Battle of Dun Nechtain

The Battle of Dun Nechtain or Battle of Nechtansmere (Old Welsh: Gueith Linn Garan) was fought between the Picts, led by King Bridei Mac Bili, and the Northumbrians, led by King Ecgfrith, on 20 May 685.

| Battle of Dun Nechtain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pictish-Northumbrian conflicts | |||||||

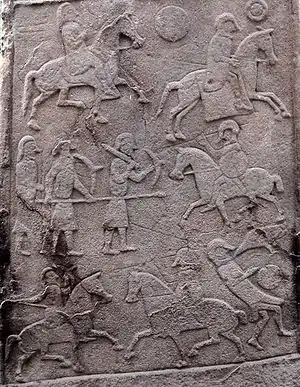

Pictish symbol stone depicting what was once generally accepted to be the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Pictland | Northumbria | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Bridei III | Ecgfrith † | ||||||

The Northumbrian hegemony over northern Britain, won by Ecgfrith's predecessors, had begun to disintegrate. Several of Northumbria's subject nations had rebelled in recent years, leading to a number of large-scale battles against the Picts, Mercians and Irish, with varied success. After sieges of neighbouring territories carried out by the Picts, Ecgfrith led his forces against them, despite advice to the contrary, in an effort to reassert his suzerainty over the Pictish nations.

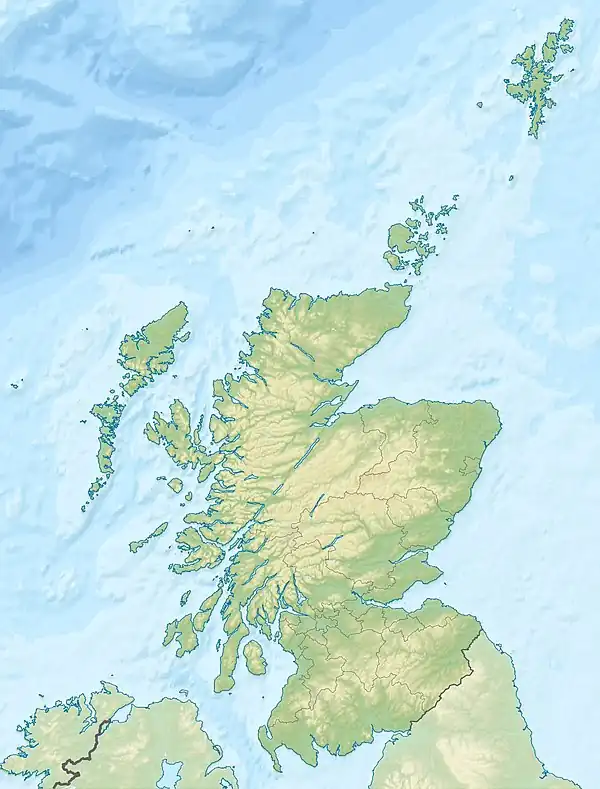

A feigned retreat by the Picts drew the Northumbrians into an ambush at Dun Nechtain near the lake of Linn Garan. The battle site has long been thought to have been near the present-day village of Dunnichen in Angus. Recent research, however, has suggested a more northerly location near Dunachton, on the shores of Loch Insh in Badenoch and Strathspey.

The battle ended with a decisive Pictish victory which severely weakened Northumbria's power in northern Britain. Ecgfrith was killed in battle, along with the greater part of his army. The Pictish victory marked their independence from Northumbria, who never regained their dominance in the north.

Background

During the seventh century AD, the Northumbrians gradually extended their territory to the north. The Annals of Tigernach record a siege of "Etain" in 638,[1] which has been interpreted as Northumbria's conquest of Eidyn (Edinburgh) during the reign of Oswald, marking the annexation of Gododdin territories to the south of the River Forth.[2]

To the north of the Forth, the Pictish nations consisted at this time of the Kingdom of Fortriu to the north of the Mounth, and a "Southern Pictish Zone" between there and the Forth.[3] Evidence from the eighth century Anglo-Saxon historian Bede points to the Picts also being subjugated by the Northumbrians during Oswald's reign,[4] and suggests that this subjugation continued into the reign of his successor, Oswiu.[5]

Ecgfrith succeeded Oswiu as king of Northumbria in 670. Soon after, the Picts rose in rebellion against Northumbrian subjugation at the Battle of Two Rivers, recorded in the 8th century by Stephen of Ripon, hagiographer of Wilfrid.[6] Ecgfrith was aided by a sub-king, Beornhæth, who may have been a leader of the Southern Picts,[7] and the rebellion ended in disaster for the Northern Picts of Fortriu. Their king, Drest mac Donuel, was deposed and was replaced by Bridei mac Bili.[8]

