Mycena manipularis

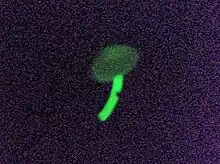

Mycena manipularis is a species of agaric fungus in the family Mycenaceae. Found in Australasia, Malaysia, and the Pacific islands, the mycelium and fruit bodies of the fungus grow in forests[2] and can be bioluminescent.[3] The fruiting bodies also display a variety of morphologies that have no current genetic attributions.[4] References to Mycena manipularis can be found in Japanese folklore[5] and Indonesian food culture.[6]

| Mycena manipularis | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Agaricales |

| Family: | Mycenaceae |

| Genus: | Mycena |

| Species: | M. manipularis |

| Binomial name | |

| Mycena manipularis | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Favolus manipularis Berk. (1854) | |

Appearance

Mycena manipularis is a macrofungus, so it disperses its spores using fruiting bodies.[7] Fruiting bodies are typically clustered together and have similar morphologies. Differences in morphology are generally seen between different clusters.[4] The clustered fruiting bodies have few, if any, distinct differences. The observed morphological variants have not been attributed to any genetic variations.

Pileus (Cap)

The shape of the pileus in Mycena manipularis displays quite a bit of variation with cone-shaped, flattened, umbonate, depressed, and convex caps being observed.[4][8] The underside of the pileus has pores, rather than gills, where spores are grown and dispersed.[7]

Size

The size of the fungus's pileus ranges from about half-a-centimeter to about six centimeters in diameter.[4] The stipes (stalk) size ranges from two to seven centimeters long.[4]

Coloration

The coloration of Mycena manipularis changes depending on its maturation state. At maturity, the fruiting bodies have white or beige coloration.[4] During maturation, however, the fruiting body - or basidiomata - can also have brown or pink coloration.[4] The visibility of any brown or pink coloration decreases as the fruiting body matures, giving way to the more known white and beige appearance.[4]

Bioluminescence

The bioluminescence of Mycena manipularis is not uniform, with non-luminescent or weakly luminescent strains being reported on Okinawa Island[5] and in Vietnam.[4] This variation, currently, does not have any correlation to the observed morphological variants or to genetic differences. Although, it has been posited that these variations could be attributed to environmental changes.[4] The known variations of its bioluminescence include having the pileus- the whole cap or just the porous underside, stipe, the entire fruiting body, or none of the fruiting body displaying bioluminescence.[4]

When bioluminescence is observed, the fruiting body emits typically 595 photons[9] of green light[10] - making it visible to the human eye.

Habitat

Mycena manipularis populations are found in tropical regions of Asia, Australia and the Pacific Islands. Fruit body clusters are typically found in forests[11] on rotted or rotting wood.[4][2][6]

Cultural References

Japan

Referred to as "reticulated luminous mushroom" or Ami-hikari-také in Japan,[5] Mycena manipularis has integrated itself into Japanese folklore. Fungal bioluminescence, specifically in the post-Edo period, was considered unsettling or "eerie" because people thought that it was caused by Yōkai - supernatural creatures.[5] The bioluminescence displayed by fungi was referred to as Mino-bi - which is translated to raincoat fire. This term was associated with the fungi that grew on rotting wood and straw raincoats.[5]

Indonesia

"Kalut gadong putih" is the local name for Mycena manipularis and it is typically gathered by local tribes and sold at market as a nutrient dense food source.[6]

Endangerment

Currently, Mycena manipularis is considered endangered in the Chiba Prefecture of Japan. But, in the Miyazaki Prefecture, it has been listed as "near threatened".[5]

See also

References

- "Mycena manipularis (Berk.) Sacc. 1887". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- Kim, Nam Kyu; Lee, Jin Heung; Jo, Jong Won; Lee, Jong Kyu (February 2017). "A Checklist of Mushrooms of Cambodia" (PDF). Journal of Forest and Environmental Science. 33 (1): 49–65.

- Desjardin DE, Oliveira AG, Stevani CV (2008). "Fungi bioluminescence revisited". Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences. 7 (2): 170–82. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1033.2156. doi:10.1039/b713328f. PMID 18264584.

- Vydryakova, Galina A.; Morozova, Olga V.; Redhead, Scott A.; Bisset, John (April 4, 2014). "Observations on morphologic and genetic diversity in Filoboletus manipularis (Fungi: Mycenaceae) in southern Viet Nam". Mycology. 5 (2): 81–97 – via National Library of Medicine.

- Oba, Yuichi; Hosaka, Kentaro (May 26, 2023). "The Luminous Fungi of Japan". New Perspectives on Fungal Bioluminescence. 9 (6): 615 – via MDPI.

- Putra, Ivan Permana; Nurdebyandaru, Nicho; Amelya, Mega Putri; Hermawan, Rudy (December 2, 2022). "Review: Current Checklist of Local Names and Utilization Information of Indonesian Wild Mushrooms". Journal of Tropical Biodiversity and Biotechnology. 7 (3): 1–14.

- Volk, Tom (January 2009). "Filoboletus manipularis, a poroid mushroom from the tropics". botit.botany.wisc.edu. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- Nimalrathna, Thilina; Nakamura, Akihiro; Tibpromma, Saowaluck; Galappaththi, Mahesh; Xu, Jianchu; Mortimer, Peter E.; Karunarathna, Samantha C. (February 2022). "The case of the missing mushroom: a novel bioluminescent species discovered within Favolaschia in southwestern China" (PDF). Phytotaxa. 529 (3): 244–256 – via ResearchGate.

- Terashima, Yoshie; Neda, Hitoshi; Hiroi, Masaru (2017). "Luminescent intensity of cultured mycelia of eight basidiomycetous fungi from Japan". Mushroom Science and Biotechnology. 24 (4): 176–181 – via J-Stage.

- Perry, Brian (Spring 2008). Griffeth, K. (ed.). "On the Trail of E.J.H Corner - Collecting Mycenoid Fungi in Malaysia" (PDF). Newsletter of the Friends of the Farlow. No. 51. pp. 1–12. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- Sivinski, John M. (September 1998). "Phototrophism, Bioluminescence, and the Diptera". Florida Entomologist. 81 (3): 282–292 – via JSTOR.