Nassau Agreement

The Nassau Agreement, concluded on 21 December 1962, was an agreement negotiated between President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, and Harold Macmillan, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, to end the Skybolt Crisis. A series of meetings between the two leaders over three days in the Bahamas followed Kennedy's announcement of his intention to cancel the Skybolt air-launched ballistic missile project. The US agreed to supply the UK with Polaris submarine-launched ballistic missiles for the UK Polaris programme.

Under an earlier agreement, the US had agreed to supply Skybolt missiles in return for allowing the establishment of a ballistic missile submarine base in the Holy Loch near Glasgow. The British Government had then cancelled the development of its medium-range ballistic missile, known as Blue Streak, leaving Skybolt as the basis of the UK's independent nuclear deterrent in the 1960s. Without Skybolt, the V-bombers of the Royal Air Force (RAF) were likely to have become obsolete through being unable to penetrate the improved air defences that the Soviet Union was expected to deploy by the 1970s.

At Nassau, Macmillan rejected Kennedy's other offers, and pressed him to supply the UK with Polaris missiles. These represented more advanced technology than Skybolt, and the US was not inclined to provide them except as part of a Multilateral Force within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Under the Nassau Agreement the US agreed to provide the UK with Polaris. The agreement stipulated that the UK's Polaris missiles would be assigned to NATO as part of a Multilateral Force, and could be used independently only when "supreme national interests" intervened.

The Nassau Agreement became the basis of the Polaris Sales Agreement, a treaty which was signed on 6 April 1963. Under this agreement, British nuclear warheads were fitted to Polaris missiles. As a result, responsibility for Britain's nuclear deterrent passed from the RAF to the Royal Navy. The President of France, Charles de Gaulle, cited Britain's dependence on the United States under the Nassau Agreement as one of the main reasons for his veto of Britain's application for admission to the European Economic Community (EEC) on 14 January 1963.

Background

British nuclear deterrent

During the early part of the Second World War, Britain had a nuclear weapons project, codenamed Tube Alloys.[1] At the Quebec Conference in August 1943, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill and the President of the United States, Franklin Roosevelt, signed the Quebec Agreement, which merged Tube Alloys with the American Manhattan Project to create a combined British, American and Canadian project.[2] The British Government trusted that the United States would continue to share nuclear technology, which it regarded as a joint discovery, after the war,[3] but the United States Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (McMahon Act) ended technical cooperation.[4]

Fearing a resurgence of United States isolationism, and Britain losing its great power status, the British Government restarted its own development effort,[5] now codenamed High Explosive Research.[6] The first British atomic bomb was tested in Operation Hurricane on 3 October 1952.[7][8] The subsequent British development of the hydrogen bomb, and a favourable international relations climate created by the Sputnik Crisis, led to the McMahon Act being amended in 1958, resulting in the restoration of the nuclear Special Relationship in the form of the 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement, which allowed Britain to acquire nuclear weapons systems from the United States.

Britain's nuclear weapons armament was initially based on free-fall bombs delivered by the V-bombers of the Royal Air Force (RAF). With the development of the hydrogen bomb, a nuclear strike on the UK could kill most of the population and disrupt or destroy the political and military chains of command. The UK therefore adopted a counterforce strategy, targeting the airbases from which bombers could launch attacks on the UK, and knocking them out before they could do so.[10]

The possibility of the manned bomber becoming obsolete by the late 1960s in the face of improved air defences was foreseen.[10] One solution was the development of long-range missiles. In 1953, the Assistant Chief of the Air Staff (Operational Requirements), Air Vice-Marshal Geoffrey Tuttle, requested a specification for a ballistic missile with 3,700-kilometre (2,000 nmi) range,[11] and work commenced at the Royal Aircraft Establishment in Farnborough later that year.[12] In April 1955, the Commander-in-Chief of RAF Bomber Command, Air Chief Marshal Sir George Mills expressed his dissatisfaction with the counterforce strategy, and argued for a countervalue one that targeted administration and population centres for their deterrent effect.[10]

At a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) meeting in Paris in December 1953, United States Secretary of Defense, Charles E. Wilson, raised the possibility of a joint medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) development programme. Talks were held in June 1954, resulting in the signing of an agreement on 12 August 1954.[13][11] The United Kingdom with United States support would develop an MRBM,[11][14] which was called Blue Streak.[13] It was initially estimated to cost £70 million (equivalent to £1.84 billion in 2019), with the United States paying 15 per cent. By 1958, the project was in trouble. Its deployment was still years away, but the United States was supplying American-built Thor intermediate-range ballistic missiles under Project Emily, and there were concerns about liquid fuelled Blue Streak's vulnerability to a pre-emptive nuclear strike.[16][17]

