Needlestick injury

A needlestick injury is the penetration of the skin by a hypodermic needle or other sharp object that has been in contact with blood, tissue or other body fluids before the exposure.[1] Even though the acute physiological effects of a needlestick injury are generally negligible, these injuries can lead to transmission of blood-borne diseases, placing those exposed at increased risk of infection from disease-causing pathogens, such as the hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Among healthcare workers and laboratory personnel worldwide, more than 25 blood-borne virus infections have been reported to have been caused by needlestick injuries.[2] In addition to needlestick injuries, transmission of these viruses can also occur as a result of contamination of the mucous membranes, such as those of the eyes, with blood or body fluids, but needlestick injuries make up more than 80% of all percutaneous exposure incidents in the United States.[1][3] Various other occupations are also at increased risk of needlestick injury, including law enforcement, laborers, tattoo artists, food preparers, and agricultural workers.[3][4]

| Needlestick injury | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Percutaneous injury, percutaneous exposure incident, sharps injury |

| |

| A sharps container is a recommended method for collecting needles while reducing the risk of needlestick injuries | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine, Infectious disease |

Increasing recognition of the unique occupational hazard posed by needlestick injuries, as well as the development of efficacious interventions to minimize the largely preventable occupational risk, encouraged legislative regulation in the US, causing a decline in needlestick injuries among healthcare workers.[5][6]

Health effects

While needlestick injuries have the potential to transmit bacteria, protozoa, viruses and prions,[6] the risk of contracting hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV is the highest.[7] The World Health Organization estimated that in 2000, 66,000 hepatitis B, 16,000 hepatitis C, and 1,000 HIV infections were caused by needlestick injuries.[4][2][7] In places with higher rates of blood-borne diseases in the general population, healthcare workers are more susceptible to contracting these diseases from a needlestick injury.[7]

Hepatitis B carries the greatest risk of transmission, with 10% of exposed workers eventually showing seroconversion and 10% having symptoms.[8] Higher rates of hepatitis B vaccination among the general public and healthcare workers have reduced the risk of transmission;[2] non-healthcare workers still have a lower HBV vaccination rate and therefore a higher risk.[9] The transmission rate of hepatitis C has been reported at 1.8%,[10] but newer, larger surveys have shown only a 0.5% transmission rate.[11] The overall risk of HIV infection after percutaneous exposure to HIV-infected material in the health care setting is 0.3%.[2] Individualized risk of blood-borne infection from a used biomedical sharp is further dependent upon additional factors. Injuries with a hollow-bore needle, deep penetration, visible blood on the needle, a needle located in a deep artery or vein, or a biomedical device contaminated with blood from a terminally ill patient increase the risk for contracting a blood-borne infection.[12][9]

Psychological effects

The psychological effects of occupational needlestick injuries can include health anxiety, anxiety about disclosure or transmission to a sexual partner, trauma-related emotions, and depression. These effects can cause self-destructive behavior or functional impairment in relationships and daily life. This is not mitigated by knowledge about disease transmission or post-exposure prophylaxis. Though some affected people have worsened anxiety during repeated testing, anxiety and other psychological effects typically abate after testing is complete. A minority of people affected by needlestick injuries may have lasting psychological effects, including post-traumatic stress disorder.[13]

In cases where an injury was sustained with a clean needle (i.e. exposure to body fluids had not occurred), the likelihood of infection is generally minimal. Nonetheless, workers are often obligated to report the incident as per the facility's protocol regarding occupational safety.

Cause

Needlestick injuries occur in the healthcare environment. When drawing blood, administering an intramuscular or intravenous drug, or performing any procedure involving sharps, accidents can occur and facilitate the transmission of blood-borne diseases. Injuries also commonly occur during needle recapping or via improper disposal of devices into an overfilled or poorly located sharps container. Lack of access to appropriate personal protective equipment, or alternatively, employee failure to use provided equipment, increases the risk of occupational needlestick injuries.[2] Needlestick injuries may also occur when needles are exchanged between personnel, loaded into a needle driver, or when sutures are tied off while still connected to the needle. Needlestick injuries are more common during night shifts[14] and for less experienced people; fatigue, high workload, shift work, high pressure, or high perception of risk can all increase the chances of a needlestick injury. During surgery, a surgical needle or other sharp instrument may inadvertently penetrate the glove and skin of operating room personnel;[7] scalpel injuries tend to be larger than a needlestick. Generally, needlestick injuries cause only minor visible trauma or bleeding; however, even in the absence of bleeding the risk of viral infection remains.

