Elvish languages of Middle-earth

The Elvish languages of Middle-earth, constructed by J. R. R. Tolkien, include Quenya and Sindarin. These were the various languages spoken by the Elves of Middle-earth as they developed as a society throughout the Ages. In his pursuit for realism and in his love of language, Tolkien was especially fascinated with the development and evolution of language through time. Tolkien created two almost fully developed languages and a dozen more in various beginning stages as he studied and reproduced the way that language adapts and morphs. A philologist by profession, he spent much time on his constructed languages. In the collection of letters he had written, posthumously published by his son, Christopher Tolkien, he stated that he began stories set within this secondary world, the realm of Middle-earth, not with the characters or narrative as one would assume, but with a created set of languages. The stories and characters serve as conduits to make those languages come to life. Inventing language was always a crucial piece to Tolkien's mythology and world building. As Tolkien stated:

The invention of languages is the foundation. The 'stories' were made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse. To me a name comes first and the story follows.[T 1]

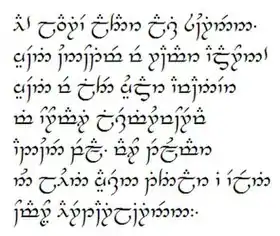

Tolkien created scripts for his Elvish languages, of which the best known are Sarati, Tengwar, and Cirth.[1]

External history

Language construction

J. R. R. Tolkien began to construct his first Elvin tongue c. 1910–1911 while he was at the King Edward's School, Birmingham and which he later named Quenya (c. 1915). At that time, Tolkien was already familiar with Latin, Greek, Italian, Spanish, and several ancient Germanic languages, Gothic, Old Norse and Old English. He had invented several cryptographic codes such as Animalic, and two or three constructed languages including Naffarin. He then discovered Finnish, which he described many years later as "like discovering a complete wine-cellar filled with bottles of an amazing wine of a kind and flavour never tasted before. It quite intoxicated me."[T 2] He had started his study of the Finnish language to be able to read the Kalevala epic.

The ingredients in Quenya are various, but worked out into a self-consistent character not precisely like any language that I know. Finnish, which I came across when I first begun to construct a 'mythology' was a dominant influence, but that has been much reduced [now in late Quenya]. It survives in some features: such as the absence of any consonant combinations initially, the absence of the voiced stops b, d, g (except in mb, nd, ng, ld, rd, which are favoured) and the fondness for the ending -inen, -ainen, -oinen, also in some points of grammar, such as the inflexional endings -sse (rest at or in), -nna (movement to, towards), and -llo (movement from); the personal possessives are also expressed by suffixes; there is no gender.[T 3]

Tolkien with his Quenya pursued a double aesthetic goal: "classical and inflected".[T 4] This urge, in fact, was the motivation for his creation of a 'mythology'. While the language developed, he needed speakers, history for the speakers and all real dynamics, like war and migration: "It was primarily linguistic in inspiration and was begun in order to provide the necessary background of 'history' for Elvish tongues".[T 5][2]

The Elvish languages underwent countless revisions in grammar, mostly in conjugation and the pronominal system. The Elven vocabulary was not subject to sudden or extreme change; except during the first conceptual stage c. 1910–c. 1920. Tolkien sometimes changed the "meaning" of an Elvish word, but he almost never disregarded it once invented, and he kept on refining its meaning, and countlessly forged new synonyms. Moreover, Elven etymology was in a constant flux. Tolkien delighted in inventing new etymons for his Elvish vocabulary.

From the outset, Tolkien used comparative philology and the tree model as his major tools in his constructed languages. He usually started with the phonological system of the proto-language and then proceeded in inventing for each daughter language the many mechanisms of sound change needed.

