Eastern small-footed myotis

The eastern small-footed bat (Myotis leibii) is a species of vesper bat. It can be found in southern Ontario and Quebec in Canada and in mountainous portions of the eastern United States from New England to northern Georgia, and westward to northern Arkansas.[1] It is among the smallest bats in eastern North America[2] and is known for its small feet and black face-mask. Until recently, all North American small-footed Myotis were considered to be "Myotis leibii". The western population is now considered to be a separate species, Myotis ciliolabrum. The Eastern small-footed bat is rare throughout its range, although the species may be locally abundant where suitable habitat exists.[3] Studies suggest white-nose syndrome has caused declines in their populations.[4][5][6] However, most occurrences of this species have only been counted within the past decade or two and are not revisited regularly, making their population status difficult to assess. Additionally, most bat populations in the Eastern U.S. have been monitored using surveys conducted in caves and mines in the winter, but Eastern small-footed bats hibernate in places that make them unlikely to be encountered during these surveys.[3][7] Perhaps as a result, the numbers of Eastern small-footed bats counted in winter tend to be low and they are relatively variable compared to other species of bats. Many biologists believe the species is stable, having declined little in recent times, but that it is vulnerable due to its relatively restricted geographic range and habitat needs.

| Eastern small-footed bat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Vespertilionidae |

| Genus: | Myotis |

| Species: | M. leibii |

| Binomial name | |

| Myotis leibii Audubon & Bachman, 1842 | |

| |

Description

The eastern small footed bat is between 65 and 95 millimeters in length, has a wingspan of 210 to 250 millimeters, and weighs between 4 and 8 grams (with 4.0-5.25 grams being typical).[8] The bat got its name from its abnormally small hind feet, which are only 7 to 8 millimeters long.[7] A defining characteristic of this bat is its appearance of having a dark facial "mask", created by nearly black ears and muzzle.[7] In most individuals, the ears, wings and interfemoral membrane, (the membrane between the legs and tail) are dark and contrast starkly with the lighter colored fur on the rest of the body.[9] The fur on the dorsal side of their body is dark at the roots, and fades to a light brown at the tips, which gives the bats a signature shiny, chestnut-brown appearance. Like all bats, the eastern small-footed bat has a patagium that connects the body to the forelimbs and tail, aiding in flight. Their head is relatively flat and short, with a forehead that slopes gradually away from the rostrum, a feature that is unique to other individuals in the Myotis species.[7] They have erect ears, which are broad at the base and a short flat nose. Like other Myotis, they have a pointed tragus. They also have a distinctly keeled calcar (cartilagenous rod on the hind legs to support the interfemoral membrane). Their forearm length, which is less than 34 mm, can be used to distinguish them from all other Myotis in Eastern North America. Tail is between 25-45 millimeters in length and protrudes past their interfemoral membrane, and they have a dental formula of 2/3, 1/1, 3/3, 3/3.[7] Eastern small-footed bats are most likely to be confused with the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus), especially in individuals where the face-mask is less apparent; however, forearm size less than 34mm and presence of a keeled calcar are considered diagnostic.

Range and distribution

The range of this species includes Northern Arkansas and southern Missouri, East to the Appalachian Mountains and Ohio River Basin, South into northern Georgia, and North into New England, southern Ontario and Quebec.[10] Distribution is spotty within their entire range, and they are considered to be uncommon. These bats are mostly associated with rock formations in deciduous or coniferous forests. Most observations have been from mountainous areas from 240–1125 meters in elevation, where exposed rock formations are more common. However, the species has also been observed at lower elevation rocky sites.[11] During the spring, summer, and autumn they predominantly roost at emergent rock-outcrops such as cliffs, bluffs, shale barrens, and talus slopes, but also man-made structures, including buildings, joints between segments of cement guard rails, turnpike tunnels, road-cuts, and rip-rap covered dams. The largest populations of Myotis leibii have been found in New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Virginia. (red list) The total count of individuals across all known hibernacula is only 3,000, with roughly 60% of the total number from just two sites in New York.[12] Unfortunately, 90% of their habitat is on private land, which makes it difficult to protect them.[12]