Prevention

The prevention of needlestick injuries should focus on those health care workers that are most at risk.

The group most at risk are surgeons and surgical staff in the operating room who sustain injuries from suture needles and other sharps used in operations. There are basically three complementary approaches to prevention of these sharps injuries. The first one is the use of tools that have been changed so that they are less likely to lead to a sharps injury such as blunt or taper-point surgery needles and safety engineered scalpels.[7] Needleless connectors (NCs) were introduced in the 1990s to reduce the risk of health care worker needlestick injuries.[15] The second is to start using safe working practices such as the hands-free technique.[16] The third line of prevention is increased personal protective equipment such as the use of two pairs of gloves.[17] In addition to these preventive approaches implementation measures are necessary because the measures are not universally taken up. To achieve better implementation, legislation, education and training are necessary among all health care workers at risk.[18]

Another large group at risk are nurses but their frequency of exposure is much less than in surgeons. Their main risk comes from the use and disposal of injection syringes. The same prevention approaches can be implemented here. There are many so-called safety engineered devices such as retractable needles, needle shields/sheaths, needle-less IV kits, and blunt or valved ends on IV connectors.[19] The use of extra gloves is less common among nurses.

Some studies have found that safer needles attached to syringes reduce injuries, but others have shown mixed results or no benefit.[2] The adherence to "no-touch" protocols that eliminate direct contact with needles during use and disposal greatly reduces the risk of needlestick injuries. In the surgical setting, especially in abdominal operations, blunt-tip suture needles were found to reduce needle stick injuries by 69%. Blunt-tip or tapered-tip suture needles can be used to sew muscle and fascia. Though they are more expensive than sharp-tipped needles, this cost is balanced by the reduction in injuries, which are expensive to treat.[7][20][21] Sharp-tipped needles cause 51–77% of surgical needlestick injuries.[22] The American College of Surgeons (ACS) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have endorsed the adoption of blunt-tip suture needles for suturing fascia and muscle.[20][23][24] Hollow-bore needles pose a greater risk of injury than solid needles, but hollow-bore needle injuries are highly preventable: 25% of hollow-bore needle injuries to healthcare professionals can be prevented by using safer needles .[2] Gloves can also provide better protection against injuries from tapered-tip as opposed to sharp-tipped needles.[7] In addition, a Cochrane review showed that the use of two pairs of gloves (double gloving) can significantly reduce the risk of needle stick injury in surgical staff.[17] Triple gloving may be more effective than double gloving, but using thicker gloves does not make a difference.[17] A Cochrane review found low quality evidence showing that safety devices on IV start kits and venipuncture equipment reduce the frequency of needlestick injuries.[19] However, these safety systems can increase the risk of exposure to splashed blood.[2] Education with training for at-risk healthcare workers can reduce their risk of needlestick injuries.[25][21] The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has a campaign (Stop Sticks) to educate at-risk healthcare workers.[26]

Treatment

After a needlestick injury, certain procedures can minimize the risk of infection. Lab tests of the recipient should be obtained for baseline studies, including HIV, acute hepatitis panel (HAV IgM, HBsAg, HB core IgM, HCV) and for immunized individuals, HB surface antibody. Unless already known, the infectious status of the source needs to be determined.[27] Unless the source is known to be negative for HBV, HCV, and HIV, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) should be initiated, ideally within one hour of the injury.[28]

Hepatitis B

The risk of hepatitis B (e antigen positive) seroconversion is estimated at 37–62%, significantly more than other blood borne pathogens.[7] After exposure to the hepatitis B virus (HBV), appropriate and timely prophylaxis can prevent infection and subsequent development of chronic infection or liver disease. The mainstay of PEP is the hepatitis B vaccine; in certain circumstances, hepatitis B immunoglobulin is recommended for added protection.[29][30]

Hepatitis C

The risk of hepatitis C seroconversion is estimated at 0.3–0.74%.[14] Immunoglobulin and antivirals are not recommended for hepatitis C PEP.[27] There is no vaccine for the hepatitis C virus (HCV); therefore, post-exposure treatment consists of monitoring for seroconversion.[29] There is limited evidence for the use of antivirals in acute hepatitis C infection.