I find the construction and the interrelation of the languages an aesthetic pleasure in itself, quite apart from The Lord of the Rings, of which it was/is in fact independent.[T 6]

In the early 30s Tolkien decided that the proto-language of the Elves was Valarin, the tongue of the gods or Valar: "The language of the Elves derived in the beginning from the Valar, but they change it even in the learning, and moreover modified and enriched it constantly at all times by their own invention."[T 7] In his Comparative Tables, Tolkien describes the mechanisms of sound change in the following daughter languages: Qenya, Lindarin (a dialect of Qenya), Telerin, Old Noldorin (or Fëanorian), Noldorin (or Gondolinian), Ilkorin (esp. of Doriath), Danian of Ossiriand, East Danian, Taliska, West Lemberin, North Lemberin, and East Lemberin.[T 8]

In his lifetime J.R.R. Tolkien never ceased to experiment on his constructed languages, and they were subjected to many revisions. They had many grammars with substantial differences between different stages of development. After the publication of The Lord of the Rings (1954–1955), the grammar rules of his major Elvish languages Quenya, Telerin and Sindarin went through very few changes (this is late Elvish 1954–1973).

Publication of Tolkien's linguistic papers

Two magazines (Vinyar Tengwar, from its issue 39 in July 1998, and Parma Eldalamberon, from its issue 11 in 1995) are exclusively devoted to the editing and publishing of J.R.R. Tolkien's gigantic mass of previously unpublished linguistic papers (including those omitted by Christopher Tolkien from "The History of Middle-earth"). However, no new publications have appeared since 2015. Access to the unpublished documents is severely limited, and the editors have yet not published a comprehensive catalogue of the documents they are working on.

Internal history

| Internal history of Tolkien's Elvish languages | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primitive Quendian the tongue of all Elves at Cuiviénen | ||||||

| Common Eldarin the tongue of the Elves during the March |

Avarin combined languages of the Avari (at least six), some later merged with Nandorin | |||||

| Quenya the language of the Ñoldor and the Vanyar |

Common Telerin the early language of all the Lindar | |||||

| Quendya also Vanyarin Quenya, daily tongue of the Vanyar |

Exilic Quenya also Ñoldorin Quenya, colloquial speech of the Noldor |

Telerin the language of the Teleri who reached the Undying Lands; a dialect of Quenya |

Sindarin language of the Sindar |

Nandorin languages of the Nandor, some were influenced by Avarin | ||

The Elvish languages are a family of several related languages and dialects. Here is set briefly the story of the Elvish languages as conceived by Tolkien around 1965. They all originated from:

- Primitive Quendian or Quenderin, the proto-language of all the Elves who awoke together in the far east of Middle-earth, Cuiviénen, and began "naturally" to make a language. All the Elvish languages are presumed to be descendants of this common ancestor.

Tolkien invented two subfamilies (subgroups) of the Elvish languages. "The language of the Quendelie (Elves) was thus very early sundered into the branches Eldarin and Avarin".[T 9]

- Avarin is the language of various Elves of the Second and Third Clans, who refused to come to Valinor. It developed into at least six Avarin languages.

- Common Eldarin is the language of the three clans of the Eldar during the Great March to Valinor. It developed into:

- Quenya, the language of the Elves in Eldamar beyond the Sea; it divided into:

- Common Telerin, the early language of all the Teleri

- Telerin, the language of the Teleri, Elves of the Third Clan, living in Tol Eressëa and Alqualondë.

- Nandorin, the language of the Nandor, a branch of the Third Clan. It developed into various Nandorin and Silvan languages.

- Sindarin is the language of the Sindar, a branch of the Third Clan, who dwelt in Beleriand. Its dialects include Doriathrin, in Doriath; Falathrin, in the Falas of Beleriand; North Sindarin, in Dorthonion and Hithlum; Noldorin Sindarin, spoken by the Exiled Noldor.

The acute accent (á, é, í, ó, ú) or circumflex accent (â, ê, î, ô, û, ŷ) marks long vowels in the Elvish languages. When writing Common Eldarin forms, Tolkien often used the macron to indicate long vowels. The diaeresis (ä, ë, ö) is normally used to show that a short vowel is to be separately pronounced, that it is not silent or part of a diphthong. For example, the last four letters of Ainulindalë represent two syllables, and the first three letters of Eärendil represent two syllables.

