Dimethylformamide

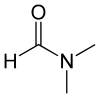

Dimethylformamide is an organic compound with the formula (CH3)2NC(O)H. Commonly abbreviated as DMF (although this initialism is sometimes used for dimethylfuran, or dimethyl fumarate), this colourless liquid is miscible with water and the majority of organic liquids. DMF is a common solvent for chemical reactions. Dimethylformamide is odorless, but technical-grade or degraded samples often have a fishy smell due to impurity of dimethylamine. Dimethylamine degradation impurities can be removed by sparging samples with an inert gas such as argon or by sonicating the samples under reduced pressure. As its name indicates, it is structurally related to formamide, having two methyl groups in the place of the two hydrogens. DMF is a polar (hydrophilic) aprotic solvent with a high boiling point. It facilitates reactions that follow polar mechanisms, such as SN2 reactions.

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

N,N-Dimethylformamide[1] | |||

| Other names | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| 3DMet | |||

| 605365 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.617 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Dimethylformamide | ||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 2265 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C3H7NO | |||

| Molar mass | 73.095 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colourless liquid | ||

| Odor | Odorless, fishy if impure | ||

| Density | 0.948 g/mL | ||

| Melting point | −61 °C (−78 °F; 212 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 153 °C (307 °F; 426 K) | ||

| Miscible | |||

| log P | −0.829 | ||

| Vapor pressure | 516 Pa | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | -0.3 (for the conjugate acid) (H2O)[3] | ||

| UV-vis (λmax) | 270 nm | ||

| Absorbance | 1.00 | ||

Refractive index (nD) |

1.4305 (at 20 °C) | ||

| Viscosity | 0.92 mPa s (at 20 °C) | ||

| Structure | |||

| 3.86 D | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C) |

146.05 J/(K·mol) | ||

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−239.4 ± 1.2 kJ/mol | ||

Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−1.9416 ± 0.0012 MJ/mol | ||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H226, H312, H319, H332, H360 | |||

| P280, P305+P351+P338, P308+P313 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 58 °C (136 °F; 331 K) | ||

| 445 °C (833 °F; 718 K) | |||

| Explosive limits | 2.2–15.2% | ||

Threshold limit value (TLV) |

30 mg/m (TWA) | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose) |

| ||

LC50 (median concentration) |

3092 ppm (mouse, 2 h)[4] | ||

LCLo (lowest published) |

5000 ppm (rat, 6 h)[4] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 10 ppm (30 mg/m3) [skin][5] | ||

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 10 ppm (30 mg/m3) [skin][5] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

500 ppm[5] | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related alkanamides |

|||

Related compounds |

|||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |||

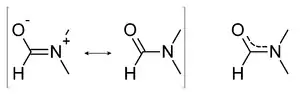

Structure and properties

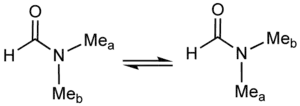

As for most amides, the spectroscopic evidence indicates partial double bond character for the C-N and C-O bonds. Thus, the infrared spectrum shows a C=O stretching frequency at only 1675 cm−1, whereas a ketone would absorb near 1700 cm−1.[6]

DMF is a classic example of a fluxional molecule.[7]

The ambient temperature 1H NMR spectrum shows two methyl signals, indicative of hindered rotation about the (O)C-N bond.[6] At temperatures near 100 °C, the 500 MHz NMR spectrum of this compound shows only one signal for the methyl groups.

DMF is miscible with water.[8] The vapour pressure at 20 °C is 3.5 hPa.[9] A Henry's law constant of 7.47 × 10−5 hPa m3 mol−1 can be deduced from an experimentally determined equilibrium constant at 25 °C.[10] The partition coefficient log POW is measured to −0.85.[11] Since the density of DMF (0.95 g cm−3 at 20 °C[8]) is similar to that of water, significant flotation or stratification in surface waters in case of accidental losses is not expected.

