Irish National War Memorial Gardens

The Irish National War Memorial Gardens (Irish: Gairdíní Náisiúnta Cuimhneacháin Cogaidh na hÉireann) is an Irish war memorial in Islandbridge, Dublin, dedicated "to the memory of the 49,400 Irish soldiers who gave their lives in the Great War, 1914–1918",[1] out of a total of 206,000 Irishmen who served in the British forces alone during the war.[2]

with view of one of the pairs of granite bookrooms

in side view, showing one of four granite bookrooms

The Memorial Gardens also commemorate all other Irish men and women who at that time served, fought and died in Irish regiments of the Allied armies, the British, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, South African and United States armies in support of the Triple Entente's war effort against the Central Powers.

Background

In 1914, Ireland was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and many Irishmen joined the British armed forces. In particular, the British Army had eight regiments that were raised in Ireland.[3]

Commissioning

Following a meeting of over 100 representatives from all parts of Ireland on 17 July 1919, a trust fund was created to consider plans and designs for a permanent memorial "to commemorate all those Irish men and women killed in the First World War".[1] A general committee was formed in November 1924 to pursue proposals for a site in Dublin. For technical and administrative reasons it was not until its meeting on 28 March 1927 in the Shelbourne Hotel that Merrion Square, alternatively St Stephen's Green, were proposed. A debate in the Free State Senate failed to resolve the impasse. W. T. Cosgrave, president of the Irish Free State Executive Council then appointed Cecil Lavery to set up a "War Memorial Committee" to advance the memorial process. [4]

Cosgrave who was very interested in bringing the memorial to fruition met with Andrew Jameson, a senator and member of the committee on 9 December 1930 and suggested the present site. At that time known as the "Longmeadows Estates" it is about 60 acres (24 ha) in extent stretching parallel along the south bank of the River Liffey from Islandbridge towards Chapelizod.[1] His proposal was adopted by the committee on 16 December 1931. Cosgrave said at the time that ". ... this is a big question of remembrance and honour to the dead and it must always be a matter of interest to the head of the government to see that a project so dear to a big section of the citizens should be a success". [4]

General Sir William Hickie saying "the memorial is an all-Ireland one". A generous gift was sanctioned by the Irish Government in an eleven paragraph agreement with the committee on 12 December 1933, the Dublin City Council Office of Public Works (OPW) having already commenced work with 164 men during 1932. [4]

In the adverse political conditions of the 1930s, Éamon de Valera's government still recognised the motives of the memorial and made valuable state contributions to it. The cabinet approved work be divided 50% between British and Irish WWI ex-servicemen. [4] Many difficulties arose in 1937 for the committee with regard to plants, trees and the need to obtain a completion certificate from the Office of Public Works, which was finally issued in January 1938. [4] An official opening was agreed for 30 July 1939, but the looming threat of war led to it being postponed. In the end, no official opening ever happened, but the first public event in the gardens took place in 1940 for Armistice Day celebrations.[5]

Design

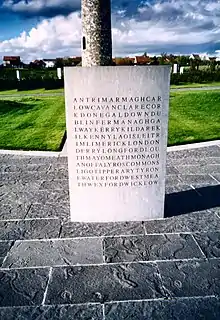

Designed by the great memorialist Sir Edwin Lutyens who had already landscaped designed several sites in Ireland and around Europe, it is outstanding among the many war memorials he created throughout the world.[1] He found it a glorious site. The sunken Garden of Remembrance surrounds a Stone of Remembrance of Irish granite symbolising an altar, which weighs seven and a half tons. The dimensions of this are identical to First World War memorials found throughout the world, and is aligned with the Great Cross and central avenue.[1] Opposite to the Phoenix Park obelisk, it lies about three kilometres from the centre of Dublin, on grounds which gradually slope upwards towards Kilmainham Hill. Old chronicles describe Kilmainham Hill as the camping place of Brian Boru and his army prior to the last decisive Battle of Clontarf on 23 April 1014. The memorial was amongst the last to be erected to the memory of those who sacrificed their lives in World War I (Canada's National War Memorial was opened in 1939), and is "the symbol of Remembrance in memory of a Nation's sacrifice".[6] The elaborate layout includes a central sunken rose garden composed by a committee of eminent horticulturalists, various terraces, pergolas, lawns and avenues lined with impressive parkland trees, and two pairs of bookrooms in granite, representing the four provinces of Ireland, and containing illuminated volumes recording the names of all the dead.[1]

At the north of the gardens overlooking the River Liffey stands a domed temple. This also marks the beginning of the avenue leading gently upwards to the steps containing the Stone of Remembrance. On the floor of the temple are an extract from the "War Sonnett II: Safety" by Rupert Brooke:

"We have found safety with all things undying,

The winds, and morning, tears of men and mirth,

The deep night, and birds singing, and clouds flying,

And sleep, and freedom, and the autumnal earth."

