National Postsecondary Student Aid Study

The National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS) is a study conducted every four years by the National Center for Education Statistics,[1] a division of the Institute of Education Sciences in the U.S. Department of Education. This study captures data regarding how students pay for postsecondary education, with special attention to how families fund higher education.[2] The NPSAS, which has been conducted periodically since 1987, has a complex design, utilizing sampling and weighting to achieve a sample that represents college students nationwide.[3][4]

Survey content

The NPSAS collects data from a variety of sources:

- Institutional student records are collected for each student enrolled in the study. These include student information such as major, admission test scores, grades, and financial data as well as institutional information such as the cost of tuition and institution type.[5]

- Student interviews ask about such things as language spoken in participants' childhood homes, expenses while attending college, employment, race/ethnicity.[6][7]

- Parents are surveyed regarding topics such as marital status, income, age, occupation, and the types of financing used to pay for their child's postsecondary education.[8]

- Financial Aid (FAFSA) records are collected from the National Student Loan Data System (NSLDS). This data contains information about financial need (in the form of expected family contributions), loans granted, total debt, and repayment status.[8][9]

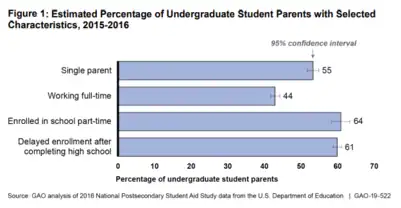

In addition, an element called the non-traditional student risk index is calculated using risk factors for dropping out of college. This index includes factors that have been correlated with low persistence such as working full-time, being a single parent, and being enrolled part-time.[10]

Use of NPSAS data in research

Aggregate NPSAS data is made available to the public via the Department of Education's website. Data containing personally identifiable information is only available to researchers who apply for and obtain a restricted use license from the Department of Education.[8]

NPSAS data is used by researchers to identify trends, for example in student loan repayments and the demographics of postsecondary students.[11] This trend data is used in a variety of ways, for example identifying best practices in decreasing inequalities in higher education[12][13] and means of increasing student persistence.[14][15]

Selected examples of NPSAS data research include:

- A 2019 Pew Research Center report identified a rise in student poverty, particularly at less selective institutions.[16]

- An article published in the 2019 volume of the journal Educational Researcher, which discusses the differences in student borrowing across race and ethnicity.[17]

- An Urban Institute report published in 2022 studying the impacts of inflation and financial aid borrowing limits on postsecondary students.[18]

- A 2022 article in the journal Harvard Educational Review outlines the impact of the post-9/11 GI bill on the college choices of Veterans.[19]

Trends

One of the most significant trends identified by studies of NPSAS data is the rise of nontraditional undergraduate students enrolled in higher education. The term "nontraditional student" refers to a student with one or more of the following characteristics:

- Considered independent when applying for federal financial aid (FAFSA)

- Having one or more dependent children

- Not having a high school diploma

- Delayed enrollment in higher education

- Being employed full-time[20]

Some researchers also use being over the age of 24 at the start of enrollment as a non-traditional characteristic, although this is one of the criteria for FAFSA independent status. The rise in nontraditional students enrolled in colleges and universities was first brought to light by Susan Choy, who published a study in 2002 finding that 73% of college students had at least one non-traditional characteristic during the 1999–2000 school year.[21] This finding prompted postsecondary institutional leaders to reassess student needs[22] and to a review of policies related to financial aid.[23]

A 2011 follow-up study using 2007-2008 NPSAS data found a similar percentage of nontraditional learners (70%) and identified several key segments of college students that overlapped with this group.[7]

- Working learners are students employed while attending school, with those who worked at least 40 hours per week being more likely to attend college part-time and/or to be financially independent than non-working students

- Service member learners includes those with active, reserve, and veteran status. These students are automatically considered financially independent and were more likely to attend college part-time

- Single parent learners are also all financially independent for FAFSA. This group was more likely to attend school part-time and to work 26 hours per week or more

- Minority learners includes college students who are Black/African-American, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian, Native Hawaiian, or who have multiple racial identities. A large proportion of these students (70%-85%) indicated working at least part-time while attending college

Criticisms of the NPSAS

The most recently released full NPSAS data set is from 2015 to 2016,[24] nearly seven years out-of-date at the time of this writing, and researchers have emphasized the importance of a more timely release of data, especially given the turbulence of higher education policy.[7]

Researchers have also critiqued the level of aggregation of NPSAS data sets made available without expensive and difficult-to-obtain restricted data use licenses, and have commented on limitations of the PowerStats online data analysis tool to group students by multiple variables and to create new variables.[25]

Others have found that useful variables are not included in the NPSAS, for example the status of tax return filings[18] and high school grades.[26] Another criticism is that the data collection cycle necessarily discounts students who drop out early in their studies or who enroll in a semester other than Fall.[26] Similarly, Pell Grant data is not available by semester, making it difficult to calculate eligibility for part-time students.[27] At other times, the differences in data collection between the NPSAS and other government entities makes it difficult to make direct comparisons.[28]

References

- "National Postsecondary Student Aid Study". RTI. 2017-03-14. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- Addo, Fenaba R. (2017). Ensuring a More Equitable Future: Exploring and Measuring the Relationship Between Family Wealth, Education Debt, and Wealth Accumulation (PDF). Postsecondary Value Commission.

- Mitchell, Travis (2019-05-22). "A Rising Share of Undergraduates Are From Poor Families, Especially at Less Selective Colleges". Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- Kofoed, Michael S. (2017-02-01). "To Apply or Not to Apply: FAFSA Completion and Financial Aid Gaps". Research in Higher Education. 58 (1): 1–39. doi:10.1007/s11162-016-9418-y. ISSN 1573-188X. S2CID 254990855.