Diet

Eastern small-footed bats are believed to feed primarily on flying insects such as beetles, moths, and flies[13][14][15] and are capable of filling their stomachs within an hour of eating.[16] They are nighttime foragers and usually forage in and along wooded areas at and below canopy height, over streams and ponds, and along cliffs. Moths compose nearly half of their diet, and they forage primarily on soft-bodied prey.[17][14] It is believed that the avoidance of hard prey is due to their small, delicate skulls. The food habits of eastern small-footed bats are similar to those of the closely related California Myotis (M. californicus) and western small-footed bat (M. ciliolabrum), as well as other North American Myotis (e.g., little brown bat, (M. lucifugus), and northern bat, (M. septentrionalis).[18][15]

Hibernation

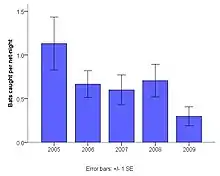

The eastern small-footed bat is most often detected during hibernation, and has been counted at approximately 125 caves and mines.[19] They are one of the last species to enter hibernation in the fall and the first to leave in the spring, with a hibernation period lasting from late November to early April. They have been found in relatively cold caves and mines and can tolerate lower temperatures than other bat species (Whitaker and Hamilton 1998). Unlike most other bat species, they often hibernate in caves and mines that are relatively short (150m) and they are most often found hibernating near the entrance where temperatures sometimes dip below zero and the humidity is low (Barbour and Davis 1969; Merritt 1987; Harvey 1992). Such locations may put them at a greater risk of white nose syndrome, although the species appears to have been less impacted by the disease than some others. Estimates from winter cave and mine surveys suggest the disease caused a 12% decrease in their overall population between 2006 and 2011, which is lower mortality than other species of Myotis experienced at the same sites.[20] Other aspects of their biology make them difficult to count, but also probably offer some protection from WNS. For example, they tend to hibernate individually or in groups of less than 50, and often in small crevices.[16] Bat biologists have speculated that the species also may hibernate outside of caves and mines. Observations of eastern small-footed bats in western Virginia roosting in crevices along sandstone cliff faces in winter support this idea.[21]

Spring and summer roosting

.jpg.webp)

There is little published information about the spring and summer roosting locations of eastern small-footed bats. The first study into the summer roosting habits was only done in 2011 so information is scarce. This study discovered that these bats most commonly use ground level rock roosts in talus slopes, rock fields and vertical cliff faces for their summer roosts.[22] On average they change their roosts every 1.1 days, males travel about 41 meters between consecutive roosts and females around 67 meters. They also found that females roosting sites were closer to ephemeral water sources than male's roosts. Females who have young require roost sites that receive a lot of sunlight in order to keep the pups warm while the mother is away from the roost.[23] Summer roosting habitats were previously considered difficult to find, but several recent studies have shown that the species is relatively easy to locate if survey efforts are focused near appropriate rocky habitats.[3][11][24]

Mating and reproduction

As with many other species of bats, the eastern small-footed bat usually has only one offspring a year, although a few instances of twins have been noted. This k-selected reproductive strategy means that their populations are not capable of withstanding high mortality rates, making them particularly vulnerable to sudden population declines. Mating most often occurs in autumn and the female stores the male's sperm throughout hibernation in the winter. Fertilization occurs in the spring once the females are active again, and gestation occurs between 50–60 days with young being born in late May and early June.[3] Mating has also been noted to occur throughout the hibernation period, if individuals are awake. During the time of breeding, large number of bats come together in a behavior commonly known as "swarming." All bats of this genus are polyandrous, meaning they mate with multiple partners throughout the mating period. This mating behavior allows them to increase the likelihood of copulation, and therefore increase their reproductive success.

Male bats initiate copulation by mounting the female and tilting her hear back 90 degrees. The male then secures his position by biting and pulling back on the hairs at the base of the female's skull. The male then uses his thumbs to further stabilize his position and enters the female under her interfemoral membrane. Both individuals have been noted to be very quiet during copulation. Once the process is over the male dismounts the female and flies away to find another mate.