To extend the effectiveness and operational life of the V-bombers, an Operational Requirement (OR.1132), was issued on 3 September 1954 for an air-launched, rocket-propelled standoff missile with a range of 190 kilometres (100 nmi) that could be launched from a V-bomber. This became Blue Steel. The Ministry of Supply placed a development contract with Avro in March 1956, and it entered service in December 1962.[18] By this time it was anticipated that even with Blue Steel, the air defences of the Soviet Union would soon improve to the extent that V-bombers might find it difficult to attack their targets, and there were calls for the development of the Blue Steel Mark II with a range of at least 1,100 kilometres (600 nmi).[19] Despite the name, this was a whole new missile, and not a development of Mark I.[20] The Minister of Aviation, Duncan Sandys, insisted that priority be accorded to getting the Mark I into service,[19] and the Mark II was cancelled at the end of 1959.[20]

Skybolt

Confronted with the same problem, the United States Air Force (USAF) also attempted to extend the operational life of its strategic bombers by developing a stand off missile, the AGM-28 Hound Dog.[21] The first production model was delivered to the Strategic Air Command (SAC) in December 1959. It carried a 4-megatonne-of-TNT (17 PJ) W28 warhead, and had a range of 1,189 kilometres (642 nmi) at high level and 630 kilometres; 390 miles (340 nmi) at low level. Its circular error probable (CEP) of over 1.9 kilometres (1 nmi) at full range was considered acceptable for a warhead of this size. A Boeing B-52 Stratofortress could carry two, but the underslung Pratt & Whitney J52 engine precluded its carriage by bombers with less underwing clearance like the Convair B-58 Hustler and the North American XB-70 Valkyrie. It entered service in large numbers, with 593 in service by 1963. Numbers declined thereafter to 308 in 1976, but it remained in service until 1977, when it was replaced by the AGM-69 SRAM.[22] Despite its being superior in performance to Blue Steel, the British showed little interest in Hound Dog. It could not be carried by the Handley Page Victor, and there were doubts as to whether even the Avro Vulcan had sufficient ground clearance.[23]

Even as Hound Dog was entering service, the USAF was contemplating a successor. An Advanced Air to Surface Missile (AASM) that could carry a 0.5-to-1.0-megatonne-of-TNT (2.1 to 4.2 PJ) warhead with a range of 1,900 to 2,800 kilometres (1,000 to 1,500 nmi) and a CEP of 910 metres (3,000 ft). Such a missile would make manned bombers competitive with Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs). However, it would also require significant technological advances. The missile became the AGM-48 Skybolt. As costs rose and support diminished, the USAF decreased its specifications to carrying a warhead 1,100 to 1,900 kilometres (600 to 1,000 nmi) and a CEP of 2.8 kilometres (1.5 nmi). This was estimated to cost $893.6 million (equivalent to $6.36 billion in 2021). A May 1960 report to the chairman of the President's Science Advisory Committee (PSAC), George Kistiakowsky, the PSAC Missile Advisory Panel stated that it was unconvinced of the Skybolt's merits, as the new LGM-30 Minuteman ICBM would be able to perform the same missions at much lower cost. PSAC therefore recommended in December 1960 that Skybolt be cancelled forthwith. United States Secretary of Defense Thomas S. Gates, Jr., elected not to request further funding for it, but avoided cancellation by reprogramming $70 million (equivalent to $498 million in 2021)from the previous year's allocation.[24]

A crucial reason for Skybolt's survival was the support it garnered from Britain.[24] Blue Streak was cancelled on 24 February 1960, subject to an adequate replacement being procured from the US. An initial solution appeared to be Skybolt, which combined the range of Blue Streak with the mobile basing of the Blue Steel, and was small enough that two could be carried on the Vulcan bomber.[25] Armed with a British Red Snow warhead, this would improve the capability of the UK's V-bomber force, and extend its useful life into the late 1960s and early 1970s.[26] Like the USAF, the RAF was concerned that ballistic missiles could eventually replace manned bombers.[27]