Internal development of the Elvish word for "Elves"

Below is a family tree of the Elvish languages, showing how the Primitive Quendian word kwendī "people" (later meaning "Elves") was altered in the descendant languages.[T 10]

| Time Period | Languages | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Awakening | Primitive Quendian The tongue of all Elves at Cuiviénen kwendī | |||||

| The Westward March | Quenya Vanyar and Noldor Quendi |

Common Eldarin The tongue of the Elves during the March Kwendī |

Avarin Avari, those Elves who stayed at Cuiviénen and from there spread across Middle-earth (many languages) Kindi, Cuind, Hwenti, Windan, Kinn-lai | |||

| The First Age of the Sun | Telerin Teleri in Aman Pendi |

Sindarin Elves of the Third Clan in Beleriand did not use it: "P.Q. *kwende, *kwendī disappeared altogether."[T 10] The exiled Noldor used in their Sindarin: Penedh, pl. Penidh[T 11] |

Nandorin Elves of Ossiriand sg. Cwenda[T 11] |

|||

| Silvan[lower-alpha 1] The Wood-elves of the Vale of Anduin Penni |

||||||

The languages can thus be mapped to the migrations of the sundered elves.[T 10]

Fictional philology

A tradition of philological study of Elvish languages exists within the fiction of Tolkien's frame stories. Elven philologists are referred to by the Quenya term Lambengolmor. In Quenya, lambe means "spoken language" or "verbal communication."

The older stages of Quenya were, and doubtless still are, known to the loremasters of the Eldar. It appears from these notices that besides certain ancient songs and compilations of lore that were orally preserved, there existed also some books and many ancient inscriptions.[T 12]

Known members of the Lambengolmor were Rúmil, who invented the first Elvish script (the Sarati), Fëanor who later enhanced and further developed this script into his Tengwar, which later was spread to Middle-earth by the Exiled Noldor and remained in use ever after, and Pengolodh, who is credited with many works, including the Osanwe-kenta and the Lhammas or "The 'Account of Tongues' which Pengolodh of Gondolin wrote in later days in Tol-eressëa".[T 13]

Independently of the Lambengolmor, Daeron of Doriath invented the Cirth or Elvish-runes. These were mostly used for inscriptions, and later were replaced by the Tengwar, except among the Dwarves.

Pronunciation of Quenya and Sindarin

Sindarin and Quenya have similar pronunciations. The following table gives pronunciation for each letter or cluster in international phonetic script and examples:

Vowels

| Letter / Digraph | Pronunciation | IPA | Further comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | as in father, but shorter. | [ɑ] | never as in cat [*æ] |

| á | as in father | [ɑˑ] | . |

| â | (in Sindarin) as in father, but even longer | [ɑː] | . |

| ae | (in Sindarin) the vowels described for a and e in one syllable. | [ɑɛ̯] | Similar to ai |

| ai | a diphthong, similar to that in eye, but with short vowels | [ɑɪ̯] | never as in rain [*eɪ] |

| au | a and u run together in one syllable. Similar to the sound in house | [ɑʊ̯] | never as in sauce [*ɔ] |

| aw | (in Sindarin) a common way to write au at the end of the word | [ɑʊ̯] | . |

| e | as in pet | [ɛ] | . |

| é | the same vowel lengthened (and in Quenya more closed; as in German) | S: [ɛˑ], Q: [eˑ] | Rural Hobbit pronunciation allows the sound as in English rain |

| ê | (in Sindarin) the vowel of pet especially lengthened | [ɛː] | Rural Hobbit pronunciation allows the sound as in English rain |

| ei | as in eight | [ɛɪ̯] | never as in either (in neither pronunciation) [*i] [*aɪ] |