HIV

The risk of HIV transmission with a skin puncture is estimated at 0.3%.[6] If the status of the source patient is unknown, their blood should be tested for HIV as soon as possible following exposure. The injured person can start antiretroviral drugs for PEP as soon as possible, preferably within three days of exposure.[28] There is no vaccine for HIV.[29] When the source of blood is known to be HIV positive, a 3-drug regimen is recommended by the CDC; those exposed to blood with a low viral load or otherwise low risk can use a 2-drug protocol.[12] The antivirals are taken for 4 weeks and can include nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NtRTIs), Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), protease inhibitors (PIs), or fusion inhibitors. All of these drugs can have severe side effects. PEP may be discontinued if the source of blood tests HIV-negative. Follow-up of all exposed individuals includes counseling and HIV testing for at least six months after exposure. Such tests are done at baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months and longer in specific circumstances, such as co-infection with HCV.[28]

Epidemiology

In 2007, the World Health Organization estimated annual global needlestick injuries at 2 million per year, and another investigation estimated 3.5 million injuries yearly.[4][7][19] The European Biosafety Network estimated 1 million needlestick injuries annually in Europe.[29] The US Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) estimates 5.6 million workers in the healthcare industry are at risk of occupational exposure to blood-borne diseases via percutaneous injury.[20] The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates more than 600,000 needlestick injuries occur among healthcare workers in the US annually.

It is difficult to establish correct figures for the risk of exposure or the incidence of needlestick injuries. First of all it is difficult to observe a needlestick injury, either in oneself or in other persons. Glove perforations in surgeons are considered a reasonable proxy that can be measured objectively. Even though glove perforations can be objectively measured, it is still unclear what the relation is between glove perforations and needlestick injuries.[17] Another problem is underreporting of needlestick injuries. It is estimated that half of all occupational needlestick injuries are not reported.[14][22] Additionally, an unknown number of occupational needlestick injuries are reported by the affected employee, yet due to organizational failure, institutional record of the injury does not exist.[22] This makes it difficult to determine what the exact risk of exposure is for various medical occupations. Most studies use databases of reported needlestick injuries to determine preventable causes.[1] However this is different from establishing an exposure risk.

Among healthcare workers, nurses and physicians appear especially at risk; those who work in an operating room environment are at the highest risk.[7][31] An investigation among American surgeons indicates that almost every surgeon experienced at least one such injury during their training.[32] More than half of needlestick injuries that occur during surgery happen while surgeons are sewing the muscle or fascia.[20] Within the medical field, specialties differ in regard to the risk of needlestick injury: surgery, anesthesia, otorhinolaryngology (ENT), internal medicine, and dermatology have high risk, whereas radiology and pediatrics have relatively low rates of injury.[28][33] A systematic review of 45 studies of sharps injuries in surgical staff found that sharps injuries occur once in 10 operations per staff member.[34] Per 100 person-years, the injury rate in surgical staff was 88.2 (95% CI, 61.3-126.9; 21 studies) for self-reported injuries, 40.0 for perforations (95% CI, 19.2-83.5; 15 studies), and 5.8 for administrative injuries (95% CI, 2.7-12.2; 5 studies). Self-report probably overestimates the real risk and administrative data underestimate the risk considerably. Perforation data are probably the most valid indicators. Considering that the perforation rates provided here are much lower than the self-reported injuries used to calculate the burden of disease due to sharps injuries by the WHO, these calculations should be revised.[35]

In the United States, approximately half of all needlestick injuries affecting health care workers are not reported, citing the long reporting process and its interference with work as their reason for not reporting an incident. The availability of hotlines, witnesses, and response teams can increase the percentage of reports.[10] Physicians are particularly likely to leave a needlestick unreported, citing worries about loss of respect or a low risk perception. Low risk perception can be caused by poor knowledge about risk, or an incorrect estimate of a particular patient's risk.[6][10][11][36] Surveillance systems to track needlestick injuries include the National Surveillance System for Healthcare Workers (NaSH), a voluntary system in the northeastern United States, and the Exposure Prevention Information Network (EPINet), a recording and tracking system that also gathers data.[1][12]

