Sânnicolau Mare

Sânnicolau Mare (Romanian pronunciation: [sɨnnikoˌla.u ˈmare]; Hungarian: Nagyszentmiklós; German: Groß St. Nikolaus; Banat Swabian: Sanniklos;[4] Serbian: Велики Семиклуш, romanized: Veliki Semikluš; Banat Bulgarian: Smikluš) is a town in Timiș County, Romania, and the westernmost in the country. Located in the Banat region, along the borders with Serbia and Hungary, it has a population of just over 10,000.

Sânnicolau Mare | |

|---|---|

| |

Coat of arms | |

Location in Timiș County | |

Sânnicolau Mare Location in Romania | |

| Coordinates: 46°3′49″N 20°36′45″E | |

| Country | Romania |

| County | Timiș |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–2024) | Dănuț Groza[1] (PNL) |

| Area | 133.92 km2 (51.71 sq mi) |

| Population (2021-12-01)[3] | 10,627 |

| • Density | 79/km2 (210/sq mi) |

| Time zone | EET/EEST (UTC+2/+3) |

| Postal code | 305600 |

| Vehicle reg. | TM |

| Website | www |

Geography

Sânnicolau Mare is the westernmost town of Romania and Timiș County, being also the third largest town after Timișoara and Lugoj. It is a border town, having a 6 km (3.7 mi) border with Hungary, on the unregularized course of the Mureș River. It covers an area of 133.92 km2 (51.71 sq mi), 1.55% of the area of Timiș County. It borders Saravale to the east, Tomnatic to the south, Teremia Mare to the southwest, Dudeștii Vechi to the west and Cenad to the northwest.

The town has a number of 112 streets with a length of 60.85 km (37.81 mi), arranged perpendicularly to each other. The length of the town is 4 km (2.5 mi), and the width is 3.2 km (2.0 mi).[2] The houses are arranged according to the alignment of the streets and mostly with the length perpendicular to the axis of the street, being parallel to each other. It is divided into 106 rectangle- (70%), square- (20%) and multiform-shaped (10%) blocks and has nine neighborhoods, built along its historical stages:[5]

- Bujak

- Centru

- Capul Satului

- Comuna Germană

- Kindărești

- Primăverii

- Satul Nou

- Sighet

- Slatina

A note about Romanian Bujak from Sânnicolau Mare and Moldavian Budjak: The Budjak culture of the North-West Black Sea region is considered to be important in the context of the Pit-Grave or Yamnaya culture of the Pontic steppe, dating to 3,600–2,300 BC. In particular, Budjak may have given rise to the Balkan-Carpathian variant of Yamnaya culture.[Ivanova S.V., Balkan-Carpathian variant of the Yamnaya culture-historical region. Российская археология, Number 2, 2014 (in Russian)]

In Classical antiquity, Budjak was inhabited by Tyragetae, Bastarnae, Scythians, and Roxolani. In 6th century BC Ancient Greek colonists established a colony at the mouths of Dnister river, Tyras.[Unknown article. Archived 14 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine Viața Basarabiei. I.6 (June 1932). (in Romanian)] Around 2nd century BC, also a Celt tribe settled at Aliobrix (present day Cartal/Orlovka).

Budjak area, the northern Lower Danube, was described as the "wasteland of the Getae" by the ancient Greek geographer Strabo (1st century BC). In fact, based on recent archaeological research, in this period of time, the area was most likely populated by sedentary farmers; among them were the Dacians and the Daco-Romans. [The nomad peoples, such as the Sarmatians also passed through the area.iculiță, Ion; Sîrbu, Valeriu; Vanchiugov, Vladimir, The Historical Evolution of Budjak in the 1st–4th c. AD. A few observations. ISTROS (Vol. 14/2007)]

Relief

The town lies in the low plain of the Aranca Canal. It is generally flat, only slightly fragmented, as a result of water erosion during the time when Mureș was able to overflow and uneven deposition of alluvial material.

The territory is located in the Mureș Plain, which is a typical form of fluvio-lacustrine subsidence, with shallow valleys with abandoned riverbeds resulting from the regularization of watercourses and drainage, with an altitude between 80–85 m (262–279 ft). The northern part is located in the former meadow of Mureș, and the southern part in the former meadow of the old Aranca stream, today regularized and canalized.

On the territory of the town there are some elevations with southwest–northeast direction, which continue towards Saravale commune. The most important of these hunci (elevations) is located on the former border line between the town and the former commune of Sânnicolau German (now incorporated into the town), south of the Dudeștii Vechi–Tomnatic road, and is called Hunca Farchii. The most important natural resource is geothermal water, which is used in greenhouses, in hemp smelters and in heating homes.[2]

Hydrography

The main collector of the Aranca Plain is the Aranca, which flows into the Tisa. The Aranca Canal is installed on the former riverbeds of the Mureș and has a divagation area before its damming. It springs from the Mureș meadow, from Felnac (where the Mureș dam begins) and flows into the Tisa.