| eu | (in Quenya) e and u run together in one syllable | [ɛʊ̯] | never as in English or German [*ju] [*ɔʏ] |

| i | as in machine, but short | [i] | not opened as in fit [*ɪ] |

| í | as in machine | [iˑ] | . |

| î | (in Sindarin) as in machine, but especially lengthened | [iː] | . |

| iu | (in Quenya) i and u run together in one syllable | [iʊ̯] | later by men often as in English you [ju] |

| o | open as in sauce, but short | [ɔ] | . |

| ó | the same vowel lengthened (and in Quenya more closed; as in German) | S: [ɔˑ], Q: [oˑ] | Rural Hobbit pronunciation allows the sound of "long" English cold [oː] |

| ô | (in Sindarin) the same vowel especially lengthened | [ɔː] | Rural Hobbit pronunciation allows the sound of "long" English cold [oː] |

| oi | (in Quenya) as in English coin | [ɔɪ̯] | . |

| oe | (in Sindarin) the vowels described for o and e in one syllable. | [ɔɛ̯] | Similar to oi. Cf. œ! |

| œ | (in early Sindarin) as in German Götter | [œ] | in published writing, has been incorrectly spelt oe (two letters), as in Nírnaeth Arnoediad. Later became e. |

| u | as in cool, but shorter | [u] | not opened as in book [*ʊ] |

| ú | as in cool | [uˑ] | . |

| û | (in Sindarin) the same vowel as above, but especially lengthened | [uː] | . |

| y | (in Sindarin) as in French lune or German süß, but short | [y] | not found in English; like the vowel sound in "lure", but with pursed lips. |

| ý | (in Sindarin) as in French lune or German süß | [yˑ] | . |

| ŷ | (in Sindarin) as in French lune or German süß, but even longer | [yː] |

Consonants (differing from English)

- The letter c always denotes [k], even before i and e; for instance, Celeborn is pronounced Keleborn, and Cirth is pronounced Kirth; thus, it never denotes the soft c [*s] in cent.

- The letter g always denotes the hard [ɡ], as in give, rather than the soft form [*d͡ʒ], as in gem.

- The letter r denotes an alveolar trill [r], similar to Spanish rr.

- The digraph dh, as in Caradhras, denotes [ð] as in English this.

- The digraph ch, as in Orch, denotes [χ] as in Welsh bach, and never like the ch [*t͡ʃ] in English chair.

- The digraph lh denotes [ɬ] as in Welsh ll.

Elvish scripts

Tolkien wrote out most samples of Elvish languages with the Latin alphabet, but within the fiction he imagined many writing systems for his Elves. The best-known are the "Tengwar of Fëanor", but the first system he created, c. 1919, is the "Tengwar of Rúmil", also called the sarati. In chronological order, Tolkien's scripts are:[3]

- Tengwar of Rúmil or Sarati

- Gondolinic runes (Runes used in the city of Gondolin)

- Valmaric script

- Andyoqenya

- Qenyatic

- Tengwar of Fëanor

- The Cirth of Daeron

Prior to their exile, the Elves of the Second Clan (the Noldor) used first the Sarati of Rúmil to record their tongue, Quenya. In Middle-earth, Sindarin was first recorded using the "Elvish runes" or Cirth, named later certar in Quenya. A runic inscription in Quenya was engraved on Aragorn's sword, Andúril. The sword's inscriptions were not shown in the movie trilogy, nor in the book.