Society and culture

Cost

There are indirect and direct costs associated with needlestick injuries. The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) determined that requiring hospitals to use safety-engineered needles would result in substantial savings due to the reduction in needlestick injuries requiring treatment. Costs of needlestick injuries include prophylaxis, wages and time lost by workers, quality of life, emotional distress, costs associated with drug toxicity, organizational liability, mortality, quality of patient care, and workforce reduction.[7][8] Testing and follow-up treatment for healthcare workers who experienced a needlestick injury was estimated at $5,000 in the year 2000, depending upon the medical treatment provided. The American Hospital Association found that a case of infection by blood-borne pathogens could cost $1 million for testing, follow-up, and disability payments. An estimated $1 billion annually is saved by preventing needlestick injuries among healthcare workers in the US, including fees associated with testing, laboratory work, counseling, and follow-up costs.[37]

Legislation

In the United States, the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act of 2000 and the subsequent Bloodborne Pathogens Standard of 2001 require safer needle devices, employee input, and records of all sharps injuries in healthcare settings.[6][20][38][39] In the US, nonsurgical needlestick injuries decreased by 31.6% in the five years following the passage of the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act. However, this legislation did not affect surgical settings, where injuries increased 6.5% in the same period.[3][7][26]

Outside healthcare

The Coalition for Safe Community Needle Disposal estimates there are over 7.5 billion syringes used for home medical care in the United States.[41] This large amount of home medical syringes has added to the problem of non-healthcare related needlestick injuries due to mishandling and improper disposal of the syringes. Blood on any sharp instrument may be infectious, whether or not the blood is fresh. HIV and the hepatitis C virus (HCV) are only viable for hours after blood has dried, but the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is stable even when dried.[30] The risk of hepatitis B transmission in the community is also increased due to the higher prevalence of hepatitis B in the population than HIV and the high concentration of HBV in the blood.[42]

Many professions are at risk of needlestick injury including law enforcement, waste collectors, laborers, and agricultural workers. There is no standard system for collecting and tracking needlestick injuries in the community, which makes it difficult to measure the full impact of this problem.[41] Law enforcement workers, like healthcare workers, under-report needlestick injuries. In San Diego, 30% of police reported needle sticks. A study of 1,333 police officers in the Denver Police Department found that only 43.4% reported a needlestick injury they received; 42% of which occurred during their evening shift. Most of the needlestick injuries experienced by these workers occurred in their first 5 years of employment.[43] In New York City, a study found a rate of 38.7 exposures (needlesticks and human bites) per 10,000 police officers.[44] In Tijuana, Mexico, 15.3% of police officers reported ever having a needlestick injury, with 14.3% reporting a needlestick within the past year.[45]

Needlestick injuries are among the top three injuries that occur among material-recovery facility workers who sort through trash to remove recyclable items from the community-collected garbage.[41] Housekeeping and janitorial workers in public sites, including hotels, airports, indoor and outdoor recreational venues, theaters, retails stores, and schools are at daily risk of exposure to contaminated syringes.[41] A small study of sanitation workers in Mexico City found that 34% reported needlestick injuries while working in the past year.[46]

Needlestick injuries that occur in children from discarded needles in community settings, such as parks and playgrounds, are especially concerning. While the exact number of needlestick injuries in children in the US is unknown, even one injury in a child is enough to cause public alarm. Studies in Canada have reported 274 injuries from needlesticks in children with the majority being boys (64.2%) and occurring from needles discarded in streets and/or parks (53.3%).[47]

There are a number of ways in which needlestick injuries could be prevented. First and foremost, increased education in the community is vital. It is especially important to educate kids while they are young. Studies of injuries from discarded needles have reported that the average age of children injured is between five and eight years.[48] In one study, 15% of injuries occurred in children pretending to use drugs.[48] Therefore, children should be taught at a young age about the risks of handling needles and the correct actions to take if they find a syringe.