Construction

There was no discord in its building – workers were so drawn from the unemployed that 50 per cent were former World War I ex-British Army and 50 per cent ex-Irish Army men. To provide as much work as possible the use of mechanical equipment was restricted, and even granite blocks of 7 and 8 tonnes from Ballyknocken and Donnelly's quarry Barnaculla were manhandled into place with primitive tackles of poles and ropes. On completion and intended opening in 1939 (which was postponed) the trustees responsible said: "It is with a spirit of confidence that we commit this noble memorial of Irish valour to the care and custody of the Government of Ireland".[7]

Dedication, neglect and renewal

Although commemorations by Irish British Armed Forces veterans and families of those killed in the course of the Great War took place at the site for a few years in the late 1940s and 1950s, with some large attendances,[8] the politico-cultural situation in the state, and its nationally dominant ideologically adverse view of Ireland's role in World War I, and of those who had volunteered to fight in World War II, prevented the garden from being civically opened and dedicated.

The garden was subject to two Irish Republican paramilitary attacks. On Christmas night 1956 a bomb was placed at the base of its Stone of Remembrance and memorial cross and detonated, but the County Wicklow quarried granite withstood the blast with little damage. Another attempt was made to bring it down again with a bomb detonation in October 1958, which once more failed, resulting in superficial damage.[9]

A subsequent lack of financing from the government to provision its up-keep and care allowed the site to fall into dilapidation and vandalism over the following decades, to the point that by the late 1970s it had become a site for caravans and animals of the Irish Traveller community, with the Dublin Corporation's refuse disposal office using it as a rubbish dump for the city's waste.[10] In addition fifty years of storms and the elements had left their mark, with structural damage unrepaired to parts of the garden's ornamentation.

In the mid-1980s economic and cultural shifts began to occur in Ireland which facilitated a regeneration of urban decay in Dublin, and the beginning of a change in the public's view of its pre-Irish Revolution national history and identity, which led to a project of restoration work to renew the park and gardens to their former splendour being undertaken by the Office of Public Works, co-funded by the National War Memorial Committee. On 10 September 1988 the fully restored gardens were re-opened to the public, and formally dedicated by representatives of the four main churches of Ireland, half a century after its creation.

Official ceremonial events at the garden

- A state commemoration to mark the 90th anniversary of the Battle of the Somme on 1 July 2006 was attended by the President of Ireland Mary McAleese, the Taoiseach Bertie Ahern, members of the Oireachtas, leading representatives of all political parties in Ireland, the Diplomatic Corps of the Allies of World War I, delegates from Ulster, representatives of the four main churches, and accompanied by a guard of honour of the Irish Army and Army Band.

- On the 18 May 2011 Queen Elizabeth II and the President of Ireland, Mary McAleese, laid wreaths to honour Ireland's dead of World War I and World War II at a ceremony in the garden during the first state visit of a British monarch to the Irish Republic.[11]

- On the 9 July 2016 a state ceremony to mark the centenary of the Battle of the Somme took place within the gardens, with the Taoiseach Enda Kenny in attendance and the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, laying a wreath to the honour of the soldiers of Ireland who lost their lives during its course.[12]

Roll of Honour

In the granite paved pergolas surrounding the garden are the 8 illuminated volumes of Ireland's Memorial Records 1914-1918 which record the names of the dead. Each page of is illustrated on four sides with artwork by Harry Clarke. They are displayed in cases designed by Lutyens.[13]

A wooden cross of oak, the Ginchy Cross, built by the 16th (Irish) Division and originally erected on the Somme to commemorate 4,354 men of the 16th who died in two engagements, is housed in the same building. Three granite replicas of this cross are erected at locations liberated by Irish divisions – Guillemont and Messines-Wytschaete in Belgium, and Thessaloniki in Greece.

Patronage

The Irish National War Memorial Gardens are now managed by the Government's Office of Public Works (OPW) in conjunction with the National War Memorial Committee.

A further Great War Irish national memorial, taking the form of an all-Ireland journey of conciliation, was jointly opened in 1998 by Mary McAleese, President of Ireland, Queen Elizabeth II and Albert II, King of the Belgians at the Island of Ireland Peace Park, Messines, Flanders, Belgium.

Creosote stream

A small stream, commonly known as the Creosote Stream, emerges and flows into the River Liffey at the western edge of the gardens. The stream rises west of Inchicore railway works, some distance away, before flowing underneath the site to emerge close to the Liffey on the grounds of the War Memorial Gardens. The stream got its name from pollutants which used to leach into it from the railway works.[14][15]

See also

- List of works by Edwin Lutyens

- Garden of Remembrance, Dublin

- Peace Park, Dublin

- Grangegorman Military Cemetery, Dublin

- Other Great War memorials relating to Ireland:

- Island of Ireland Peace Park, Messines, Belgium.