- Skira, Aaron Michael (2018). Consequences of Postsecondary Education Institution Policies and Practices: A Structural Model of Tuition Costs, Student Financial Aid, Selectivity, Proximity, and Enrolled Undergraduate Students' Aggregate Capital (Dissertation).

- Murphy, Kevin B. (2004). "Identifying Additional Layers of Diversity at Public Urban Universities by Using Data from the 2000 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study". Metropolitan Universities. 15 (4): 23–37.

- Reeves, Tamara J.; Miller, Leslie A.; Rouse, Ruby A. (2011). Reality Check: A Vital Update to the Landmark 2002 NCES Study of Nontraditional College Students (PDF). Apollo Research Institute.

- White, Paul M. (2007). Assessing the Factors that Affect the Persistence and Graduation Rates of Native American Students in Postsecondary Education (Dissertation). Bowling Green State University.

- Cadena, Brian C.; Keys, Benjamin J. (2013). "Can Self-Control Explain Avoiding Free Money? Evidence from Interest-Free Student Loans". The Review of Economics and Statistics. 95 (4): 1117–1129. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00321. ISSN 0034-6535. JSTOR 43554817. PMC 4021586. PMID 24839312.

- Wladis, Claire; Hachey, Alyse C.; Conway, Katherine M. (2015). "The Representation of Minority, Female, and Non-Traditional STEM Majors in the Online Environment at Community Colleges: A Nationally Representative Study". Community College Review. 43 (1): 89–114. doi:10.1177/0091552114555904. S2CID 147497596.

- Scott-Clayton, Judith (2018-01-11). "The Looming Student Loan Default Crisis is Worse than we Thought". Brookings. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- Herbaut, Estelle; Geven, Koen (2020-02-01). "What works to reduce inequalities in higher education? A systematic review of the (quasi-)experimental literature on outreach and financial aid". Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. Experimental methods in social stratification research. 65: 100442. doi:10.1016/j.rssm.2019.100442. ISSN 0276-5624.

- Kelchen, Robert (2019). "Exploring the Relationship Between Performance-Based Funding Design and Underrepresented Student Enrollment at Community Colleges". Community College Review. 47 (4): 382–405. doi:10.1177/0091552119865611. ISSN 0091-5521. S2CID 201392053.

- Castleman, Benjamin L.; Page, Lindsay C. (2015-07-01). "Summer nudging: Can personalized text messages and peer mentor outreach increase college going among low-income high school graduates?". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. Behavioral Economics of Education. 115: 144–160. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2014.12.008. ISSN 0167-2681.

- Castleman, Benjamin L.; Page, Lindsay C. (2016). "Freshman Year Financial Aid Nudges: An Experiment to Increase FAFSA Renewal and College Persistence". The Journal of Human Resources. 51 (2): 389–415. doi:10.3368/jhr.51.2.0614-6458R. ISSN 0022-166X. JSTOR 24736027. S2CID 155814000.

- Fry, Richard; Cilluffo, Anthony (2019). "A Rising Share of Undergraduates are From Poor Families, Especially at Less Selective Colleges" (PDF). Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- Chan, Monnica; Kwon, Jihye; Nguyen, David J.; Saunders, Katherine M.; Shah, Nilkamal; Smith, Katie N. (2019). "Indebted Over Time: Racial Differences in Student Borrowing". Educational Researcher. 48 (8): 558–563. doi:10.3102/0013189X19864969. ISSN 0013-189X. S2CID 200039771.

- Delisle, Jason; Blagg, Kristin (2022). "Federal Undergraduate Loan Limits and Inflation: What Borrowing Patterns and Evidence Reveal about Current Policy" (PDF). Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- Zhang, Liang (2022). "How Did the Post-9/11 GI Bill Affect Veteran Students' Undergraduate College Choices? An Application of Propensity Scores in Difference-in-Differences Models". Harvard Educational Review. 92 (1): 1–31. doi:10.17763/1943-5045-92.1.1. S2CID 247991353.

- Radford, Alexandria Walton; Cominole, Melissa; Skomsvold, Paul (2015). "Demographic and Enrollment Characteristics of Nontraditional Undergraduates: 2011-12. Web Tables. NCES 2015-025" (PDF). Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- Choy, Susan (2002). "Nontraditional Undergraduates, NCES 2009-012" (PDF). Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- Hines, Mary (2009). "Serving Adult Students: Challenges and Committments" (PDF). Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- Nicholas, S. (2008). "Nontraditional Older Students". EBSCO Researcher Starter. 1 (7).

- Delisle, Jason (2020). "Evidence Against the Free-College Agenda: An Analysis of Prices, Financial Aid, and Affordability at Public Universities" (PDF). Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality (2021). "Obstacles to Opportunity: Accompanying Methodology Note" (PDF). Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- St. John, Edward P.; Starkey, Johnny B.; Paulsen, Michael B.; Mbaduagha, Loretta A. (1995). "The Influence of Prices and Price Subsidies on Within-Year Persistence by Students in Proprietary Schools". Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 17 (2): 149–165. doi:10.3102/01623737017002149. JSTOR 1164558. S2CID 145592780.

- Dynarski, Susan; Scott-Clayton, Judith; Wiederspan, Mark (2013). "Simplifying Tax Incentives and Aid for College: Progress and Prospects". Tax Policy and the Economy. 27 (1): 161–202. doi:10.1086/671247. ISSN 0892-8649. S2CID 154841134.

- "Publication of the National Center on Secondary Education and Transition". www.ncset.org. Retrieved 2023-04-12.