The Aranca Canal crosses Sânnicolau Mare and in the past aimed to drain water from flooded lands, being widened and deepened in 1959 and 1960. On the territory of the town it has a length of 10 km (6.2 mi) and 532 m (1,745 ft), a width ranging from 6–16 m (20–52 ft) and a depth of between 1–3 m (3.3–9.8 ft). The maximum flow is recorded in spring, and the minimum flow in summer.[2]

Climate

Due to its geographical position, Sânnicolau Mare falls within the conditions of temperate continental climate, with the predominance of maritime and continental air masses of eastern origin, to which are added the warm air masses that cross the Mediterranean and some polar cold air masses. Western circulation persists in both the cold and warm periods of the year and is characterized by mild winters with liquid precipitation. Polar circulation is determined by the cyclones in the North Atlantic and is characterized by temperature drops, heavy cloudiness and precipitation in the form of showers, and in winter the snow is accompanied by intense winds. Tropical circulation causes mild winters and significant amounts of precipitation, and in summer an unstable weather with showers and electric discharges.

The average annual temperature is 10.7 °C (51.3 °F). The average seasonal temperatures are as follows: in spring 11 °C or 52 °F (April), in summer 21.9 °C or 71.4 °F (July), in autumn 11.8 °C or 53.2 °F (October) and in winter 1.4 °C or 34.5 °F (January). Average monthly temperatures below 0 °C (32 °F) are recorded only in January (−1.4 °C or 29.5 °F) and February (−0.1 °C or 31.8 °F). The average annual thermal amplitude is 23.3 °C or 41.9 °F (i.e., the temperature difference between January (–1.4 °C) and July (21.9 °C)). The number of frost days is 46–49/year, and the first frost is recorded in mid-October, and the last in mid-April. The number of winter days (maximum temperature < 0 °C) is low due to the influence of warm and humid maritime air. Most winter days are recorded in January. The number of tropical days (maximum temperature > 30 °C or 86 °F) exceeds 35, being characteristic of July and August.[2]

The average annual rainfall is 535.3 mm (21.07 in). During the year, the heaviest rainfall is in June (69.5 mm or 2.74 in), and the lowest is in February (29.1 mm or 1.15 in). By season, the rainfall is distributed as follows: in spring 134.5 mm (5.30 in), in summer 171.2 mm (6.74 in), in autumn 132.8 mm (5.23 in) and in winter 89.8 mm (3.54 in). Winter is usually poorer in snow, with the soil being covered in snow for an average of 30 days/year, of which 15 days are in January.[2]

The prevailing winds are from the west and northwest, which bring rainfall in the form of showers and those from the southeast, which are dry. In June, the northwest winds dominate, which have a share of 25% of the total winds; in September, the southeast winds dominate, with a share of 21.5%; and the south winds have the lowest frequency and blow especially in April and May.[2]

| Climate data for Sânnicolau Mare (2002) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

0.7 (33.3) |

5.4 (41.7) |

11 (52) |

16.3 (61.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

11.1 (52.0) |

5.2 (41.4) |

0.5 (32.9) |

10.8 (51.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 33.8 (1.33) |

28.7 (1.13) |

32.7 (1.29) |

42.5 (1.67) |

55.3 (2.18) |

79.6 (3.13) |

53.7 (2.11) |

48.2 (1.90) |

36.6 (1.44) |

29.8 (1.17) |

41 (1.6) |

45.6 (1.80) |

527.5 (20.75) |

| Source: [6] | |||||||||||||

Flora

Human activities have produced major changes in the physiognomy of the vegetation by expanding agricultural lands and reducing natural vegetation. In the Aranca Plain there are elements of flora similar to those of the entire Western Plain. In the riverside of the Aranca Canal there are agricultural lands, but also mesophile meadows: bent (Agrostis capillaris), meadow foxtail (Alopecurus pratensis), meadow-grass (Poa pratensis), meadow fescue (Festuca pratensis), red clover (Trifolium pratense), spotted medick (Medicago arabica), and among the trees: white willow (Salix alba), black poplar (Populus nigra), etc. The border of the town can be classified as a type of vegetation in the steppe, forest-steppe and oak forest. In the steppe area, the grassy layer consists of violets (Viola odorata), two-leaved squills (Scilla bifolia) and snowdrops (Galanthus nivalis). The floristic structure of the forest-steppe includes pedunculate oak (Quercus robur), downy oak (Quercus pubescens) and silver poplar (Populus alba). Within the oak forest, species of field elm (Ulmus minor) and narrow-leaved ash (Fraxinus angustifolia) appear in addition to oak.[2]

In Sânnicolau Mare, between 1970 and 1981, there were rose plantations of over 20,000 species, the town becoming symbolically the "town or roses". The most cultivated species of roses were Rosa cymosa, Rosa multiflora, Rosa × alba, Rosa × centifolia and Rosa × damascena. To these species of roses are added snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus), daisy (Bellis perennis), as well as other species that have adapted very well to the climatic conditions of the town.[6]

Fauna

The fauna is of Central European type with sub-Mediterranean elements, with penetrations and a mixture of species coming from the north, south and west of the country. The fauna of the steppe and forest-steppe is characterized by the presence of rodents such as ground squirrel, hamster, hare, and among the birds: turtle dove, nightingale, quail, grey partridge, etc. In the Aranca meadow and in the swamps around the town live numerous species of mallards, geese, herons, glossy ibises, fire-bellied toads and otters. The forest fauna is represented by roe deer, red fox, hare and squirrel, and among the birds are the same present in the steppe and forest-steppe. The fish fauna present in the Aranca Canal and in Mureș includes wels, carp, pike, Prussian carp, weatherfish and bleak.[2]

History

Antiquity

The oldest inhabitants of this land wouldbe linked to some of the first culture in Europe. Sânnicolau Mare/Cenad are some of the localities with the oldest documented history in the entire Banat. The human presence is signaled on its territory since the Neolithic, about 7,000 years ago. Archaeological cultures such as Starčevo–Criș, Vinča, Tisza and Tiszapolgár, through discoveries in several places, demonstrate the consistency of human habitation at that time.[Mesaroș, Claudiu (2013). Filosofia Sfântului Gerard de Cenad în context cultural și biografic. Szeged: JATE Press. ISBN 9789633151488.] From the Bronze Age there are archaeological discoveries of household objects and funerary urns.