More outreach programs for addiction treatment and infection prevention programs for injection drug users would be very beneficial. Public needle disposal and syringe service programs (SSPs) or needle exchange programs (NEPs) have also proven to reduce the number of needles discarded in public areas. According to the CDC, these programs are effective in the prevention of HIV, and they help reduce the risk of infection with HCV.[49] Additionally, in 2004, the Environmental Protection Agency came up with a number of program options for safe disposal including:

- Drop-off collection sites

- Syringe exchange programs

- Mail-back programs

- Home needle destruction devices

- Household hazardous waste collection sites

- Residential waste special pick-up programs[41]

In the event that needlestick prevention programs are not put in place in a given community, a 1994 study suggests an alternative for "high risk" areas. The study proposed the implementation of a vaccination effort to give children a routine prophylaxis against hepatitis B to prevent the development of the illness in the event that a child encounters an improperly disposed needle.[50][41] [42] [47][51][52][49]

Needle exchange programs

Needle exchange programs were first established in 1981 in Amsterdam as a response from the injecting-drug community to an influx of hepatitis B.[31] Spurred to urgency by the introduction of HIV/AIDS, needle syringe programs quickly became an integral component of public health across the developed world.[32][33][43] These programs function by providing facilities in which people who use injecting drugs can receive sterile syringes and injection equipment.[31][43][44][53] Preventing the transmission of blood-borne disease requires sterile syringes and injection equipment for each unique injection,[44][53] which is necessarily predicated upon access and availability of these materials at no cost for those using them.[43][44]

Needle exchange programs are an effective way of decreasing the risk associated with needlestick injuries. These programs remove contaminated syringes from the street, reducing the risk of inadvertent transmission of blood-borne infections to the surrounding community and to law enforcement. A study in Hartford, Connecticut found that needlestick injury rates among Hartford police officers decreased after the introduction of a needle exchange program: six injuries in 1,007 drug-related arrests for the 6-month period before vs. two in 1,032 arrests for the 6-month period after.[39]

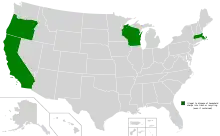

Data almost universally confirm the value of needle exchange programs, which substantially decrease the risk of HIV among injectable drug users and do not carry unintended negative consequences.[31][32][33][44][54] US states that publicly fund exchange programs are associated with reduced rates of HIV transmission, increased availability of sterile syringes among injecting drug users, and increased provision of health and social services to users. States that do not fund needle exchange programs are associated with increased rates of HIV/AIDS.[55]

Nevertheless, the US government has explicitly prohibited federal funding for needle exchange programs since 1988, as part of the zero tolerance drug policy in that country.[31][32][55] Needle exchange programs have therefore been sparsely implemented in the United States.[33][55]

References

- "The National Surveillance System for Healthcare Workers (NaSH) Summary Report for Blood and Body Fluid Exposure (1995–2007)" (PDF). CDC. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Tarigan, Lukman H.; Cifuentes, Manuel; Quinn, Margaret; Kriebel, David (1 July 2015). "Prevention of needle-stick injuries in healthcare facilities: a meta-analysis". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 36 (7): 823–29. doi:10.1017/ice.2015.50. ISSN 1559-6834. PMID 25765502. S2CID 20953913.

- Leigh, JP; Markis, CA; Iosif, A; Romano, PS (2015). "California's nurse-to-patient ratio law and occupational injury". International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 88 (4): 477–84. doi:10.1007/s00420-014-0977-y. PMC 6597253. PMID 25216822.

- Alamgir, H; Yu, S (2008). "Epidemiology of occupational injury among cleaners in the healthcare sector". Occupational Medicine. 58 (6): 393–99. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqn028. PMID 18356143.

- Wicker, S; Ludwig, A; Gottschalk, R; Rabenau, HF (2008). "Needlestick injuries among health care workers: Occupational hazard or avoidable hazard?". Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 120 (15–16): 486–92. doi:10.1007/s00508-008-1011-8. PMC 7088025. PMID 18820853.

- Phillips, EK; Conaway, M; Parker, G; Perry, J; Jagger, J (2013). "Issues in Understanding the Impact of the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act on Hospital Sharps Injuries". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 34 (9): 935–39. doi:10.1086/671733. PMID 23917907. S2CID 25667952.

- Parantainen, Annika; Verbeek, Jos H.; Lavoie, Marie-Claude; Pahwa, Manisha (1 January 2011). "Blunt versus sharp suture needles for preventing percutaneous exposure incidents in surgical staff". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (11): CD009170. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009170.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7387125. PMID 22071864.