An institutional challenge came from the United States Navy, which was developing a submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM), the UGM-27 Polaris. The US Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Arleigh Burke, kept the First Sea Lord, Lord Mountbatten, apprised of its development.[28] By moving the deterrent out to sea, Polaris offered the prospect of a deterrent that was invulnerable to a first strike, and thereby reduced the risk of a first strike on the British Isles, which would no longer be effective. It also had greater value as a deterrent, because retaliation could not be avoided. It would also restore the Royal Navy to its traditional role as the nation's first line of defence, although not everyone in the navy was on board with that idea.[29] The British Nuclear Deterrent Study Group (BNDSG) produced a study that argued that SLBM technology was as yet unproven, that Polaris would be expensive, and that given the time it would take to build the boats, it could not be deployed before the early 1970s.[30] The Cabinet Defence Committee approved the acquisition of Skybolt in February 1960.[31]

The Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, met with President Dwight Eisenhower at Camp David near Washington in March 1960, and secured permission to buy Skybolt without strings attached. In return, the Americans were given permission to base the US Navy's Polaris-equipped ballistic missile submarines at the Holy Loch in Scotland.[32] The financial arrangement was particularly favourable to Britain, as the US was charging only the unit cost of Skybolt, absorbing all the research and development costs.[26] Mountbatten was disappointed, as was Burke, who now had to face the possible survival of Skybolt at the Pentagon.[31] Exactly what was agreed with regard to Polaris was not clear; the Americans wanted any later offer of Polaris to be as part of a scheme for deployment of NATO MRBMs known as the Multilateral Force.[33] With the Skybolt agreement in hand, the Minister of Defence, Harold Watkinson, announced the cancellation of Blue Streak to the House of Commons on 13 April 1960.[25]

American concerns

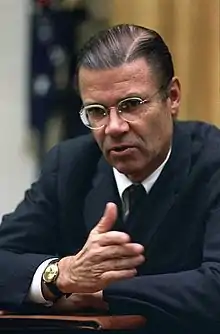

Skybolt proponents in the USAF hoped that the incoming Kennedy administration, which took office in January 1961, would be supportive of Skybolt, given its election campaigning on the basis of an alleged missile gap between Soviet and US capabilities.[34] Initially it was; Robert McNamara the new Secretary of Defense, defended Skybolt before the Senate Armed Services Committee.[35] He requested $347 million to purchase 92 Skybolt missiles in 1963, with the intention of deploying 1,150 missiles by 1967.[36] However, on 21 October 1961 the USAF raised its estimate of research and development costs to $492.6 million (equivalent to $3.51 billion in 2021), an increase of over $100 million (equivalent to $712 million in 2021), and production costs were now reckoned at $1.27 billion (equivalent to $9.04 billion in 2021), an increase of $591 million (equivalent to $4.21 billion in 2021).[37]

The Kennedy Administration adopted a policy of opposition to independent British nuclear forces in April 1961.[38] In a speech at Ann Arbor, Michigan, on 16 June 1962, McNamara stated "limited nuclear capabilities, operating independently, are dangerous, expensive, prone to obsolescence and lacking in credibility as a deterrent," and that "relatively weak national nuclear forces with enemy cities as their targets are not likely to perform even the function of deterrence."[39] The former United States Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, was even more blunt; in a speech at West Point he stated: "Britain's attempt to play a separate power role – that is, a role apart from Europe, a role based on a 'special relationship' with the United States, a role based on being the head of a Commonwealth which has no political structure or unity or strength and enjoys a fragile and precarious economic relationship – this role is about played out."[40]

The Kennedy administration was concerned that a situation like the Suez Crisis might repeat itself, one that would once again incite a nuclear threat against the UK from the Soviet Union.[41] The Americans developed a plan to force the UK into the Multilateral Force concept, a dual key arrangement that would allow launch only if both parties agreed. If nuclear weapons were part of a multinational force, attacking them would require attacks on the other hosting countries as well. The US feared that otherwise other countries would want to follow the UK lead and develop their own deterrent forces, leading to a nuclear proliferation problem even among their own allies. If a deterrent was provided by an international force, the need for individual forces would be reduced.[42][43]

Between 1955 and 1960, the British economy had lagged behind that of the rest of Europe, growing at an average of 2.5 per cent per annum, compared with France's growth of 4.8 per cent, Germany's of 6.4 per cent, and the European Economic Community (EEC) average of 5.3 per cent, and Macmillan devoted much of 1960 to laying the ground for Britain's entry into the EEC.[44] The US was concerned that providing Polaris to Britain would jeopardise Britain's prospects of joining the EEC.[45] Long-term US policy was to persuade the UK to build up its conventional military forces, and to secure admission to the EEC.[46]