The Sânnicolau Mare/Cenad then Garla Mare culture South in Mehedinti county were part of a culture that built the mightiest fortress in Europe - Cornesti Timis.

https://i1.wp.com/salvatipatrimoniultimisoarei.ro/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Foto1.png?w=850

The Bronze Age introduced solar, or Uranian, cults. Some ornaments, considered to be solar symbols, were frequently pictured on ceramic or metal parts: concentric circles, circles accompanied by rays, and the swastika. Cremation is considered to be connected to these cults.["Credinte religioase si piese de cult in epoca bronzului - Prehistoire". Prehistoire.e-monsite.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-13. Retrieved 2012-02-09.]

Just as the Cucuteni culture is considered the peak of Neolithic art, the Gârla Mare culture is considered to be the most important representation of art from the Bronze Age (1600 – 1150 BC) in Romania, standing out for the elegance of ceramic modeling and the treasure of objects of ornament, similar to the Mycenaean ones.

The Gârla Mare culture was formed in the first part of the second millennium BC. BC in the central-European area that includes the south of Slovakia and Hungary, against the background of a cultural current of inlaid ceramics, evolving along the Danube to the mouths of the Olt in the river (the area of the city of Corabia). The Transdanubian inlaid ceramics representative of the Gârla Mare culture were contributed by the Vatina culture (culture dating from the middle period of the Bronze Age, spread in the Romanian Banat and the Serbian Banat) and the elements characteristic of the areas later occupied by the tribes of this culture.

In the Romanian territory, there are three known bronze-aged sanctuaries: Sălacea, Bihor County (Ottomány culture, phase II). The only cultures of this area well represented in this regard are the Gârla Mare Zuto Brdo culture and the Bijelo Szeremle Brdo-Dalj culture (also present in Hungary and Croatia). About 340 pieces were found in the area of the two cultures, of which 244 are in the Gârla Mare area.["Credinte religioase si piese de cult in epoca bronzului - Prehistoire". Prehistoire.e-monsite.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-13. Retrieved 2012-02-09.]

https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-c5b20aab5bb73e308e15178d41072b33

Clay miniature axes (axes, hammers or double axes) belonging to this period have been found. Labrys double-axes are frequently found in the Cretan and Mycenaean worlds, where they occur most often in complex rituals and tombs (for example the Tomb of double ax of Knossos). In the Mycenaean context, the labrys has a wide range of sizes, from miniature forms to giant forms that measure 1.20 meters. However, the labrys site is frequently associated with the moon and can be a symbol of a goddess of vegetation, the forerunner of Demeter, who, on Mycenaean seals, is found under a tree. The goddess has an ax in her hand and receives as gifts poppies and fruits.

Gârla Mare as a period in history should also be linked to San Nicolau mare/Cenad, but also with Cornesti Timis (Cenad Cornesti distance is 62 km both in Timis county), the largest fortress from Europe a few times larger than Troy.

The toponym of "Iarcuri" can be associated either with the traces of border ditches or earth fortifications (wave and ditch), or with sections of old Roman roads. The term "iarc" ("border ditch") could derive either from the Turkish word ("ark", "arka") or from the Slavic word ("jarak"), the general meaning being that of "ditch", "canal", "trench".

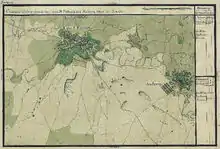

The huge size of this prehistoric fortification attracted the attention of military surveyors from the beginning of the century. XVIII. The earliest representation of the Cornești-Iarcuri fortification that we know today appears on a map drawn up in 1720 (Mappa von dem Temesvaer District). The following representations of the fortification from Cornești appear on several copies of the maps drawn up by engineer D. Haring, lieutenant C.I. Kayser and the D'Hautemont banner (the so-called "Mercy maps"), drawn up in the period 1723-1725.

The earth waves that delimit the Precincts I, II and III of the prehistoric fortification were marked by Habsburg surveyors with the toponym "Schantz Klenovaz/Schanz Kienovatz". This toponym will be preserved on different maps from the century. XVIII, among the last are the maps published in Vienna in 1765 and 1800.

Originally attributed to avar populations, the earthen mounds from Cornești are dated to the late Bronze Age (second half of the 2nd millennium BC), being built by the Cruceni-Belegiš type communities in the area.

By the same token the Sânnicolau Mare/Cenad were smaller fortresses part of the same defensive system of Cornești royal fortress, very little explored, earth waves being attributed to the Romans. Another link needing to be explored is the Vallum South of Bessarabia in Budjak region, which we find as one of the historical parts of Sânnicolau Mare. No links were tied between the two.

