; during this evening, other members of the bride's family and guests also place henna over their own hands). The Emirati bride stays at her dwelling for forty days until the marriage night, only to be visited by her family. Later, the groom offers her items that she will use to create the Addahbia, a dowry which is composed of jewelry, perfumes, and silk, among others.[30]

In Dubai, one of the seven emirates of the UAE, the traditional Bedouin wedding is a ceremonial that echoes the earliest Arab concept of matrimony, which emphasizes that marital union is not simply a joining of a man and a woman but the coming together of two families. Traditionally lasting for seven days, Bedouin marriage preparations and celebration starts with the marriage proposal known as the Al Khoutha, a meeting of the groom's father and bride's father; the purpose of the groom's father is to ask the hand of the bride from the bride's father for marriage; and involves the customary drinking of minty Arab tea. After this, the negotiating families proceed with the Al Akhd, a marriage contract agreement. The bride goes through the ritual of a “bridal shower” known as Laylat Al Henna, the henna tattooing of the bride's hands and feet, a service signifying attractiveness, fortune, and healthiness. The Al Aadaa follows, a groom-teasing rite done by the friends of the bride wherein they ask compensation after embellishing the bride with henna. The ceremonial also involves a family procession towards the bride's home, a re-enactment of a war dance known as Al Ardha, and the Zaahbaah or the displaying of the bride's garments and the gifts she received from her groom's family. In the earliest versions of Bedouin wedding ceremonies, the groom and the bride goes and stays within a tent made of camel hair, and that the bride is not to be viewed in public during the nuptial proceedings. The wedding concludes with the Tarwaah, when the bride rides a camel towards her new home to live with her husband. After a week, the bride will have a reunion with her own family. Customarily, the groom will not be able to join his bride until the formal wedding procedure ended. The only place where they will finally see each other is at their post-wedding dwelling.[31]

Established Bedouin wedding customs also entail the use of hand-embroidered costumes, the dowry, and the bridewealth. Islamic law dictates that the jewelry received by the bride becomes her personal property.[31]

See also

References

- Ponzetti (2003). "International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family". International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family.

- Assadullah, Mir Mohmmed. Weddings in Islam, zawaj.com

- Quran 30: 21

- "The Muslim Woman and Her Husband" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- Quran 4: 3

- Philips, Abu Ameenah Bilal (2005). Polygamy in Islam. International Islamic Publishing House. ISBN 9960-9533-0-0.

- "An Introduction to Polygamy in Islam". IslamReligion.com. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- "WorldFocus". 2009-11-02. Archived from the original on January 23, 2010.

- Historical Dictionaries of Women in the World, 221-22, Ghada Talhami 2013

- Leeman (2009). "Interfaith Marriage in Islam: An Examination of the Legal Theory Behind the Traditional and Reformist Positions". Interfaith Marriage in Islam: An Examination of the Legal Theory Behind the Traditional and Reformist Positions.

- Aziz, Taimoor; Mbaye Lo (Fall 2009). "Muslim Marriage Goes Online: The Use of Internet Matchmaking by American Muslims". Journal of Religion and Popular Culture. 21 (3).

- Beavis, Mary Ann; Dunbar, Scott Daniel; Klassen, Chris (2013). "The Journal of Religion and Popular Culture: More than old wine in new bottles". Religion. 43 (3): 421. doi:10.1080/0048721X.2013.801715. S2CID 143807772.

- De Muth, Susan (2011). "Muslim Matrimonial Websites - Halal or Haram?". The Middle East: 60–61.

- De Muth (2011). The Middle East.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "UK Muslim professionals". www.ukmuslimprofessionals.co.uk. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- Muslim Weddings, PerfectMuslimWedding.com

- "Part 3: Results of 2015 Perfect Muslim Wedding and Marriages Survey". www.perfectmuslimwedding.com. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- Andreas Graeser (1975). Zenon von Kition. Walter de Gruyter. p. 368. ISBN 3-11-004673-3. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- Three Days of a Traditional Indian Muslim Wedding, zawaj.com

- Indian Weddings, zawaj.com

- "Zumbroich, Thomas J. (2015) 'The missī-stained finger-tip of the fair': A cultural history of teeth and gum blackening in South Asia. eJournal of Indian Medicine 8(1): 1-32". Retrieved 2015-03-31.

- Allah has made for you your mates for your own nature for Nikah, Marriage

- "Traditional Wedding Ceremonies and Customs in Indonesia - cultural tips for expats in Indonesia". www.expat.or.id. Retrieved 2017-10-24.

- Said, Rozita Mohd. The Malay Wedding, zawaj.com

- "Tarif Nikah: Nol Rupiah di KUA dan Rp 600 Ribu di Luar KUA | Republika Online". Republika Online (in Indonesian). 26 May 2014. Retrieved 2017-10-24.

- Philippine Muslim (Tausug) Marriages on Jolo Island, Part One: Courtship, zawaj.com

- Philippine Muslim (Tausug) Marriages on Jolo Island, Part Two: Arranged Marriages, zawaj.com

- Philippine Muslim (Tausug) Marriages on Jolo Island, Part Three: Abduction and Elopement, zawaj.com

- Philippine Muslim (Tausug) Marriages on Jolo Island, Part Four: Weddings and Divorces, zawaj.com

- Weddings In The U.A.E., zawaj.com

- Muslim Bedouin Weddings: a Riot of Color and Music, zawaj.com, April 19, 2001