McNamara introduced cost-effectiveness analysis to defence procurement. Skybolt suffered from rising costs,[43] and the first five test launches were failures. This was not unusual; Polaris and Minuteman had similar problems.[47] What doomed Skybolt was an inability to demonstrate capability beyond that achievable by Hound Dog, Minuteman or Polaris.[43] This meant that there were few advantages for the United States in continuing Skybolt,[48] but at the same time its cancellation would be a powerful political tool for bringing the UK into their Multilateral Force.[43] The British, on the other hand, had cancelled all other projects to concentrate fully on Skybolt. When warned not to put all their eggs in the one basket, the British replied that there was "no other egg, and no other basket".[48] On 7 November 1962, McNamara met with Kennedy, and recommended that Skybolt be cancelled. He then briefed the British Ambassador to the United States, David Ormsby-Gore. Kennedy agreed to cancel Skybolt on 23 November 1962.[47]

Negotiations

McNamara met with Solly Zuckerman, the UK Chief Scientific Adviser to the Ministry of Defence on 9 December, [49] and flew to London to meet with the Minister of Defence, Peter Thorneycroft, on 11 December.[50] On arrival he told the media that Skybolt was an expensive and complex program that had suffered five test failures.[51] Kennedy told a television interviewer that "we don't think that we are going to get $2.5 billion worth of national security".[52] US National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy gave an interview on television in which he stated that the US had no obligation to supply Skybolt to the UK.[53] Thorneycroft had expected McNamara to offer Polaris instead, but found him unwilling to countenance such an offer except as part of a Multinational Force. McNamara was willing to supply Hound Dog, or to allow the British to continue development of Skybolt.[50]

These discussions were reported to the House of Commons by Thorneycroft,[54] leading to a storm of protest. Air Commodore Sir Arthur Vere Harvey pointed out that while Skybolt had suffered five test failures, Polaris had thirteen failures in its development. He went on to state "that some of us on this side, who want to see Britain retain a nuclear deterrent, are highly suspicious of some of the American motives... and say that the British people are tired of being pushed around".[54] Liberal Party leader Jo Grimond asked: "Does not this mark the absolute failure of the policy of the independent deterrent? Is it not the case that everybody else in the world knew this, except the Conservative Party in this country? Is it not the case that the Americans gave up production of the B-52, which was to carry Skybolt, nine months ago?"[54]

As the Skybolt Crisis came to the boil in the UK, an emergency meeting between Macmillan and Kennedy was arranged to take place in Nassau, Bahamas. Accompanying Macmillan were British Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, Lord Home; Thorneycroft; Sandys; and Zuckerman. Naval expertise was supplied by Vice-Admiral Michael Le Fanu.[55] Ormsby-Gore flew to Nassau with Kennedy. En route, he brokered a deal whereby Britain and the United States would continue development of Skybolt, with each paying half the cost, the American half being a kind of termination fee.[56] In London, over one hundred Conservative members of Parliament, nearly one third of the parliamentary party, signed a motion urging Macmillan to ensure that Britain remained an independent nuclear power.[57]

Talks opened with Macmillan detailing the history of the Anglo-American Special Relationship, going back to the Second World War. He rejected the deal that Kennedy and Ormsby-Gore had reached. It would cost Britain about $100 million (equivalent to $712 million in 2021), and was not politically viable in the wake of recent public comments about Skybolt.[58] Kennedy then offered Hound Dog. Macmillan turned this down on technical grounds, although it had not been subjected to a detailed assessment, and probably would have worked for the RAF into the 1970s, as it did for the USAF.[59]

It therefore came down to Polaris, which the US did not wish to supply except as part of a Multinational Force. Macmillan was emphatic that he would commit the submarines to NATO only if they could be withdrawn in case of a national emergency. When pressed by Kennedy as to what sort of emergencies he had in mind, Macmillan mentioned the Soviet threats at the time of the Suez Crisis, Iraqi aggression against Kuwait, or a threat to Singapore. The British nuclear deterrent was not just for deterring attacks on the UK, but to underwrite Britain's role as a great power.[41] In the end, Kennedy did not wish to see Macmillan's government collapse,[60] which would imperil Britain's entry into the EEC,[61] so a face-saving compromise was found, which was released as a joint statement on 21 December 1962:

These forces, and at least equal US Forces, would be made available for inclusion in a NATO multilateral nuclear force. The Prime Minister made it clear that except where HMG [Her Majesty's Government] may decide that supreme national interests are at stake, these British forces will be used for the purposes of international defense of the Western Alliance in all circumstances.[62]

Canadian interlude

It was customary for the Canadians to be consulted when there was a meeting between the British and American leaders on the North American side of the Atlantic. This nicety was not observed when the Nassau conference was arranged,[63] but the Prime Minister of Canada, John Diefenbaker, invited Macmillan to a meeting in Ottawa. Macmillan countered with an offer to meet in Nassau after the Skybolt issue was resolved.[64] Kennedy and Diefenbaker loathed each other, and Kennedy made plans to leave early to avoid Diefenbaker,[63] but Macmillan persuaded Kennedy to stay for a lunch meeting.[64] Kennedy later described the uncomfortable meeting as being like "three whores at a christening".[63]

Nuclear weapons had become a political issue in Canada in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis, when Canadian Bomarc surface-to-air missiles had sat idly by while the country was threatened with a nuclear attack due to Diefenbaker's insistence that their nuclear warheads be stored outside Canada,[65] an arrangement which the Americans regarded as impractical.[66] Macmillan briefed Diefenbaker on the Nassau Agreement,[67] which Diefenbaker took to mean that manned bombers were now considered obsolete. This gave him further cause to continue to delay a decision on the Bomarc warheads, which were intended to shoot down bombers.[68] He did, however, express interest in Canadian participation in the Multilateral Force.[68][69]

Outcome

On 22 December, after the Nassau conference had ended, the USAF conducted the sixth and final test flight of Skybolt, having received explicit permission to do so from Roswell Gilpatric, the United States Deputy Secretary of Defense, in McNamara's absence. The test was a success.[51] Kennedy was furious, but Macmillan remained confident that the Americans had "determined to kill Skybolt on good general grounds—not merely to annoy us or drive Great Britain out of the nuclear business".[70] The successful test raised the possibility that the USAF might get the Skybolt project reinstated, and the Americans would renege on the Nassau Agreement.[70] This did not occur; Skybolt was officially cancelled on 31 December 1962.[51]

Macmillan placed the Nassau Agreement before the cabinet on 3 January 1963. He made the case for Britain retaining nuclear weapons. He asserted that it would not be in the best interest of the Western Alliance for all knowledge of the technology to reside with the United States; that possession of an independent nuclear capability gave Britain the ability to respond to threats from the Soviet Union even when the United States was not inclined to support Britain; and that possession of nuclear weapons gave Britain a voice in nuclear disarmament talks. However, concerns were expressed that the dependence on the United States would necessarily diminish Britain's influence on world affairs. Thorneycroft addressed the view that Britain should provide a nuclear deterrent from its own resources. He pointed out that Polaris represented $800 million (equivalent to $5.69 billion in 2021) in research and development costs that the United Kingdom would save. Nonetheless, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Selwyn Lloyd, was still concerned at the cost.[71]

_1986.JPEG.webp)

In the wake of the Nassau Agreement, the two governments negotiated the Polaris Sales Agreement, a treaty under the terms of which the US supplied Polaris missiles,[72] which was signed on 6 April 1963.[73] The missiles were equipped with British ET.317 warheads.[74][75][76] The UK retained its deterrent force, although its control passed from the RAF to the Royal Navy.[77] Polaris was a better weapon system for the UK's needs, and has been referred to as "almost the bargain of the century",[78] and an "amazing offer".[79] The V-bombers were immediately reassigned to NATO under the terms of the Nassau Agreement, carrying tactical nuclear weapons,[80] as were the Polaris submarines when they entered service in 1968.[81] The Polaris Sales Agreement was amended in 1980 to provide for the purchase of Trident.[82] British politicians did not like to talk about "dependence" on the United States, preferring to describe the Special Relationship as one of "interdependence".[83]

As had been feared, the President of France, Charles de Gaulle, vetoed Britain's application for admission to the EEC on 14 January 1963, citing the Nassau Agreement as one of the main reasons. He argued that Britain's dependence on United States through the purchase of Polaris rendered it unfit to be a member of the EEC.[84] The US policy of attempting to force Britain into their Multilateral Force proved to be a failure in light of this decision, and there was a lack of enthusiasm for it from the other NATO allies too. By 1965, the Multilateral Force was fading away. The NATO Nuclear Planning Group gave NATO members a voice in the planning process without full access to nuclear weapons. The Standing Naval Force Atlantic was established as a joint naval task force, to which various nations contributed ships rather than ships having mixed crews.[85]

