National Natural Landmark

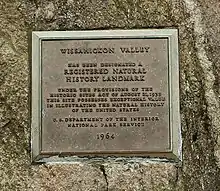

The National Natural Landmarks (NNL) Program recognizes and encourages the conservation of outstanding examples of the natural history of the United States.[1] It is the only national natural areas program that identifies and recognizes the best examples of biological and geological features in both public and private ownership. The program was established on May 18, 1962, by United States Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall.

The program aims to encourage and support voluntary preservation of sites that illustrate the geological and ecological history of the United States. It also hopes to strengthen the public's appreciation of the country's natural heritage. As of January 2021, 602 sites have been added to the National Registry of Natural Landmarks.[2] The registry includes nationally significant geological and ecological features in 48 states, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

The National Park Service administers the NNL Program and if requested, assists NNL owners and managers with the conservation of these important sites. Land acquisition by the federal government is not a goal of this program. National Natural Landmarks are nationally significant sites owned by a variety of land stewards, and their participation in this federal program is voluntary.

The legislative authority for the National Natural Landmarks Program stems from the Historic Sites Act of August 21, 1935 (49 Stat. 666, 16 U.S.C. 641); the program is governed by federal regulations.[3] The NNL Program does not have the protection features of Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. Thus, designation of a National Natural Landmark presently constitutes only an agreement with the owner to preserve, as far as possible, the significant natural values of the site or area. Administration and preservation of National Natural Landmarks is solely the owner's responsibility. Either party may terminate the agreement after they notify the other.

Designation

The NNL designation is made by the Secretary of the Interior after in-depth scientific study of a potential site. All new designations must have owner concurrence. The selection process is rigorous: to be considered for NNL status, a site must be one of the best examples of a natural region's characteristic biotic or geologic features. Since establishment of the NNL program, a multi-step process has been used to designate a site for NNL status. Since 1970, the following steps have constituted the process.

- A natural area inventory of a natural region is completed to identify the most promising sites.

- After landowners are notified that the site is being considered for NNL status, a detailed onsite evaluation is conducted by scientists other than those who conducted the inventory.[note 1]

- The evaluation report is peer-reviewed by other experts to assure its soundness.

- The report is reviewed further by National Park Service staff.

- The site is reviewed by the Secretary of the Interior's National Park Advisory Board to determine that the site qualifies as an NNL.

- The findings are provided to the Secretary of the Interior who approves or declines.

- Landowners are notified a third time informing them that the site has been designated an NNL.

Prospective sites for NNL designation are terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems; geological features, exposures, and landforms that record active geological processes or portions of earth history; and fossil evidence of biological evolution. Each major natural history "theme" can be further subdivided into various sub-themes. For example, sub-themes suggested in 1972 for the overall theme "Lakes and ponds" included large deep lakes, large shallow lakes, lakes of complex shape, crater lakes, kettle lake and potholes, oxbow lakes, dune lakes, sphagnum-bog lakes, lakes fed by thermal streams, tundra lakes and ponds, swamps and marshy areas, sinkhole lakes, unusually productive lakes, and lakes of high productivity and high clarity.

Ownership

The NNL program does not require designated properties to be owned by public entities. Lands under almost all forms of ownership or administration have been designated—federal, state, local, municipal, and private. Federal lands with NNLs include those administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, Bureau of Reclamation, Fish and Wildlife Service, Air Force, Marine Corps, Army Corps of Engineers, Navy, and others.

Some NNL have been designated on lands held by Native Americans or tribes. NNLs also have been designated on state lands that cover a variety of types and management, such as forest, park, game refuge, recreation area, and preserve. Private lands with NNLs include those owned by universities, museums, scientific societies, conservation organizations, land trusts, commercial interests, and private individuals. Approximately 52% of NNLs are administered by public agencies, more than 30% are entirely privately owned, and the remaining 18% are owned or administered by a mixture of public agencies and private owners.

Access

Participation in the NNL Program carries no requirements regarding public access. The NNL registry includes many sites of national significance that are open for public tours, but others are not. Since many NNLs are located on federal and state property, permission to visit is often unnecessary. Some private properties may be open to public visitation or just require permission from the site manager. On the other hand, some NNL private landowners desire no visitors whatsoever and might even prosecute trespassers. The reasons for this viewpoint vary: potential property damage or liability, fragile or dangerous resources, and desire for solitude or no publicity.

Property status

NNL designation is an agreement between the property owner and the federal government. NNL designation does not change ownership of the property nor induce any encumbrances on the property. NNL status does not transfer with changes in ownership.

Participation in the NNL Program involves a voluntary commitment on the part of the landowner(s) to retain the integrity of their NNL property as it was when designated. If "major" habitat or landscape destruction is planned, participation in the NNL Program by a landowner would be disingenuous and meaningless.

The federal action of designation imposes no new land use restrictions that were not in effect before the designation. It is conceivable that state or local governments of their own volition could initiate regulations or zoning that might apply to an NNL. However, as of 2005 no examples of such a situation have been identified. Some states require planners to ascertain the location of NNLs.