Newborn bats (called "pups") weight 20–35% of their mother's body weight and are completely dependent on their mother.[10] The young's large body size is believed to lead to high-energy expenditure from the mother, which is what limits her to only having one offspring a year.[23] Adult males and females may use the same rock outcrops, but as is typical for other bats in the genus, the sexes typically roost separately from one another. In Virginia, both sexes appear to roost alone or occasionally in pairs, except females begin to congregate into maternity groups around the time pups are born and likely maintain these "maternity colonies" until pups are weaned.[3][24] Size of maternity colonies is not well studied, but they appear to form smaller groups than other bats in the genus.

Threats

The main threat to this species is habitat disturbance, both natural and human caused. They also likely are under threat from white-nose syndrome, pollution (especially water pollution) and human disturbance during hibernation. Very low levels of light, noise and heat are sufficient to wake hibernating bats. Once awake bats begin to expend energy and deplete critical fat reserves needed to survive winter. If disturbances within hibernacula are repeated, bats (especially juveniles) are likely to die. This phenomenon was well documented in other species of bats in eastern North America, such as the Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis) and gray bat (Myotis grisescens).

White-nose syndrome is a fungal infection that attacks bats while they hibernate. In the first 6 years following the discovery of WNS, 7 million bats of 6 different species were estimated to have been killed by the disease. Early estimates of impacts from white-nose syndrome based on bats counted in hibernacula suggested a 12 percent decline in eastern small-footed bat populations.[6] However, changes in capture rates during summer, in West Virginia and New Hampshire, suggested declines from WNS may have been more severe (68-84%) in some regions.[4][5] Due to their dependency on exposed and predominantly non-forested rock outcrops for roosting sites, they may be at risk from "natural" processes such as forest encroachment and establishment of more mesic forest types due to suppression of forest fires. Likewise, the species is likely threatened a host of human activities that impact rocky habitats or the surrounding areas where eastern small-footed bats forage, such as: mining, quarrying, oil and gas drilling and other forms of mineral extraction, logging, highway construction, wind energy and other forms of agricultural, industrial and residential development. However, it is also likely that some of the above activities have created roosting sites by providing exposed rock faces.

Conservation

The eastern small-footed bat is listed as endangered by the IUCN. Many states in the US in which the bat resides have begun listing it as threatened, and have begun conservation efforts in order to improve its numbers. In Canada, eastern small-footed bats are considered endangered in Ontario, and "threatened or vulnerable" in Quebec. The species is not protected under the US Endangered Species Act, but was a former C2 candidate for listing prior to the abolishment of that category by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service in 1996.[25] Some states (e.g. Pennsylvania) have given the species legal protection while others have recognized its apparently low numbers and consider the eastern small-footed bat a species of concern. In the report Species of Special Concern in Pennsylvania,[25] the Pennsylvania Biological Survey assigned Myotis leibii the status of "threatened". Other states, such as Virginia, are currently working to get the eastern small-footed Myotis legal protection. Despite these efforts not many conservation projects have been initiated to help the species. Due to their strange hibernation patterns, and the lack of information regarding their spring and summer roosting sites, meaningful conservation efforts are very difficult. The species will not usually use bat boxes like many other bat species, so construction of bat boxes is not an appropriate action to mitigate against habitat disturbance issues. However, the species is known to roost in man-made rocky habitats such as road cuts and rip-rap embankments, suggesting it should be possible to create roost sites for conservation purposes.

Longevity

The eastern small-footed bat has been recorded living up to the age of 12 years.[8]

See also

References

- Solari, S. (2018). "Myotis leibii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T14172A22055716. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T14172A22055716.en. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- Blasco, J. "Myotis leibii". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- Moosman; Warner; Hendren; Hosler (2015). "Potential for monitoring eastern small-footed bats on talus slopes". Northeastern Naturalist. 22: NENHC–1–NENHC–13. doi:10.1656/045.022.0102. S2CID 86134583.

- Francl, Karen E.; Ford, W. Mark; Sparks, Dale W.; Brack, Virgil (2011-12-30). "Capture and Reproductive Trends in Summer Bat Communities in West Virginia: Assessing the Impact of White-Nose Syndrome". Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management. 3 (1): 33–42. doi:10.3996/062011-JFWM-039. ISSN 1944-687X. S2CID 86432394.