Reactions

DMF is hydrolyzed by strong acids and bases, especially at elevated temperatures. With sodium hydroxide, DMF converts to formate and dimethylamine. DMF undergoes decarbonylation near its boiling point to give dimethylamine. Distillation is therefore conducted under reduced pressure at lower temperatures.[12]

In one of its main uses in organic synthesis, DMF was a reagent in the Vilsmeier–Haack reaction, which is used to formylate aromatic compounds.[13][14] The process involves initial conversion of DMF to a chloroiminium ion, [(CH3)2N=CH(Cl)]+, known as a Vilsmeier reagent,[15] which attacks arenes.

Organolithium compounds and Grignard reagents react with DMF to give aldehydes after hydrolysis in a reaction called Bouveault aldehyde synthesis.[16]

Dimethylformamide forms 1:1 adducts with a variety of Lewis acids such as the soft acid I2, and the hard acid phenol. It is classified as a hard Lewis base and its ECW model base parameters are EB= 2.19 and CB= 1.31.[17] Its relative donor strength toward a series of acids, versus other Lewis bases, can be illustrated by C-B plots.[18][19]

Production

DMF was first prepared in 1893 by the French chemist Albert Verley (8 January 1867 – 27 November 1959), by distilling a mixture of dimethylamine hydrochloride and potassium formate.[20]

DMF is prepared by combining methyl formate and dimethylamine or by reaction of dimethylamine with carbon monoxide.[21]

Although currently impractical, DMF can be prepared from supercritical carbon dioxide using ruthenium-based catalysts.[22]

Applications

The primary use of DMF is as a solvent with low evaporation rate. DMF is used in the production of acrylic fibers and plastics. It is also used as a solvent in peptide coupling for pharmaceuticals, in the development and production of pesticides, and in the manufacture of adhesives, synthetic leathers, fibers, films, and surface coatings.[8]

- It is used as a reagent in the Bouveault aldehyde synthesis[23][24][25] and in the Vilsmeier-Haack reaction,[13][14] another useful method of forming aldehydes.

- It is a common solvent in the Heck reaction.[26]

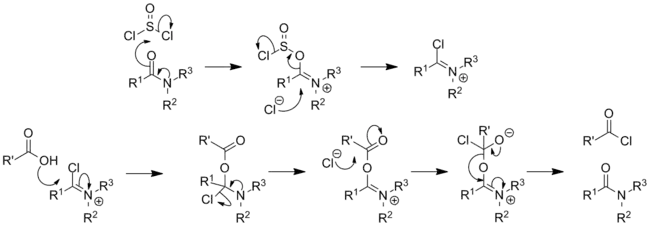

- It is also a common catalyst used in the synthesis of acyl halides, in particular the synthesis of acyl chlorides from carboxylic acids using oxalyl or thionyl chloride. The catalytic mechanism entails reversible formation of an imidoyl chloride (also known as the 'Vilsmeier reagent'):[27][28]

- DMF penetrates most plastics and makes them swell. Because of this property DMF is suitable for solid phase peptide synthesis and as a component of paint strippers.

- DMF is used as a solvent to recover olefins such as 1,3-butadiene via extractive distillation.

- It is also used in the manufacturing of solvent dyes as an important raw material. It is consumed during reaction.

- Pure acetylene gas cannot be compressed and stored without the danger of explosion. Industrial acetylene is safely compressed in the presence of dimethylformamide, which forms a safe, concentrated solution. The casing is also filled with agamassan, which renders it safe to transport and use.

As a cheap and common reagent, DMF has many uses in a research laboratory.

- DMF is effective at separating and suspending carbon nanotubes, and is recommended by the NIST for use in near infrared spectroscopy of such.[29]

- DMF can be utilized as a standard in proton NMR spectroscopy allowing for a quantitative determination of an unknown compound.

- In the synthesis of organometallic compounds, it is used as a source of carbon monoxide ligands.

- DMF is a common solvent used in electrospinning.

- DMF is commonly used in the solvothermal synthesis of metal–organic frameworks.

- DMF-d7 in the presence of a catalytic amount of KOt-Bu under microwave heating is a reagent for deuteration of polyaromatic hydrocarbons.