In Canada, the Leader of the Opposition, Lester B. Pearson, came out strongly in favour of Canada accepting nuclear weapons. He encountered dissent from within his own Liberal Party, notably from Pierre Trudeau,[86] but opinion polls indicated that he was staking out a position held by the overwhelming majority of Canadians.[87][88] Nor was Diefenbaker's own Progressive Conservative Party united over the issue. On 3 February 1963, Douglas Harkness, the Minister of National Defence, submitted his resignation.[86] Two days later, Diefenbaker's government was toppled by a motion of no confidence in the House of Commons of Canada. An election followed, and Pearson became the Prime Minister on 8 April 1963.[89]

Macmillan's government lost a series of by-elections in 1962,[90] and was shaken by the Profumo affair in 1963.[91] In October 1963, on the eve of the annual Conservative Party Conference, Macmillan fell ill with what was initially feared to be inoperable prostate cancer.[92] His doctors assured him that it was benign, and that he would make a full recovery, but he took the opportunity to resign on the grounds of ill-health.[93] He was succeeded by Lord Home, who renounced his peerage and as Alec Douglas-Home campaigned on Britain's nuclear deterrent in the 1964 election.[94] While the issue was of low importance in the minds of the electorate, it was an issue on which Douglas-Home felt passionately, and on which the majority of voters supported his position.[95] The Labour Party election manifesto called for the Nassau Agreement to be renegotiated, and on 5 October 1964, the leader of the Labour Party, Harold Wilson, criticised the independent British deterrent as neither independent, nor British, nor a deterrent.[95] Douglas-Home narrowly lost the election to Wilson.[96] In office, Labour retained Polaris,[97] and assigned the Polaris boats to NATO, in accord with the Nassau Agreement.[98]

Kennedy, stung by the entire issue, commissioned a detailed report on the events and what lessons could be learned from them by Richard Neustadt, one of his advisors. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis recalled him reading the report and commenting that "If you want to know what my life is like, read this."[99] The report was declassified in 1992, and published as Report to JFK: The Skybolt Crisis in Perspective.[99]

Notes

- Gowing 1964, pp. 108–111.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 277.

- Goldberg 1964, p. 410.

- Gowing & Arnold 1974a, pp. 106–108.

- Gowing & Arnold 1974a, pp. 181–184.

- Cathcart 1995, pp. 23–24, 48, 57.

- Cathcart 1995, p. 253.

- Gowing & Arnold 1974b, pp. 493–495.

- Jones 2017, pp. 34–37.

- Boyes 2015, p. 34.

- Bayliss & Stoddart 2015, p. 255.

- Jones 2017, p. 37.

- Bayliss & Stoddart 2015, p. 98.

- Moore 2010, pp. 42–46.

- Young 2016, pp. 98–99.

- Wynn 1994, pp. 186–191.

- Wynn 1994, pp. 197–199.

- Moore 2010, p. 107.

- Roman 1995, p. 201.

- Werrell 1985, pp. 121–123.

- Young 2004, p. 626.

- Roman 1995, pp. 202–203.

- Moore 2010, pp. 47–48.

- Harrison 1982, p. 27.

- Cunningham 2010, pp. 104–105.

- Young 2002, pp. 67–68.

- Young 2002, p. 61.

- Jones 2017, pp. 178–182.

- Young 2002, p. 72.

- Moore 2010, pp. 64–68.

- Jones 2017, pp. 206–207.

- Roman 1995, p. 211.

- Roman 1995, p. 212.

- Roman 1995, p. 215.

- Kaplan, Landa & Drea 2006, p. 377.

- Moore 2010, p. 172.

- ""No Cities" Speech by Secretary of Defense McNamara". Atomic Archive. 9 July 1962. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- "Britain's role in world". The Guardian. 6 December 1962. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- Cunningham 2010, p. 328.

- Cunningham 2010, pp. 241–244.

- Harrison 1982, pp. 29–30.

- Cunningham 2010, p. 127.

- Cunningham 2010, pp. 316–317.

- Cunningham 2010, pp. 236–237.