The fortification functioned at the end of the Bronze Age, in a world where Troy, the Mycenaean world, and the Hittite empire functioned. We are talking about a troubled time, with turmoil and many wars. Due to its very large size, the fortification raised problems for many researchers. The fortress had not only a defensive role, but also one of exhibiting the power of a community, of a warrior elite. The Roman "vallum" were not Roman.

Other inhabitants have been the Agathyrsi, named after Agathyrsus, a son of Heracles. Herodotus wrote that in 513 BC next to the Maris (Mureș) river lived the Agathyrsi who were of Thracian origin, engaging in cultivation of the land and even winemaking.[6] The Agathyrsi have over time merged with the Dacians. At that time, the hearth of the town was made up partly of swampy lands fed by the overflow of Mureș and Aranca rivers.

In 106 AD, Roman emperor Trajan conquers Dacia and transforms it into a Roman province. In the time of Trajan, the Banat of Temes was called Dacia Riparia or Ripensis, because it was surrounded by the waters of the Tisa and Mureș. He began to populate it with Roman colonies, consolidating several fortresses and earth walls. On the left bank of the Mureș, Trajan set up a Roman colony and several cohorts of Legio XIII Gemina, who built here a castrum and a town called Morisena.[7] It got its name from the Mureș and from the Dacian tribe Morasian, which had its residence here before the arrival of the Romans. Morisena would have covered the entire territory from Cenad to Sânnicolau Mare, being located between the Mureș and Aranca rivers – which at that time was navigable. Even if Morisena did not lie on the hearth of the town, there are enough scientific and military reasons to believe that in this place there was a castrum of Legio XIII Gemina erected as an outpost for the defense of Morisena.[8] Between 106 and 274 AD Morisena becomes a town under the Roman Empire. In 274 AD, emperor Aurelian withdrew his legions south of the Danube, leaving Trajan's Dacia in the hands of the Goths.

Between 380 and 396 the Huns, invading Dacia under Attila, drove the Goths south of the Danube, occupying Dacia, which they named Hunia, Morisena becoming the capital of the Hun Empire, Attila's residence. Morisena was located on a very large area, including Cenad and Sânnicolau Mare, which appear together on the map of Europe in the 5th century. The natives were spared and even respected by the Huns, living with them in harmony. Attila in his battles in the Balkan Peninsula brings Roman slaves and settles them in Dacia, strengthening the Roman element. Byzantine rhetorician Priscus, sent by emperor Theodosius II, described Attila as having royal authority, dressed simply and very religiously, and learning beautiful things from the Dacians, Hun, Latin and Roman being spoken at his court.[9] From those times are preserved the earth elevations on the border of the town called hunci, which were used as fortifications, observation points and tombs. The legends of the time say that Attila was buried on the territory of the town, in one night, in three coffins of gold, silver and iron, together with his weapons and jewelry, on the bed of the Aranca, which was then diverted.[9]

In 453, after Attila's death, the Huns were driven to the Black Sea by the Gepids, a Germanic people related to the Goths. In 566, the Gepids leave Dacia, leaving it to the Avars, a people of Tatar origin. Their khagan Bayan had his residence in Morisena, occupying this territory until 676, when Dacia was called Avaria. From the 5th century onwards, the Slavs followed in the footsteps of the Huns, and in the 7th–8th centuries they crossed the Danube during the fighting between the Byzantines and the Persians, occupied the Balkan Peninsula and formed today's Slavic peoples: Bulgarians and Serbs. Compared to the Goths, Huns, Gepids and Avars, who left without leaving too much influence, the Slavs left a strong influence in this area through Slavic toponyms and geographical names.

It is believed by some that after the Aurelian Retreat of 275 the local Daco-Roman population of the former province of Dacia began organizing itself into local administrative units yet relevant polities likely only emerged after the collapse of the Avar Khaganate around 800 AD. According to the late twelfth century Gesta Hungarorum the area of Banat was ruled by a duke called Glad at the time of the Hungarian settlement of Pannonia in 896 who ruled from Cuvin and was contemporary with dukes Gelu of Dăbâca (?) and Menumorut of Biharia.[10] Following the war between the Hungarians and Duke Glad, the latter demands peace and keeps his principality as a vassal to the Hungarian prince Árpád.

The hagiography Long Life of Saint Gerard, originally written in 1046, mentions a certain ruler called Ahtum who was governing the area of Banat at the time when King Stephen I of Hungary attacked it in 1002 from a stronghold called Urbis Morisena (literally City on the Mureș River). In the early eleventh century King Stephen I subdued lands in Transylvania, including the domain of Ahtum, who according to some estimates only held out for a few months, yet according to others as late as 1025 or even 1030, when he was defeated through the betrayal of Chanadinus, a relative of Ahtum. The fortress of Morisena was made by King Stephen I the supreme seat of the newly acquired lands, yet it was quickly rivaled by the newly established town of Cenad. Ahtum is called Ajtony in the Hungarian chronicle Gesta Hungarorum and his ethnicity is disputed (he may have been Hungarian, Kabar, Pecheneg or Romanian). Between this conquest and 1241 Morisena was under Hungarian rule. That year it was devastated by the Tatars, and after their departure, King Béla IV rebuilt the fortress on the hearth of San Nicolau. The name is said to have come from the monastery of St. Nicholas near the town, which also existed during the time of dukes Glad and Ahtum.[9] The Kemenche Monastery, located 5 km north of the town, on the left bank of the Mureș River, in the point called Seliște, also dates from this period, with the role of strengthening the Mureș line, taking on the appearance of a fortress.