The Etymologies

The Etymologies is Tolkien's etymological dictionary of the Elvish languages, written during the 1930s. It was edited by Christopher Tolkien and published as the third part of The Lost Road and Other Writings, the fifth volume of the History of Middle-earth. Christopher Tolkien described it as "a remarkable document." It is a list of roots of the Proto-Elvish language, from which J. R. R. Tolkien built his many Elvish languages, especially Quenya, Noldorin and Ilkorin. The Etymologies do not form a unified whole, but incorporate layer upon layer of changes. It was not meant to be published. In his introduction to The Etymologies, Christopher Tolkien wrote that his father was "more interested in the processes of change than he was in displaying the structure and use of the languages at any given time."[T 14]

The Etymologies has the form of a scholarly work listing the "bases" or "roots" of the protolanguage of the Elves: Common Eldarin and Primitive Quendian. Under each base, the next level of words (marked by an asterisk) are "conjectural", that is, not recorded by Elves or Men (it is not stated who wrote The Etymologies inside Middle-earth) but presumed to have existed in the proto-Elvish language. After these, actual words which did exist in the Elvish languages are presented. Words from the following Elvish languages are presented: Danian, Doriathrin (a dialect of Ilkorin), Eldarin (the proto-language of the Eldar), (Exilic) Noldorin, Ilkorin, Lindarin (a dialect of Quenya), Old Noldorin, Primitive Quendian (the oldest proto-language), Qenya, Telerin.

The following examples from The Etymologies illustrate how Tolkien worked with the "bases":

- BAD- *bad- judge. Cf. MBAD-. Not in Q [Qenya]. N [Noldorin] bauð (bād-) judgement; badhor, baðron judge.

- TIR- watch, guard. Q tirin I watch, pa.t. [past tense] tirne; N tiri or tirio, pa.t. tiriant. Q tirion watch-tower, tower. N tirith watch, guard; cf. Minnas-tirith. PQ [Primitive Quendian] *khalatirnō 'fish-watcher', N heledirn = kingfisher; Dalath Dirnen 'Guarded Plain'; Palantir 'Far-seer'.

This organization reflects what Tolkien did in his career as a philologist. With English words, he worked backwards from existing words to trace their origins. With Elvish he worked both backward and forward. The etymological development was always in flux but the lexicon of the Elvish tongues remained rather stable. An Elvish word (Noldorin or Quenya) once invented would not change or be deleted but its etymology could be changed many times.

Tolkien was much interested in words. Thus The Etymologies are preoccupied with them, and only a few Elvish phrases are presented. The Etymologies discuss mainly the Quenya, Old Noldorin, and Noldorin languages. The text gives many insights into Elvish personal and place names which otherwise would remain opaque.

Christopher Tolkien stated that his father "wrote a good deal on the theory of sundokarme or 'base structure' ... but like everything else it was frequently elaborated and altered".[T 14] In 2003 and 2004, Vinyar Tengwar issues 45 and 46 provided addenda and corrigenda to the original published text.

Notes

References

Primary

- Carpenter 1981 #165 to Houghton Mifflin, June 1955

- Carpenter 1981 #214 to A. C. Nunn, late 1958

- From a letter to W. R. Matthews, dated 13–15 June 1964, published in Parma Eldalamberon 17, p. 135.

- Parma Eldalamberon 17, p. 135

- Tolkien, J. R. R. The Lord of the Rings, "Foreword to the Second Edition".

- Letter from Tolkien to a reader, published in Parma Eldalamberon 17, p. 61

- J.R.R. Tolkien, "Lambion Ontale: Descent of Tongues", "Tengwesta Qenderinwa" 1, Parma Eldalamberon 18, p. 23.

- Parma Eldalamberon, 19, pp. 18–28

- J.R.R. Tolkien, "Tengwesta Qenderinwa", Parma Eldalamberon 18, p. 72

- Tolkien 1994, "Quendi and Eldar"

- Tolkien 1987, "The Etymologies"

- J.R.R. Tolkien, "Outline of Phonology", Parma Eldalamberon 19, p. 68.

- Tolkien 1987, "The Lhammas"

- Tolkien 1987, pp. 378–379

Secondary

- Hostetter, Carl F. (2013) [2007]. "Languages Invented by Tolkien". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 332–343. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Hostetter, Carl F., "Elvish as She Is Spoke". Republished with permission from The Lord of the Rings 1954–2004: Scholarship in Honor of Richard E. Blackwelder Archived 2006-12-09 at the Wayback Machine (Marquette, 2006), ed. Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull.