- Office, U. S. Government Accountability (17 November 2000). "Occupational safety: Selected cost and benefit implications of needlestick prevention devices for hospitals" (GAO-01-60R). United States General Accounting Office. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Rachiotis, G; Papagiannis, D; Markas, D; Thanasias, E; Dounias, G; Hadjichristodoulou, C (2012). "Hepatitis B virus infection and waste collection: Prevalence, risk factors, and infection pathway". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 55 (7): 650–55. doi:10.1002/ajim.22057. PMID 22544469.

- Makary, MA; Al-Attar, A; Holzmueller, CG; Sexton, JB; Syin, D; Gilson, MM; Sulkowski, MS; Pronovost, PJ (2007). "Needlestick Injuries among surgeons in training". The New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (26): 2693–99. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa070378. PMID 17596603.

- Elmiyeh, B; Whitaker, IS; James, MJ; Chahal, CA; Galea, A; Alshafi, K (July 2004). "Needle-stick injuries in the National Health Service: a culture of silence". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 97 (7): 326–27. doi:10.1177/014107680409700705. PMC 1079524. PMID 15229257.

- "Needlestick and Sharp-Object Injury Reports". EPINet Multihospital Sharps Injury Surveillance Network. International Healthcare Worker Safety Center. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- Wald, J (2009). "The psychological consequences of occupational blood and body fluid exposure injuries". Disability & Rehabilitation. 31 (23): 1963–69. doi:10.1080/09638280902874147. PMID 19479544. S2CID 29903130.

- Laramie, AK; Davis, LK; Miner, C; Pun, VC; Laing, J; DeMaria, A (March 2012). "Sharps injuries among hospital workers in Massachusetts, 2010: findings from the Massachusetts Sharps Injury Surveillance System" (PDF). Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Slater, Karen, Cooke, Marie, Fullerton, Fiona, et al. Peripheral intravenous catheter needleless connector decontamination study-Randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2020;48(9):1013–1018. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2019.11.030.

- Stringer, Bernadette; Haines, A. Ted; Goldsmith, Charles H.; Berguer, Ramon; Blythe, Jennifer (2009). "Is use of the hands-free technique during surgery, a safe work practice, associated with safety climate?". American Journal of Infection Control. 37 (9): 766–72. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2009.02.014. PMID 19647344.

- Mischke, Christina; Verbeek, Jos H.; Saarto, Annika; Lavoie, Marie-Claude; Pahwa, Manisha; Ijaz, Sharea (1 January 2014). "Gloves, extra gloves or special types of gloves for preventing percutaneous exposure injuries in healthcare personnel". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD009573. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009573.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 24610769.

- Hasak, Jessica M.; Novak, Christine B.; Patterson, Jennifer Megan M.; Mackinnon, Susan E. (1 February 2018). "Prevalence of Needlestick Injuries, Attitude Changes, and Prevention Practices Over 12 Years in an Urban Academic Hospital Surgery Department". Annals of Surgery. 267 (2): 291–96. doi:10.1097/sla.0000000000002178. ISSN 0003-4932. PMID 28221166. S2CID 10024783.

- Reddy, V (2017). "Devices for preventing percutaneous exposure injuries caused by needles in healthcare personnel". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 (11): CD009740. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009740.pub3. PMC 6491125. PMID 29190036.

- Kirchner, B (2012). "Safety in ambulatory surgery centers: Occupational Safety and Health Administration surveys". AORN Journal. 96 (5): 540–45. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2012.08.010. PMID 23107034.

- Yang, L; Mullan, B (2011). "Reducing needle stick injuries in healthcare occupations: an integrative review of the literature". ISRN Nursing. 2011: 1–11. doi:10.5402/2011/315432. PMC 3169876. PMID 22007320.

- Boden, LI; Petrofsky, YV; Hopcia, K; Wagner, GR; Hashimoto, D (2015). "Understanding the hospital sharps injury reporting pathway". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 58 (3): 282–89. doi:10.1002/ajim.22392. PMC 5077298. PMID 25308763.

- SoRelle, R (2000). "Precautions Advised to Prevent Needlestick Injuries Among US Healthcare Workers". Circulation. 101 (3): E38. doi:10.1161/01.cir.101.3.e38. PMID 10645936.

- "Blunt-Tip Surgical Suture Needles Reduce Needlestick Injuries and the Risk of Subsequent Bloodborne Pathogen Transmission to Surgical Personnel: FDA, NIOSH and OSHA Joint Safety Communication". Food and Drug Administration. 30 May 2012. Archived from the original on 22 July 2017.

