Afonso I of Kongo

Mvemba a Nzinga, Nzinga Mbemba, Funsu Nzinga Mvemba or Dom Alfonso (c. 1456–1542 or 1543),[1] also known as King Afonso I, was the sixth ruler of the Kingdom of Kongo from the Lukeni kanda dynasty and ruled in the first half of the 16th century. He reigned over the Kongo Empire from 1509 to late 1542 or 1543.

| Mvemba a Nzinga of Kongo | |

|---|---|

| Mwene Kongo | |

| |

| Reign | 1509 to late 1542 or 1543 |

| Predecessor | João I |

| Successor | Pedro I |

| Born | Mvemba a Nzinga Mbanza-Kongo |

| Died | Mbanza-Kongo |

| Dynasty | Lukeni kanda |

| Father | Nzinga a Nkuwu |

| Mother | Nzinga a Nzala or Yala |

Biography

Pre-reign career

Born Mvemba a Nzinga, he was the son of Manikongo (Mwene Kongo) (king) Nzinga a Nkuwu, the fifth king of the Kongo dynasty.

At the time of the first arrival of the Portuguese to the Kingdom of the Kongo's capital of M'banza-Kongo in 1491, Mvemba a Nzinga was in his thirties and was the ruler of Nsundi province in the northeast, and the likely heir to the throne. He took the name Afonso when he was baptized after his father decided to convert to Christianity. He studied with Portuguese priests and advisers for ten years in the kingdom's capital. Letters written by priests to the king of Portugal paint Afonso as an enthusiastic and scholarly convert to Christianity. Around 1495, the Manikongo denounced Christianity, and Afonso welcomed the priests into the capital of his Nsundi province. To the displeasure of many in the realm, he ordered the destruction of traditional art objects that might offend Portuguese sensibilities.

Rise to power

In 1506 King João I of Kongo (the name Nzinga a Nakuru took upon his conversion) died, and potential rivals lined up to take over the kingdom. Kongo was an elective rather than a hereditary monarchy, so Afonso was not guaranteed the throne. Afonso was assisted in his attempt to become king by his mother, who kept news of João's death a secret, and arranged for Afonso to return to the capital city of Mbanza Kongo and gather his followers. When the death of the king was finally announced, Afonso was already in the city.

"A final piece of incidental information concerns the presence of Christianity. Although it is sometimes believed that Christianity did not survive the reign of Afonso, an impression was created in part by the slanderous correspondence of Jesuit missionaries and São Tomé officials written against Diogo, in fact, all the actors appear as fairly solid Christians. For example, when he first broke the plan to Afonso, Dom Pedro asked him first to swear on a holy Bible to keep it a secret (gol. 2v). Furthermore, Diogo apparently observed the right of Christian asylum in a church enough to allow Pedro to operate from a church for years after his desposition, even though officials from that same church were important witnesses in the trial and obviously played a significant part in revealing the plot (fols. 2r-2v; 4v; 5r-5v; 8). Both Pedro and Diogo respected the decisions of the Pope in the question of succession, and both thought to obtain the requisite bulls recognizing them as rulers of Kongo."

Battle of Mbanza Kongo

The strongest opposition to Afonso's claim came from his half brother Mpanzu a Kitima (or Mpanzu a Nzinga). Mpanzu raised an army in the provinces and made plans to march on Mbanza Kongo. Afonso's adherence to Catholicism was seemingly rewarded when he fought traditionalists led by his brother Mpanza for succession to the throne. His victory was attributed to a miracle described by the chronicler Paiva Manso, who said the army of Mpanzu a Kitima, though outnumbering Afonso's, fled in terror at the apparition of Saint James the Great and five heavenly armored horsemen in the sky.[2]

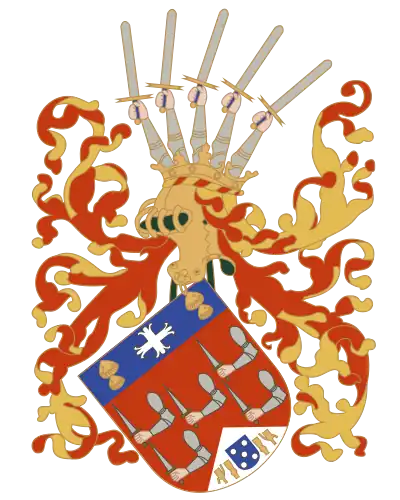

The story, first recounted in a letter that was not survived by Afonso himself,[3] is open to many interpretations including allegory covering up a coup and the forcing out of anti-Catholic elements within the royal house.[4] What is known is that Mpanzu either fell into a sort of punji trap during his army's rout or was executed by Afonso after the battle.[3] The Portuguese are never mentioned as participating in the battle either by the missionaries present in the kingdom or by Afonso in his letters to Portugal's king. Christianity became the royal faith from then on, and the "miracle" was immortalized in Kongo's coat of arms.[5] The coat of arms was in use in Kongo until at least 1860.