Safety

Reactions including the use of sodium hydride in DMF as a solvent are somewhat hazardous;[30] exothermic decompositions have been reported at temperatures as low as 26 °C. On a laboratory scale any thermal runaway is (usually) quickly noticed and brought under control with an ice bath and this remains a popular combination of reagents. On a pilot plant scale, on the other hand, several accidents have been reported.[31]

Dimethylformamide vapor exposure has shown reduced alcohol tolerance and skin irritation in some cases.[32]

On the 20 of June 2018, the Danish Environmental Protective Agency published an article about the DMF's use in squishies. The density of the compound in the toy resulted in all squishies being removed from the Danish market. All squishies were recommended to be thrown out as household waste. [33]

Toxicity

The acute LD50 (oral, rats and mice) is 2.2–7.55 g/kg.[8] Hazards of DMF have been examined.[34]

References

- Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. pp. 841, 844. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

The traditional name 'formamide' is retained for HCO-NH2 and is the preferred IUPAC name. Substitution is permitted on the –NH2 group.

- N,N-Dimethylmethanamide, NIST web thermo tables

- "Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB) - N,N-DIMETHYLFORMAMIDE".

- "Dimethylformamide". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0226". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- "Dimethylformamide". Spectral Database for Organic Compounds. Japan: AIST. Retrieved 2012-06-28.

- H. S. Gutowsky; C. H. Holm (1956). "Rate Processes and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectra. II. Hindered Internal Rotation of Amides". J. Chem. Phys. 25 (6): 1228–1234. Bibcode:1956JChPh..25.1228G. doi:10.1063/1.1743184.

- Bipp, H.; Kieczka, H. "Formamides". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a12_001.pub2.

- IPCS (International Programme on Chemical Safety) (1991). Environmental Health Criteria 114 "Dimethylformamide" United Nations Environment Programme, International Labour Organisation, World Health Organization; 1–124.

- Taft, R. W.; Abraham, M. H.; Doherty, R. M.; Kamlet, M. J. (1985). "The molecular properties governing solubilities of organic nonelectrolytes in water". Nature. 313 (6001): 384–386. Bibcode:1985Natur.313..384T. doi:10.1038/313384a0. S2CID 36740734.

- (BASF AG, department of analytical, unpublished data, J-No. 124659/08, 27.11.1987)

- Comins, Daniel L.; Joseph, Sajan P. (2001). "N,N-Dimethylformamide". N,N-Dimethylformamide. Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/047084289x.rd335. ISBN 9780470842898.

- Vilsmeier, Anton; Haack, Albrecht (1927). "Über die Einwirkung von Halogenphosphor auf Alkyl-formanilide. Eine neue Methode zur Darstellung sekundärer und tertiärer p-Alkylamino-benzaldehyde" [On the reaction of phosphorus halides with alkyl formanilides. A new method for the preparation of secondary and tertiary p-alkylamino-benzaldehyde]. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. A/B (in German). 60 (1): 119–122. doi:10.1002/cber.19270600118.

- Meth-Cohn, Otto; Stanforth, Stephen P. (1993). "The Vilsmeier-Haack Reaction". In Trost, Barry M.; Heathcock, Clayton H. (eds.). Additions to CX π-Bonds, Part 2. Comprehensive Organic Synthesis: Selectivity, Strategy and Efficiency in Modern Organic Chemistry. Vol. 2. Elsevier. pp. 777–794. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-052349-1.00049-4. ISBN 9780080405933.

- Jones, Gurnos; Stanforth, Stephen P. (2000). "The Vilsmeier Reaction of Non-Aromatic Compounds". Org. React. 56 (2): 355–686. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or056.02.

- Wang, Zerong (2009). Comprehensive organic name reactions and reagents. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley. pp. 490–492. ISBN 9780471704508.

- Vogel G. C.; Drago, R. S. (1996). "The ECW Model". Journal of Chemical Education. 73 (8): 701–707. Bibcode:1996JChEd..73..701V. doi:10.1021/ed073p701.