- Tarigan, LH; Cifuentes, M; Quinn, M; Kriebel, D (2015). "Prevention of needle-stick injuries in healthcare facilities: a meta-analysis". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 36 (7): 823–29. doi:10.1017/ice.2015.50. PMID 25765502. S2CID 20953913.

- "Stop Sticks – NIOSH". cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- "Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease". MMWR. CDC. 47 (RR-19): 1–39. 1998. PMID 9790221.

- Kuhar, DT; Henderson, DK; Struble, KA; Heneine, W; Thomas, V; Cheever, LW; Gomaa, A; Panlilio, AL; US Public Health Service Working, Group (September 2013). "Updated US Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency virus and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 34 (9): 875–92. doi:10.1086/672271. PMID 23917901. S2CID 17032413. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- Lavoie, M; Verbeek, JH; Pahwa, M (2014). "Devices for preventing percutaneous exposure injuries caused by needles in healthcare personnel". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3. Art. No.: CD009740): CD009740. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009740.pub2. PMID 24610008.

- Mast EE, Weinbaum CM, Fiore AE, Alter MJ, Bell BP, Finelli L, Rodewald LE, Douglas JM, Janssen RS, Ward JW (2006). "A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Part II: Immunization of adults". MMWR. CDC. 55 (RR-16): 1–33, quiz CE1–4. PMID 17159833.

- Wodak, A; Cooney, A (2006). "Do needle syringe programs reduce HIV infection among injecting drug users: A comprehensive review of the international evidence". Subst Use Misuse. 41 (6–7): 777–813. doi:10.1080/10826080600669579. PMID 16809167. S2CID 38282874.

- Jones, L; Pickering, L; Sumnall, H; McVeigh, J; Bellis, MA (2010). "Optimal provision of needle and syringe programmes for injecting drug users: A systematic review". International Journal of Drug Policy. 21 (5): 335–42. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2010.02.001. PMID 20189375.

- Abdul-Quader, AS; Feelemyer, J; Modi, S; Stein, ES; Briceno, A; Semaan, S; Horvath, T; Kennedy, GE; Des Jarlais, DC (2013). "Effectiveness of structural-level needle/syringe programs to reduce HCV and HIV infection among people who inject drugs: A systematic review". AIDS and Behavior. 17 (9): 2878–92. doi:10.1007/s10461-013-0593-y. PMC 6509353. PMID 23975473.

- Verbeek, Jos (2018). "Incidence of sharps injuries in surgical units, a meta-analysis and meta-regression". American Journal of Infection Control. 47 (4): 448–455. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2018.10.003. PMID 30502112. S2CID 54487905.

- Pruss-Ustun, A (2005). "Estimation of the global burden of disease attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among health‐care workers". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 48 (6): 482–490. doi:10.1002/ajim.20230. PMID 16299710.

- Patterson, JM; Novak, CB; Mackinnon, SE; Patterson, GA (1998). "Surgeons' concern and practices of protection against bloodborne pathogens". Annals of Surgery. 228 (2): 266–72. doi:10.1097/00000658-199808000-00017. PMC 1191469. PMID 9712573.

- Anderson JM (2008). "Needle stick injuries: prevention and education key. (Clinical report)". Journal of Controversial Medical Claims. 15: 12.

- "Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act. H.R. 5178" (PDF). 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Tatelbaum, MF (2001). "Needlestick safety and prevention act". Pain Physician. 4 (2): 193–95. PMID 16902692.

- "New Study Quantifies Needlestick Injury Rates for Material RecoveryFacility Workers" (PDF). Environmental Research & Education Foundation. 28 August 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Gold K (2011). "Analysis: The impact of needle, syringe, and lancet disposal in the community". Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 5 (4): 848–50. doi:10.1177/193229681100500404. PMC 3192588. PMID 21880224.

- Macalino GE, Springer KW, Rahman ZS, Vlahov D, Jones TS (1998). "Community-based programs for safe disposal of used needles and syringes". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology. 18 (Supp 1): S111–19. doi:10.1097/00042560-199802001-00019. PMID 9663633.