- Moosman; Veilleux; Pelton; Thomas (2013). "Changes in Capture Rates in a Community of Bats in New Hampshire during the Progression of White-nose Syndrome". Northeastern Naturalist. 20 (4): 552–558. doi:10.1656/045.020.0405. S2CID 84927003.

- Turner; Reeder; Coleman (2011). "Changes in Capture Rates in a Community of Bats in New Hampshire during the Progression of White-nose Syndrome". Bat Research News.

- Best, T.; Jennings, J. (1997). "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Federal register notice of a 90-day finding for Eastern small-footed bat and Northern Long-eared bat". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 547: 1–6.

- Linzey, D.; Brecht, C. "Myotis leibii (Audubon and Bachman); Eastern small-footed Bat". Discover Life. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- Chapman, B (2007). "The Land Manager's Guide to Mammals of the South. Durham, NC". The Nature Conservancy. 191: 1–559.

- Best, T.; Jennings, J. (1997). "Myotis leibi" (PDF). Mammalian Species (547): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3504255. JSTOR 3504255.

- Whitby, Scott (2013). "The Discovery of a Reproductive Population of Eastern Small-footed bat, Myotis leibii, in Southern Illinois Using a Novel Survey Method". American Midland Naturalist. 169: 229–233. doi:10.1674/0003-0031-169.1.229.

- Erdle Y., S. Hobson (2001). Current status and conservation strategy for the eastern small footed Myotis (Myotis leibii), Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, National Heritage Technical Report: #00-19.

- Johnson & Gates (2007). "Food Habits of Myotis leibii during Fall Swarming in West Virginia". Northeastern Naturalist. 14 (3): 317–322. doi:10.1656/1092-6194(2007)14[317:fhomld]2.0.co;2. S2CID 85677262.

- Moosman; et al. (2007). "Food Habits of Eastern Small-footed Bats (Myotis leibii) in New Hampshire". American Midland Naturalist. 158 (2): 354–360. doi:10.1674/0003-0031(2007)158[354:fhoesb]2.0.co;2. S2CID 86157856.

- Thomas, Howard (2012). "Foods of bats from five sites in New Hampshire and Massachusetts". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 126: 117–124. doi:10.22621/cfn.v126i2.1326.

- Best, T., J.S. Altenback., J.M. Harvey Eastern small-footed bat. The Tennessee Bat Working Group.

- Freeman, P. W. (1981). "Correspondence of food habits and morphology in insectivorous bats". Journal of Mammalogy. 62 (1): 166–173. doi:10.2307/1380489. JSTOR 1380489. S2CID 12934993.

- Whitaker, J. O.; Masser, C.; Cross, S. P. (1981). "Food habits if Eastern Oregon bats, based on stomach and scat analyses". Northwest Science. 55: 281–292.

- Arryo-Cabrales, J., T.A. Castaneda (2008). Myotis leibii in IUCN red list. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 13.1.

- Salazar, K., M, Matteson (2010). Petition to list the Eastern small-footed bat Myotis leibii and Northern Long eastern bat Myotis septentrionais as threatened of endangered under the Endangered Species Act. The Center for Biological Diversity.

- Moosman, Paul (2017). "Use of rock-crevices in winter by big brown bats and eastern small-footed bats in the Appalachian Ridge and Valley of Virginia". Banisteria. 48: 9–13.

- Johnson, J.S.; Kiser, J.D.; Watrous, K.S.; Peterson, T.S. (2011). "Day-Roosts of Myotis leibii in the Appalachian Ridge and Valley of West Virginia". Northeastern Naturalist. 18 (1): 96–106. doi:10.1656/045.018.0109. S2CID 86639908.

- Johnson, J.; Gates, E. (2008). "Spring migration and roost selection of female Myotis leibii in Maryland". Northeastern Naturalist. 15 (3): 453–460. doi:10.1656/1092-6194-15.3.453. S2CID 86480502.

- Moosman, Paul (2020). "Efficacy of visual surveys for monitoring populations of talus-roosting bats". Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management. 11 (2): 597–608. doi:10.3996/122019-NAF-002.

- Heoways. H., F.J. Brenner (1985). Species of Special Concern in Pennsylvania. Carnegie Museum of Natural History.