- Laurence, C. and Gal, J-F. Lewis Basicity and Affinity Scales, Data and Measurement, (Wiley 2010) pp 50-51 ISBN 978-0-470-74957-9

- Cramer, R. E.; Bopp, T. T. (1977). "Graphical display of the enthalpies of adduct formation for Lewis acids and bases". Journal of Chemical Education. 54: 612–613. doi:10.1021/ed054p612. The plots shown in this paper used older parameters. Improved E&C parameters are listed in ECW model.

- Verley, A. (1893). "Sur la préparation des amides en général" [On the preparation of amides in general]. Bulletin de la Société Chimique de Paris. 3rd series (in French). 9: 690–692. On p. 692, Verley states that DMF is prepared by a procedure analogous to that for the preparation of dimethylacetamide (see p. 691), which would be by distilling dimethylamine hydrochloride and potassium formate.

- Weissermel, K.; Arpe, H.-J. (2003). Industrial Organic Chemistry: Important Raw Materials and Intermediates. Wiley-VCH. pp. 45–46. ISBN 3-527-30578-5.

- Walter Leitner; Philip G. Jessop (1999). Chemical synthesis using supercritical fluids. Wiley-VCH. pp. 408–. ISBN 978-3-527-29605-7. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- Bouveault, Louis (1904). "Modes de formation et de préparation des aldéhydes saturées de la série grasse" [Methods of preparation of saturated aldehydes of the aliphatic series]. Bulletin de la Société Chimique de Paris. 3rd series (in French). 31: 1306–1322.

- Bouveault, Louis (1904). "Nouvelle méthode générale synthétique de préparation des aldéhydes" [Novel general synthetic method for preparing aldehydes]. Bulletin de la Société Chimique de Paris. 3rd series (in French). 31: 1322–1327.

- Li, Jie Jack (2014). "Bouveault aldehyde synthesis". Name Reactions: A Collection of Detailed Mechanisms and Synthetic Applications (5th ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-3-319-03979-4.

- Oestreich, Martin, ed. (2009). The Mizoroki–Heck Reaction. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470716069.

- Clayden, J. (2001). Organic Chemistry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 276–296. ISBN 0-19-850346-6.

- Ansell, M. F. in "The Chemistry of Acyl Halides"; S. Patai, Ed.; John Wiley and Sons: London, 1972; pp 35–68.

- Haddon, R.; Itkis, M. (March 2008). "3. Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy" (pdf). In Freiman, S.; Hooker, S.; Migler; K.; Arepalli, S. (eds.). Publication 960-19 Measurement Issues in Single Wall Carbon Nanotubes. NIST. p. 20. Retrieved 2012-06-28.

- Explosion Hazards of Sodium Hydride in Dimethyl Sulfoxide, N,N-Dimethylformamide, and N,N-Dimethylacetamide Qiang Yang, Min Sheng, James J. Henkelis, Siyu Tu, Eric Wiensch, Honglu Zhang, Yiqun Zhang, Craig Tucker, and David E. Ejeh Organic Process Research & Development 2019 23 (10), 2210-2217 DOI: 10.1021/acs.oprd.9b00276 https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.oprd.9b00276

- UK Chemical Reaction Hazards Forum Archived 2011-10-06 at the Wayback Machine and references cited therein

- Lyle, W. H.; Spence, T. W.; McKinneley, W. M.; Duckers, K. (1979). "Dimethylformamide and alcohol intolerance". British Journal of Industrial Medicine. 36 (1): 63–66. doi:10.1136/oem.36.1.63. PMC 1008494. PMID 444443.

- Magnus Løfstedt. "Skumlegetøj afgiver farlige kemikalier (in English- Squishies giving dangerous chemicals)". Archived from the original on 2021-09-03. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

- Redlich, C.; Beckett, W. S.; Sparer, J.; Barwick, K. W.; Riely, C. A.; Miller, H.; Sigal, S. L.; Shalat, S. L.; Cullen, M. R. (1988). "Liver disease associated with occupational exposure to the solvent dimethylformamide". Annals of Internal Medicine. 108 (5): 680–686. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-108-5-680. PMID 3358569.

External links

- International Chemical Safety Card 0457

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0226". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Concise International Chemical Assessment Document 31: N,N-Dimethylformamide