- MacDonald, M; Law, M; Kaldor, J; Hales, J; Dore, G (2003). "Effectiveness of needle and syringe programmes for preventing HIV transmission". International Journal of Drug Policy. 14 (5–6): 353–57. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.636.9789. doi:10.1016/s0955-3959(03)00133-6.

- "Access to sterile syringes". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 4 May 2015..

- Mittal, María Luisa; Beletsky, Leo; Patiño, Efraín; Abramovitz, Daniela; Rocha, Teresita; Arredondo, Jaime; Bañuelos, Arnulfo; Rangel, Gudelia; Strathdee, Steffanie A. (2016). "Prevalence and correlates of needle-stick injuries among active duty police officers in Tijuana, Mexico". Journal of the International AIDS Society. 19 (4S3): 20874. doi:10.7448/IAS.19.4.20874. ISSN 1758-2652. PMC 4951532. PMID 27435711.

- Thompson, Brenda; Moro, Pedro L.; Hancy, Kattrina; Ortega-Sánchez, Ismael R.; Santos-Preciado, José I.; Franco-Paredes, Carlos; Weniger, Bruce G.; Chen, Robert T. (June 2010). "Needlestick injuries among sanitation workers in Mexico City" (PDF). Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 27 (6): 467–68. doi:10.1590/S1020-49892010000600009. ISSN 1020-4989. PMID 20721448. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Papenburg J, Blais D, Moore D, Al-Hosni M, Laferrière C, Tapiero B, Quach C (2008). "Pediatric injuries from needles discarded in the community: epidemiology and risk of seroconversion". Pediatrics. 122 (2): 487–92. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-0290. PMID 18676535. S2CID 12916388.

- Moore JP (1997). "Coreceptors: implications for HIV pathogenesis and therapy". Science. 276 (5309): 51–52. doi:10.1126/science.276.5309.51. PMID 9122710. S2CID 33262844.

- Bloodborne Infectious Diseases: HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C. (30 September 2016). Retrieved 16 March 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/bbp/disposal.html Archived 25 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Wyatt R, Sodroski J (1998). "The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens". Science. 280 (5371): 1884–88. Bibcode:1998Sci...280.1884W. doi:10.1126/science.280.5371.1884. PMID 9632381.

- Moore D. L. (2008). "Needle stick injuries in the community". Paediatrics and Child Health. 13 (3): 205–10. doi:10.1093/pch/13.3.205. PMC 2529409. PMID 19252702.

- Wyatt JP, Robertson CE, Scobie WG (1994). "Out of hospital needlestick injuries". Arch Dis Child. 70 (3): 245–46. doi:10.1136/adc.70.3.245. PMC 1029753. PMID 8135572.

- "HIV Infection, Risk, Prevention, and Testing Behaviors among Persons Who Inject Drugs – National HIV Behavioral Surveillance: Injection Drug Use, 20 U.S. Cities". HIV Surveillance Special Report 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012.

- Aspinall, EJ; Nambiar, D; Goldberg, DJ; Hickman, M; Weir, A; Van Velzen, E; Palmateer, N; Doyle, JS; Hellard, ME; Hutchinson, SJ (2014). "Are needle and syringe programmes associated with a reduction in HIV transmission among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Int J Epidemiol. 43 (1): 235–48. doi:10.1093/ije/dyt243. PMID 24374889.

- Bramson, J; Des Jarlais, DC; Arasteh, K; Nugent, A; Guardino, V; Feelemyer; Hodel D (2015). "State laws, syringe exchange, and HIV among persons who inject drugs in the United States: History and effectiveness". J Public Health Policy. 36 (2): 212–30. doi:10.1057/jphp.2014.54. PMID 25590514. S2CID 12007017.

External links

- http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-01-60R GAO

- Preventing Needlestick Injuries in Health Care Settings, an alert from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)

- What Every Worker Should Know: How to Protect Yourself From Needlestick Injuries, from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

- NIOSH Bloodborne Infectious Diseases Topic Page

- International Healthcare Worker Safety Center, University of Virginia

- Worker Information https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/bbp/emergnedl.html

- OSHA Bloodborne Pathogen Standard (BBPS)

- Bloodborne Pathogens and Needlestick Prevention, from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)

- OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Workplace Safety Standards and Regulations

- NIOSH Bloodborne Infectious Diseases Topic Page

- OSHA Standard – Bloodborne Pathogens Training for handling BBP

- Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety: Needlestick Injuries