Reign

Virtually all that is known about Kongo in the time of Afonso's reign is known from his long series of letters, written in Portuguese, primarily to the kings Manuel I and João III of Portugal. The letters are often very long and give many details about the administration of the country. Many letters complain about the behavior of several Portuguese officials, and these letters have given rise to an interpretation of Afonso's reign as one in which Portuguese interests submerged Afonso's ambitions.

He reigned over the prince Kongo Empire from 1509 to late 1542 or 1543. During this time, Afonso I had an increasingly awkward relationship with Portugal. This relationship came to a head during the latter half of the 1520s when the Kongo slave trade was at its peak, a direct result of Portuguese traders violating the law of Afonso I concerning who could and who could not be sold as a slave. The Portuguese actively subverted Afonso I by going through his vassals. Afonso I expressed a great deal of irritation with the Portuguese in a letter he wrote in 1514. In this letter Afonso I openly stated he would like to have full control of the Kongo-Portuguese slave trade. The Portuguese did not approve of this measure and the situation progressively got worse. The slave trade continued unabated until it was resolved in 1526. Afonso I in 1526 created a commission to investigate the origin of any individual who was to be sold as a slave. This helped put an end to the illegal slave trade occurring in the Kongo.

Although Afonso was outspokenly opposed to slavery and initially fought the Portuguese demand for human beings, he eventually relented in order to sustain the economy of the Kongo. Initially, Afonso sent war captives and criminals to be sold as slaves to the Portuguese. Eventually, Portuguese demand for slaves exceeded the country's potential supply, prompting them to search for slaves in neighboring regions.[6]

Afonso let this situation continue for as long as it did in an attempt to not be overtly rude to the Portuguese, as he had actively required their help to solve various conflicts within his Kingdom. Afonso I also had been attempting to resolve the situation diplomatically through letters to the Vatican as well as to Portugal. The responses told him that they had little intention of altering the actions of the Portuguese traders. The Portuguese regarded the slave trade as nothing more than typical commerce. This is why the commission was established. The Portuguese showed clear disdain for the condition of the slave economy of the Kongo and made a failed attempt to assassinate Afonso I in 1540.

During his reign Afonso I leveraged other desirable resources to consolidate his power and to maintain the status quo with Portugal, mainly gold, iron, and copper. These resources were the bargaining chips that allowed Afonso I to negotiate with the Portuguese, but also to insulate himself from them as well to a lesser extent.

In Adam Hochschild's 1998 book King Leopold's Ghost, Hochschild characterizes Afonso as a "selective modernizer" because he welcomed Europe a scientific innovation and the church but refused to adopt Portugal's legal code and sell land to prospectors.[7] In fact, Afonso ridiculed the Ordenações Manuelinas (new Portuguese law code) when he read it in 1516, asking the Portuguese emissary de Castro, "What is the punishment, Castro, for putting one's feet on the ground?" No contemporary record mentions anything about land sales, indeed land in Kongo was never sold to anyone.

Conversion of Kongo

Afonso is best known for his vigorous attempt to convert Kongo to a Catholic country, by establishing the Roman Catholic Church in Kongo, providing for its financing from tax revenues, and creating schools. By 1516 there were over 1000 students in the royal school, and other schools were located in the provinces, eventually resulting in the development of a fully literate noble class (schools were not built for ordinary people). Afonso also sought to develop an appropriate theology to merge the religious traditions of his own country with that of Christianity. He studied theological textbooks, falling asleep over them, according to Rui de Aguiar (the Portuguese royal chaplain who was sent to assist him). To aid in this task, Afonso sent many of his children and nobles to Europe to study, including his son Henrique Kinu a Mvemba, who was elevated to the status of bishop in 1518. He was given the bishopric of Utica (in North Africa) by the Vatican, but actually served in Kongo from his return there in the early 1520s until his death in 1531.

Afonso's efforts to introduce Portuguese culture to the Kongo was reflected in several ways. The Kongolese aristocracy adopted Portuguese names, titles, coats of arms, and styles of dress. Youths were sent from elite families to Europe for education. Christian festivals were observed, churches were erected, and craftsmen made Christian artifacts that were found by missionaries in the 19th century.[8]

Significantly, religious brotherhoods (organizations) were founded in imitation of Portuguese practices. The ranks of brotherhoods would be called by different European titles, with the elected leader of each brotherhood having the title "king." To celebrate Pentecost, these brotherhoods organized processions that had the multiple motives of celebrating Saints, the brotherhoods themselves, and allowed the brotherhoods an opportunity to collect money.[8] These celebrations lived on in slave communities in Albany, NY as Pinkster.

The precise motivation behind Afonso's campaign of conversion is unclear. "Scholars continue to dispute the authenticity of Kongolese Christian faith and the degree to which the adoption of a new faith was motivated by political and economic realities."[9] Although the degree to which Afonso was purely spiritually motivated is uncertain, it is clear that the Kongo's conversion resulted in the far-reaching European engagement with both political and religious leaders who supported and legitimized the Christian kingdom throughout the rest of its history.