- Smith, Arden R. "Writing Systems". The Tolkien Estate. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

Sources

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-31555-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1994). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The War of the Jewels. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-71041-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1987). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Lost Road and Other Writings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-45519-7.

Bibliography

This section lists the many sources by Tolkien documenting Elvish texts.

Books

A small fraction of Tolkien's accounts of Elvish languages was published in his novels and scholarly works during his lifetime.

- The Hobbit (1937) and The Adventures of Tom Bombadil (1962) contain a few elvish names (Elrond, Glamdring, Orcrist), but no texts or sentences.

- 1954–1955 The Lord of the Rings.

- 1968 The Road Goes Ever On.

- 1981 the "Oath of Cirion" in Unfinished Tales.

- 1983 "A Secret Vice" in The Monsters and the Critics, with Oilima Markirya, Nieninqe, and Earendel.

- 1985 "Fíriel's Song", in The Lost Road and Other Writings, p. 72.

- 1985 "Alboin Errol's Fragments", in The Lost Road and Other Writings, p. 47.

Posthumous articles

Many of Tolkien's writings on his invented languages have been annotated and published by Carl F. Hostetter in the journals Vinyar Tengwar and Parma Eldalamberon, as follows:

- 1989 "The Plotz Quenya Declensions", first published in part in the fanzine Beyond Bree, and later in full in "Vinyar Tengwar 6, p. 14.

- 1991 "Koivieneni Sentence" in Vinyar Tengwar 14, pp. 5–20.

- 1992 "New Tengwar Inscription" in Vinyar Tengwar 21, p. 6.

- 1992 "Liège Tengwar Inscription" in Vinyar Tengwar 23, p. 16.

- 1993 "Two Trees Sentence" in Vinyar Tengwar 27, pp. 7–42.

- 1993 "Koivieneni Manuscript" in Vinyar Tengwar 27, pp. 7–42.

- 1993 "The Bodleian Declensions", in Vinyar Tengwar 28, pp. 9–34.

- 1994 "The Entu Declension" in Vinyar Tengwar 36, pp. 8–29.

- 1995 "Gnomish Lexicon", Parma Eldalamberon 11.

- 1995 "Rúmilian Document" in Vinyar Tengwar 37, pp. 15–23.

- 1998 "Qenya Lexicon" Parma Eldalamberon 12.

- 1998 "Osanwe-kenta, Enquiry into the communication of thought", Vinyar Tengwar 39

- 1998 "From Quendi and Eldar, Appendix D." Vinyar Tengwar 39, pp. 4–20.

- 1999 "Narqelion", Vinyar Tengwar 40, pp. 5–32

- 2000 "Etymological Notes: Osanwe-kenta" Vinyar Tengwar 41, pp. 5–6

- 2000 "From The Shibboleth of Fëanor" (written ca. 1968) Vinyar Tengwar 41, pp. 7–10 (A part of the Shibboleth of Fëanor was published in The Peoples of Middle-earth, pp. 331–366)

- 2000 "Notes on Óre" Vinyar Tengwar 41, pp. 11–19

- 2000 "Merin Sentence" Tyalie Tyalieva 14, p. 32–35

- 2001 "The Rivers and Beacon-hills of Gondor" (written 1967–1969) Vinyar Tengwar 42, pp. 5–31.

- 2001 "Essay on negation in Quenya" Vinyar Tengwar 42, pp. 33–34.

- 2001 "Goldogrim Pronominal Prefixes" Parma Eldalamberon 13 p. 97.

- 2001 "Early Noldorin Grammar", Parma Eldalamberon 13, pp. 119–132.