- Moore 2010, pp. 168–169.

- Young 2004, p. 629.

- Cunningham 2010, p. 316.

- Moore 2010, p. 169.

- Roman 1995, p. 218.

- Cunningham 2010, p. 325.

- Jones 2017, p. 370.

- "Skybolt Missile (Talks)", Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), vol. 669, cc893-900, 17 December 1962

- Jones 2017, pp. 372–373.

- Cunningham 2010, pp. 324–325.

- Jones 2017, p. 371.

- Jones 2017, pp. 375–376.

- Young 2004, pp. 625–627.

- Harrison 1982, p. 30.

- Cunningham 2010, p. 321.

- "John F. Kennedy: Joint Statement Following Discussions With Prime Minister Macmillan – The Nassau Agreement". The American Presidency Project. 21 December 1962. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Bothwell 2007, p. 170.

- Maloney 2007, p. 294.

- Ghent 1979, p. 247.

- Ghent 1979, p. 257.

- "Chapter V - Nassau Meeting". Global Affairs Canada. 22 May 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Ghent 1979, pp. 259–260.

- Maloney 2007, pp. 309–310.

- Jones 2017, p. 392.

- Jones 2017, pp. 393–396.

- Priest 2005, pp. 355–360.

- Middeke 2000, p. 76.

- Moore 2010, pp. 196, 236–239.

- Jones 2017, pp. 413–415.

- Moore, Richard. "The Real Meaning of the Words: A Very Pedantic Guide to British Nuclear Weapons Codenames" (PDF). Mountbatten Centre for International Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2012.

- Cunningham 2010, p. 101.

- Dumbrell 2006, p. 174.

- Dawson & Rosecrance 1966, p. 42.

- Cunningham 2010, p. 356.

- Priest 2005, pp. 353–354.

- "US-UK Special Relationship". House of Commons – Foreign Affairs Committee. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Middeke 2000, pp. 69–70.

- Jones 2017, p. 420.

- Priest 2005, p. 788.

- Ghent 1979, pp. 256–257.

- Maloney 2007, p. 297.

- Bothwell 2007, pp. 171–172.

- Maloney 2007, pp. 302–303.

- Cunningham 2010, p. 344.

- Jones 2017, p. 507.

- "After Profumo: Tories in turmoil". The Courier. 29 September 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Lexden 2013, pp. 37–38.

- Epstein 1966, pp. 148–150.

- Epstein 1966, pp. 158–162.

- Moore 2010, p. 193.

- Stoddart 2012, pp. 21–24.

- Stoddart 2012, pp. 121–124.

- Avella 2001, p. 756.

References

- Avella, Jay (Winter 2001). "Book Review, Report to JFK: The Skybolt Crisis in Perspective". Rhetoric & Public Affairs. 4 (4): 756–757. doi:10.1353/rap.2001.0059. S2CID 177358399.

- Bayliss, John; Stoddart, Kristan (2015). The British Nuclear Experience: The Role of Beliefs, Culture, and Identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870202-3. OCLC 861979328.

- Bothwell, Robert (2007). Alliance and Illusion: Canada and the World, 1945-1984. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-1368-6. OCLC 1001160353.

- Boyes, John (2015). Thor Ballistic Missile: The United States and the United Kingdom in Partnership. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Fonthill Media. ISBN 978-1-78155-481-4. OCLC 921523156.

- Cathcart, Brian (1995). Test of Greatness: Britain's Struggle for the Atom Bomb. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5225-0. OCLC 31241690.

- Cunningham, Jack (2010). Nuclear Sharing and Nuclear Crises: A Study in Anglo-American Relations 1957–1963 (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Toronto. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- Dawson, R.; Rosecrance, R. (1966). "Theory and Reality in the Anglo-American Alliance". World Politics. 19 (1): 21–51. doi:10.2307/2009841. JSTOR 2009841. S2CID 155057300.

- Dumbrell, John (2006). A Special Relationship: Anglo-American relations from the Cold War to Iraq. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-8774-7. OCLC 433341082.

- Epstein, Leon D. (May 1966). "The Nuclear Deterrent and the British Election of 1964". Journal of British Studies. 5 (2): 139–163. doi:10.1086/385523. JSTOR 175321. S2CID 143866870.

- Ghent, Jocelyn Maynard (April 1979). "Did He Fall or Was He Pushed? The Kennedy Administration and the Collapse of the Diefenbaker Government". The International History Review. 1 (2): 246–270. doi:10.1080/07075332.1979.9640184. ISSN 0707-5332. JSTOR 40105730.