Sânnicolau Mare is known for the treasure of Nagyszentmiklós, a hoard of 23 gold objects discovered here in 1799 by a Serb farmer.[11] The treasure dates from the 6th to the 10th century. No consensus has yet been reached on the origin of the treasure. The pieces of the treasure were manufactured at different times and by different masters. According to one theory, the treasure was made in the 8th century by the Avars. Another theory claimed that Bulgars made the utensil in the 9th century, and according to another study the Magyars of the Original Settlement made the treasure in the 10th century. The pieces are on display in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and the National Historical Museum in Sofia.

Middle Ages

Sânnicolau Mare first appears in written history in 1247, when it is mentioned as Zent Miklous.[12] It becomes an independent town and fortress on 17 December 1256, detaching itself from Cenad.[6] Sânnicolau Mare is mentioned in the papal tithe records of 1332 as a property of the Catholic Diocese of Cenad, named Santus Michael.[13]

Sometime between 1315 and 1331, King Charles Robert passed with his troops in the battles with Basarab I through this settlement. In 1394, Sultan Bayezid I devastated the land of Timiș, but was expelled. Some of the knightly armies of Burgundy, England and the German states passed through the town in 1396, heading for Nikopol, with peasant groups forming here in helping them in the battles against the Turks. The capital of Cenad came into the possession of the Hunyadi family on 8 August 1455, of which Sânnicolau Mare was part, and later in 1458 it came under the rule of Matthias Corvinus.

In 1481, Pál Kinizsi brought 50,000 Serbs from the Turkish-occupied territories to Banat, and some settled in the town.[7] Between 1509 and 1511, the town was hit by a plague epidemic, and in 1514 the local serf peasants took part in the revolt led by György Dózsa, which was suppressed and their leader burned on the red throne.[14] Banat with Timișoara and its localities, especially those along the Mureș, become the scene of battles between Hungarians and Turks. For the Kingdom of Hungary Banat had a defensive role, and for the Ottoman Empire it was the turning point of the system of many offensives.

The capital of Banat falls into the hands of the Turks on 30 June 1552 under Ahmed Ali Pasha, and in the same summer he conquers Sânnicolau Mare and Cenad, the first belonging to the Eyalet of Temeşvar, and the second to the Sanjak of Çanad. In 1594, some of the inhabitants, led by Vladeca Tudor and together with the army of the Ban of Karánsebes, put up resistance in the fortress of Nagybecskerek, but were defeated. In 1606, Banat passed permanently under Turkish occupation, during which time there was a Turkish barracks with a janissary school in the town aimed at defending the Mureș and Tisa rivers to the north and west.[13] Ottoman rule changed in 1701 by the Habsburg one, fifteen years earlier than Timișoara.

By the Treaty of Passarowitz (1718), concluded between the Austrians and the Ottomans, the latter demanded the demolition of the fortress of Sânnicolau Mare, after an existence of 400 years. With the Treaty of Passarowitz, the whole of Banat came under Habsburg occupation, the first governor being the cavalry general Claude Florimond de Mercy, who represented the Viennese Court.

German colonization

In 1751, following the order issued by the Imperial Court in Vienna, Count Kempe proceeded to change and transform the military government into a civilian-provincial administration. In these new circumstances, Banat will be divided into 10 districts, including Cenad with Sânnicolau Mare. The first president of the civilian-provincial administration will be Count Perlas Rialph from 1751 to 1768.

Due to the military importance of Banat as a border province and the increase in revenues obtained from this province, the Habsburg authorities are taking a series of administrative, military and cultural measures through the "Banat modernization plan". In order to implement this plan, the Imperial House of Vienna decided to colonize German population, which would contribute to a certain extent to the economic development of the province and the promotion of the Roman Catholic religion. Starting with 1752, the colonization of Swabian Germans begins, with over 145 families being brought here in three stages; they formed Sânnicolau Mare German ("German Great St. Nicholas"; German: Deutsch-Groß-Sankt-Nikolaus), with an area of 5–6 km2 and a population of over 1,500.[6] The new settlement had straight and wide streets, on either side were ditches for draining water, and the secondary streets were perpendicular to the main streets. It had a small church, a school, a parish house and a town hall built around this time.[15]

Modern history

The urban development of Sânnicolau Mare is closely linked to the Nákó family of counts. The family history of the Nákós goes back to the Middle Ages. According to the documents, the family comes from the Greek market town of Dogriani in Macedonia. The first Nákós in Banat were brothers Christoph and Cyril Nákó. They bought most of the Sânnicolau Mare estate at an auction of animals and goods in 1781.[16]

On 11 June 1787, Sânnicolau Mare received approval for the organization of an annual fair and, starting with 6 July 1837, for the organization of a weekly fair. Its value as a locality also materialized through the postal road that connected the diligences and stagecoaches between Timișoara–Budapest–Vienna (Sânnicolau Mare being a station for changing horses). In fact, in German documents from 1837, the name oppidum also appears,[17] which means that the locality itself was the basis of a town. Due to a great fire in Nagybecskerek, the county seat, the headquarters of the prefecture of Torontál County was moved to Sânnicolau Mare between 1807 and 1820.

