Mythical origins of language

There have been many accounts of the origin of language in the world's mythologies and other stories pertaining to the origin of language, the development of language and the reasons behind the diversity in languages today.

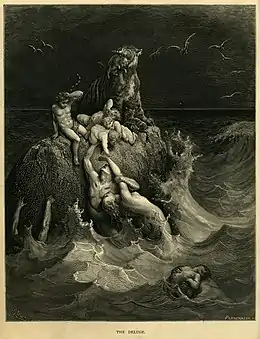

These myths have similarities, recurring themes, and differences, having been passed down through oral tradition. Some myths go further than just storytelling and are religious, with some even having a literal interpretation even today. Recurring themes in the myths of language dispersal are floods and catastrophes. Many stories tell of a great deluge or flood which caused the peoples of the Earth to scatter over the face of the planet. Punishment by a god or gods for perceived wrongdoing on the part of man is another recurring theme.

Myths regarding the origins of language and languages are generally subsumed or footnoted into larger creation myths, although there are differences. Some tales say a creator endowed language from the beginning, others count language among later gifts, or curses.

Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible attributes the origin of language per se to humans, with Adam being asked to name the creatures that God had created.

The Tower of Babel passage from Genesis tells of God punishing humanity for arrogance and disobedience by means of the confusion of tongues.

- And the LORD said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do.

- Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech. (Genesis 11:5-6, KJV translation)

This became the standard account in the European Middle Ages, reflected in medieval literature such as the tale of Fénius Farsaid.

India

Vāc is the Hindu goddess of speech, or "speech personified". As brahman "sacred utterance", she has a cosmological role as the "Mother of the Vedas". She is presented as the consort of Prajapati, who is likewise presented as the origin of the Veda.[1] She became conflated with Sarasvati in later Hindu mythology.

Americas

In common with the mythology of many other civilizations and cultures which tell of a Great Flood, certain Native American tribes tell of a deluge which came over the Earth. After the water subsides, various explanations are given for the new diversity in speech.

Mesoamerica

The Aztecs' story maintains that only a man, Coxcox, and a woman, Xochiquetzal, survive, having floated on a piece of bark. They found themselves on land and begot many children who were at first born unable to speak, but subsequently, upon the arrival of a dove were endowed with language, although each one was given a different speech such that they could not understand one another.[2]

North America

A similar flood is described by the Kaska people from North America, however, like with the story of Babel, the people were now "widely scattered over the world". The narrator of the story adds that this explains the many different centres of population, the many tribes and the many languages, "Before the flood, there was but one centre; for all the people lived together in one country, and spoke one language."[3]

- They did not know where the other people lived, and probably thought themselves the only survivors. Long afterwards, when in their wanderings they met people from another place, they spoke different languages, and could not understand one another.

An Iroquois story tells of the god Taryenyawagon (Holder of the Heavens) guiding his people on a journey and directing them to settle in different places whence their languages changed.[4]

A Salishan myth tells how an argument led to the divergence of languages. Two people were arguing whether the high-pitched humming noise that accompanies ducks in flight is from air passing through the beak or from the flapping of wings. The argument is not settled by the chief, who then calls a council of all the leading people from nearby villages. This council breaks down in argument when nobody can agree, and eventually the dispute leads to a split where some people move far away. Over time they slowly began to speak differently, and eventually other languages were formed.[5]

In the mythology of the Yuki, indigenous people of California, a creator, accompanied by Coyote creates language as he creates the tribes in various localities. He lays sticks which will transform into people upon daybreak.

- Then follows a long journey of the creator, still accompanied by Coyote, in the course of which he makes tribes in different localities, in each case by laying sticks in the house over night, gives them their customs and mode of life, and each their language.[6]

Amazonas, Brazil

The Ticuna people of the Upper Amazon tell that all the peoples were once a single tribe, speaking the same language until two hummingbird eggs were eaten, it is not told by whom. Subsequently, the tribe split into groups and dispersed far and wide.[7]

Europe

The god Hermes brought diversity in speech and along with it separation into nations and discord ensued. Zeus then resigned his position, yielding it to the first king of men, Phoroneus.

In Norse mythology, the faculty of speech is a gift from the third son of Borr, Vé,[8] who gave also hearing and sight.

- When the sons of Borr were walking along the sea-strand, they found two trees, and took up the trees and shaped men of them: the first gave them spirit and life; the second, wit and feeling; the third, form, speech, hearing, and sight.