By 679, the Northumbrian hegemony seems to have started to fall apart. The Irish annals record a Mercian victory over Ecgfrith at which Ecgfrith's brother, Ælfwine of Deira, was killed.[9] Sieges were recorded at Dunnottar, in the northernmost region of the "Southern Pictish Zone" near Stonehaven in 680, and at Dundurn in Strathearn in 682.[10] The antagonists in these sieges are not recorded, but the most reasonable interpretation is thought to be that Bridei's forces were the assailants.[11]

Bridei is also recorded as having "destroyed" the Orkney Islands in 681,[12] at a time when the Northumbrian church was undergoing major religious reform. It had followed the traditions of the Columban church of Iona until the Synod of Whitby in 664 at which it pledged loyalty to the Roman Church. The Northumbrian diocese was divided and a number of new episcopal sees created. One of these was founded at Abercorn on the south coast of the Firth of Forth, and Trumwine was consecrated as Bishop of the Picts. Bridei, who was enthusiastically involved with the church of Iona,[13] is unlikely to have viewed an encroachment of the Northumbrian-sponsored Roman Church favourably.[14]

The attacks on the Southern Pictish Zone at Dunnottar and Dundurn represented a major threat to Ecgfrith's suzerainty.[15] Ecgfrith was contending with other challenges to his overlordship. In June 684, countering a Gaelic-Briton alliance, he sent his armies, led by Berhtred, son of Beornhæth, to Brega in Ireland. Ecgfrith's force decimated the local population and destroyed many churches, actions which are treated with scorn by Bede.[16]

Account of the battle

| "[T]he very next year [685AD], that same king [Egfrid], rashly leading his army to ravage the province of the Picts, much against the advice of his friends, and particularly of Cuthbert, of blessed memory, who had been lately ordained his bishop, the enemy made show as if they fled, and the king was drawn into the straits of inaccessible mountains, and slain with the greatest part of his forces, on the 20th of May, in the fortieth year of his age, and the fifteenth of his reign." |

| – Bede's account of battle from his Ecclesiastical History of England.[17] |

While none of the historical sources explicitly state Ecgfrith's reason for attacking Fortriu in 685, the consensus is that it was to reassert Northumbria's control over the Picts.[18] The most thorough description of the battle is given by Bede in his 8th-century work Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (The Ecclesiastical History of the English People), but this is still brief. Additional detail is given in the Irish annals of Ulster and Tigernach, and by the early Welsh historian Nennius in his Historia Brittonum (written around a century later).[19]

Ecgfrith's attack on Fortriu was made against the counsel of his advisors, including Cuthbert, who had recently been made Bishop of Lindisfarne. The Picts, led by Bridei, feigned retreat and drew Ecgfrith's Northumbrian force into an ambush on Saturday, 20 May 685 at a lake in mountains near Duin Nechtain. The Northumbrian army was defeated and Ecgfrith slain.[19]

Location

| "Egfrid is he who made war against his cousin Brudei, king of the Picts, and he fell therein with all the strength of his army and the Picts with their king gained the victory; and the Saxons never again reduced the Picts so as to exact tribute from them. Since the time of this war it is called Gueith Lin Garan." |

| – Nennius' account of battle from Historia Brittonum.[20] |

The site of the battle is uncertain. Until relatively recently the battle was most commonly known by its Northumbrian name, the Battle of Nechtansmere, from the Old English for 'Nechtan's lake', following 12th-century English historian Symeon of Durham.[21] The location of the battle near a lake is reinforced by Nennius' record of the conflict as Gueith Linn Garan, Old Welsh for 'Battle of Crane Lake'. It is likely that Linn Garan was the original Pictish name for the lake.[22]

The most complete narrative of the battle itself is given by Bede, who nevertheless fails to inform us of the location other than his mention that it took place 'in straits of inaccessible mountains'.[17]

The Irish Annals have provided perhaps the most useful resource for identifying the battle site, giving the location as Dún Nechtain, 'Nechtan's Fort', a name that has survived into modern usage in two separate instances.[23]