- Goldberg, Alfred (July 1964). "The Atomic Origins of the British Nuclear Deterrent". International Affairs. 40 (3): 409–429. doi:10.2307/2610825. JSTOR 2610825.

- Gowing, Margaret (1964). Britain and Atomic Energy 1939–1945. London: Macmillan. OCLC 3195209.

- Gowing, Margaret; Arnold, Lorna (1974a). Independence and Deterrence: Britain and Atomic Energy, 1945–1952, Volume 1, Policy Making. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-15781-7. OCLC 611555258.

- Gowing, Margaret; Arnold, Lorna (1974b). Independence and Deterrence: Britain and Atomic Energy, 1945–1952, Volume 2, Policy and Execution. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-16695-6. OCLC 946341039.

- Harrison, Kevin (1982). "From Independence to Dependence: Blue Streak, Skybolt, Nassau and Polaris". The RUSI Journal. 127 (4): 25–31. doi:10.1080/03071848208523423. ISSN 0307-1847.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Anderson, Oscar E. (1962). The New World, 1939–1946 (PDF). University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07186-5. OCLC 637004643. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Jones, Matthew (2017). Volume I: From the V-Bomber Era to the Arrival Of Polaris, 1945–1964. The Official History of the UK Strategic Nuclear Deterrent. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-67493-6. OCLC 1005663721.

- Kaplan, Lawrence S.; Landa, Ronald D.; Drea, Edward J. (2006). The McNamara Ascendancy 1961-1965 (PDF). History of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, volume 5. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary of Defense. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- Lexden, Lord (11 October 2013). "A Conference to Remember" (PDF). The House Magazine. pp. 36–39. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Maloney, Sean M. (2007). Learning to Love the Bomb: Canada's Nuclear Weapons During the Cold War. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-57488-616-0. OCLC 868549956.

- Middeke, Michael (Spring 2000). "Anglo-American Nuclear Weapons Cooperation After Nassau". Journal of Cold War Studies. 2 (2): 69–96. doi:10.1162/15203970051032318. ISSN 1520-3972. S2CID 57562517. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- Moore, Richard (2010). Nuclear Illusion, Nuclear Reality: Britain, the United States and Nuclear Weapons 1958–64. Nuclear Weapons and International Security since 1945. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-230-21775-1. OCLC 705646392.

- Navias, Martin S. (1991). British Weapons and Strategic Planning, 1955–1958. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-827754-5. OCLC 22506593.

- Priest, Andrew (July 2005). "'In Common Cause': The NATO Multilateral Force and the Mixed-Manning Demonstration on the USS Claude V. Ricketts, 1964–1965". The Journal of Military History. 69 (3): 759–789. doi:10.1353/jmh.2005.0182. JSTOR 3397118. S2CID 159619266.

- Roman, Peter J. (1995). "Strategic Bombers over the Missile Horizon, 1957–1963". Journal of Strategic Studies. 18 (1): 198–236. doi:10.1080/01402399508437584. ISSN 0140-2390.

- Stoddart, Kristan (2012). Losing an Empire and Finding a Role: Britain, the USA, NATO and Nuclear Weapons, 1964–70. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-33656-2. OCLC 951512907.

- Werrell, Kenneth P. (1985). The Evolution of the Cruise Missile (PDF). Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air University Press. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- Wynn, Humphrey (1994). RAF Strategic Nuclear Deterrent Forces, Their Origins, Roles and Deployment, 1946–1969. A documentary history. London: The Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-11-772833-2.

- Young, Ken (2002). "The Royal Navy's Polaris Lobby: 1955–62". Journal of Strategic Studies. 25 (3): 56–86. doi:10.1080/01402390412331302775. ISSN 0140-2390. S2CID 154124838.

- Young, Ken (2004). "The Skybolt Crisis of 1962: Mischief or Muddle?". Journal of Strategic Studies. 27 (4): 614–635. doi:10.1080/1362369042000314538. ISSN 0140-2390. S2CID 154238545.

- Young, Ken (2016). The American Bomb in Britain: US Air Forces' Strategic Presence 1946–64. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-8675-5. OCLC 942707047.

Further reading

- Neustadt, Richard (1999). Report to JFK: The Skybolt Crisis in Perspective. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801436222. OCLC 461377602.