The revolutionary year 1848 was also felt in Sânnicolau Mare, many locals participating in the revolutionary battles, even constituting an area called Sânnicolau Mare Sârbesc ("Serbian Great St. Nicholas"; Serbian: Српски Велики Семиклуш, romanized: Srpski Veliki Semikluš) being included in the province of Serbian Voivodeship.

During 1850–1853, judicial activities began, the Nákó Castle was built in neoclassical style, as well as the Vălcani–Periam railway. Twenty years later, after the Mureș flood, the Aranca Canal is cleared and arranged. In 1883 the first hospital was established by a philanthropic gesture of Count Nákó.

Starting with the years 1867 of the Austro-Hungarian dualism, with all the difficulties encountered, the locality continued its economic, social and cultural development. Thus, between 1867 and 1918, there were dozens of workshops, manufactories, banks, bakeries, slaughterhouses, doctor's offices and veterinary clinics, tanneries, cartwright's workshops, woodworks, cattle shopkeepers, brickworks, vine growers, farms, as well as a brewery, a brick factory and a tile factory. There were also bookstores, weaving mills, pharmacies and a number of craftsmen such as mechanics, tailors, chimney sweepers, rope makers, watchmakers and locksmiths.[15] The construction of Periam–Vălcani (1870), Sânnicolau Mare–Timișoara (1895), Sânnicolau Mare–Cenad–Makó (1905) and Sânnicolau Mare–Arad (1905) railways led to the emergence of other economic sectors, which gave the locality the status of a town and a zonal center. It had an area of 17,690 jugers (3,100 ha), one juger representing 0.57 ha, and the Zăbrani forest had an area of 550 jugers and stretched from Izlaz to Cenad, and the number of inhabitants was 11,358, with Romanians and Germans predominating, followed by Hungarians and Serbs.[6]

Between 1910 and 1941, Sânnicolau Mare was a commune belonging to Torontál County, as well as a plasă seat. It became a town on 26 June 1942 through Law no. 495 issued by Ion Antonescu which provided for the merger of Sânnicolau Mare and Sânnicolau German into one.[18] Between 1951 and 1968, it was a raion seat, and since 1968 it has been a town of Timiș County, and in this period the town expanded territorially through the development of industrial areas in the north and south.

Demographics

With 12,312 inhabitants at the 2011 census, Sânnicolau Mare is the third largest town in Timiș County.

Ethnic composition

According to the 2011 census, most inhabitants are Romanians (73.7%), larger minorities being represented by Hungarians (7.23%), Roma (3.14%), Bulgarians (2.98%), Serbs (2.98%) and Germans (2.1%). For 7.46% of the population, ethnicity is unknown.[19]

In Sânnicolau Mare the population is and has always been heterogeneous. 17 nationalities and probably others not included in the statistics have lived in the town over time. The record was set in 1977, when 15 nationalities were counted, even though three of them had only one representative.[6] By 1750 there were already several families of Serbs and Germans here. The first accurate data come from 1880. In that year Germans had the largest share of the population (41.17%), with 1,782 Germans in Sânnicolau German compared to 2,805 Germans in Sânnicolau Mare. So a total of 4,462 Germans, followed by Romanians (31.28%), Serbs (11.39%), Hungarians (10.81%) and 3.35% other nationalities. Germans settled in Sânnicolau Mare in three waves: 1752, 1763–1765 and 1766–1773. Several Aromanian and Greek families also arrived from Macedonia, with 427 Greeks living here by the end of the 18th century.[14]

| Census[21] | Ethnic composition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | Romanians | Hungarians | Germans | Jews | Roma | Serbs | Bulgarians |

| 1880 | 10,836 | 3,528 | 1,219 | 4,678 | – | – | 1,285 | – |

| 1890 | 12,311 | 4,099 | 1,496 | 5,355 | – | – | 1,264 | – |

| 1900 | 12,639 | 4,179 | 1,928 | 5,197 | – | – | 1,238 | – |

| 1910 | 12,357 | 4,025 | 2,163 | 4,823 | – | – | 1,136 | – |

| 1920 | 10,900 | 3,937 | 1,160 | 4,366 | 400 | – | – | – |

| 1930 | 10,676 | 4,266 | 1,236 | 3,759 | 362 | 191 | 800 | 32 |

| 1941 | 10,640 | 4,481 | 1,078 | 3,720 | – | – | – | – |

| 1948 | 9,789 | 5,225 | 1,208 | 2,518 | 15 | – | – | – |

| 1956 | 9,956 | 5,433 | 1,236 | 2,430 | 25 | 77 | 644 | 79 |

| 1966 | 11,428 | 6,790 | 1,243 | 2,454 | 15 | 37 | 736 | 119 |

| 1977 | 12,811 | 7,970 | 1,395 | 2,434 | 13 | 132 | 607 | 204 |

| 1992 | 13,083 | 9,609 | 1,389 | 770 | – | 256 | 599 | 407 |

| 2002 | 12,914 | 9,917 | 1,209 | 411 | – | 364 | 463 | 468 |

| 2011 | 12,312 | 9,074 | 890 | 259 | – | 386 | 367 | 367 |

Religious composition

According to the 2011 census, most inhabitants are Orthodox (63.13%), but there are also minorities of Roman Catholics (17.49%), Pentecostals (4.41%), Serbian Orthodox (2.53%) and Greek Catholics (2.01%). For 7.55% of the population, religious affiliation is unknown.[20]

The religious composition is closely linked to the ethnic composition. Thus, in Sânnicolau Mare, almost all Romanians and Serbs have been Orthodox, almost all Germans, Hungarians and Bulgarians have been Catholic.[6] The first data on the religious composition of the population come from 1839. Then the Orthodox had the largest share with 57.97% (5,748 people), followed by Roman Catholics with 35.69% (3,569 people) and 6.34% of other religions: 308 Mosaics (Jews), 172 Reformed, 148 Evangelics (Lutherans).