List of landmarks

Listed by state or territory in alphabetical order. As of January 2021, there were 602 listings.[2]

| State or territory | Number of landmarks | Number, non-duplicated | Earliest declared | Latest declared | Image | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alabama | 7 | 7 | October 1971 | November 1987 |  |

| 2 | Alaska | 16 | 16 | 1967 | 1976 |  |

| 3 | American Samoa | 7 | 7 | 1972 | 1972 |  |

| 4 | Arizona | 10 | 10 | 1965 | 2011 |  |

| 5 | Arkansas | 5 | 5 | 1972 | 1976 | .JPG.webp) |

| 6 | California | 37 | 37 | 1964 | January 2021 |  |

| 7 | Colorado | 16 | 15 [note 2] | 1964 | January 2021 |  |

| 8 | Connecticut | 8 | 7[note 3] | April 1968 | November 1973 | _-_prints.JPG.webp) |

| 9 | Delaware | 0 | ||||

| 10 | Florida | 18 | 18 | March 1964 | May 1987 |  |

| 11 | Georgia | 11 | 11 | 1966 | April 2013 |  |

| 12 | Guam | 4 | 4 | 1972 | 1972 | _in_Guam_in_June_2017.jpg.webp) |

| 13 | Hawaii | 7 | 7 | June 1971 | December 1972 |  |

| 14 | Idaho | 11 | 11 | 1968 | 1980 |  |

| 15 | Illinois | 18 | 18 | 1965 | 1987 |  |

| 16 | Indiana | 30 | 29 [note 4] | 1965 | 1986 |  |

| 17 | Iowa | 7 | 7 | 1965 | 1987 |  |

| 18 | Kansas | 5 | 5 | 1968 | 1980 |  |

| 19 | Kentucky | 7 | 6 [note 4] | 1966 | 2009 |  |

| 20 | Louisiana | 0 | ||||

| 21 | Maine | 14 | 14 | 1966 | 1984 |  |

| 22 | Maryland | 6 | 5 [note 5] | 1964 | 1980 |  |

| 23 | Massachusetts | 11 | 10[note 3] | October 1971 | November 1987 |  |

| 24 | Michigan | 12 | 12[4] | 1967 | 1984 |  |

| 25 | Minnesota | 8 | 7 [note 6] | 1965 | 1980 |  |

| 26 | Mississippi | 5 | 5 | 1965 | 1976 |  |

| 27 | Missouri | 16 | 16 | June 1971 | May 1986 |  |

| 28 | Montana | 10 | 10 | 1966 | 1980 | |

| 29 | Nebraska | 5 | 5 | 1964 | 2006 |  |

| 30 | Nevada | 6 | 6 | 1968 | 1973 |  |

| 31 | New Hampshire | 11 | 11 | 1971 | 1987 |  |

| 32 | New Jersey | 11 | 10[note 7] | October 1965 | June 1983 | .jpg.webp) |

| 33 | New Mexico | 12 | 12 | 1969 | 1982 |  |

| 34 | New York | 28 | 26[note 7][note 8] | March 1964 | July 2014 | _-_Fayetteville_NY.jpg.webp) |

| 35 | North Carolina | 13 | 13 | 1967 | 1983 |  |

| 36 | North Dakota | 4 | 4 | 1960 | 1975 | |

| 37 | Northern Mariana Islands | 0 | ||||

| 38 | Ohio | 23 | 23 | 1965 | 1980 |  |

| 39 | Oklahoma | 3 | 3 | December 1974 | June 1983 | |

| 40 | Oregon | 11 | 11 | 1966 | June 2016 |  |

| 41 | Pennsylvania | 27 | 27 | March 1964 | January 2009 |  |

| 42 | Puerto Rico | 5 | 5 | 1975 | 1980 |  |

| 43 | Rhode Island | 1 | 1 | May 1974 | May 1974 |  |

| 44 | South Carolina | 6 | 6 | May 1974 | May 1986 |  |

| 45 | South Dakota | 13 | 12 [note 6] | 1965 | 1980 |  |

| 46 | Tennessee | 13 | 13 | 1966 | 1974 |  |

| 47 | Texas | 20 | 20 | 1965 | 2009 |  |

| 48 | Utah | 4 | 4 | October 1965 | 1977 |  |

| 49 | Vermont | 12 | 11[note 8] | 1967 | 2009 |  |

| 50 | Virgin Islands | 7 | 7 | 1980 | 1980 |  |

| 51 | Virginia | 10 | 10 | 1965 | 1987 | _(4578425529).jpg.webp) |

| 52 | Washington | 18 | 18 | 1965 | 2011 |  |

| 53 | Washington D.C. | 0 | ||||

| 54 | West Virginia | 16 | 15 [note 5] | 1964 | 2021 | |

| 55 | Wisconsin | 18 | 18 | 1964 | May 2012 |  |

| 56 | Wyoming | 6 | 5 [note 2] | October 1965 | December 1984 |  |

See also

Notes

- This step was dropped after 1979 but was reinstituted in 1999.

- Sand Creek shared between Colorado and Wyoming

- Bartholomew's Cobble shared between Connecticut and Massachusetts

- Ohio Coral Reef shared between Indiana and Kentucky

- Cranesville Swamp Nature Sanctuary shared between Maryland and West Virginia

- Ancient River Warren Channel shared between Minnesota and South Dakota

- Palisades of the Hudson shared between New Jersey and New York

- Chazy Fossil Reef shared between Vermont and New York

References

- "National Natural Landmarks Program". National Park Service. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- "High Plateaus, Smelly Caverns, and Coastal Dunes, Meet the Nation's Newest Natural Landmarks". National Park Service. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- "National Natural Landmarks Program; Final Rule 36 CFR 62," Federal Register Vol. 64, No. 91, Wednesday, May 12, 1999, pp. 25708-25723.

- Roscommon Red Pines, Department of Natural Resources.