Dunnichen

| "The battle of Dún Nechtain was fought on Saturday, May 20th, and Egfrid son of Oswy, king of the Saxons, who had completed the 15th year of his reign, was slain therein with a great body of his soldiers. ... |

| – Account of battle from the Annals of Ulster.[24] |

| "The battle of Dún Nechtain was carried out on the twentieth day of the month of May, a Sunday, in which Ecfrith son of Osu, king of the Saxons, in the 15th year of his rule completed, with magna caterua of his soldiers was killed by Bruide son of Bile king of Fortriu." |

| – Account of battle from the Annals of Tigernach.[25] |

Dunnichen in Angus was first identified as a possible location for the battle by antiquarian George Chalmers in the early 19th century.[26] Chalmers notes that the name 'Dunnichen' can be found in early charters of Arbroath Abbey as 'Dun Nechtan'.[27] He further suggests a site, 'Dunnichen Moss' (grid reference NO516489), to the east of the village, which he informs us had recently been drained but can be seen in old maps as a small lake.[28] Earlier local tradition, related by Headrick in the Second Statistical Account, claimed that the site was the location of the Battle of Camlann, where King Arthur fought Mordred.[29]

More recent suggestions for the battle site include the valley to the north of Dunnichen Hill, centering on Rescobie Loch (grid reference NO512518) and Restenneth Loch (grid reference NO483518), which is now much reduced following drainage in the 18th century.[30]

The battle scene inscribed on the Aberlemno kirk yard stone is often cited as evidence for the battle site. This interpretation was made based on the stone's proximity to Dunnichen, only 3 miles (5 km) to the north, but while the short distance seems compelling, the stone is unlikely to be any earlier than mid-8th century,[31] and the ornamentation of the stone, including the animal forms used and the style of weaponry depicted, suggests it may be as late as the mid-9th century.[32] Prior to being linked with the Battle of Nechtansmere, the Aberlemno stone had been cited as evidence for the Battle of Barry (now known to be historically inauthentic),[33] and there are a number of other possible interpretations for the carving.[34]

Dunachton

In a paper published in 2006, historian Alex Woolf gives a number of reasons for doubting Dunnichen as the battle site, most notably the absence of "inaccessible mountains" in mid-Angus. He makes a case for an alternative site at Dunachton in Badenoch (grid reference NH820047), on the north-western shore of Loch Insh, which shares Dunnichen's toponymical origin of Dún Nechtain.[21] James Fraser of Edinburgh University suggests that, while it is too early to discount Dunnichen as a potential battle site, locating it there requires an amount of "special pleading" that Dunachton does not need.[35]

Aftermath

Ecgfrith's defeat at Dun Nechtain devastated Northumbria's power and influence in the North of Britain. Bede recounts that the Picts recovered their lands that had been held by the Northumbrians and Dál Riatan Scots. He goes on to tell how the Northumbrians who did not flee the Pictish territory were killed or enslaved.[17]

The Northumbrian/Roman diocese of the Picts was abandoned, with Trumwine and his monks fleeing to Whitby, stalling Roman Catholic expansion in Scotland.[17]

While further battles between the Northumbrians and Picts are recorded, for example in 697 when Beornhæth's son Berhtred was killed,[36] the Battle of Dunnichen marks the point in which Pictish independence from Northumbria was permanently secured.[37]

Notes

- Annals of Tigernach T640.1; Woolf (2001)

- Jackson 1959; Woolf 2001

- Woolf 2006, Fraser 2009, p. 184

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, III: VI (Oswald "brought under his dominion all the nations and provinces of Britain, which are divided into four languages, viz. the Britons, the Picts, the Scots, and the English.")

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, III: XXIV Oswiu "subdued the greater part of the Picts to the dominion of the English" in 658.

- Alcock 2003, p. 131; Colgrave 1927, pp. 41–43

- Fraser 2009, p. 201

- Fraser 2009, pp. 201–202

- Annals of Ulster U680.4

- Annals of Ulster U681.5; Fraser (2009) p. 214 Annals of Ulster U.683.3

- Fraser 2009, p. 207

- Annals of Ulster 682.4; Annals of Tigernach 682.5

- Fraser 2009, p. 237

- Veitch 1997

- Fraser 2009, p. 215

- Annals of Ulster U685.2; Annals of Tigernach T685.2; Bede, Ecclesiastical History IV: XXIV; Annals of Clonmacnoise p. 109

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History IV: XXVI

- Alcock 2003, p. 133; Fraser 2009, p. 215

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History IV:XXVI; Annals of Ulster U686.1; Annals of Tigernach T686.4; Nennius, Historia Brittonum 57

- Nennius, Historia Brittonum, 57.

- Woolf (2006)

- This was originally suggested by Jackson (1963, p. 40). Although alternative suggestions have been made, the orthodox view is that Jackson was correct in his assessment of Pictish as a Brythonic language (Forsyth, 1997)

- Annals of Ulster U686.1; Annals of Tigernach T686.4; Woolf (2006)

- Annals of Ulster U686.1

- Annals of Tigernach T686.4

- Woolf (2006); Chalmers (1887)

- And spelling variations. See for example: Innes and Chalmers (1843)

- Chalmers (1887). The example Chalmers gives is Ainslie's map of Forfarshire (1794), which does not show a lake in that position, nor do earlier maps, for example Pont (c. 1583–1596); Roy (1747–1755)

- Headrick also mentions Lothius as a protagonist.