Culture

Music

Sânnicolau Mare is the birthplace of two famed musicians: composer Béla Bartók and violinist Károly Szénassy. The town is also noted for Doina choir, with a vast cultural activity in the area since the 19th century. Originally made up of 18 young serfs, the choir was founded in 1838 at the initiative of teacher Simion Andron. This choir began singing in two voices, in Church Slavonic and Greek, on Easter Day 1839 for the first time in the town. On its centenary, the Doina choir was decorated by Law no. 472/1958 with the Second-class Work Order. Choir activity ceased in 2003.[22]

Press, media and literature

Sânnicolau Mare is the birthplace of Emilia Lungu-Puhallo, the first woman journalist in Banat and Transylvania.

Between 1873 and 1890, under the editorship of Damian Petrovici, the specialized magazine Apicultorul appears, being the first of its kind in the country. The first local newspaper, Nagyszentmiklósi közlöny, issued in the Hungarian language by Viktor Schreyer, appears in 1879. The newspaper resists until 1914, when it changes its title into Felső-Torontál/Torontalul de Sus and appears also in the Romanian language.[23] The first German newspaper, Südungarische Volksblatt, appears in 1882 and is published by the first printing house in the town, belonging to Natahail Wienwier. Through professor Teodor Bucurescu, the weekly newspaper Primăvara appears in 1921, with 2,000 copies per week, through which it exposes the realities of the town and the aspirations of the locals, and from 1923 the Primăvara calendar is published. After 1990, an attempt was made to republish the newspaper Primăvara by the Town Hall, but, due to lack of funds, it was not published. Since 2000, only the Town Hall newsletter has been published in the town; magazines for internal use are also published at the Ioan Jebelean Theoretical High School (Necuvântul) and at the General School no. 1 (Lumea Noastră).[6]

Economy

The town's economy has seen a trend reversal in recent years, due to its strategic position on the western border of the country, which has attracted a number of important investors. The largest companies are the American company Delphi Packard (electrical wiring for car components manufactured by international groups), with over 4,300 employees, and the Italian company Zoppas Industries (electrical resistors), with over 2,500 employees. Due to the high demand for labor, the industrial pole thus created provides jobs to the surrounding localities.

Sânnicolau Mare was declared in 2020 a tourist resort of local interest.[24] Tourist attractions include the 19th-century Nákó Castle (housing the Cultural House and the Town Museum), the Serbian Orthodox church (1787), the Roman Catholic church (1824) with a crypt of the Nákó family, the Romanian Orthodox church (1903) and the Reformed church (1913).

Transport

Road transport

Sânnicolau Mare is connected to the Romanian national road network by national road 6 and national road 59C, being also crossed by county road 59F, which provides a direct road connection with the Beba Veche border crossing point at Triplex Confinium.

Rail transport

Sânnicolau Mare is connected to the railway network of Căile Ferate Române by CFR 218 (Timișoara–Cenad) railway, which connects Timișoara with the west of Timiș County, at the border point with Hungary.

The town has two stations:

- the Main Station (Romanian: Gara Mare), to the south, with loading and unloading ramps, being also a four-way railway junction;

- the Small Station (Romanian: Gara Mică), to the north, a railway stop.

Public transport

The town does not have an organized urban transport, due to its concentric configuration, the public service providing only two buses for transporting people to the Main Station, upon arrival of passenger trains from Timișoara and Arad. Private operators provide passenger transport between Sânnicolau Mare and neighboring localities or other counties.

Sports

Over time, the sports movement has had a tradition inclined to the existing branches of sports in each historical stage, depending on economic development and social conditions. With the colonization of Swabian Germans, sports activities diversified, taking place both locally and in the surrounding localities, in various sports existing at that time.

The emergence in 1860 of the Sokol movement in Czech lands has also an impact on the sports in Sânnicolau Mare, which materializes in 1924, when the Physical Education Society "Falcons of Romania" is created.[25] The Falcons participated in the 9th All Sokol Rally in Prague in 1932, where they won a gold medal. The Falcons of Romania played a very important role in the physical education movement in the schools of Timiș-Torontal and Arad counties, and in Sânnicolau Mare the first sports hall was built in the yard of the Prince Carol Gymnasium (present-day Agricultural School Group).

In 1902, the first football team was created, called the Sânmiclăușana Sports Association, which carried out its activity on the field near the Small Station, and later on the field on Timișoara Street, where football matches were played with teams from the surrounding localities. The football activity resumed in 1953, when the town stadium was built with a capacity of 5,000 seats and a main grandstand, where the Unirea football team will evolve.[6]

The town's women's volleyball team won the republican championship three years in a row between 1958 and 1960.