- Menin Gate memorial, Ypres, Belgium.

- Ulster Tower Memorial, Thiepval, France.

Notes

- Dúchas The Heritage Service, Visitors Guide to the Gardens, from the Office of Public Works

- Fergus Campbell, Land and Revolution, Nationalist Politics in the West of Ireland 1891–1921, p. 196

- Johnson, pp. 16–17.

- HISTORY IRELAND publication History of the National War Memorial Gardens cit. ext-link

- "The Second World War | Dublin Commemorative Sites". Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- British Legion Annual, Irish Free State Souvenir Edition 1925–1935; National Library of Ireland, LO .

- Henry Edward D. Harris (Major) The Irish Regiments in the First World War, pp 210. Mercier Press Cork (1968), National Library of Ireland Dublin

- 'Come Here To Me, Dublin Life & Culture' 9 September 2013, online magazine article. https://comeheretome.com/2013/09/09/failed-attempts-on-the-war-memorial-gardens-islandbridge/

- 'Come Here To Me, Dublin Life & Culture' 9 September 2013, online magazine article, 'Failed Attempts on the War Garden, Islandbridge'. https://comeheretome.com/2013/09/09/failed-attempts-on-the-war-memorial-gardens-islandbridge/

- 'Ireland's Great War', by Kevin Myers (Pub. Lilliput Press, 2014).

- 'Sombre remembrance of the war dead in the hush of Islandbridge', 'Irish Times' 19 May 2011. http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/ireland/2011/0519/1224297286972.html

- 'Heroic dead of Ireland recalled at Somme commemoration', 'The Irish Times', 9 July 1916 http://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/heroic-dead-of-ireland-recalled-at-somme-commemoration-1.2716862

- Helmers, Marguerite (12 December 2015). "Harry Clarke's first World War". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- Doyle, p. 36.

- Oram, Hugh (23 October 2004). "Dublin once had a grand total of over 60 streams and rivers that flowed entirely above ground". The Irish Times. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

Bibliography

- Johnson, Nuala (2007) [2003]. Ireland, the Great War, and the Geography of Remembrance (reprinted ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521037051.

- Doyle, Joseph (2013). Ten Dozen Waters: The Rivers and Streams of County Dublin (8th ed.). Dublin: Rath Eanna Research. ISBN 9780956636379.

Further reading

- Kevin Myers: Ireland's Great War, Lilliput Press (2014), ISBN 9781843516354.

- Myles Dungan: They Shall not Grow Old: Irish Soldiers in the Great War, Four Courts Press (1997), ISBN 1-85182-347-6.

- Keith Jeffery: Ireland and the Great War, Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge (2000), ISBN 0-521-77323-7.

- Bryan Cooper (1918): The 10th (Irish) Division in Gallipoli, Irish Academic Press (1993), (2003). ISBN 0-7165-2517-8.

- Thomas P. Dooley: Irishmen or English Soldiers? : the Times of a Southern Catholic Irish Man (1876–1916), Liverpool Press (1995), ISBN 0-85323-600-3.

- Terence Denman: Ireland's unknown Soldiers: the 16th (Irish) Division in the Great War, Irish Academic Press (1992), (2003) ISBN 0-7165-2495-3.

- Desmond & Jean Bowen: Heroic Option: The Irish in the British Army, Pen & Sword Books (2005), ISBN 1-84415-152-2.

- Steven Moore: The Irish on the Somme (2005), ISBN 0-9549715-1-5.

- Thomas Bartlett & Keith Jeffery: A Military History of Ireland, Cambridge University Press (1996) (2006), ISBN 0-521-62989-6

- David Murphy: Irish Regiments in the World Wars, Osprey Publishing (2007), ISBN 978-1-84603-015-4

- David Murphy: The Irish Brigades, 1685–2006, A gazetteer of Irish Military Service past and present, Four Courts Press (2007)

The Military Heritage of Ireland Trust. ISBN 978-1-84682-080-9 - Stephen Walker: Forgotten Soldiers; The Irishmen shot at dawn Gill & Nacmillan (2007), ISBN 978-0-7171-4182-1

External links

- OPW Guide to Irish National War Memorial

- Access and other information from the Office of Public Works (OPW)

- Irish War Memorial Committee archives — held by Royal Dublin Fusiliers Association, online at Digital Repository of Ireland

- Department of the Taoiseach: Irish Soldiers in the First World War

- The Military Heritage of Ireland Trust

- The Irish War Memorials Project – listing of monuments throughout Ireland

- Dublin Memorials of the Great War 1914–1918

- Homepage of the Connaught Ranger's Association

- Homepage of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers Association

- Homepage of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers Association

- Homepage of the Royal Munster Fusilier's Association

- Homepage of the Waterford Museum: WWI and Ireland

- Homepage of the Bandon War Memorial Committee

- Homepage of the Combined Irish Regiments Association