Africa

The Wasania, a Bantu people of East African origin have a tale that in the beginning, the peoples of the earth knew only one language, but during a severe famine, a madness struck the people, causing them to wander in all directions, jabbering strange words, and this is how different languages came about.

A god who speaks all languages is a theme in African mythology, two examples being Eshu of the Yoruba, a trickster who is a messenger of the gods. Eshu has a parallel in Legba from the Fon people of Benin. Another Yoruba god who speaks all the languages of the world is Orunmila, the god of divination.

In the Ancient Egyptian Religion, Thoth is a semi-mythical being who creates hieroglyphics.[9]

Southeast Asia and Oceania

Polynesia

A group of people on the island of Hao in Polynesia tell a very similar story to the Tower of Babel, speaking of a God who, "in anger chased the builders away, broke down the building, and changed their language, so that they spoke diverse tongues".[10]

Australia

In South Australia, a people of Encounter Bay tell a story of how diversity in language came about from cannibalism:

- In remote time an old woman, named Wurruri lived towards the east and generally walked with a large stick in her hand, to scatter the fires around which others were sleeping, Wurruri at length died. Greatly delighted at this circumstance, they sent messengers in all directions to give notice of her death; men, women and children came, not to lament, but to show their joy. The Raminjerar were the first who fell upon the corpse and began eating the flesh, and immediately began to speak intelligibly. The other tribes to the eastward arriving later, ate the contents of the intestines, which caused them to speak a language slightly different. The northern tribes came last and devoured the intestines and all that remained, and immediately spoke a language differing still more from that of the Raminjerar.[11]

Another group of Australian Aboriginal people, the Kunwinjku, tell of a goddess in dreamtime giving each of her children a language of their own to play with.

Andaman Islands

The traditional beliefs of the indigenous inhabitants of the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal describe language as being given by the god Pūluga to the first man and woman at their union following a great deluge. The language given was called bojig-yâb-, which is the language spoken to this day, according to their belief, by the tribe inhabiting the south and south-eastern portion of middle Andaman. This language is described by the inhabitants as the "mother tongue" from which all other dialects have been made.

Their beliefs hold that even before the death of the first man,

- ... his offspring became so numerous that their home could no longer accommodate them. At Pūluga's bidding they were furnished with all necessary weapons, implements, and fire, and then scattered in pairs all over the country. When this exodus occurred Puluga- provided each party with a distinct dialect.[12]

Thus explaining the diversity of language.

See also

Notes

- "Veda, Prajāpati and Vāc" in Barbara A. Holdrege, 'Veda in the Brahmanas', in: Laurie L. Patton (ed.) Authority, anxiety, and canon: essays in Vedic interpretation, 1994, ISBN 978-0-7914-1937-3.

- Turner, P. and Russell-Coulter, C. (2001) Dictionary of Ancient Deities (Oxford: OUP)

- Teit, J. A. (1917) "Kaska Tales" in Journal of American Folklore, No. 30

- Johnson, E. Legends, Traditions, and Laws of the Iroquois, or Six Nations, and History of the Tuscarora Indians (Access date: 4 June 2009)

- Boas, F. (ed.) (1917) "The Origin of the Different Languages". Folk-Tales of Salishan and Sahaptin Tribes (New York: American Folk-Lore Society)

- Kroeber, A. L. (1907) "Indian Myths of South Central California" in American Archaeology and Ethnology, Vol. 4, No. 4

- Carneiro, R. (2000) "Origin Myths" in California Journal of Science Education

- Vili and Vé

- Littleton, C.Scott (2002). Mythology. The illustrated anthology of world myth & storytelling. London: Duncan Baird Publishers. pp. 24. ISBN 9781903296370.

- Williamson, R. W. (1933) Religious and Cosmic Beliefs of Central Polynesia (Cambridge), vol. I, p. 94.

- Meyer, H. E. A., (1879) "Manners and Customs of the Aborigines of the Encounter Bay Tribe", published in Wood, D., et al., The Native Tribes of South Australia, (Adelaide: E.S. Wigg & Son) (available online here)

- Man, E. H. (1883) "On the Aboriginal Inhabitants of the Andaman Islands. (Part II.)" in The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 12, pp. 117–175.

External links

- Wayne L. Allison - In The Beginning Was The Word: (The Genesis of Language)

- ^ Dickson-White, A. (1995) The Warfare of Science With Theology - Chapter XVII - From Babel To Comparative Philology (Access date: 4 June 2009)

- Velikovsky, I. The Confusion of Languages (Access date: 4 June 2009)

- A Lexicon of Mythical Pantheons of Gods and Heroes (Access date: 4 June 2009)