In order to carry out winter activities and indoor sports, the Sports Hall was built, which is intended for women's and men's handball matches, sports activities for students in general and high schools, gymnastics and football matches. The Sport Hotel and a sports hostel were built for the accommodation of the athletes. The Olympic-size pool of the public pool is used only for leisure activities and not for sports activities. In 2002, a kart circuit was built in the southwestern part of the town, where national and international competitions are held. The hippodrome was built in 1985 in the northeastern part of the town, on Țichindeal Street, with an obstacle course circuit, an arbitration grandstand, a grandstand with a capacity of 400 seats, stables, an administrative building and a park at the entrance.[6]

Twin towns – sister cities

Sânnicolau Mare is twinned with:[26]

Burgkirchen an der Alz, Germany

Burgkirchen an der Alz, Germany Kazincbarcika, Hungary

Kazincbarcika, Hungary Potenza Picena, Italy

Potenza Picena, Italy

Notable people

- Adolph Huebsch (1830–1884), scholar and rabbi

- Emilia Lungu-Puhallo (1853–1932), journalist and teacher

- Atanasie Lipovan (1874–1947), composer, singer and conductor

- Béla Bartók (1881–1945), composer, pianist and ethnomusicologist

- Lipót Herman (1887–1972), painter

- Hans Röhrich (1899–1988), surgeon and university lecturer

- Wilhelm Totok (1921–2017), author, editor and librarian

- Ion Hobana (1931–2011), writer, literary critic and ufologist

- Francisc Bárányi (1936–2016), doctor and politician

- Hans Dama (b. 1944), writer and scientist

- Gheorghe Funar (b. 1949), politician

- Werner Kremm (b. 1951), publicist, translator and editor

- Anton Sterbling (b. 1953

- Dușan Baiski (b. 1955), writer and publicist

- Hartmut Mayerhoffer (b. 1969), handball player

- Cristian Bălgrădean (b. 1988), footballer

- Sabrin Sburlea (b. 1989), footballer

- Mihai Eftimie Bogdan (1891-1972), evangelist

References

- "Results of the 2020 local elections". Central Electoral Bureau. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- "Strategia de dezvoltare a orașului Sânnicolau Mare 2017-2020" (PDF). Primăria orașului Sânnicolau Mare.

- "Populaţia rezidentă după grupa de vârstă, pe județe și municipii, orașe, comune, la 1 decembrie 2021" (XLS). National Institute of Statistics.

- "Ortschaften mit ehem. deutscher Bevölkerung im Banat". Jetscha.de.

- "Harta digitală a orașului Sânnicolau Mare". Primăria orașului Sânnicolau Mare.

- Romoșan, Ioan (2000). Monografia orașului Sânnicolau Mare. Timișoara: Solness.

- Muntean, Vasile V. (1990). Contribuții la istoria Banatului. Timișoara: Editura Mitropoliei Banatului.

- Olteanu, Constantin (1984). Istoria militară a poporului român. Bucharest: Editura Militară.

- Cotoșman, Gheorghe (1934). Din trecutul Banatului. Vol. II. Timișoara: Sonntogsblatt.

- Iorga, Nicolae (1989). Istoria românilor din Ardeal și Ungaria. Bucharest: Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică. ISBN 973-29-0064-4.

- László, Gyula; Rácz, István (1984). The Treasure of Nagyszentmiklós. Corvina Kiadó. p. 19. ISBN 9631318117.

- Györffy, György (1963). Az Árpád-kori Magyarország történeti földrajza. Vol. I. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Barbu, Dinu (2013). Mic atlas al județului Timiș (caleidoscop) (PDF) (5th ed.). Timișoara: Artpress. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-973-108-553-1.

- Barna, Bodó (2009). "Sânnicolau Mare". Ghid cronologic al orașelor (PDF). Timișoara: Marineasa. pp. 95–100. ISBN 978-973-631-570-1.

- Haas, Hans (2016). Contribuții la istoria localității urbane Sânnicolau Mare și a împrejurimilor nemijlocite (PDF).

- Haas, Hans (2017). Neamul nobiliar Nákó de Nagyszentmiklós. Ascensiunea și declinul unei dinastii de conți (PDF). Timișoara: Diacritic. ISBN 978-606-8857-05-3.

- Szőcs, I. (1972). Colonizarea germanilor șvabi din Sânnicolau Mare.

- "Legea Nr. 495 pentru contopirea comunelor rurale Sânnicolaul Mare și Sânnicolaul German din județul Timiș-Torontal într-o singură comună, denumită "Sânnicolaul Mare" și declararea acesteia de comună urbană" (PDF). Monitorul Oficial. 110 (148): 5299–5300. 29 June 1942.

- "Tab8. Populația stabilă după etnie – județe, municipii, orașe, comune". Institutul Național de Statistică.

- "Tab13. Populația stabilă după religie – județe, municipii, orașe, comune". Institutul Național de Statistică.

- Varga, E. Árpád. "Temes megye településeinek etnikai (anyanyelvi/nemzetiségi) adatai 1880-2002" (PDF).

- Căliman, Ion (2018). Corul "Doina" și dirijorul Radu Gheorghe. Timișoara: Mirton. ISBN 9789735217952.

- "Publicațiile Periodice Românești - PPR Tom. IV. (1925-1930)". Biblioteca Academiei Române.

- Szendrei, Ildiko (23 October 2020). "Orașele Anina și Sânnicolau Mare au devenit stațiuni turistice de interes local". Express de Banat.

- Farca, I.V. (1932). Șoimii României la Praga.

- "Localități înfrățite" (in Romanian). Sânnicolau Mare. Retrieved 10 May 2022.