- 2002 "Words of Joy: Five Catholic Prayers in Quenya (Part One), Vinyar Tengwar 43:

- "Ataremma" (Pater Noster in Quenya) versions I–VI, p. 4–26

- "Aia María" (Ave Maria in Quenya) versions I–IV, pp. 26–36

- "Alcar i Ataren" (Gloria Patri in Quenya), pp. 36–38

- 2002 "Words of Joy: Five Catholic Prayers in Quenya (Part Two), Vinyar Tengwar 44:

- "Litany of Loreto" in Quenya, pp. 11–20.

- "Ortírielyanna" (Sub tuum praesidium in Quenya), pp. 5–11

- "Alcar mi tarmenel na Erun" (Gloria in Excelsis Deo in Quenya), pp. 31–38.

- "Ae Adar Nín" (Pater Noster in Sindarin) Vinyar Tengwar 44, pp. 21–30.

- 2003 "Early Qenya Fragments", Parma Eldalamberon 14.

- 2003 "Early Qenya Grammar", Parma Eldalamberon 14.

- 2003 "The Valmaric Scripts", Parma Eldalamberon 14.

- 2004 "Sí Qente Feanor and Other Elvish Writings", ed. Smith, Gilson, Wynne, and Welden, Parma Eldalamberon 15.

- 2005 "Eldarin Hands, Fingers & Numerals (Part One)." Edited by Patrick H. Wynne. Vinyar Tengwar 47, pp. 3–43.

- 2005 "Eldarin Hands, Fingers & Numerals (Part Two)." Edited by Patrick H. Wynne. Vinyar Tengwar 48, pp. 4–34.

- 2006 "Pre-Fëanorian Alphabets", Part 1, ed. Smith, Parma Eldalamberon 16.

- 2006 "Early Elvish Poetry: Oilima Markirya, Nieninqe and Earendel", ed. Gilson, Welden, and Hostetter, Parma Eldalamberon 16

- 2006 "Qenya Declensions", "Qenya Conjugations", "Qenya Word-lists", ed. Gilson, Hostetter, Wynne, Parma Eldalamberon 16

- 2007 "Eldarin Hands, Fingers & Numerals (Part Three)." Edited by Patrick H. Wynne. Vinyar Tengwar 49, pp. 3–37.

- 2007 "Five Late Quenya Volitive Inscriptions." Vinyar Tengwar 49, pp. 38–58.

- 2007 "Ambidexters Sentence", Vinyar Tengwar 49

- 2007 "Words, Phrases and Passages in Various Tongues in The Lord of the Rings", edited by Gilson, Parma Eldalamberon 17.

- 2009 "Tengwesta Qenderinwa", ed. Gilson, Smith and Wynne, Parma Eldalamberon 18.

- 2009 "Pre-Fëanorian Alphabets, Part 2", Parma Eldalamberon 18.

- 2010 "Quenya Phonology", Parma Eldalamberon 19.

- 2010 "Comparative Tables", Parma Eldalamberon 19.

- 2010 "Outline of Phonetic Development", Parma Eldalamberon 19.

- 2010 "Outline of Phonology", Parma Eldalamberon 19.

- 2012 "The Quenya Alphabet", Parma Eldalamberon 20.

- 2013 "Qenya: Declension of Nouns", Parma Eldalamberon 21.

- 2013 "Primitive Quendian: Final Consonants", Parma Eldalamberon 21.

- 2013 "Common Eldarin: Noun Structure", Parma Eldalamberon 21.

- 2015 "The Fëanorian Alphabet, Part 1", Parma Eldalamberon 22.

- 2015 "Quenya Verb Structure", Parma Eldalamberon 22.

See also Douglas A. Anderson, Carl F. Hostetter: A Checklist, Tolkien Studies 4 (2007).

External links

- Elvish.org FAQ – Article by Carl F. Hostetter. Succinct citations of Tolkien's own views of the purpose, completeness and usability of his languages.

- The Elvish Linguistic Fellowship: Publishes the journals Parma Eldalamberon, Tengwestië, and Vinyar Tengwar