Headrick, James (1845). "Parish of Dunnichen". New Statistical Account of Scotland. Retrieved 27 July 2010. - Woolf (2006); Fraser (2006) pp. 68–70

- Cummins (1999) pp. 98–103

- Laing (2000)

- Mitchel (1792); Crombie (1842); Jervise (1856) Jervise, writing in 1856, recounts Chalmers' identification of Dunnichen as the battle site while mentioning, in the same article, the Aberlemno stone solely in relation to the Battle of Barry.

- For example, W.A. Cummins suggests the possibility that the stone is a memorial to 9th century Pictish king Óengus mac Fergusa. Cummins (1999) pp. 98–103

- Fraser (2009) pp. 215–216

- Annals of Ulster 698.2

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History IV: XXVI; Colgrave p. 43; Cummins (2009) p. 107; Fraser (2009) p. 216

References

- The Annals of Ulster. CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- The Annals of Tigernach. CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- Murphy, D, ed. (1893–95). The Annals of Clonmacnoise. Dublin: Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- Ainslie, J (1794). "Map of the county of Forfar or Shire of Angus". National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- Alcock, Leslie (2003). Kings & Warriors, Craftsmen & Priests in Northern Britain AD 550–850 (PDF). Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

- Bede. "Ecclesiastical History of England III". Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- Bede. "Ecclesiastical History of England IV". Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- Chalmers, George (1887). Caledonia: or a historical and topographical account of North Britain, from the most ancient to the present times with a dictionary of places chorographical and philological. Vol. 1 (new ed.). Paisley: Alex. Gardner.

- Colgrave, Bertram (1927). The Life of Bishop Wilfrid by Eddius Stephanus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521313872.

- Crombie, J. (1842). The new statistical account of Scotland, Parish of Aberlemno, Forfarshire. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- Cummins, WA (1999). The Picts and their symbols. Stroud, Gloucester: Sutton Publishing.

- Cummins, WA (2009). The Age of the Picts (2nd ed.). Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucester: The History Press.

- Forsyth, K. (1997). Language in Pictland, the case against 'non-Indo-European Pictish' (PDF). Munster: Nodus Publikationen. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- Fraser, James E. (2006). The Pictish Conquest: The Battle of Dunnichen 685 and the Birth of Scotland. Stroud, Gloucester: Tempus.

- Fraser, James E (2009). From Caledonia to Pictland: Scotland to 795. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748612321.

- Innes, C.; Chalmers, P., eds. (1843). Liber S. Thome de Aberbrothoc; Registrorum Abbacie de Aberbrothoc. 1178–1329. Edinburgh: The Bannatyne Club.

- Jackson, Kenneth (1959). "Edinburgh and the Anglian occupation of Lothian". In Clemoes, Peter (ed.). The Anglo-Saxons: some aspects of their history and culture presented to Bruce Dickins. London: Bowes and Bowes. pp. 35–42.

- Jackson, Kenneth (1963). "On the Northern British Section in Nennius". In Chadwick, Nora (ed.). Celt and Saxon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jervise, Andrew (1856). "Notices descriptive of the localities of certain sculptured stone monuments in Forfarshire, &c. (Part I.)" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 2: 187–201. doi:10.9750/PSAS.002.187.201. S2CID 245401875. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2007.

- Laing, L (2000). "The Chronology and Context of Pictish Relief Sculpture" (PDF). Medieval Archaeology. 34: 81–114. doi:10.1179/med.2000.44.1.81. S2CID 162209011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2011.

- Mitchel, A. (1792). The statistical account of Scotland, Parish of Aberlemno, County of Forfar. ISBN 978-0748610716. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- Nennius. "Historia Brittonum". Archived from the original on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- Pont, T. "Lower Angus and Perthshire east of the Tay". c. 1583–1596. National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- Roy, W (1747–55). "Military Survey of Scotland". National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 18 August 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- Veitch, K (1997). "The Columban Church in northern Britain, 664–717: a reassessment" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 127: 627–647. doi:10.9750/PSAS.127.627.647. S2CID 59506331. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- Woolf, Alex (2001), Lynch, Michael (ed.), "Britons and Angles", The Oxford Companion to Scottish History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 45–47, ISBN 0192116967

- Woolf, Alex (2006). "Dun Nechtain, Fortriu and the Geography of the Picts". The Scottish Historical Review. 85 (2): 182–201. doi:10.1353/shr.2007.0029. S2CID 201796703.