Slave trade

"The Portuguese became an increasing problem within the kingdom. Many of the architects, doctors and pharmacists turned to commerce rather than practicing their professions. They ignored the laws of the Kongo, and in 1510 Afonso had to ask Portugal for a special representative with authority over his countrymen. The Portuguese were able to benefit from their position more than Kongo; Lisbon was unable to control its settlers in Kongo or São Tomé. In the end there was a massive involvement of Portuguese in Kongolese affairs and a breakdown of authority in Kongo."[10] [11][12][13]

In 1526 Afonso wrote a series of letters condemning the violent behavior of the Portuguese in his country and the establishment of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. At one point he accused them of assisting brigands in his own country and illegally purchasing free people as slaves. He also threatened to close the trade altogether. However, in the end, Afonso established an examination committee to determine the legality of all enslaved persons presented for sale.

Afonso was a determined soldier and extended Kongo's effective control to the south. His letter of 5 October 1514 reveals the connections between Afonso's men, Portuguese mercenaries in Kongo's service and the capture and sale of slaves by his forces, many of which he retained in his own service.

In 1526 Afonso wrote two letters concerning the slave trade to the king of Portugal, decrying the rapid destabilization of his kingdom as the Portuguese slave traders intensified their efforts.

In one of his letters he writes:

Each day the traders are kidnapping our people – children of this country, sons of our nobles and vassals, even people of our own family. This corruption and depravity are so widespread that our land is entirely depopulated. We need in this kingdom only priests and schoolteachers, and no merchandise, unless it is wine and flour for Mass. It is our wish that this Kingdom not be a place for the trade or transport of slaves. Many of our subjects eagerly lust after Portuguese merchandise that your subjects have brought into our domains. To satisfy this inordinate appetite, they seize many of our black free subjects. ... They sell them. After having taken these prisoners [to the coast] secretly or at night. ... As soon as the captives are in the hands of white men they are branded with a red-hot iron.[7]

Afonso believed that the slave trade should be subject to Kongo law. When he suspected the Portuguese of receiving illegally enslaved persons to sell, he wrote into King João III in 1526 imploring him to put a stop to the practice.[14]

Afonso was also concerned about the depopulation of his kingdom through the exportation of his own citizens. The king of Portugal responded to Afonso's concerns, writing that because the Kongo purchases their slaves from outside of the kingdom and converts them to Christianity and then intermarries them, the kingdom probably maintains a high population and must not even notice the missing subjects. To lessen Afonso's concerns, the king suggested sending two men to a designated point in the city to monitor who is being traded and who could object to any sale involving a subject of Afonso's kingdom. The king of Portugal then wrote that if he were to cease the slave trade from the inside of the Kongo, he would still require provisions from Afonso, such as wheat and wine.[15]

Death

Toward the end of his life, Afonso's children and grandchildren began maneuvering for the succession, and in 1540 plotters that included Portuguese residents in the country made an unsuccessful attempt on his life. He died toward the end of 1542 or perhaps at the very beginning of 1543, leaving his son Pedro to succeed him. Although his son was soon overthrown by his grandson Diogo (in 1545) and had to take refuge in a church, the grandchildren and later descendants of three of his daughters provided many later kings.

Popular culture

- Afonso I (referred to as Mvemba a Nzinga) leads the Kongolese civilization in the 2016 4X video game Civilization VI.

Bibliography

- Afonso's letters are all published, along with most of the documents relating to his reign in:

- António Brásio, Monumenta Missionaria Africana (1st series, 15 volumes, Lisbon: Agência Geral do Ultramar, 1952–88), vols. 1, 2 and 4.

- While a separate publication of just his letters and allied documents (in French translation) is in Louis Jadin and Mirelle Dicorati, La correspondence du roi Afonso I de Congo (Brussels, 1978).

- McKnight, Kathryn Joy, and Leo J. Garofalo. "Afro-Latino Voices: Narratives from the Early Modern Ibero-Atlantic World, 1550-1812."

References

- The Encyclopedia of African-American Heritage by Susan Altman, Chapter M, page 181

- George Balandier "Daily Life in the Kingdom of the Kongo" (1968), p. 49

- Akyeampong, Emmanuel K. and Henry Louis Gates Jr "Dictionary of African Biography" (2011), p. 104

- George Balandier "Daily Life in the Kingdom of the Kongo" (1968), p. 50

- Linda Heywood " Central Africans and Cultural Transformations in the American Diaspora" (2002), p. 84

- "Alfonso I [King] (?-1543) •". 10 June 2009.

- King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Houghton Mifflin Books. 1998. ISBN 0-618-00190-5. Archived from the original on 2012-12-08. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the Formation of the Americas 1585-1660 by Linda M. Haywood and John Thorton and The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo by Cecile Fromont

- African Christianity in the Kongo. | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Mark R. Lipchitz and R. Kent Rasmussen, Dictionary of African Historical Biography, University of California Press, 1989

- "Afonso I (A)".

- Thornton, John (1981). "Early Kongo-Portuguese Relations: A New Interpretation". History in Africa. 8: 183–204. doi:10.2307/3171515. JSTOR 3171515. S2CID 162201034.

- Norbert C. Brockman, An African Biographical Dictionary, ABC-CLIO, 1994

- African Political Ethics and the Slave Trade Archived March 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Newitt, M. D. D. "8." The Portuguese in West Africa, 1415-1670: A Documentary History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. 151–153. Print.